We are the robots

It is telling that one of the opening exhibits at the Vitra Design Museum’s new show entitled “Hello, Robot: Design Between Human and Machine” is one of the R2-D2 models from the Star Wars film franchise. Telling because it is not in fact a robot at all, but a prop imbued with anthropomorphic features on film thanks only to the help of actors, remote-control operators and liberal sprinklings of CGI fairy dust.

This ambitious and comprehensive exhibition examines the evolution of our ambivalent attitude towards “robots” to date and where that relationship could go in the future. The reality is that the interface between humans and robots has more to do with theatre than with genuine science – even today. “A robot is a theatrical device invented by a Czech playwright”, says cyberpunk author and future expert Bruce Sterling, one of the exhibition advisors. The actual term “robot” comes from the Czech word robota, meaning “forced labour” and was coined by the playwright Karel Čapek in 1920 for his theatre play R.U.R. about robotic workers designed to serve, but which end up destroying mankind. “The origin of robots is exceedingly sinister and we’ve always liked that”, says Sterling. The idea of robots came out of the human imagination and the key element of the narrative that we have created around them – will they hurt us or will they serve us? – is as ancient as the practices of domestication and slavery.

But curator Amelie Klein asks us to take a much broader view of robots. “It’s not about technology, it’s about ideology”, she says. “The popular view is that they should be humanoid in form … they should think and communicate, and move as we do.” But if we accept that robots “do not need enclosed bodies”, that they need only three things (according to Carlo Ratti, Director of MIT’s “Senseable City Lab”): “sensors, intelligence and actuators”, then it also means that “any house, and any environment can be a robot”. From the software bots answering our questions on the Internet to the quasi cyborg extensions that are our smart phones or the systems controlling traffic in cities. “I don’t have a problem with robots”, says Klein, “but I do have one with these enormous networks…whose interests do they represent?”

The first of four sections in exhibition is entitled “Science and Fiction.” It reflects the breadth of popular culture sources that have shaped our familiarity with robots in fantasy, play and film, from the iconic android in Fritz Lang’s “Metropolis” via “Kit” the car from the 1980s TV series “Knight Rider” and 1990s Japanese sci-fi anime Gundam models or Bender from “Futurama” along with examples of vintage toy robots from former Vitra CEO Rolf Fehlbaum’s own private collection. Familiarised, the visitor is then shifted into more unfamiliar territory: that of speculative design. In the 2015 film “Uninvited Guests” by Superflux, imagined smart objects, designed to help an elderly man are in fact policing his every move. Another study called “Ethical Autonomous Vehicles” by Matthieu Cherubini, simulates accidents between humans and driverless cars on the basis of algorithms.

The second section of the exhibition, “Programmed to Work,” looks at our changing relationships with industrial robots. YuMi, designed by the German firm ABB Ltd, is designed to undertake small part assembly work and is fitted with sensors that allow it to work alongside humans. It is, it’s makers claim, “the world’s first, truly safe, collaborative robot”, a breakthrough that takes these incredibly powerful, and potentially dangerous machines, usually surrounded by cages on the factory floor, into the human workplace – working side by side with people.

