Today, his very name is associated with an agenda. Everyone gets excited when the word gets round that Konstantin Grcic is to hold a new show. He has never been content to simply place objects on plinths in a museum. And this time he has evidently once again decided that merely staging another overview of KGID products was not enough, even if in recent years he has added any number of new designs that could be termed ‘typically Grcic’ to his list of works, which dates back to 1986. Although it is often not easy to define exactly what counts as typical of his design output. Needless to say, at the Vitra Design Museum in Weil am Rhein you will again see any number of Grcic’s iconic designs, be it as studies, prototypes or the finished article.

They’re all there, nothing’s missing – “Mayday” and “OK”, “Pallas” and “Chair One”, “Pro” and “Medici”. “Bishop” meets “Tom Tom & Tam Tam”, “Square” meets “Chaos”, “Miura” meets “Landen”. Even the very latest additions are on view, in the form of the transparent furniture in the “Man Machine” series and the “Artek Chair” desk chair. Yet even if almost everything that greets the eye was created by Konstantin Grcic, “Panorama” is not some common-or-garden design exhibition. However, if the exhibition is not simply a parade of chairs, tables, armchairs, recliners and luminaires, then what is it?

The special appeal here is no doubt that Grcic offers us not just finished products and studies, in other words some object or other, but instead sheds light on the various contexts in which they were produced and are used, and shows how these can be influenced.

Grcic serves up four different perspectives on the present, past and future of life, how it changed and how it can be designed: as “Life Space”, “Work Space”, “Public Space”, and “Object Space”. This is rounded out by wall panels that explain his respective view of the section in question and provide a wealth of background information. All in all, in the various installations he audaciously offers nothing less than a set of forecasts on the immediate future.

Grcic courageously takes the plunge straight into rooms that not only have various functions but reveal different conditions, influences, dependencies and contexts. He transports us into spheres in which things no longer appear in isolation and captures their characteristics in narrative webs and fictitious scenarios. He takes his work and his style of life as a designer surprisingly literally, shows what designing means to him, and presents specimen samples of this. Without any touch of the visionary, precise and clear, as modest as always and free of any allures, Grcic outlines how those spaces (both public and private) in which we move and spend time day in day out, i.e., in which we live our lives, could develop over the next 10-15 years. How will we live? And work? What will shape public space and what will influence the things we have around us and use? What will determine their status?

"A room. You’re the fly on the wall. You can see into a foreign world unnoticed and be the silent observer. Anyone live here? And if so, who? What does ‘live here’ even mean? There are traces of someone – furniture, utensils, personal things. Inserted into the lattice of a monotonous grid architecture, the room is initially not much more than a technical skin. False floors, suspended ceilings, provisional walls. In the background a window that shows the room’s location: in view an airport, probably on the outskirts of a big city. (...)"

Grcic asks the right questions at the right time. He first and foremost makes it clear how fundamentally our lived reality is changing. How will we live between worlds of physical and virtual participation? Where is the place where we will process what we experience when we are really present in a room and yet virtually participate in so many others? What does the space look like where information flows to us? Do we increasingly live on a small personal stage that is also a bit like our base camp? Will a room module, in which some of the unredeemed hopes of Modernism revisit us, act as the unit that provides us with all the necessary utilities? What does that imply for the furniture we use?

Grcic is no skeptic who defies progress. He focuses on the issue of how we can get a handle on the innovations that are changing our everyday lives and make use of them. Forever online, here today, there tomorrow, at some point we nevertheless find ourselves in a private, secluded domain. It is no coincidence that Grcic cites a 15th-century painting that now hangs in London’s National Gallery as the source that inspired his Life Space: Antonello da Messina’s “St. Jerome in his Study”. Insulated from the world and yet still connected to it, the humanist sits pondering over his books – as do we today thanks to “plug and play” – surrounded by everything we think we need in order to stay in contact with the world, with mundane questions and problems.

