Three questions to Peter Cachola Schmal

Anna Moldenhauer: Utopia or dystopia – what is your impression of how we will live together in the future according to the contributions to the Architecture Biennale 2021?

Peter Cachola Schmal: Mixed response. Dystopia still predominates, and by that I also mean very serious studies commissioned by the European Space Agency to SOM Architects on the construction and operation of a moon base. Realistic, but of course cruel. Some of the esoteric, some of the imaginative, and much of the overly cerebral and textually convoluted came especially from the elite American universities. This part in the Giardini Biennale pavilion was hard to sit through. Beautiful and very sensual, fragrant is the ring of tall tree trunks by Elemental Architects at the Arsenale water basin, which is to serve as a meeting place for the Chileans and the indigenous peoples of their region and is based on earlier examples.

Which contribution has particularly stuck in your memory?

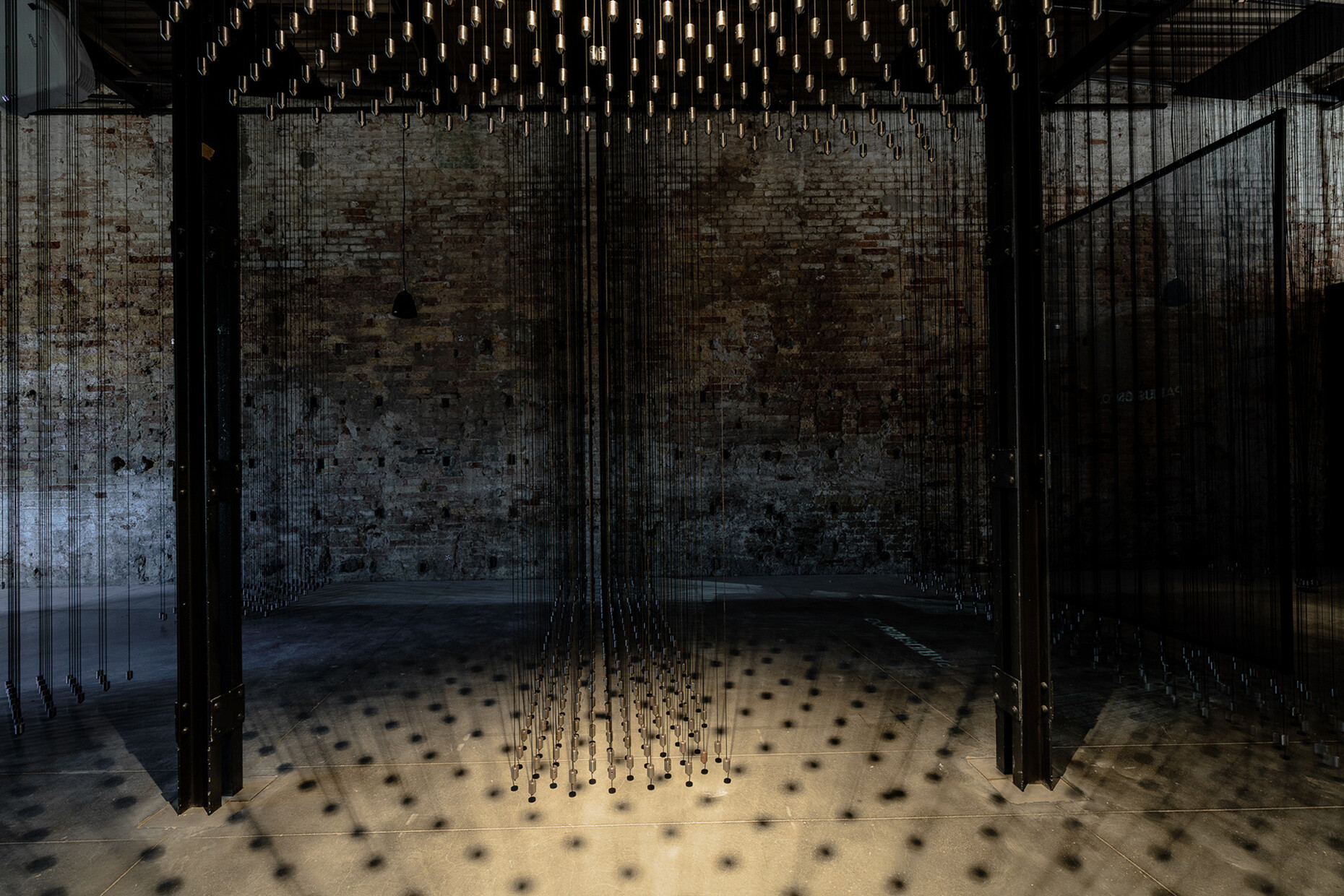

Peter Cachola Schmal: Architecturally, there was very little on offer, which was probably due to the theme and the curator. A great discovery for many could be the Lebanese-French architect Lina Ghotmeh and her brutalist residential tower in the port of Beirut, the interior of which was destroyed by the infamous explosion shortly after completion. Which didn't matter to the sculptural building. I also liked the Russian pavilion in the Giardini, which former OMA partner Ippolito Pestellini Laparelli had renovated in a way that was liberating. The original spatial references to the neighbours, the lagoon and the surrounding nature were reinstated in the building, which had often appeared gloomy in the past. Windows and doors were glazed and made permeable to views as well as light. All are said to have existed before, but were covered up for many years. The basement has been added to the exhibition space and overall a true masterpiece by architect Alexey Shusev from 1914 has reappeared.

