Cooperation not Competition

Lorenz Brugger: You come from very different regions in Germany and Chile respectively. How did the three of you get to know one another, end up working together, and come to set up your own architecture practice?

Gonzalo Lizama: It was a very happy coincidence. We got to know each other during our first Master’s semester in Berlin and were if you like the “leftovers”. The program hinged on sets of two students. I was the last person to join and we were given a special dispensation to work as a trio. We were able to realize our first design under Professor Dr. Matthias Ballestrem, and that worked really well. Subsequently, our work was even presented in French architecture journal “L'Architecture d'Aujourd'hui”. But what made it special was that we got on very well and there was and is no competition between us. We sat down together, talked a lot, spoke a lot about architecture for days on end sometimes, without coming up with a specific design. We sometimes see the same thing with other architects who are often wasteful with their resources and are then frustrated when the outcome is unsatisfactory. In principle, I think it’s fine to rely on your intuition. In principle, I think you can rely on your intuition often and then sense when you’ve found the best concept.

Anyway, we decided we should take this happy coincidence seriously and pursue the idea of establishing our own practice. What then actually happened was this: After graduating we all worked for two years in different offices. Lukas Specks was the first one of us to register with the Chamber of Architects as an architect and initially we worked with him under his name. Once we had also registered with the Chamber as architects, we were able to operate as a company. That was how Studio Loes came about. Later I went to South America for a dual-degree program. The other two went back to university, first as tutors and then as research assistants. Yet we always kept our practice running and took part in competitions for students like the “Concrete Design Competition”, which involved us being invited to a concrete workshop in Dublin. That led to us embarking on other excursions together and our friendship grew deeper as a result. We have now worked together for almost 12 years. We are very much aware of the others’ merits, we each know what the others find challenging, and how we need to respond to one another. I think that is something that is truly invaluable. We have a very democratic approach to things. We talk at great length about how to deal with issues concept-wise and strategy-wise and you quickly realize when someone is overruled. To my mind, you can make better progress this way than if you have two opposing opinions but don’t have anyone to tip the scales.

Do you always collaborate on all aspects of the project or does each person have their own area and then you put the various parts together at the end? Who does what at the practical level?

Gonzalo Lizama: Naturally, we deal with several projects at the same time and then we quite playfully assign a hat to each project, as in the hat the project lead has to wear. I mainly supervise interior fit-out projects and then manage them from start to finish. That aside I work a lot in what the German system classifies as service phases one to four, in other words, planning permission for buildings, multi-storey and housing construction or loft conversions. Onur is mainly responsible for the later service phases, i.e., five to eight and nine. He is very interested in technology. Thanks to his work at the university and his training at a university of applied sciences he is very skilled in structural engineering and is brilliant at getting his way on site. And then there is Lukas, of course, who can turn his hand to anything. He can contribute to all service phases and step in anywhere. That’s how we assign the work. Each of us manages three to four projects simultaneously, so that can mean up to 12 projects running at any one time. That’s the only way we can expand and extend our skills set. Compared with the many one-man outfits who can of course not manage as many projects we get through a great deal more thanks to the fact that the work can be spread across six shoulders. If conflicts arise or one of us gets stuck, they can rely on getting support from the others. After all, architecture boils down to overcoming problems and mastering challenges. So, it’s always good being able to consult one another, be it with regard to building laws, planning policy, but also when it comes to technical or planning issues.

Of course, we also have our favorite projects where all three of us try to get onboard in equal part. And then we tend to work longer and more deeply on those projects. Which is why from an early date we started to include a controlling program in order to keep an eye on what exactly we are spending our time on. Our experience from other offices shows that often you work on a project you feel very passionately about so long that your fee has been gobbled up three times over and we can’t afford to do that. We have a time management system in place as we have employees who we want to retain. Consequently we didn’t have to sack anyone during the Covid pandemic. That is something that’s very important to us – experiencing this collective feeling and getting on well with one another. That said, we are also aware that we are a step on the ladder for our staffers, and that they choose us because we arguably have a more modern and more progressive approach to contemporary architectural topics.

How do you tackle projects and how do you manage to move from the brief for a task on to finding a solution? Looking at your projects, materials are a key issue. Does the material play a role in the design from the very outset?

