Onwards to greater things...

What would a city look like in which people not only lived alongside each other, but actually lived together communally? Would this require economic conditions quite unlike those today in the world of globalized capitalism? Must such ideas invariably remain a utopia? And if one wants to foster such a trend, are there past examples one can use, such as the historical cooperative movement? Can a sharing economy lead not only to things being consumed by individuals, but also used by many? What can architecture contribute to a new sense of community? Do we once again need New Man to achieve this? Are new people currently forming or do they already exist?

“Together! The New Architecture of the Collective” is the title of the current exhibition at Vitra Design Museum in Weil am Rhein. Curated by Andreas and Ilka Ruby as well as EM2N, the exhibition focuses on a theme that has repeatedly interested architects, namely change in how we live together between the poles of community and privacy. At least in the Global North there are countless reasons for the fact that collective forms of living together are becoming more frequent: The world of work is becoming more diverse and the division between living and working is increasingly dissolving, not least thanks to new electronic media. Added to which, the Western industrialized nations are seeing a rise in the number of one- or two-person households, with traditional family structures changing (remember: the new demographic) and a growing number of often isolated or even lonely old people. By contrast, in conurbations and mega-cities the striking shortage of affordable housing is worsening by the day, and the loveless new housing being provided obeys solely monofunctional and economic principles and hardly comes up with persuasive solutions.

From the viewpoint of the curators, a “paradigm shift in social values” is currently triggering a “silent revolution.” For this reason, and not just in the title, they put an exclamation mark after the word “Together”: They construe the exhibition as a call to politicians and society to liberate themselves from overly middle-class notions and at long last take the need for alternative forms of housing and living seriously. We have the curators’ enthusiasm for their subject matter to thank for the fact that on balance the sharing economy is viewed through somewhat rose-tinted spectacles and for the rather overly optimistic hypothesis that we are currently experiencing “a return of the collective in architecture, as it were, which spawns innovative and surprising architectural solutions.”

Nevertheless, the wish for a greater collective thrust may indeed drive change and in the vast majority of cases leave urban reality looking pretty miserable by comparison, making the topic compelling at the least. Given that politicians may not per se be so open-minded, I do not wish to decide whether it is so smart to simply ignore, in the euphoria for the purported impending change in mood, that above all among conservatives the notion of community is considered with ambivalence, and to forget the overtones many associate with the word “collective” (Bakunin once introduced it as a substitute for communism).

Be that as it may, the exhibition organizers discern three main trends that they think triggered the “fascinating search for new housing typologies and programs,” namely sharing, demographic change and increasing urbanization.

The ambitious models of collective living in cities such as Amsterdam, Berlin, Copenhagen, Tokyo, Vienna and Zurich, all of which rely on tearing down historical social utopias and residential models, are presented and connected at the heart of the exhibition to form a fictitious model of a city. They seem highly promising, and not just in social terms. They definitely have the potential to spawn residential architecture that is more clearly aligned to user needs. In exemplary manner, a so-called “cluster apartment” of single flats grouped round a communal zone shows what new typologies for ground plans could look like – where one could live together in a community without having to abandon the private sphere of one’s own four walls.

It is also true that architecture which, thanks to the different communal functions it offers, influences the world outside does indeed counter the commercialization of (more or less) public space, or at least encourages such a stance. Where the tears in the social fabric go deeper, and political, social and economic ruptures become all the more evident, alternatives invariably become more attractive: Property can be acquired and managed collectively, costs lowered, social contacts nurtured, and you can even negotiate how exactly you wish to live together. To ensure things don’t get too abstract, different models of cooperation are presented using five projects as case studies: construction group, cooperative, association, private developer, and a hybrid of cooperative and private investment fund.

Siedle organized an Arch+ Feature in the cafeteria next to the Schaudepot on the Vitra Campus which clearly demonstrates that not only ground plans change and that it is no longer workers, but more members of the creative industry that tend to enthuse about such models, and they remain comparatively exclusive. Moderated by Anh-Linh Ngo, editor of Arch+, Pier Vittorio Aureli, co-founder of urban planning office and think tank “Dogma,” and Andreas Ruby discussed the opportunities for an architecture for the collective.

