At this year’s Venice Architecture Biennale Rem Koolhaas presented the construction history of the last century as a process of ever increasing banality. His “Elements of Architecture” exhibition showed how an open design philosophy that experimentally cast traditional construction methods and forms of ornamentation into doubt, morphed into a prevailing current that no longer allows alternatives above all for economic but also ideological considerations. With a wealth of material, the exhibition builds around hypotheses and is in part manipulative in the way it sheds light on the fraught relationship between Modernism’s promises and what has gained sway as the standard in terms of industrialization and globalization.

Just how and when in this process the epigones replaced the imaginative inventors was left blurred in Venice. Just as why the one or other experimental inventor turned from being a pioneer of a new idea into an executor of “construction industry functionalism”. This was the term coined by founding director of Deutsches Architekturmuseum Heinrich Klotz to describe a Modernist practice that signed its peace with minimal programs and did not bother itself with thought-through designs or deeper questions as to the meaning of architecture.

Not a pleasant present

In construction activity in the early 21st century the past is wallpapered over with compound heat insulation panels. New builds pay homage to a “Bauhaus Style” that never actually existed in that form. Existing historical buildings, be they listed or not, are put up for grabs. If at all, they get reduced to frontages worthy of preservation. The maximum purpose to be attained by a building is its conversion into a covered shopping mall. The revisited city of today increasingly consists of built zombies bereft of a history, a present and a future.

Baldly placed alongside this construction practice is the memory business which has been delegated to the museums and media. Architecture exhibitions show us what Modernism could have achieved. And what architects and designers perhaps still could do if we were to stop condemning them to dressing up banal investor designs in as a spectacular a garb as possible.

For example, an exhibition at Marta Herford reminds us of Heinz and Bodo Rasch, two unusual pioneers of the New Building movement, whose imaginativeness had a universalist thrust. The brothers termed the reach of their joint company that operated in Stuttgart from 1926 to 1930 “Civil Construction, Furniture Building, Advertising Structures”. They blended flexibility with tenacity.

Humiliated forever

Prior to setting up the company Heinz Rasch (1902 to 1996) studied Architecture at the technical colleges in Hanover and Stuttgart. He wanted to complete his studies under Paul Bonatz, who masterminded the design of the Stuttgart Main Railway Station, which was then under construction. With one study project Heinz Rasch initially found himself placed under the tutelage of another Stuttgart lecturer, Paul Schmitthenner. Rasch had proposed a “zestful arch on the hill for his idea of a villa on a slope”. It was an early example of organic architecture which Schmitthenner strongly disliked, accusing Rasch of having an “unfocused mind”. In an autobiographical piece written in 1990 Rasch points out that this public humiliation in college was “subconsciously present in all my designs” through his life. An awful notion.

This and other episodes from the life and works of the two designers are outlined and structured by Annette Ludwig in her precise and intelligent monograph on the “Architekten Brüder Heinz und Bodo Rasch” which came out in 2009. She documents how Heinz Rasch wrote almost daily to his girlfriend and later wife Jutta Kochanowski about life and work between 1926 and 1930, to which he added photos and small drawings. The correspondence also describes various successes and events such as the visit of Mies van der Rohe, who fleshed out plans for the Weissenhof Estate in Rasch’s office, not to mention reports on setbacks and economic difficulties.

Bodo Rasch (1903 to 1995) initially graduated as an agricultural engineer. During that time he trained and worked for various cabinetmakers acquiring a knowledge of furniture design and manufacture. From 1923 onwards he developed crafts objects, and from 1924 he designed chairs. During this period Heinz and Bodo sporadically collaborated. “Werkkunst Arche” and “Deutsche WA-Möbel-Gesellschaft” were the names of their first start-ups, both of which they swiftly abandoned. Heinz Rasch intended to set up a studio for “interior design” with his friend, the painter Willi Baumeister. Instead he ran the press desk for the 1924 “German Building Show” in Stuttgart, Baumeister designed the relevant newspaper. There and in Berlin, where he worked from April to October 1925 as an editor of the BDA journal “Die Baugilde”, Heinz Rasch came into contact with architects and artists who were members of the international avant-garde, among them Peter Behrens, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Mart Stam, for example. Working from studios in a series of apartments in Stuttgart through the summer of 1930 the Rasch brothers pursued their joint project on the “reproduction”, i.e., serial repetition of furniture, buildings, and typographical design.

Concentrated time

In the just under five years they spent working and designing things together, their construction studio concerned itself with “exhibition and advertising edifices” (mainly with the design of trade-fair booth), “built a detached home and published five books” as Bodo Rasch later tersely summarized the period. In 1927, the duo designed the house for their uncle in Bad Oeynhausen. “The wish for honest buildings means that the content of a house must converge with its appearance,” stated Heinz Rasch. The villa for Ernst Rasch consists of inter-penetrating brick cubes of different heights. Not least because the developer was a scion of a local brickmaking family. Later owners “distorted the building by making countless changes to it,” writes Annette Ludwig. Among other things, for this reason it now resembles a white Bauhaus cube.

