PORTRAIT

Spirited as ever

Vico Magistretti would have turned 100 on October 6: Reason enough for the global design community to celebrate. Yet one hundred years now represents a critical age. Just a few years ago, the magic number still stood for the threshold to a special form of perpetuity. A designer or architect who passed this point without being forgotten almost automatically entered a virtual Design Mount Olympus of sorts. Things have, however, changed since. Sometimes all that lies between the status of design star and oblivion is a single season. This never applied to Magistretti. Nevertheless, it is getting increasingly crowded in the place where the gods and goddesses of design live. Since the 1920s the number of important active players who have left behind a relevant oeuvre in the field of design – including new and rediscovered bodies of work – has increased dramatically.

Vico Magistretti’s work continues to be rediscovered by each new generation. During his lifetime, he taught in Venice, Milan, Vienna and London, training designers who included the likes of Patricia Urquiola, Jasper Morrison and Konstantin Grcic studied under him at the Royal College of Art in London. And right now he is drawing you designers under his spell once again. For example, with his chairs: “I made about 50 chairs in my life,” Vico Magistretti said in retrospect, “of which maybe ten will stick around. But if I hadn’t made all 50, those ten wouldn’t exist either.”

Design theorist Anniina Koivu, who teaches at ECAL University of Art and Design in Lausanne, recently published an analysis of the 300 most important furniture items designed by Vico Magistretti. After all, 70 of them are still on the market – or back on the market. Students of the university also turned a contemporary gaze on some of the furniture items and lamps by staging them for photographs. Most notably however, they traced the fate of 12 iconic designs and researched what led to production of them being discontinued. Sometimes this was due to a large number of imitations flooding the market, other times it was down to the production having become too expensive over time. And in yet other cases, the products had received a great response in the media but were not commercially successful. The analysis drew on sources including the archive of the Fondazione Vico Magistretti in Milan, magazine articles and interviews with companies and their earlier decision makers. While this approach may be exemplary and interesting in terms of design history, it nevertheless doesn’t explain the continuing success of many Magistretti products, which have remained in focus both for manufacturers and buyers. Magistretti’s work is not a matter for obsessive collectors. Rather, his stance is reflected in the practical use value of his objects, and it is this which has allowed them to weather many trends.

There have occasionally been relevant reissues. The chair “Carimate” for example was re-introduced to the market. Inconspicuous at first glance, it is an object typical of Magistretti’s oeuvre. The conceptual quality and longevity of his works often only reveal themselves on closer inspection. This also holds true in the case of “Carimate”, designed in 1960 and the first product to come out of the long-standing collaboration with Cesare and Umberto Cassina. It was created for an early 1960s golf club of the same name, the buildings of which were also designed by Magistretti. Here, the chair with the traditional look, forward-slanted armrests and a seat made of woven raffia provided casual elegance and comfort for a long time. Cesare Cassina discovered the iconic “Carimate”, so it is only fitting that Fritz Hansen is reissuing the chair on the occasion of Cassina’s birthday. Magistretti once noted that regardless of whether they were commercially successful or not, it was those of his designs that “helped a little in writing the history of the company for which I designed them” that he believed were the most important.