Does this spawn a conflict? Do center and periphery collapse if you can be on your own and yet at the same time everywhere and in the midst of things? What scope is delivered by upgrading built space, including heating, air conditioning, WLAN, loudspeakers and so on? Do we now only need a few outstanding items of furniture (a table, a chair, an armchair, a recliner) if everything is so mutable? Is our personal space but a collage of our needs, expressed among other things through furniture? And then there’s the view out of the window, of an airport which embodies any number of forms of change between which we move since starting to seek to orient ourselves in the transitory space of the present.

Photo © Vitra Design Museum, Mark Niedermann

"Where are you? This place could be anywhere the world over. In the middle of nowhere. As a viewer you’re at the center of the scene. A kind of workshop, a designer’s work space, cut off from the outside world, yet also totally networked. There’s something conspiratorial about it as if it hosted a secret. The space is dark. Black Box, privilege or necessity, the chosen one or the damned. How will the designer’s profession change going forwards? (...)"

So this is where the work gets done. This is where ideas see the light of day and decisions mature. Grcic’s Work Space reflects and condenses the change taking place in the world of work in general and in the activity of the designer in particular. Work and home spaces meld, new technologies shift activities from the hand to the eye (and not just in design) to enable what results from the effort to be transformed back into an object using the latest manufacturing techniques. Old and new technologies exist side by side – the new, the customary and the tried-and-true gel. We open a book while also researching in blogs and chat rooms. The designer creates something on-screen, but also builds a life-size model, and thus relies on both analog and digital tools.

Can the different technologies be used beneficially? What does the symbiosis of them actually look like? How can the one enrich the other without access routes, methods and technologies getting in one another’s way? Grcic’s proposal is surprisingly honest and realistic. He shows things the way they are, doesn’t preach an ideology or paint some future only in rosy colors. He soberly presents how his own approach is changing. He isn’t presumptuous, leaves things unanswered, but does not shy away from capturing his experiences in an image. Somewhere between research lab, data room and workshop the new awaits, although we cannot yet give it a name and haven’t yet grasped it in all its consequences.

"The camera zooms out and gives us a view of the big picture. You are in the public space. You are standing on a platform with a view out over the world. It is awesome, sublime. An artificial world that has inserted itself down through the millennia into the fabric of our planet – buildings, streets, lights. A fantasy of dreams and fears. The image it serves up has many levels and aspects to it, is never unequivocal: an enigma that allows for different truths. (...)"

To Grcic’s mind the public space is a non-space, a dis-place, somewhere in-between. His image of public space is consequently multi-faceted and more unsettling than beguiling. The green city, café conversations and vegetable patches on a roof-top terrace are nowhere to be seen. No gridlocks or networked mobility. On the contrary. We enter fenced-in terrain that includes or excludes, defining our own place in relation to the surrounding urban utopias and dystopias. Citizens, companies, the state, the media, here multiple interests collide. The empty, barren space– which a few specimens of the “Chair One” share with “Landen”, a seating object that resembles the abandoned undercarriage of a lunar module – is surrounded by a panorama that Grcic has not influenced at all in terms of aesthetics and content. It was “painted” on-screen by film artist Neil Campbell Ross. The result: a remote scene in which elements of existing cities, fragments of strange countrysides and seemingly industrial spaces blend with sci-fi themes. And Grcic does indeed manage to capture the ambivalences of the public as a space in an enigmatic image in which hopes and fears intermarry.

"In the course of time, an archive of things has arisen in my studio. My own design projects mingle here with foreign objects, references, materials, found items, artworks. They’re stood in rows like dominoes, and obey a simple ordering logic: An object tells a story that refers to the next object, which in turn takes up the story of another, and so on. There is no chronology, only the red thread of a story based on free association. (...)"

The world as filmic narrative in a display case. Object space outlines Grcic’s own cosmos. It is a personal space where the viewer learns a lot about Grcic’s way of ordering thoughts and things, forging links, finding inspiration. Chairs, books, images, household appliances, luminaires, a clothes hanger with a beard: They all form a treasure trove of ideas and things, role models and found objects. Whatever you look at, you’ll find it full of references and cross-references, associations and stories.