Explained using their own examples

So what about the five books? Like so much as regards the Raschs, there is no simple account. Their book on “Wie Bauen?” came out in three different editions, whereby the first two vary more strongly in terms of content, while the third differs from the second only by the imprinted red numeral for the year, “1929”. “Wie Bauen?” first came out in 1927 in the context of the construction and interior design for the Werkbund estate at Weissenhof in Stuttgart. With a horizontal spine, the volume is more than just a superficial guide to the exhibition. It conveys the various approaches to building in an entertaining and vivid way, initially distinguishing masonry from skeleton structures. Alongside details on the furnishings and construction of the individual edifices on the Weissenhof estate, countless ad clients presented details of the benefits of their products, from the building materials through to the hot-water supply system. The Raschs repeatedly and unabashedly inserted their own projects in-between in the overall setting of the book.

For example, here for the first time they present their most important visionary project, the idea of suspended houses. Moreover, the furnishings the Raschs designed for Mies van der Rohe’s and Behrens’ Weissenhof houses are to be found in their publications. In 1928 an amended, less ad-heavy version came out, devoted to “materials and structures for industrial manufacturing”. That same year, they wrote and designed “Der Stuhl”, just under 60 pages and reprinted in 1992 by Vitra Design Museum. In it, Heinz and Bodo Rasch (contrary to alphabetical order, the name of the older of the two always appeared first) outlined the transition from crafts to industrial production of furniture and using examples of how they developed their own furniture and also designs by Mart Stam and Mies van der Rohe they described how the structure of furniture changed owing to new production methods and uses.

In 1930 they published their systematic work on “Zu – Offen”, which provided an overview of contemporary product types for doors and windows. “Gefesselter Blick” was the name of their next volume, containing 25 brief monographic texts on selected ad designers, from Willi Baumeister through Max Bill, Walter Dexel, John Heartfield, El Lissitzky, Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, Kurt Schwitters, Mart Stam, and Jan Tchichold to Piet Zwart. Here, too, the makers and designers Heinz and Bodo Rasch included themselves, with programmatic statements and it is only right that their names appear alongside those of designers who today are far better known.

Heinz and Bodo Rasch came to blows over issues of copyright and stopped working together. The reasons were not only the impact of the Great Depression but also changed life circumstances (both had married, Heinz in 1930, Bodo in 1931). They went their separate ways, only on occasion communicating by letter. Some of their designs, for example on the innovative suspended houses, were included in the collections of the Canadian Center for Architecture in Toronto, the MoMA in New York and Deutsches Architekturmuseum in Frankfurt, who have all loaned works to the Herford show.

Separate Strategies

After going their separate ways, the two architects both created an impressive range of works, often, however, with smaller projects that have gone less noticed by architectural historians. Bodo Rasch can be considered to have initiated the Kochenhof Estate in Stuttgart. Instead of the imaginative wooden structures he had proposed (there’s a model in the exhibition and the surviving original plan), banal houses in some purportedly local idiom were built. Heinz Rasch relocated to Wuppertal where he worked with entrepreneur Kurt Herberts, for whose paint factory he drafted new buildings and was in charge of advertising. Herberts, who had protected over 30 politically persecuted persons from the Gestapo by keeping them inside his factory, created a paints lab for which Heinz Rasch engaged the services of his painter friends from Stuttgart, Willi Baumeister and Oskar Schlemmer as scientists. In this way, the as good as outlawed artists and their families managed to keep their heads above water for a while. The exhibition includes some smaller, very personal pictures by Schlemmer and Baumeister that once belonged to the Rasch brothers.

In Döppersberg in Wuppertal, where once Oskar Schlemmer and Heinz Rasch lived and conducted research, the post-War city is currently being upended; streets are being relocated, and shopping malls built. Much to the annoyance of critical locals, who associate exaggerated public construction projects with sharp cuts in municipal services.