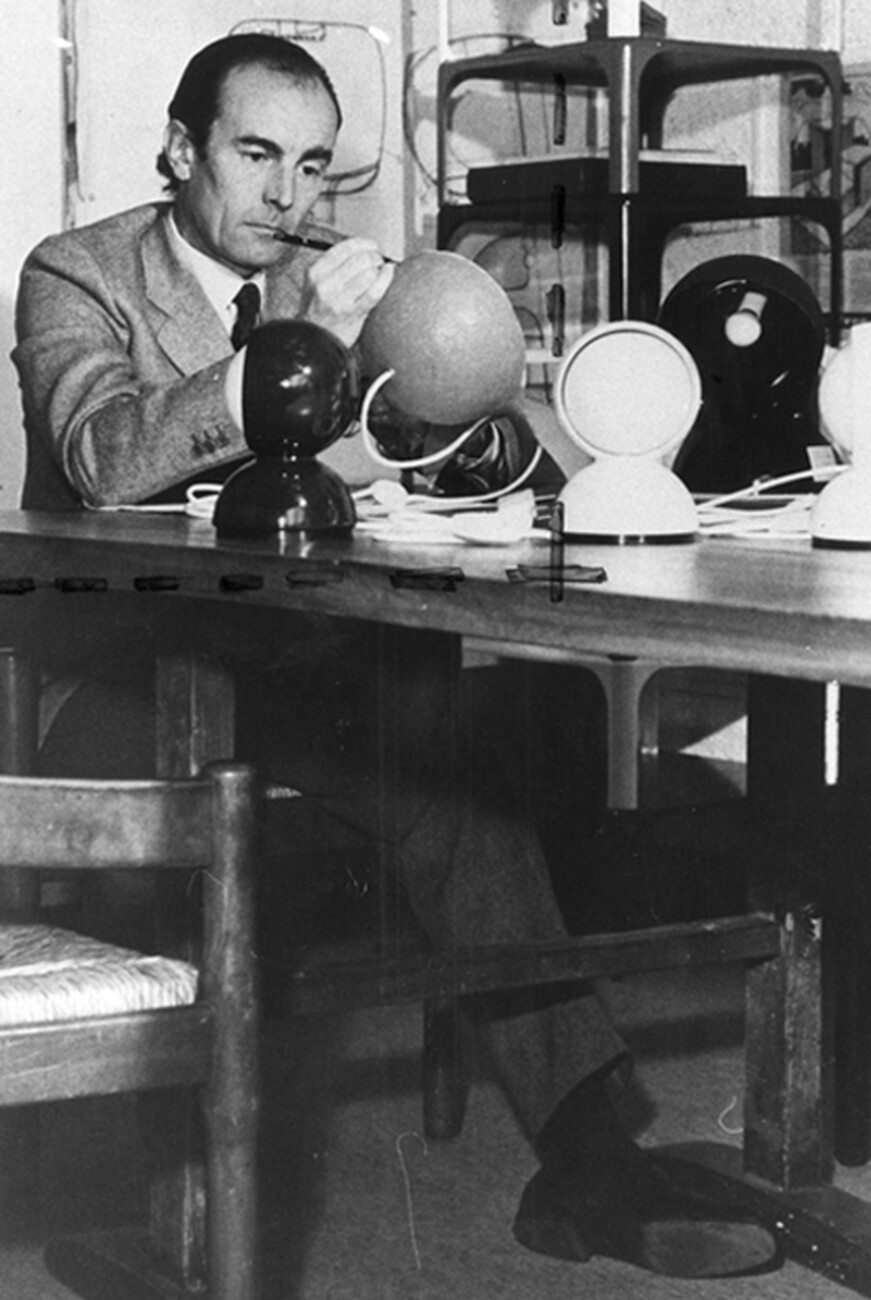

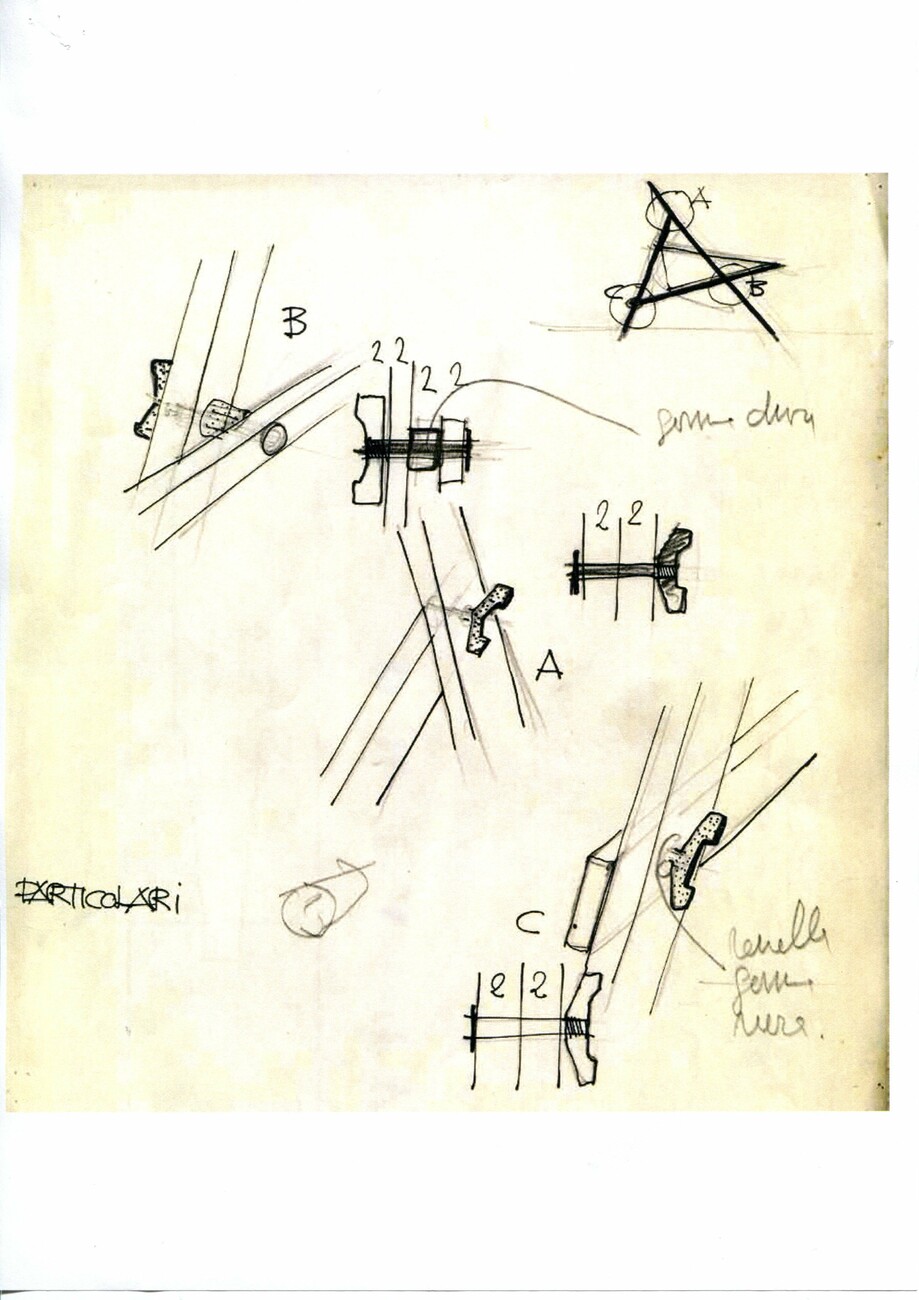

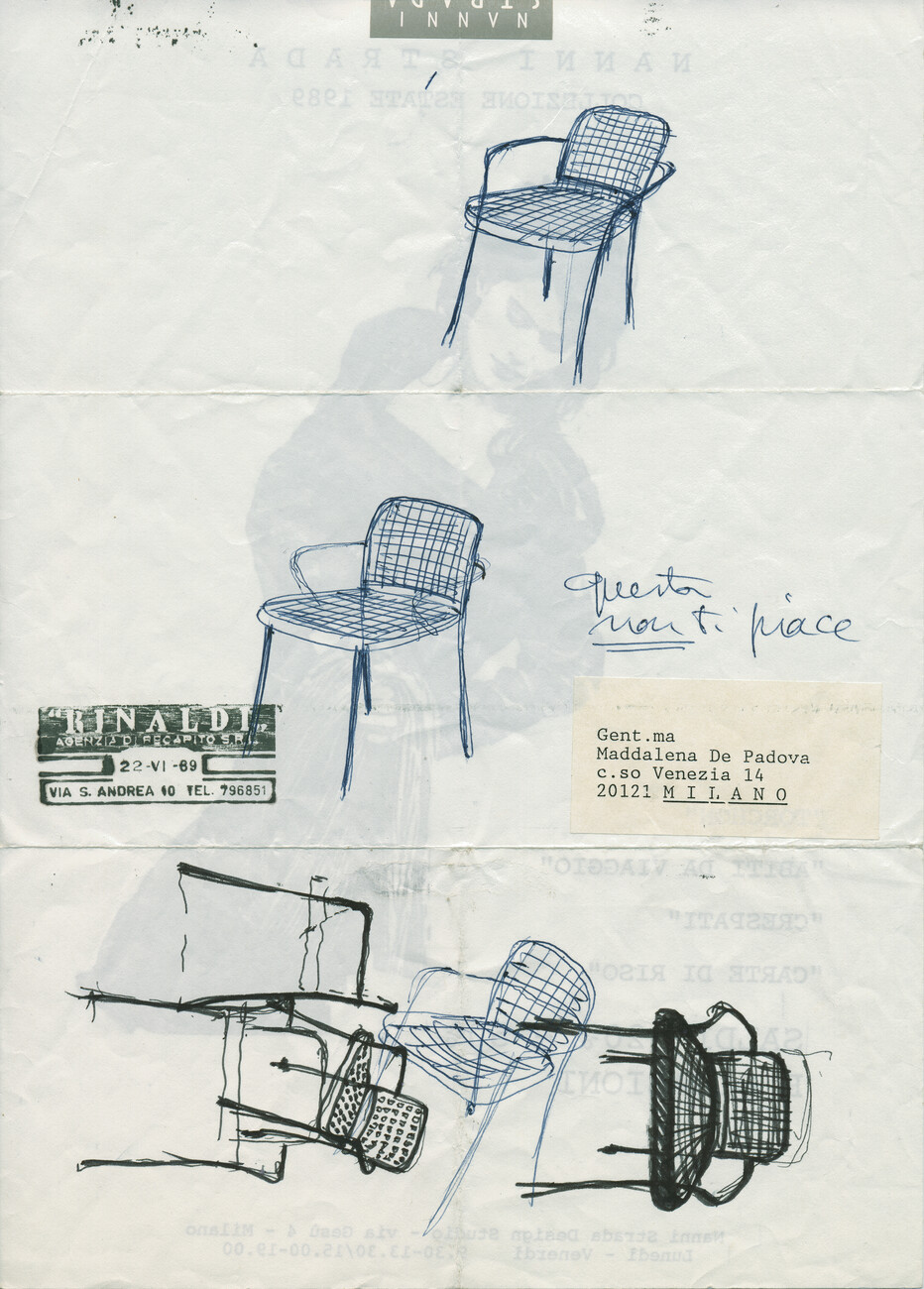

And there were indeed many companies he helped shape: Alongside Cassina, there was the bed manufacturer Flou, the kitchen brand Schiffini, the lighting companies Oluce and Artemide (with the latter also producing the plastic furniture by Magistretti). He occasionally created chair designs with plastic seats for Kartell, and others with wooden seats for Fritz Hansen. Some working relationships turned into close friendships down through the years. For Maddalena De Padova, who made Scandinavian, German and Japanese design famous through her beautiful showroom in Milan, he not only designed furniture, but was acted as a cherished sounding board. Numerous sketches and drawings of his survive. “You won’t like this one” he wrote about a scribble of his “Silver” chair for de Padova, which he sent his client by mail. Maddalena de Padova had asked him to allow himself to be inspired by the classic Thonet chairs. Instead, traditional baskets he discovered on a trip to Japan inspired the solution for the seat and backrest. What he liked even better than sending his ideas by post was to communicate them to the manufacturers by phone. He believed this to be the best way to convey the simplicity of his designs. “I explain things to them in terms of simple shapes – a square, a triangle – and with the measurements.”

