"Design Art" was until recently regarded as the new collector's market par excellence. Limited editions enticed buyers such as Brad Pitt and wealthy collectors, who had tired of functionless art or who simply had no idea what to do with their money. Some designers who were anyway working in a conceptual context as opposed to as classic industrial designers, were thankful for the unusually large amounts of money paid in the art market even for a pre-model. Fairs such as "Design Miami" and "Design Art London" came into being as parallel events to renowned art fairs, to benefit from the hype. Last year saw the first "Object Rotterdam", an off-shoot of "Art Rotterdam". The financial crisis, however, had already begun, the "big party" was over and the gallery market was starting to change, and not just in the Netherlands.

A lot of what in the last decade was on view in the field of "design art" was nourished on the pioneering work Droog Design had been doing in the 1990s in the Netherlands. Droog was the stepping stone for design stars such as Hella Jongerius and Marcel Wanders, and repeatedly provided the impetus for current design trends: for the disrespectful treatment of design classics, for storytelling, humor and irony, for the quotation of historical product shapes and for the exploration of traditional ornaments and handicraft techniques. Years ago, however, "Droogdesigning" emerged, as it were, as a new international style that could no longer be observed just in the work of Eindhoven graduates, but in that of design graduates all over the world - and whose overstrained wacky designs were often far removed from the former quality of Droog.

At this year's "Object Rotterdam", which was held at the beginning of February, there was very little of this still on display. It would seem that a generation of designers that consciously distances itself from Droog and is responding to the financial crisis with mature works, is now enjoying success. The co-founder of Droog, Gijs Bakker, said of the designer Stefan Scholten of the design duo Scholten & Baijings when he was still a student that he was not a "Droog designer". The fact together with his partner Carole Baijings Scholten is now one of the most successful Dutch designers is proof of the generation change that has been underway in Dutch design for a few years now: The Droog founders Renny Ramakers and Gijs Bakker no longer work together; Droog has lost its role as a source of inspiration for Dutch design. As one gallery-owner put it: "At the end Droog was just not exciting any more. For too long too many designers failed to address shape. That has changed now."

And so the second edition of "Object Rotterdam" offered on the one hand, as was to be expected, the over-priced multiples, some criticism of classics, a bit of functionless deconstruction and a glut of the jewelry galleries that have a strong tradition in the Netherlands. There were, however, also some designs of surprising quality - even if at the press conference the head of the fair Fons Hof merely accorded the design fair the function of "giving a little bit more volume to "Art Rotterdam."

The "Total Table Project", for example, put back on the agenda a topic that only recently had supposedly still been considered too applied and un-cool to elitist "design art": The laid table. Kiki van Eijk and Scholten & Baijings designed totally contrasting and yet in their own way convincing complete ranges of contemporary tableware - from crockery, cutlery, and glasses to the tablecloth. Carolina Wilcke displayed her beautiful degree work "Tafelgenoten", which involved her taking vessels varying in shape and material and arranging them as a modern Dutch still life, as well as her wooden object "KamerRekwisiet" which, strung with different-colored yarns, becomes a 3D picture in the room. Aldo Bakker, Gijs Bakker's son, also had several designs on view: Though his "Urushi" lacquered objects and stools made of different types of wood are becoming wickedly expensive intricate handicraft objects, they are not content with being somehow "wacky" or "critical", but are in search again of the aesthetic appeal of shape and finishes. The presence of a large number of his works, which he himself says are deliberately different from the concept emphasis of the Droog design approach, was almost patricide.

There were also several objects on view at "Art Rotterdam" that most certainly would not have been out of place at the smaller design fair: Experimental glass pieces, which can be used as vases, stool-like sculptures, explorations of everyday and household objects - each and every one proof of the fact that not only design has moved closer to art, but art to design as well, as was in evidence, for example at the Venice Biennial as well. Just which discipline assumed the role of the superficial and which that with the emphasis on content, is no longer as clear-cut as only a few years ago. If anything, the much-quoted crisis seems to have done the overheated world of "design art" some good: Wacky and provocative alone is no longer enough; a new exploration of formal quality and contents is emerging - and that could possibly be of interest for classic product design.

Shadow of light by Koen van den Broek

Shadow of light by Koen van den Broek

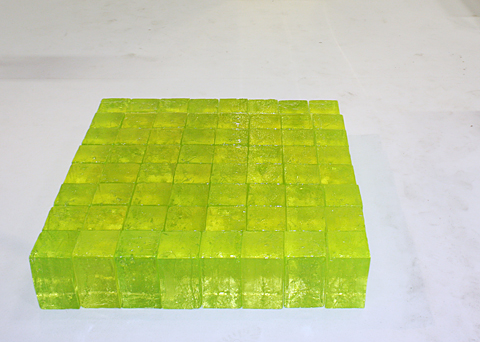

Object by Ann Veronica Janssens

Object by Ann Veronica Janssens

Total Table Design by Scholten & Bajings

Total Table Design by Scholten & Bajings

Total Table Design by Scholten & Bajings

Total Table Design by Scholten & Bajings

Stool no.2 by Aldo Bakker

Stool no.2 by Aldo Bakker

The Apartement by Brodie Neill

The Apartement by Brodie Neill

The Flax Project by Christien Meindertsma

The Flax Project by Christien Meindertsma

Hotel New York

Hotel New York

Restaurant of Museums Boijmans Van Beuningen in Rotterdam

Restaurant of Museums Boijmans Van Beuningen in Rotterdam

Shopping Center De Bijenkorf by Marcel Breuer in Rotterdam

Shopping Center De Bijenkorf by Marcel Breuer in Rotterdam

Tassenkast by Lotty Lindeman all photos © Stylepark

Tassenkast by Lotty Lindeman all photos © Stylepark

Tafelgenoten by Carolina Wilcke

Tafelgenoten by Carolina Wilcke

Entrance area at the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen in Rotterdam

Entrance area at the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen in Rotterdam

Playing with tradition by Richard Hutten

Playing with tradition by Richard Hutten

Carbon 451 Lamp by Marcus Tremonto

Carbon 451 Lamp by Marcus Tremonto

Jewel by Karen Pontoppidan

Jewel by Karen Pontoppidan

Scholten & Bajings

Scholten & Bajings

Total Table Design by Kiki van Eijk

Total Table Design by Kiki van Eijk

Unit(s) by Dimitri Vangrunderbeek

Unit(s) by Dimitri Vangrunderbeek

Entrance area of Museums Boijmans Van Beuningen in Rotterdam

Entrance area of Museums Boijmans Van Beuningen in Rotterdam

WC Unit by Joep van Lieshout in Museums Boijmans Van Beuningen

WC Unit by Joep van Lieshout in Museums Boijmans Van Beuningen