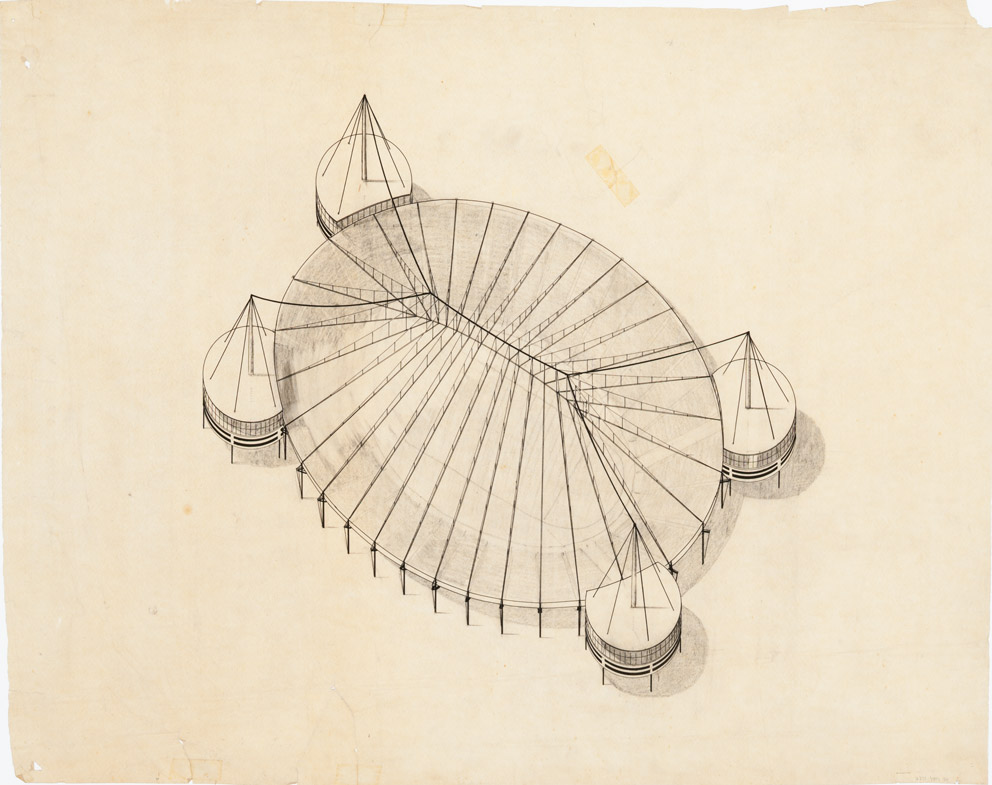

Many of the designs that were especially close to the hearts of Heinz and Bodo Rasch remained on the drawing board. When, for example, Stadtsparkasse Wuppertal finally resolved to erect their head office as a suspended building, the project was not realized by Heinz Rasch, but by Paul Schneider-Esleben. From the 1950s onwards, Heinz started anew, patenting new ideas for suspended houses, while Bodo opted to construct railway station and track superstructures Stuttgart (so-called “large relays”). Bodo developed artificial “mechanical clouds” using pneumatic elements as well as container-shaped structures. Most of the efforts did not get beyond the planning stage or publications. When, in 1967, the journal “Bauen+Wohnen” once again presented the 40-year-old visions of suspended structures and cable-based superstructures for stadiums, housing, and swimming baths, this happened at a time when a new avant-garde was in full swing and was logically titled “Realized Utopia”.

Museum stimuli

It is worth taking some time for the exhibition at Marta Herford. Heinz Rasch’s personal image assemblages, the designs, plans, typographic works, models and furniture prototypes all bear careful inspection in order to grasp their importance. One needs also distinguish between areas where Heinz and Bodo Rasch stimulated the furniture avant-garde (e.g., with their “Sitzgeiststuhl” or the “WA-Normalstuhl”, intended for mass production) and those where they were contemporaries of the development of what they called the “protruding chairs” of Stam and Mies. Vivid materials were provided on loan by Tecta’s Axel Bruchhäuser, who discussed things intensively with Heinz Rasch and made small series of his tubular steel chair, patented in 1974.

The exhibition does not set out to offer an extensive exploratory account of all aspects of the life and works of the Rasch brothers, as the museum seeks to create stimuli, as director Roland Nachtigäller says. Prime examples of this are the collaboration with external curators, such as Bern’s Klaus Leuschel, who as an expert on design and architecture forges links between the Rasch brothers and the avant-garde of the 1960s not to mention contemporary projects. Sadly, various realized buildings, such as the Nakagin Capsule Tower by Kisho Kurokawa have become neglected or risk demolition.

As if all of this were not in itself enough, the museum juxtaposes old and more recent visions with contemporary artistic objects. Whereby unfortunately this time, and unlike in the previous show on Buckminster Fuller, it seems more like a matter of random additions. The exhibition architecture is also annoying. It doesn’t help visitors, is not an element in its own right, but a material overkill in copper and plastic, with folded sheet metal that attests to a good lack of knowledge, as it runs counter to the intentions of the works on display here. The book title “Gefesselter Blick”, the captivated gaze, which referred to the methodology of advertising at the time, was taken as the basis for the Marta exhibition title, “Entfesselten Blick”, the unfettered gaze. Why is anyone’s guess. Just as is why projects that were joint ventures are now assigned to individual designers. Perhaps the catalog, which comes out in November, will offer some clues? But on the whole these are incidental shortcomings, given the wealth of projects and ideas by the engineers-cu-designers Heinz and Bodo Rasch, presented here for the first time in such a comprehensive range. So head for Herford!

“Der entfesselte Blick. Die Brüder Rasch und ihre Impulse für die moderne Architektur”

Marta Herford, thru Feb. 1, 2015

www.marta-herford.de

For more details:

Mart Herforde (ed.), Der entfesselte Blick / The Unfettered Gaze

Die Brüder Rasch und ihre Impulse für die moderne Architektur

(Wasmuth: Tübingen & Berlin, 2014), EUR 39.80

Annette Ludwig, Die Architekten, Brüder Heinz und Bodo Rasch

Ein Beitrag zur Architekturgeschichte der zwanziger Jahre,

(Wasmuth: Tübingen & Berlin, 2009), EUR 49.90

Heinz and Bodo Rasch (eds.), Gefesselter Blick

25 short monographs and essays on new advertising

1930, Reprinted 1996

Lars Müller Publishers, Baden (Switzerland), 1996, EUR 45