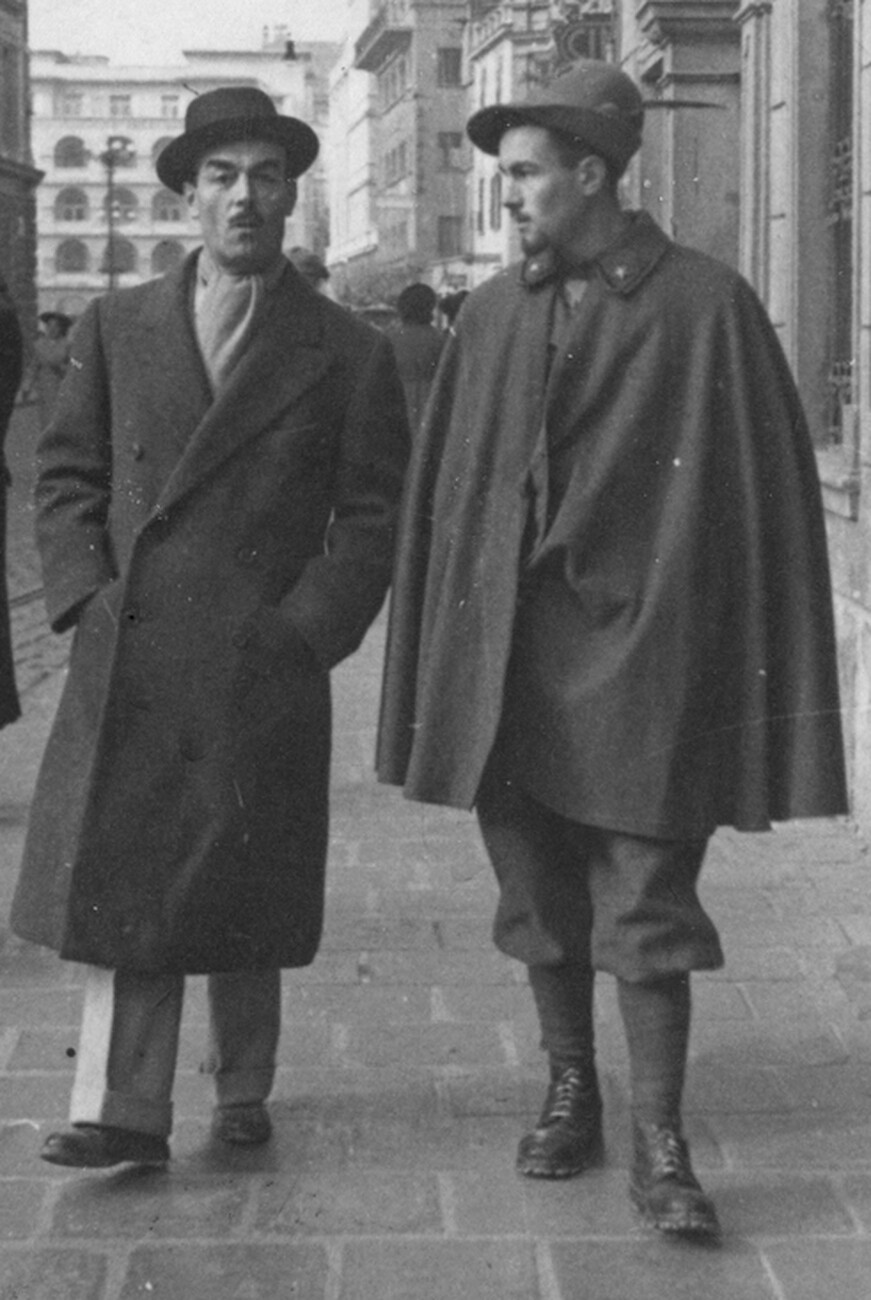

Anyone looking at Magistretti’s work will soon encounter his biography. Born Lodovico Magistretti in Milan, he grew up in an environment on which his grandfather Gaetano Besia (1791–1871) and his father Pier Giulio Magistretti (1891–1945) had left their widely-visible marks as architects. His father was one of the architects of the Palazzo dell’Arengario in Milan, a fascist-cum-Rationalist building on which construction began in 1939, but which was only completed in 1956 after having been damaged in the war. Many of Milan’s architects, including the well-known BBPR group, sought modern forms of expression in the fascist state. After the Allied invasion of Sicily in July 1943, conditions in northern Italy came to a head. The Allies only slowly gained ground, while the German Wehrmacht, security police and fascist gangs persecuted partisans and civilians alike. The introduction of the Italian racial laws in 1939 had forced BBPR co-founder Ernesto Nathan Rogers to flee to Switzerland, where he taught in Geneva and Lausanne. Vico Magistretti, who had begun studying architecture at Milan’s Politecnico in the same year, emigrated to Switzerland in 1943 at the age of 23. It was here that he met Ernesto Rogers, who had then already begun to prepare architecture students for new perspectives in urban development and planning in post-War Italy. Influenced by Rogers and other Modernists, Vico Magistretti completed his studies in Milan in 1945. His father Pier Giulio had recently died, and Vico took charge of the office.

