Vaults are high art. It all began with the Pantheon in Rome. Despite the existence of many examples to be seen in Modernism - Le Corbusier’s Mediterranean barrel vaults, Pier Luigi Nervi’s fantastic concrete dome, Eero Saarinen’s flying space swings and Louis Kahn’s archaic brick archways – enthusiasm for the vault appears to have significantly subsided over the past fifty years. This makes the London Blavatnik School of Government, which is currently undergoing extension works headed by Swiss architects Herzog & de Meron and due for completion in 2015, is all the more striking; for their blueprints include among others a vaulted roof, complete with white herringbone tiling: An unequivocal reference to the great Rafael Guastavino (1842-1908), who could adorn a public space with vaulted roof like no other.

Today, Guastavino’s thin-tile Catalan vaults can still be found in over a thousand buildings in the USA, two hundred of these in Manhattan alone – whether Grand Station, Ellis Island Hall or Carnegie Hall. John Ochsendorf, professor of building technology at the prestigious Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge, and author of “Guastavino Vaulting: The Art of Structural Tile”, has been conducting research into the historical Catalan vault technique and its potential for modern sustainable building. Nora Sobich spoke to John Ochsendorf.

Nora Sobich: The name Rafael Guastavino is barely known of today. Things were quite different a century ago.

John Ochsendorf: It is the story of an industrial architect from Valencia who worked in Barcelona for many years before he then came to the USA. His company was successful right into the 1940s. Even today we certainly don’t know of all of his vault systems. Each month we discover something new.

The construction technique used for the so-called thin brick vault, as the Catalan vault is sometimes called, appears extraordinarily modern in its well-considered use of materials, like a perfect execution of Sullivan’s “form follows function”.

Ochsendorf: Guastavino found himself between the master bricklayers of the Gothic period and those of the Modernist movement. His vaults resemble the genuine wall vaults to be seen in cathedrals or the Pantheon in Rome, he just used thin tiles. One of his greatest vaults has a diameter of 30 meters at barely 15 centimeters in thickness.

You have already used this fascinating technique to recreate a few vaults at MIT…

Ochsendorf: They still use these techniques at various locations throughout the world, especially in Spain. But we are only just beginning to comprehend the efficiency and beauty that can be found in these forms. Guastavino’s spiral staircases were three-dimensional constructions created without a single piece of steel or concrete. We just can’t recreate something like that nowadays. Even engineers can’t vouch for their stability. Ironically, the New York authorities expressed doubts about the stability of Guastavino’s famous staircase even 100 years ago: He had to have 45 tons worth of sandbags dragged in to prove them wrong. It’s all very fascinating.

... and rather astonishing in times when Zaha Hadid has designed the most ambitious construction using cutting-edge computer technology.

Ochsendorf: Architects like Zaha Hadid conceive forms by probing out the laws of geometry. Engineers are then left with quite a lot of work when it comes to bringing these forms to life; while the forms seen in the Catalan vault are naturally stabile. We are currently in the process of developing computer software to find an explanation for why this is the case and discover how these techniques can be used to create new forms á la Zaha Hadid, just with more awareness of gravity.

For all the Catalan vault’s beauty, Guastavino was a businessman, as the name of his company, which was taken over by his son in later years, reveals: “Guastavino Fireproof Company”…

Ochsendorf: The attribute “fireproof” afforded Guastavino the opportunity to get a foot in the door of the New World with his vault system. Fire resistance was a huge advantage in US towns at the time, whose buildings were still made predominantly from wood.

Guastavino completed hardly any work for wealthy private clients, excluding a few wonderful examples such as the Vanderbilt’s tennis hall, but focused mainly on the public space…

Ochsendorf: Indeed, that was the time of the “City Beautiful” movement. They were creating beautiful urban cityscapes in order to keep pace with the European metropolises. So elaborate vaulting was in demand.

But the thin brick vaulting technique, as you write it, has fallen into complete obscurity over the past fifty years. Why?

Ochsendorf: Modernism of course had a very displacing effect here. Just take a look at one of the great icons of modern architecture, Mies van der Rohe and his Barcelona Pavilion built in 1929, a beautiful linear system. The foundation is a double-curved, thin brick vault. But this was hidden away underground because it didn’t correspond to the Modernist ideal in terms of aesthetics.

In terms of your research is it “learning” about historical building techniques that plays a central role?