The contributions go beyond the topic of architecture and also critically question our development as a society – as in the German contribution as a retrospective from the year 2038. In your opinion, what is the task facing architects in this transition phase?

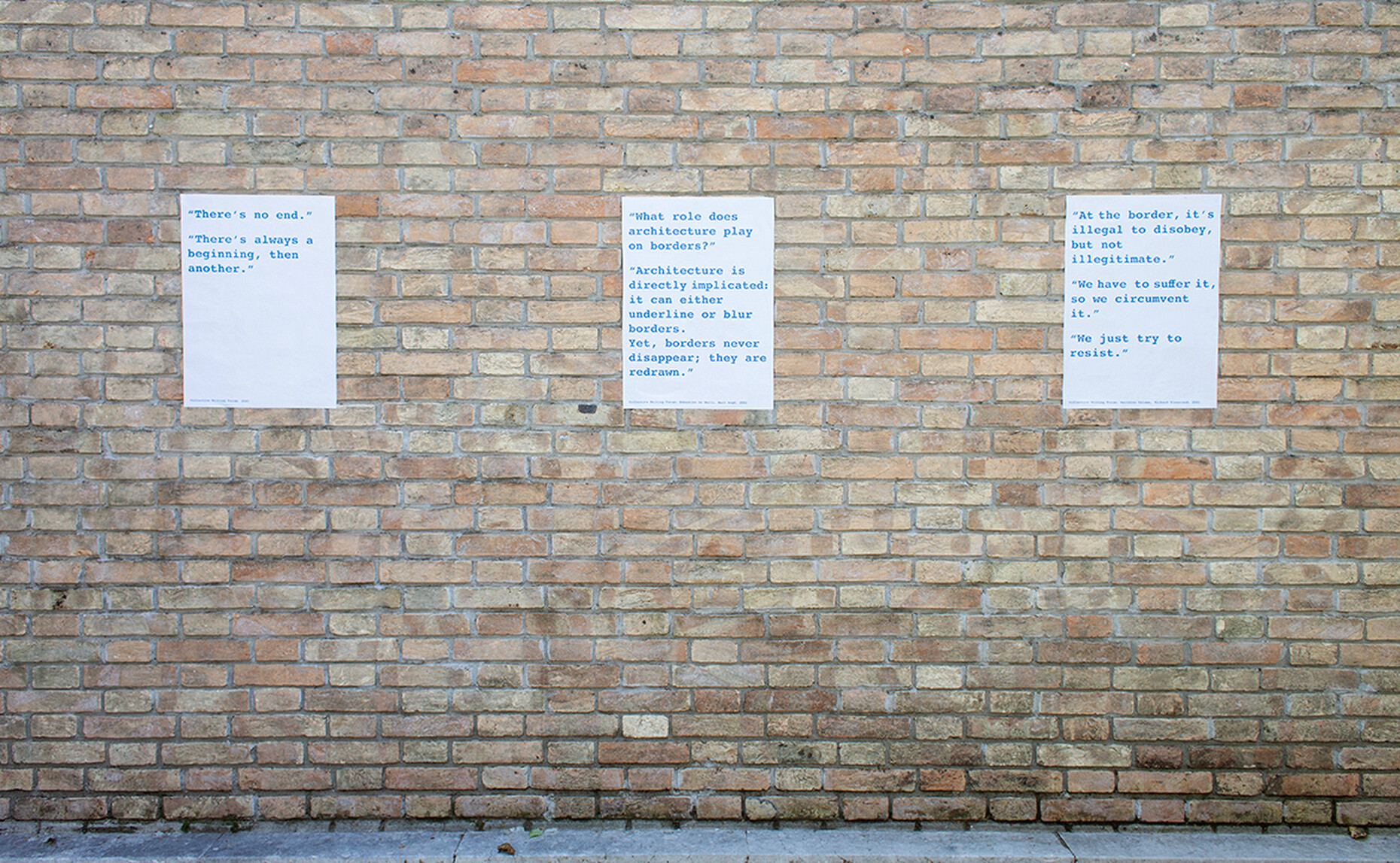

Peter Cachola Schmal: The German contribution did not only generate sympathy in its radical rejection of the physical exhibition (by printing QR codes on the walls in the empty pavilion). The international press was relatively offended. The uproar over this gesture naturally obscured the view of the cinematic work and the fundamentally optimistic attitude behind the 2038 project. Which was also the reason for us as a jury to select this entry. Of course we would like to hear how things have gone well in the future, and how we have all saved the world of tomorrow. When this Corona pandemic will finally have passed, urgent problems will become clearer, such as climate change and the necessary reduction of CO2 emissions. This is the big task for our industry, which, with construction, makes a major contribution to the high CO2 consumption. Who will invent substitutes for energy-intensive cement, new construction methods and materials, ways of urban densification and for affordable housing without getting into major conflicts with the preservation of nature? Who will tackle the transformation of our cities, our energy, our mobility, our behaviour? While the world population continues to grow - because all those who are under 18 today will need a built environment to live and work in. There are about three billion of them, as many as lived on the earth in total in 1960. All the infrastructure that people had then will be needed in addition! That is an unimaginable amount of work for architects and engineers – and does not mean shrinkage, but enormous growth for the future!