Finding contemporary answers to changing conditions, yet solutions that nevertheless had real staying power, would become Magistretti’s hallmark. His furniture is light and easy to take apart. One of the first items, which he showed as part of an exhibition by the Italian furniture association RIMA in 1946, is now being sold by Campeggi under the name “Piccy”. It is a folding armchair with cloth covers that comes in a range of sunny colors. In 1953, he designed a church with a round footprint, constructed as part of the VIIIth Milan Triennale in the QT8 suburb being built at the time in the northwest of Milan. Housing was on the agenda of the INA reconstruction program when he began working in Milan and the surrounding area after the war. He considered the “Torre al Parco” of 1956, erected opposite the Triennale Palace as a high-rise residential building with cantilevered elements and flexible layouts, to be his first relevant building. The following year he was involved in founding the Italian designers’ association ADI. He observed that there was greater freedom when it came to the design of smaller objects as opposed to that of architecture. He summed this up in 1972 as follows: Designing utilitarian objects allowed for “a different kind of relationship between space and object to be conveyed in the house and in the whole way people lived at home”. Unlike today, with mass industrial production in high volumes increasingly called into question by consumers and a new desire for all forms of artisan craftwork and the applied arts widely taking hold, Magistretti viewed industrial design as “the sole spontaneous and authentic cultural phenomenon” of his time.