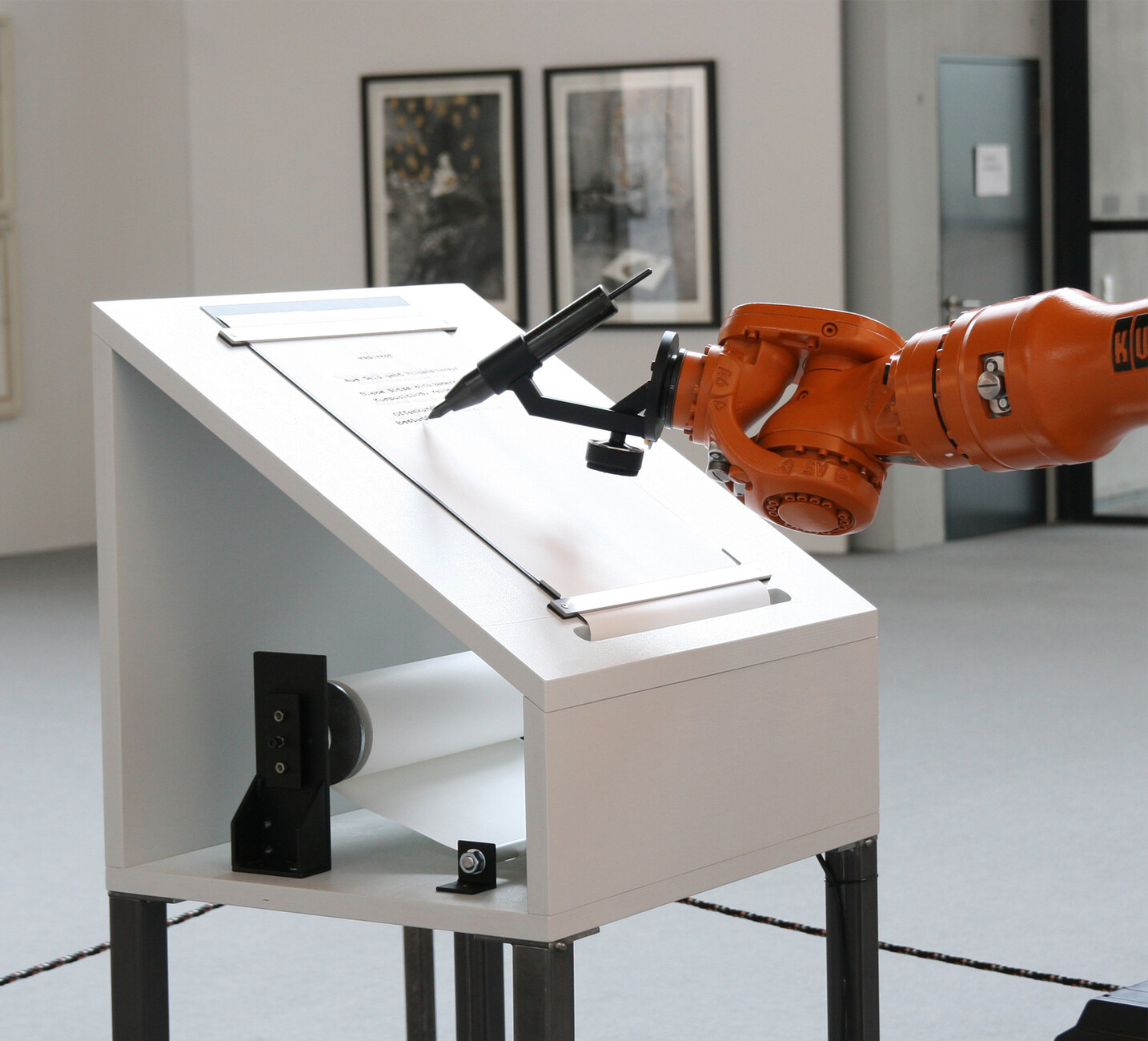

In this section too there are furniture and objects printed by, and in some cases designed by, machines, such as the 3D printed Cantilever Chair by CurVoxels at the Bartlett School of Architecture in London. Another industrial robot in the room, programmed by the German Robotlab, is busy writing out manifestos. These manifestos are randomly generated and make sense, but the robot has no awareness of what they mean – no semantics are involved here. Thus, in the words of ABB CEO Ulrich Speisshofer, who built YuMi: “Human fantasy is still much farther ahead of where reality is”. Although it might appear that the Fourth Industrial Revolution is well advanced, the reality has yet to match the hype. Will robots steal our jobs? “This is a question that has been around since the first industrial revolution”, says Klein, “maybe they will create new kinds of jobs instead.”

In the third section, “Friend and Helper,” we start to touch on the uncanny valley, the place where robots, designed to elicit an emotional response can quickly tip from being cute to creepy. It is about living with robots at an emotional level: robots as carers, as companions, as babysitters and for delivering sensual pleasure. “We need very little to humanise a robot”, says Klein before turning to shout at a little white articulated lamp waving gently around behind her (“Kip”, by Guy Hoffman and Oren Zuckerman), which responds by collapsing into a cowering, shivering heap, eliciting empathic “oooh”s of sympathy from the people in the room. Amazon’s “Alexa,” a physical object for the home that is an Internet interface, is also here. It has voice control and audio recognition to connect the user with the smart home and the Internet of Things.

Here we enter the bigger picture controlled by big companies and it’s a commercial one, but in it we are not the consumers but, as Bruce Stirling calls us: “the livestock”. Film imagery around the room includes scenes from Spike Jonze’s “Her” and Björk and Chris Cumnningham’s “All is Full of Love” contrasted with stills that include a funeral ceremony for pet robot dogs AIBO in Japan, whose discontinuation by Sony in 2014 caused uproar among long-term owners who accused them of killing their pets by refusing to make spare parts for them any more.

For Klein, design is the key to how our relationship with the synthetic develops. It is through design that we can choose, if we wish, to break the dystopian/utopian dialectic we have created around our creations. If the robot designed to trigger emotional responses is fraught with moral issues, thanks to our readiness as a species to anthropomorphise, then the robot designed to enhance or augment our own physical bodies must be an even bigger danger zone.

This is addressed in the final room “Becoming One” housing exhibits including Canadian architect Philip Beesley’s beautiful organic-looking (but essentially just decorative) “Hylozoic Grove” of kinetic coral-like structures and Anouk Wipprecht’s (equally decorative) show-stopper “Spider Dress 2.0.” More science than theatre, though, are the advances in smart prosthetic limbs, and exoskeletons shown here, which allow the paralysed to walk or lend superhuman strength to the wearer. It is interesting that we seem to readily accept and even welcome such cybernetic intrusions – even when it means such devices involve direct implants into our bodies or brains. But the speculative design of synthetic bees (“NewBees”) by Greenpeace, to keep pollination going (and thus the planet alive) in an increasingly real looking near-future scenario where we have managed to wipe out all the living versions, thanks to our own stupidity, again plunges us back into the uncanny zones of creepiness.

It seems that whatever we do, and despite the curator’s best attempts to convince us otherwise, our ambivalent relationship with intelligence of our own design persists and will persist, because it reflects our ambivalent relationship with ourselves. The future is coming and it is of our own making. So it makes sense to start preparing better for it – or at least adjusting our minds to accept the impact.

Exhibition:

Hello, Robot

Vitra Design Museum

Weil am Rhein

until 14 May 2017

Catalogue:

Hello, Robot. Design Between Human and Machine

Ed. by Mateo Kries and Amelie Klein

Vitra Design Museum

ISBN 9783945852101

49,90 Euro