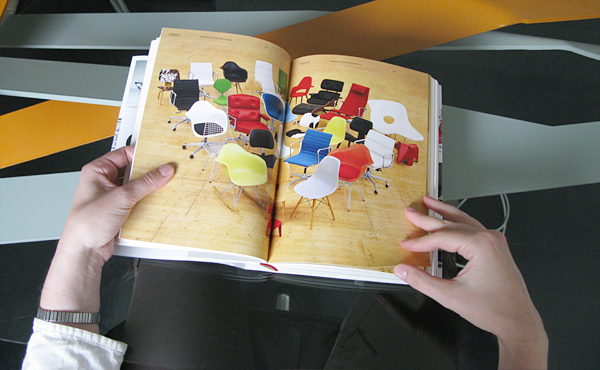

“Projekt Vitra” is the self-representation of a successful company. And yet the book, with its intelligent essays, with its products arranged like families for a wedding photo, with historical and contemporary pictures and documents, is more than a corporate history. At times it gives a short history of design, at others an example of which architecture is able to achieve, at still others everything revolves around the transformation of the world of work, or the special features of industrial design processes. Or we witness how regional roots and skilled entrepreneurial actions can generate an independent industrial culture and how very personal relationships can lead to global networks. It all started with Eames and Nelson Love investigations It is a fact that had the meeting with Charles and Ray Eames not taken place, Vitra would not be Vitra. And thus even today, when far-reaching decisions need to be made, we still like to ask the question: What would Charles say? Only the designer George Nelson, or so Fehlbaum declares (no-one spoke as intelligently and wrote so well about design as he did) had a similarly large influence on the development of the company. Thus even today, it is the blend of a pioneering spirit, interest in research and determination which makes Vitra successful. Charles Eames called the interplay of dedication and passion “love investigations,” which evidently not only leads to good design, but also to its successful production. Finest architecture Even the factory in Weil is no ordinary factory, but a first-class architectural campus, on which architecture, art, design and industrial culture meet in a globally unique way. The reconstruction of the complex was started after a fire in 1981. While the first factory halls by Nicholas Grimshaw are still geared to Anglo-Saxon high-tech, an architectural spirit of discovery was soon to manifest itself with the dynamism of Frank Gehry’s “Vitra Design Museum,” Zaha Hadid’s Suprematist fire station, the minimalism of Tadao Ando’s conference pavilion and a production hall by Alvaro Siza. Fehlbaum had a good nose. They were trailblazing: Zaha Hadid’s small fire station was the first building she realized, Gehry’s and Ando’s buildings were the master builders’ first in Europe. Nothing is isolated here, it all works together. Between the solitaires, which are connected to form a collage, is Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen’s sculpture “Balancing tools”, a gate made up of a pair of pliers, a spanner and a screwdriver and a symbol of manufacture, and now a “Dome” by Buckminster-Fuller, a gas station by Jean Prouvé and bus stops by Jasper Morrison have also been added. The ensemble, formed from pure signature architecture, is to have its crowning finale this coming year, when Herzog & de Meuron’s Vitra-Haus, playfully composed of vertically stacked gabled houses, and the circular factory hall for Vitra-Shop by the Japanese designer duo SANAA will be inaugurated. Collage as a recipe for success Be it on the architectural campus, in the Vitra Design Museum, the Home Collection or in Vitra’s Office Worlds, the principle of collage reigns everywhere. Fehlbaum, inspired by his meeting with the Eames and their house in California, never saw furniture as isolated. He was always convinced that it must not have a pointless existence, cut off from life, in swanky showrooms and only determine the dreams of design aficionados. Thus is was no coincidence that Vitra did not champion individual items of furniture, but created entire product families, complemented by special editions and solitaires only here and there. For in the transition to postindustrial society, private and public aspects merge. Life and working are increasingly intertwined, everyday life is networked with the media; and because in addition, even small families no longer provide a meaningful point of orientation or set a standard for design requirements, the home can no longer be just a place of withdrawal or of representation. This means that consequently, furniture must respond to diversity, not strive for uniformity. This results in collages of the private sphere and patchworks of the different needs of work. Thus, at Vitra, we assume “that the responsibility for the master plan of individual living can never lie with the manufacturer, but with the user. Therefore there can never be a typical Vitra home. The user creates his own personal world