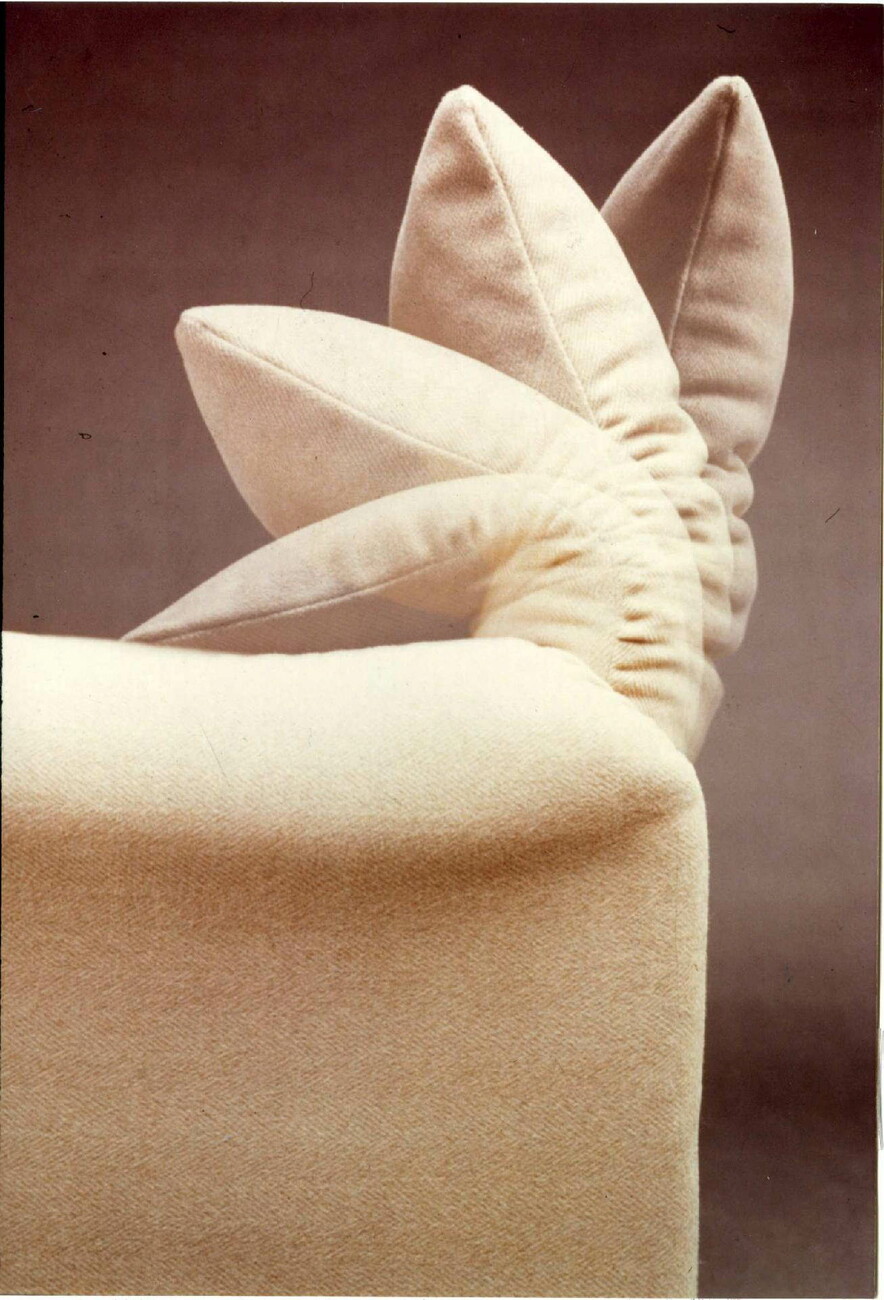

Not just his architecture but also his furniture offered many opportunities for variation. Beginning with the early folding and reclining furniture, objects that change their form in use, and continued in the upholstered items for Cassina, which now featured hidden mechanisms, and above all the repeatedly copied “Maralunga” upholstered furniture range. When arguing with Cesare Cassina about the backrest of the sofa, the latter is said to have gotten physical by punching the point of contention such that the backrest broke. “Great, very good, now it looks perfect to me!” Magistretti exclaimed. This may have represented an extreme when it came to the interaction between client and designer. Yet it also shows the importance of a counterpart willing to take a close look at things and put their ability to persist in real life on an everyday basis to the test. Magistretti appreciated strong partners who knew what they wanted. Unfortunately production has been discontinued of the sofa and armchair “Veranda” (1983) and “Sindbad” (1981), which allude to flying carpets or maybe floating leaves, and were created for societies that had achieved a certain stability, yet also recognized flexibility as a new value.

