Fragments from just now

Troika has created an immersive spatial installation for the MAK in Vienna: The film "Terminal Beach", which gives the installation its title, unfolds a dystopian scenario of the end of natural life on earth and negotiates the interfaces between the virtual and material worlds. Meanwhile, the museum space is populated by 3D-printed "border crossers".

Anna Moldenhauer: What fascinates you about the interaction between analogue and digital realities?

Eva Rucki: We don't think there is a real distinction between these anymore. Virtual reality is a backbone for our environment in a very practically applied way; how things are built and planned, how systems are set up and then manifest themselves in physical networks. Our work is also very much characterised by digital tools. There is a feedback loop between how we see the world using digital tools and machines and how we then build them. It's a two-way exchange. The distinction between the two worlds is becoming increasingly difficult because they are so intertwined.

Conny Freyer: Ultimately, however, they remain different. It's exciting to find out where the differences lie, why we tend to confuse the worlds with each other and what the overlaps are. There are often simulations of reality that influence our daily lives. As technology advances, more and more processes become possible in virtual reality. This also influences our behaviour, both towards each other and towards nature and content that is conveyed through the digital world.

Why did you decide in favour of a dystopia and not a utopia for the "Terminal Beach" project?

Eva Rucki: In view of the current climate scenarios, it's hard for us not to be dystopian. In our film, a robot cuts down the last tree on earth. If you take a closer look at the film, however, you realise that the robot is trapped in an eternal loop. It hacks at the tree again and again, but never manages to bring it down. This suggests that the ending is still open to new paths and your own conclusions. We don't want to make any predictions, but we assume that we are in a time of ecological crisis, which will sooner or later lead to a social crisis. We have already seen the first signs of this.

Would you say that we need to go further into the dystopia to realise what situation we are in?

Conny Freyer: Yes, we have left the age of utopia and are already affected by the real effects of the exploitation of natural resources. You can call that dystopian or realistic.

Eva Rucki: For a long time, new advances, developments and technologies have been sold to us as solutions. These also create new responsibilities. One of the issues we are exploring by designing this creature as a cross between a robot and a primate is also the question of what we want to teach these new forms of artificial intelligence. We want to emphasise the responsibility we have for these new forms of intelligence and consciousness.

Do you currently use AI for your work?

Conny Freyer: That depends on how you define artificial intelligence. I think all of us use AI because it is embedded in many everyday tools today. "Terminal Beach" is a good illustration of how we work. The film explores the same situation from the different points of view of the robot, the drone and the tree. We are interested in these different perspectives and how they can give us an informed and differentiated view of the world. And hopefully also a different way of offering solutions, reactions and interpretations for current tasks. Only when we recognise that we are not outside of nature, that we are a kind of intelligence and that there are other, equally valuable intelligences, do we have the basis to act differently. This also applies to the responsible development of technologies.

You are not only interested in the technology or science itself, but especially in the impact it has on our perception. What methods could help to optimise our perspective?

Eva Rucki: One example: there are various presets for objects, furniture, plants and trees in visualisation systems, so-called "libraries". They offer planners or designers a certain visual lexicon, but this predetermined selection becomes the "status quo" of our collective image database through constant repetition. Many of our actions in life today are conducted in a quasi-covert manner, and we are interested in revealing this through our work. It is about reflecting on our own experiences and being open to learning about developments.

Tell us a bit more about the sculpture group "Grenzgänger", which is part of the Terminal Beach installation.