Ochsendorf: For me, it is the use of history as a basis to develop new possibilities for building that is decisive here. Today, it is a challenge to prove that historical construction systems are also suitable for the future. Their use of predominantly natural materials is, after all, one of this form’s important advantages.

... but they don’t meet the requirements of today’s safety and building regulations.

Ochsendorf: As previously mentioned, it is often very difficult for engineers to explain the stability of such a system. And so, today’s building regulations leave very little leeway for such vault systems even though our predecessors spent centuries developing and indeed implementing these constructive forms and were just as smart as we are today. Furthermore, modern building regulations are developed primarily for industrial materials.

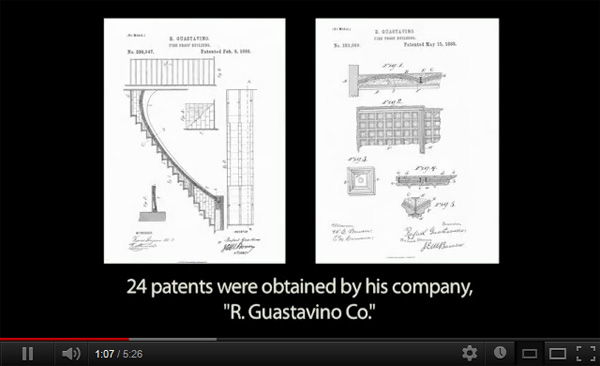

Guastavino held many patents. Did he actually advance the historical vault system to such a considerable extent?

Ochsendorf: This is the subject of an on-going debate. In the Mediterranean region around Barcelona and Valencia, the tradition of the vault technique, which has its roots in the Moorish culture, dates back over six centuries. But the Guastavinos (father and son) were very innovative. They permanently adapted the technique to suit the needs of the market; they even teamed up with a physicist from Harvard University to develop an acoustic tile, which was covered in little holes that absorbed noise. This enabled them to furnish huge train station halls and museums with vaulted ceilings for the very first time. However, some were of the opinion that the Guastavinos had simply used a national asset for their own personal gain.

You write that Guastavino had a demonstrable influence on Barcelona’s ground-breaking Modernisme movement. On the somewhat younger Gaudí too?

Ochsendorf: There is evidence to suggest that Gaudí did actually visit the Asland Cement Factory in the northern Spain built by Guastavino in 1903. Gaudí was of course much more innovative and took the vault technique in an entirely new direction, as can been seen in his Casa Milà in Barcelona. For Guastavino it was less a matter of the construction in itself, rather the decorative power of the tile pattern, which would also be of great importance for Gaudí in later years.

So the Guastavinos’ story is also the story of the aesthetic and constructive adaptation of a traditional construction technique to meet high demand and the needs of a, if you like, modern mainstream market?

Ochsendorf: Indeed. In the USA, the Guastavinos were given the chance to implement these traditional construction techniques on a large scale, which of course would never have been possible in Spain.

The craftsmanship however does appear to have been very costly. How many workmen did the Guastavinos employ?

Ochsendorf: That is something that unfortunately we still don’t know. But during its heyday, the company had branches in twelve different US states.

Are there no records? The Guastavino family enjoyed a relatively long legacy, until 1962.

Ochsendorf: There are very few, and this is due to nothing more than chance. At the beginning of the 1960s, when Guastavino had already fallen in obscurity, the American Gaudí expert George R. Collins noticed that the vaulted ceiling in the Colombia University Church in New York had the same tiled vaults as many of Gaudí’s buildings in Catalonia. He began to look into this and so called the Guastavino Company in Massachusetts. He was then informed that company had just closed down. All records had already been thrown in the trash. Collin was only able to salvage a few drawings and some letters.

Now back to the end of these Spanish pioneers: Is it really possible to execute such colorful exemplars of craftsmanship and construction on a grand scale after all?

Ochsendorf: Yes it is, but of course costs also play a notable role here. If we were to now rethink the potential of this system, costs would most definitely have to be brought into consideration. Good, modern construction in a world that is greatly concerned with sustainability must also consider the exact costs that will be involved. Vaults made of the simplest of natural materials are not only aesthetically pleasing but are above all sustainable, working to the advantage of the materials themselves, in this respect they are highly efficient and cost-effective. And so, by looking to the past, we are they are absolutely looking to the future too.

Guastavino Vaulting: The Art of Structural Tile

By John Allen Ochsendorf

Hardback, 255 pages, English

Princeton Architectural Press, Princeton, 2010

48.99 Euros

www.papress.com