from heterogeneous elements.” Designers as authors We can hardly deal in any other way with the “authors,” as Fehlbaum calls the designers, graphic artists and architects with whom he collaborates on a long-term basis. The list is as long as their names are illustrious. In the design field alone, it ranges from the Eames and Nelson via Verner Panton, Jean Prouvé, Antonio Citterio and Alberto Meda to Maarten Van Severen, Jasper Morrison, Ronan & Erwan Bouroullec and Hella Jongerius. However, Fehlbaum stresses that the division of roles is precisely not that between principal and agent, but rather two free entrepreneurs, namely, the designer and Vitra, look for the best solution together. “Vitra’s task,” says Fehlbaum, “is to offer the stimulating environment, the technical support, good conceptual discussion and constructive criticism.” This is not yet a guarantee for success, but it is a good prerequisite. Breadth of vision thanks to unsparing analysis Yet Vitra’s success is not just attributable to breadth of vision, passion and a fortunate entrepreneurial hand. As we can gather from each of Fehlbaum’s essays, it is also based on a clear, unsparing analysis, from which proposals grow which can contribute to solving aesthetic, social, urban and atmospheric challenges. Fehlbaum, and this sets him apart fundamentally from other entrepreneurs in the furniture industry, makes proposals; he does not order and does not promise the impossible. He knows that people have to solve their problems themselves. Thus his ethics are oriented on the relationship of a host to a guest. How to avert office disaster In terms of the permanently changing world of work too, an analysis of social needs forms the starting point of the search for solutions. “We are all familiar with office disasters,” says Fehlbaum. “At the same time, we know that we can avoid them.” Here, he talks of the range of concepts spanning from Tayloristic beginnings via the idea of a “humanization of the world of work” to the “civilization of large spaces and support of the form of work suited to them,” to which Vitra has committed itself. If the workstation initially took the place of the desk, now the old office has become a “marketplace of knowledge.” Now it all depends on creating a balance between communication and concentration, exchange and withdrawal. “Net’n’nest” is the current catchphrase, meant to combine “networking” and “nesting.” Where designers flourish This book is a real treasure for every design enthusiast. And even though the diversity of contemporary design is by no means exhausted by what Vitra produces, when reading it we still sometimes become envious that we cannot be involved in all the activities of this exceptional company. Or, as the designer Hella Jongerius puts it, “As a designer you hope that the client points you in the right direction, that they have an expert opinion themselves and a vision in relation to the future collection we are trying to create. It is also important that the client trusts me as a designer, gives me space and respect, contributes ideas in the initial phase of the process and offers support at the development stage. And the client must have the financial muscle to actually allow products to become a success. Vitra offers all this. Its corporate culture aims at letting a designer flourish.” Projekt Vitra. 1957-2007. Locations, products, authors, Museum, collections, symbols; chronicles, glossary. Cornel Windlin and Rolf Fehlbaum (eds.), (Birkhäuser Verlag, Basle, 2008), 400 pages, hardback, €39.90

A lot is different in this book. Not owing to arbitrariness or because a graphic artist got carried away, but because a lot is different at Vitra. The essays are stimulating, the photographs informative, everything is soundly processed, well-designed, thought-through and expressed clearly. Simply Vitra-like. Sometimes with a touch of Pop art, sometimes minimalist, sometimes narrative. Even the first sentence of the introductory text by Rolf Fehlbaum, the spiritus rector of the whole thing, essentially says everything, albeit in a very condensed way, that then gets spelled out over 400 pages: “Projekt Vitra started in 1957 in Basle and Weil am Rhein when the founders of the company, Willi and Erika Fehlbaum, began production of furniture by Charles & Ray Eames and George Nelson. We still produce this furniture as our classics today and we are still based in the Basle metropolitan area. However, a lot has been added over the years.”