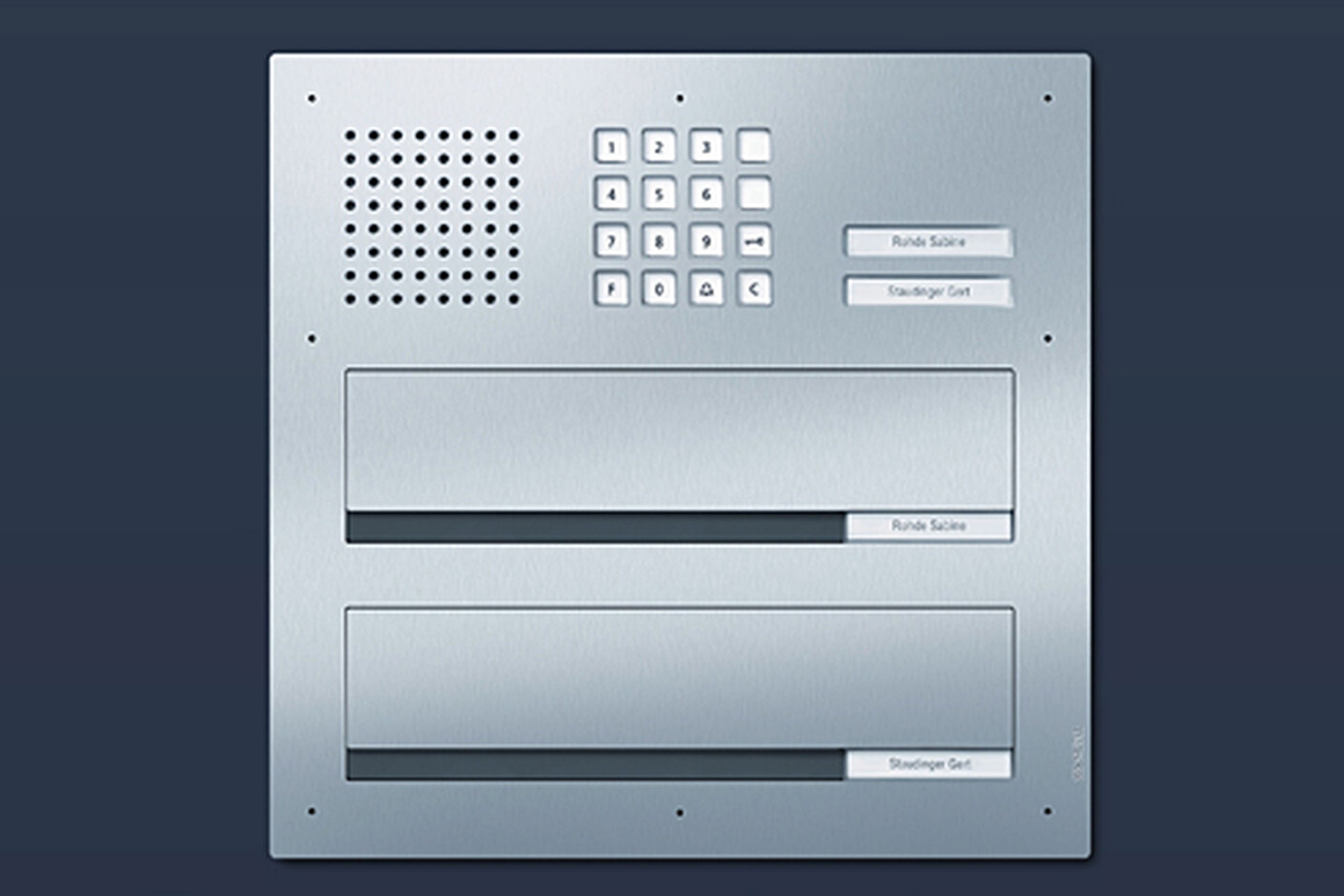

Since Siedle is not only sponsoring the exhibition but has also developed a prototype communication system for collective living, whose novel functions you can test for yourself in the specimen cluster apartment, Peter Strobel, Head of Corporate Communications at Siedle, explains before the discussion proper what the challenges of collective architecture are for a company that focuses in particular on communication at the interface between public and private zones. Strobel outlines the four lessons he learned from the project: First, a system must be simple, which is why, second, it is a virtue not to cram too many functions into such communications concepts. Third, the project shows that technology cannot be a substitute for communication among people, which is why, fourth, such a system should eschew technological complexity as far as possible. Strobel’s conclusion: Siedle learned that projects such as those presented in the exhibition render many things superfluous that everyone otherwise thought were indispensable.

He was followed by Pier Vittorio Aureli presenting the concept for a suburban villa and an urban villa, both developed in 2015 as part of the “Housing Issue” project in Berlin’s “Haus der Kulturen der Welt.” Common to both homes is that they were not designed for a nuclear family, but each for around 50 artists.

Aureli makes it clear that he fundamentally views housing as a place of production and asks why, when building living spaces, a distinction is still made between living and work areas. A house, or so he proposes, produces nothing less than domestic life; its architecture defines the social structure. Here, he resorted to Hannah Arendt’s distinction between “labor” and “work” as regards the basic human activities of working, producing and trading. Labor, such as washing, sleeping, etc. keeps daily life going, he said, but since nothing gets produced in the process it is considered worthless. Unlike the labor required to secure their livelihood, in the domain of work humans then realize their own, permanent world in which they can feel “at home,” he concluded.

Aureli not only asked: Why do we live in houses? Why do their ground plans not foresee communal rooms? Why do houses cut themselves off to such a degree? Why is the family considered a microcosm that exists separate from all others? He also described how, by taking a villa as the quintessence of a “domestic space,” an attempt was made to devise an alternative residential model. A key role was played here by the following criteria, with Aureli saying they were more important than the actual project: a financing model that ensures the properties are not part of the housing market and speculation; locations that are not relevant for other project developments; a structure tried and tested by industrial construction and thus guaranteeing low costs; minimum, optimized individual rooms, and maximum, flexible collective areas. An artist’s studio served as the role model here, as there the distinction between “labor” and “work” no longer applied.

The subsequent discussion swiftly led to the question whether we all had to become artists to solve the problems of collective living. Aureli’s answer was not entirely persuasive. Artistic production, he said, has since the Renaissance been paradigmatic, as artists have for some time “chiseled away” under conditions that now apply for many people. If this is the case, then in the current age of chiselers there’s evidently a need for new forms of living and collective living.

Exhibition:

Together! The New Architecture of the Collective

Vitra Design Museum, Weil am Rhein,

Through September 10, 2017

Mon. – Sun. 10 a.m. – 6 p.m.

Catalog:

Together! The New Architecture of the CollectiveIlka & Andreas Ruby, Mateo Kries, Mathias Müller, Daniel Niggli (eds.)

Photographs Daniel Burchard

German and English editions

352 pages, paperback, approx. 443 illustrations

Ruby Press Berlin EUR 49.90