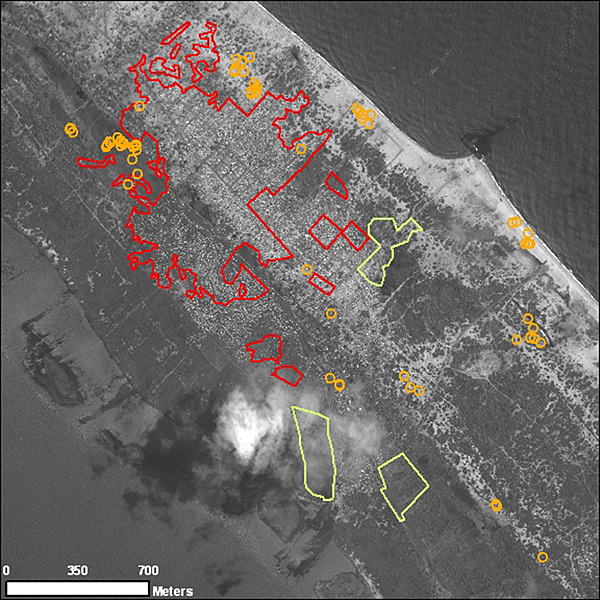

“The most powerful human beings have always inspired architects; the architect has always been under the spell of power,” declares Friedrich Nietzsche in an aphorism to be found in “Twilight of the Idols” and in doing so leaves us in no doubt that he considers it architecture’s purpose to serve the will to power and render it visible. Yet in reality there is more than one form of power, for there are many different facets and variations that differ in their relevance for cities and buildings. Power and violence may be able to manifest themselves in prestigious monumental buildings but they are also discernible in empty spaces, gaps and traces of destruction that mark the urban fabric. Architecture visualizes power and violence in a multitude of ways, whereby it can become an instrument or victim of propaganda, acting as the latter’s silent witness. Bechir Kenzari’s reader “Architecture and Violence” sounds out the various aspects of violence and their effects, be it in images of architecture or the visions and inner world of Surrealist Antonin Artaud. The individual scholarly texts assembled for this ambitious volume were provided by international experts and illustrate the diverse kaleidoscope of the legibility of violence, which is considered here in a brace of different contexts –historical, political and aesthetic. However, meta-levels, as per the definition of that which violence means in relation to architectural theory, have been omitted despite the various interpretations of this concept afforded in the individual essays. As Kenzari suggests in the book’s foreword, it was after the collapse of the bipolar world that the interest in and attention to architectural manifestations of violence emerged as a research focus in its own right within architectural theory, something that also gained considerable relevance after 9/11. In this sense this extensive reader is to be understood as a study placing the individual phenomena within this research field under the microscope. Fascists and Ancient Rome The major fascist propaganda show “Mostra della rivoluzione fascistà”, which from 1932 onwards enjoyed a two-year run in Palazzo delle Esposizioni in Rome, pulled around four million visitors; among them were André Gide and Le Corbusier, who were both unable to conceal their enthusiasm, and raved about the show after their visit. Mario Sironi who was in charge of the exhibition architecture and as an illustrator of fascist propaganda had almost daily contact with Benito Mussolini made full use of a wide range of effects, implementing methods used in film and theater he employed obsessive leitmotifs and emotive compositions. In Rome fascism was presented as a new religion and as an artistic synthesis in the form of photomontages, typographic wall décor and light projections, the likes of which had already been seen in El Lissitzky’s design for the Soviet Union pavilion at the international press exhibition “Pressa” in Cologne. Symbolically-charged rooms seeking a connection to liturgy and Ancient Rome formed key components of a presentation that (very much in the spirit of Walter Benjamin) Libero Andreotti interpreted as the dissolution of boundaries, whereby the rise of mass culture brings art and life face to face. Considered from this perspective, the exhibition provides an example of the aestheticization of politics that Walter Benjamin acutely observed as a symbol of fascism. London’s culture of remembering In one essay, Annette Fierro from University of Pennsylvania, examines the manifestation of violence in London’s cityscape and opts for a very broad take on the subject. Her analysis reaches from the Great Fire of London in 1666, to the destruction caused by German air raids during the War, to the horrific IRA attacks in the 1980s and 1990s. Here she unearths traces of violence in the sense of a culture of remembering, in emotional tendencies that do not permit personal stories to be recounted and are instead focused on commercial interests and profit. One example: The famous “Gherkin”, the glass high-rise belonging to reinsurance company Swiss-Re and designed by Foster and Partners, could only be built at its current site after an IRA bombing had razed the entire plot of land, claiming three lives in process. Nonetheless, today this linkage has for the most part been forgotten and instead the glass high-rise is celebrated as a shining example of green architecture, a hallmark for the international financial district of London. Archigram’s visions for transport of the future also serve as an illustration of the extent to which the past still marks the present. The author considers these concepts as a historico-cultural phenomenon that is closely connected to the role the London tube network played during the War, providing the city’s citizens with protection from bomb raids. According to this particular interpretation of the subject, the relevance of the visions developed by the Archigram group remains inextricably bound up with London’s history and with the tube’s social significance, forged throughout the city’s history, as a place of survival within the system of the big city. From Lebanon to Sudan As much as the philosophical and historical frame of reference varies from one author to the next – the spectrum extending from Georges Bataille to Francesco Borromini and from Theodor Adorno to Rem Koolhaas – the individual essays in this reader prove equally diverse. As a luxury establishment drawing an international crowd built after the end of the civil war, the B018 nightclub in Beirut, which has been saturated with sacred symbols of war by Lebanese architect Bernard Khoury and stands on the site of a former Palestinian refugee camp, serves as a reminder of the concept of violence and death. However, the architecture itself takes these themes to a somewhat esoteric level and ultimately fails to make a distinctive statement. Destruction and loss are also key themes in “From Target to Witness” an essay by Andrew Herscher. Using satellite images, which have been available since 1999 and visualize the destitution of refugee camps, used as proof of a violation of human rights. Projects such as “Eyes on Darfur” by Amnesty International and Google Earth use satellite images to highlight the genocide in Sudan. Nevertheless these images do run the risk of replacing eye-witness accounts, such that architecture or rather its absence is called upon as a witness. Architecture can serve to condone violence, legitimize it or become a specific target of it. However, it also provides those physical structures which aid our survival. Architecture and Violence

Published by Bechir Kenzari

Paperback, 230 pages, English

Barcelona, Actar, 2011

Approx. 24.99 Euro

www.actar-d.com