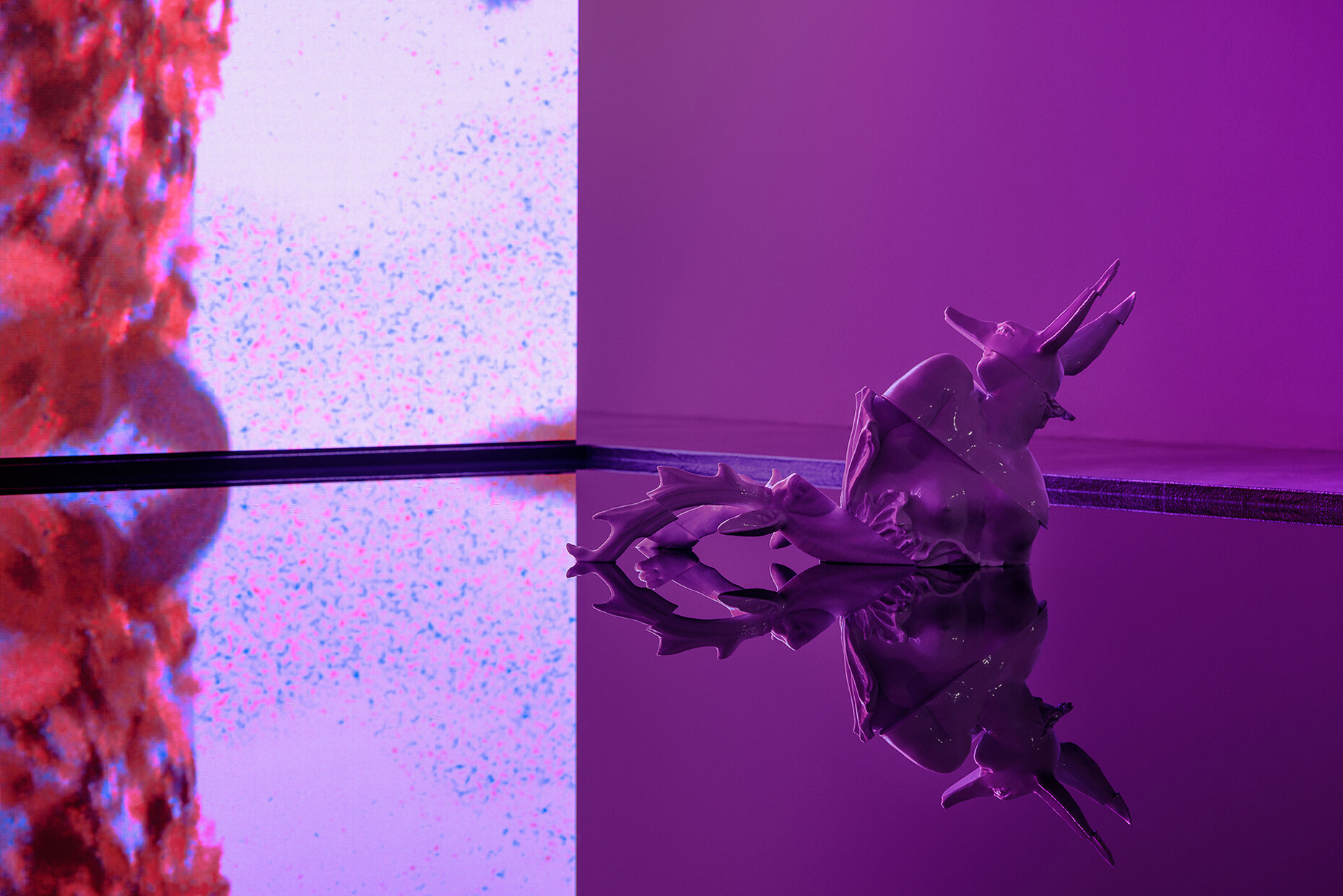

Conny Freyer: The sculpture group at the MAK is a continuation of the series "Compression Loss" (2018), which was followed by a series of works entitled "I woke to find myself scattered across continents" (2023). All deal with the question of where the virtual ends and the physical begins and explore the resulting overlaps. Each group of works has a slightly different focus.

We work with online databases that museums use to make their collections publicly accessible worldwide and have looked at how digital data is stored and what information and material qualities are lost in the process. We were fascinated by the idea of having access to these artworks that are stored in bits and bytes around the globe. Some are stored here, others thousands of kilometres away. Detached from their textures, the digital versions are grey, have a net-like structure, free of colour variety and materiality. They have a second level, so to speak, which is distributed in the digital world on all the world's servers. We found these weightless fragments of mythology and history floating around in the digital world interesting.

Eva Rucki: For our sculptures, we combine fragments of different figures based on the way in which the various data packages that make up the original sculptures are stored on different servers in different corners of the world. This fact also inspired the title of our group of works "I woke to find myself scattered across continents". We then bring these combined fragments back into the real world as a kind of three-dimensional collage. For the sculpture group "Border Crossers", which can be seen in the MAK as part of the installation "Terminal Beach", we have focussed in particular on figures from mythology, folklore and history, to whom the ability to cross borders in the broadest sense is attributed, be it between being awake and the transition into a dream world, life and death, man and animal, man and plant, heaven and the underworld. They are a fascinating breed of historical and folkloric figures who can live in different realms and in different incarnations. We were interested in these kinds of beings as a kind of metaphor for the fact that we are all, in a way, border crossers ourselves, living in both the physical and virtual worlds.

Conny Freyer: That goes hand in hand with the plurality of existence and the plurality of ways of looking at things that we work with. A whole can be many things at the same time.

Part of the sculpture group at the MAK is also a work for which you scanned objects from the museum's collection, fragmented them and reassembled them using 3D printing. What perspective on the MAK would you like to convey to visitors with this transformation?

Eva Rucki: We researched the MAK's in-house digital collection and found some "border crossers". For the new sculpture, we worked with a wax model from the imperial porcelain manufactory and a bronze cast from Japan, a sphinx and a heron. These two objects form the basis for the sculpture 'Heron Sphinx' (2024). The original objects are quite different sizes. In the digital world, however, parameters such as scale, weight and material are smoothed out. The heron has often been understood as a bird that establishes the connection between this world and the hereafter, and the sphinx also bears this duality within itself. In addition, the objects come from completely different belief systems and are geographically as far apart as the MAK's diverse collection extends.

Alongside art, design and architecture are two methods of seeing our world and constructing our daily lives. Do you incorporate these into your work?