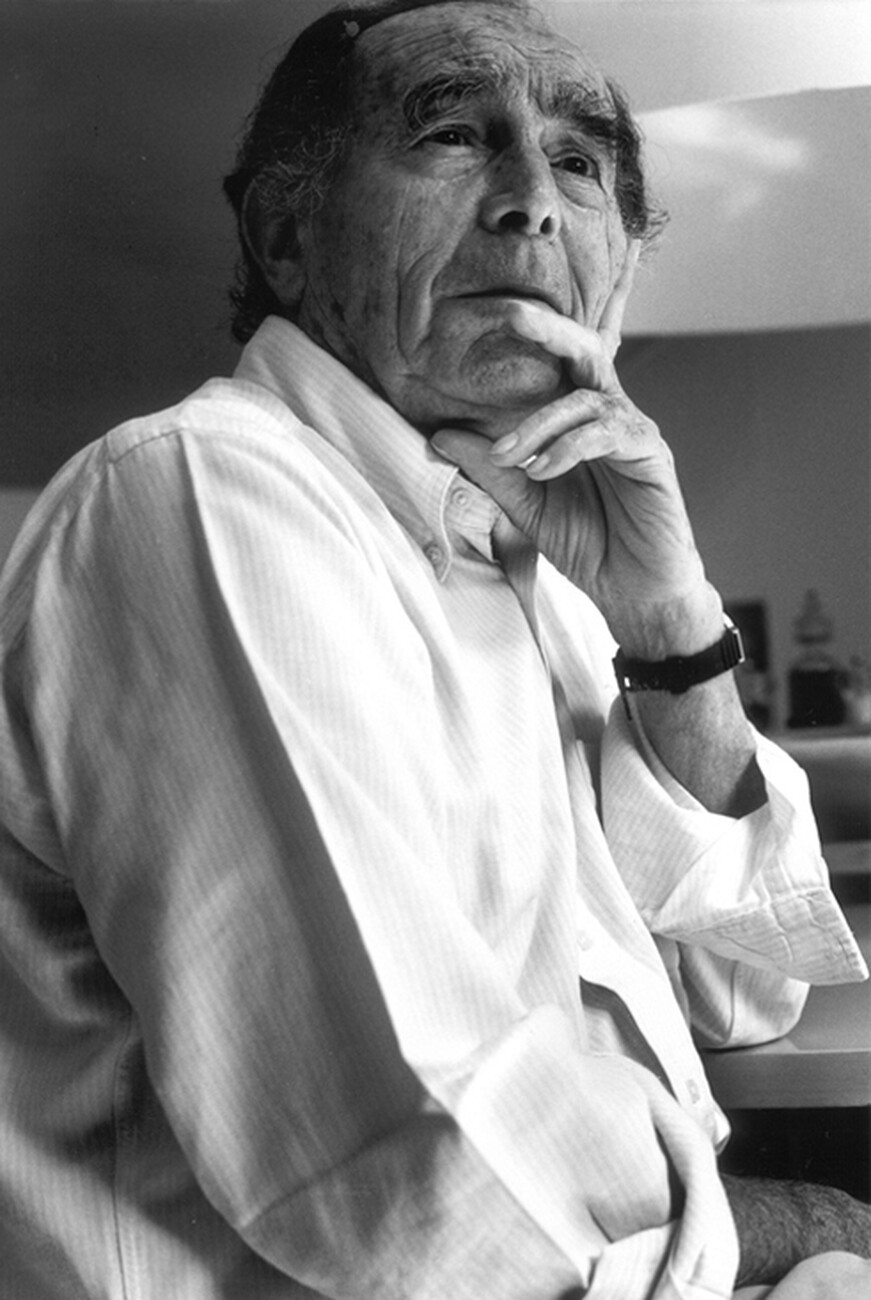

He was not keen on creating variants of the same. He explained this with the simple words “I hate style” in a 2004 interview with Hans Ulrich Obrist for Domus. “The only thing I’m interested in is concept design”. What had impressed him the most in Italian design had been its conceptual simplicity. Vico Magistretti passed away in Milan in 2006. The Fondazione Magistretti began its research work the following year. Founded and managed by Magistretti’s daughter Susanne, the foundation pursues a wise policy, supported by the Milan Triennale and the Artemide, Cassina, De Padova, Flou, Oluce and Schiffini corporatino. Since the beginning of the year large parts of the archive have been made accessible online. Magistretti’s Milan studio was already turned into a museum in 2010. It is open to the public – with restrictions during the Corona pandemic – and conveys a lively impression of the great architect, designer and teacher’s life work. He is a paragon of a time of awakening in design. Even 100 years on, Vico Magistretti remains its spirited ambassador.