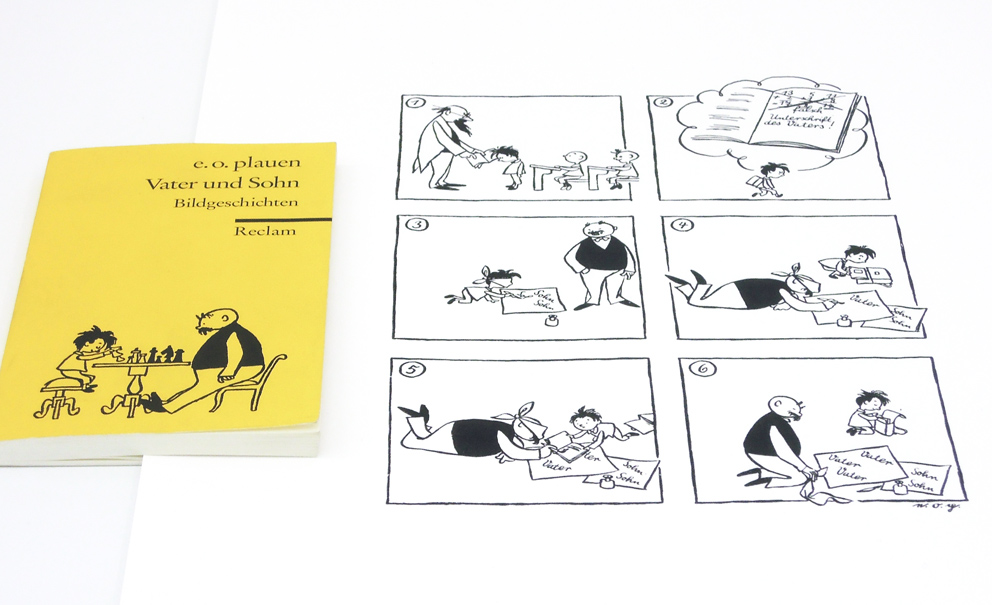

The poster and catalog of an exhibition by Marcel Duchamp, next to it “Wanda”, the dish rack inspired by his bottle rack, and also catalogs on Carl Andre and Haim Steinbach refer to artists and their oeuvres. “Box” by Enzo Mari in yellow, Grcic’s favorite chair, an archive box made from the same plastic, and a Reclam book with E.O. Plauen’s illustrated stories on “Vater und Sohn” are all linked by color. “Missing Object” stands next to a Macintosh Classic, somehow equating the indent of the enigmatic piece with a PC screen. A poster of the Monza 1000-kilometer race in 1971 is linked via the sharp banked turns of the track to the backrest of Grcic’s “Monza” chair designed in 2009 ... and so on and so forth.

What is assembled here only at first sight resembles a conventional design show. Because even simply viewing this “archive of things” goes much further. It highlights how everything is interconnected, ideas with objects, colors with memories and preferences, shapes with obvious or quite tenuous references. The bits are all held together with the person, by Konstantin Grcic, who gives it all order, allowing it to tell us about him and his way of seeing and designing things. Even if it is a contingent order, and the stories and histories could be told differently by someone else. What swiftly becomes apparent is that objects ain’t just objects.

Photo © Vitra Design Museum, Mark Niedermann

Once you’ve wandered round the exhibition rooms and installations, preferably more than once, you’ll notice that Konstantin Grcic has succeeded in presenting an exciting panorama of the present day. It is a complex picture that he paints, in which space and time and history permeate one another, a pictorial story about and painted using objects and ideas and history, whereby these crop up in the design process only to disappear again, inspiring and shocking. However sober and awkward Grcic’s panorama may be as a whole, like many of his designs, these images of the present and future will remain lodged in our memories for a long time to come. Whether they are a promise of something to come or admonish us given what has already been is something the designer deliberately leaves unanswered, aware as he is of his and our responsibility for the world around us.

Konstantin Grcic “Panorama”

Vitra Design Museum Weil am Rhein

Thru September 14, 2014

Daily 10 a.m. – 6 p.m.

From February 1 – May 24, 2015 at

Z33 – House for contemporary art in Hasselt.

Further international stages will be announced later.

The catalog is edited by Mateo Kries and Janna Lipsky,

And available in a German and an English version for EUR 69.90.