Conny Freyer: We work in many different dimensions and formats. Some of the large works are permanent installations. These works are often created site-specifically and have a direct connection to the architectural context. Sometimes we work together with architects, which creates a very practical connection. Extensive research into the history of the site contributes to a conceptual connection. Part of our working process for this type of work is simulation in 3D visualisation software. With certain presettings, you can attach any material to any object at the touch of a button. You can create these perfect worlds without much background knowledge about the nature of a place or object. We find this inherent interchangeability and randomness very fascinating.

Can you explain this a little more?

Conny Freyer: In September 2024, we will open a permanent installation on the grounds of Cambridge University in the UK that is directly influenced by this type of software. For "Third Nature" we have planted fifteen trees – the selection and arrangement of the trees is a three-dimensional interpretation of a tree library used in visualisation software. These virtual tree libraries are quite strange. If you talk to botanists, they would know the Latin names of the plant, where the plant came from, when it might have come to the UK. They have real knowledge of the different tree species. In the database this knowledge is completely lost, the listing is very arbitrary and provides no information on background or cultural meanings. Some have Latin names, others have common names, then there is a "standard tree" that you can create yourself, completely detached from the real world. For this project, we brought one of these digital libraries back into our physical world, but in contrast to the virtual world – where anything is possible – we had to select our trees according to site-specific conditions. To do this, we worked with the Cambridge Botanic Garden, which is part of the university. We were interested in how the virtual and physical worlds are becoming more and more intertwined and how simulations are becoming more and more like our real world. There is a tendency to see these simulations as the world itself, with not only the simulations becoming more like the world, but also the world becoming more like the simulations.

Eva Rucki: While searching through the digitised library collections of the University of Cambridge, we came across architectural and landscape masterplans "for the design of Cambridge" from the 18th century, hand-drawn by landscape architect Lancelot "Capability" Brown. Capability Brown was known for his immense efforts to move mountains, lakes and forests, creating perfect landscapes that conformed to a naturalistic, seemingly untouched aesthetic. What he created was a simulacrum of the seemingly untouched or "naturalised". For all their artificiality, his alterations to entire ecosystems epitomised the idea of an untouched "first nature" that has been so powerful in European Romanticism ever since. 250 years later, the distinction between the synthetic and the organic is becoming increasingly blurred, enabled by technological and scientific advances changing the way we experience our world, and how the boundaries between the natural and the artificial, the real and the romanticised are shifting and constantly being redefined.

This is also due to your interdisciplinary approach.

Eva Rucki: We are very interested in the history of materials and processes because they have a cultural significance for us. We often use these systems to see if we can find a different meaning or use for them. For our large-scale sculpture "Squaring the Circle", for example, we used the method of linear perspective in a way it was never intended to be used. It is not just a tool, but was also used to give things a place in the universe, to create clarity. The work combines various geometric shapes that are visible from two opposing angles and, depending on the direction of view, looks like a circle or a square. Inspired by the everyday phenomenon of people talking about the same thing but having a completely different idea of it, the work unites different perspectives into one whole.

In your work, you reveal the paradox of human nature: We create both living environments that are inspiring for us and ideally promote our talents, as well as undignified, sometimes catastrophic scenarios. Why is this alternation of creation and destruction so fascinating for you?

Conny Freyer: We are fascinated by why and how people develop technology, and the alternation of creation and destruction is a by-product of this. Technological progress is driven by growth, efficiency and economic profit. It doesn't have to be that way, but it's the reason why we end up destroying things, because the profit is often more important than the reason or the way something is developed.

Eva Rucki: The physical distance to the consequences of our actions contributes to an emotional detachment. In the production of computers and smartphones, for example, obsolescence is built in, the so-called planned wear and tear that makes products age faster so that more can be sold. The fact that Western greed for raw materials leads to child labour and civil wars in the countries of origin is very remote for us. This makes it much easier to ignore them. One group of our paintings is based on CCTV footage of hurricanes and forest fires. There is a certain irony in this, because normally CCTV cameras are placed in places to control situations and know what is going on. The fact that these cameras witnessed these events was not intentional. A curator we worked with compared this series of works to Warhol's disaster paintings. I think destruction is a big topic that surrounds us all and is too present not to deal with. We try to approach it a little, but it's actually too big for anyone to deal with.

What are you currently working on?

Conny Freyer: In addition to the permanent artwork "Third Nature" for the University of Cambridge, which will open this summer, we are working towards a large solo exhibition at the Langen Foundation in Neuss, which will bring together many different works. Until mid-June 2024, excerpts from it will also be on display at Galerie Max Goelitz in Berlin under the title "Anima Atman".

TROIKA

Terminal Beach

To 11.8.2024

Museum für angewandte Kunst

Stubenring 5, 1010 Wien, AT

Tip:

Until 26 May 2024, works by Troika can be seen in the group exhibition Poetics of Encryption at KW Institute for Contemporary Art in Berlin.

From the opening on 26 April until 22 June 2024, the solo exhibition anima atman can be seen at max goelitz in Berlin.

The solo exhibition Terminal Beach will be shown at the MAK Vienna until 11 August 2024.

From 1 September 2024, the most extensive solo exhibition to date, PINK NOISE, will open at the Langen Foundation in Neuss.