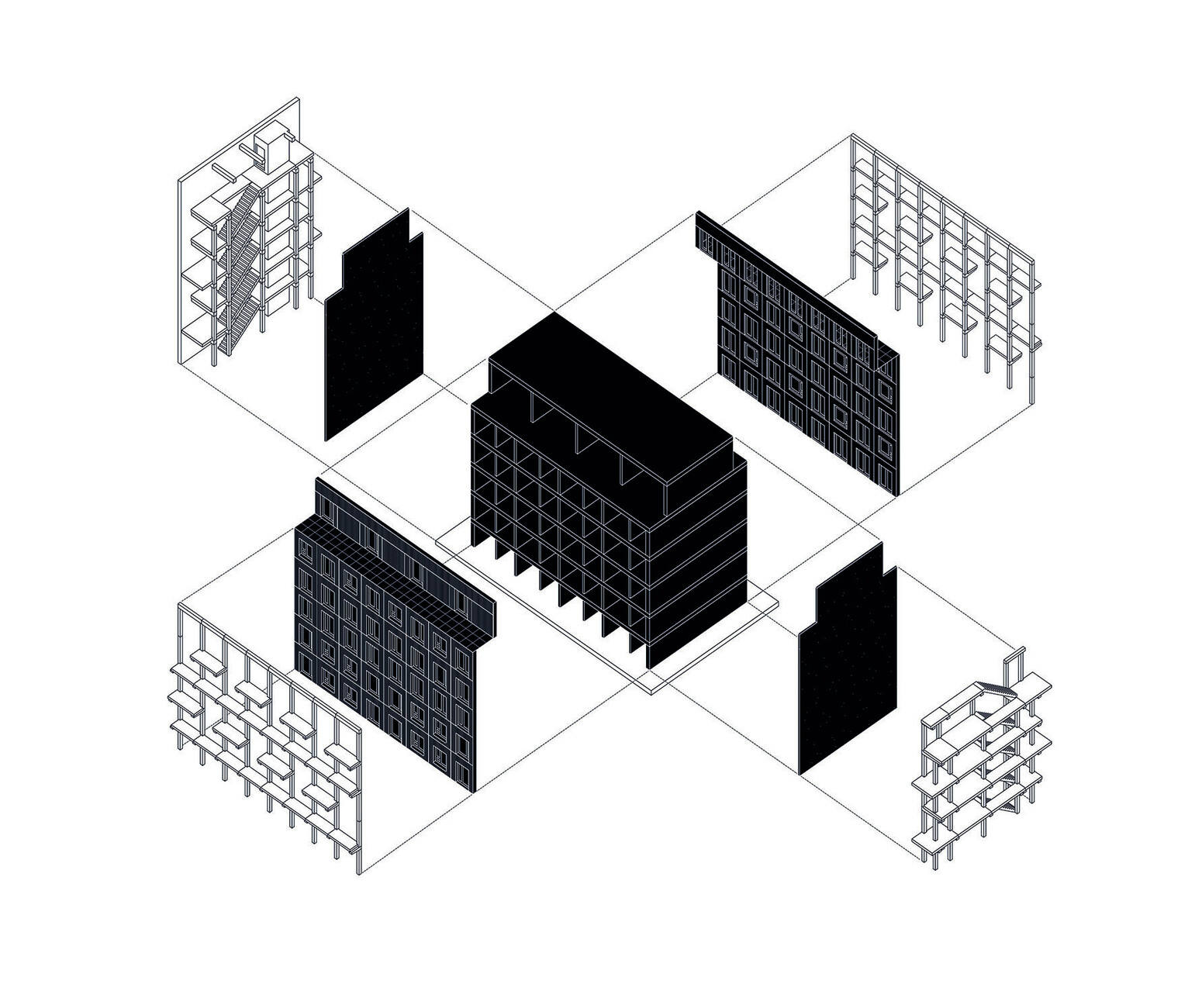

Gonzalo Lizama: The most important thing for us is the agenda involved. Ultimately, that’s what distinguishes architecture from art. We don’t operate in a vacuum, there are always parameters, certain materials, building regulations, time, and financial constraints and much more. The framework for and context of the structure is important for us. Very early on we faced the question of how logistics should be considered, especially in the case of loft extensions and increasing densities in Berlin’s urban environment. Where do we stand the crane or what can be prefabricated? How can small components or modules be moved through the stairwell or the entrance? These sorts of things weren’t dealt with in our studies. You learn them on the job as it were. We had done quite classical training in structural engineering. It’s quite remarkable that we learned things like that in 2012 at university and afterwards nobody was interested in it anymore. We taught ourselves all about ecological building and in particular about timber construction. And it is not yet a given that architectural offices are familiar with timber construction or with the problems that arise for acoustics, spans, or even the options in timber production: How are components joined and what are the maximum dimensions? How large can the modules be, ranging from facade modules and wall modules through to entire bathroom modules? We are definitely very interested in pushing ahead with timber construction and think it makes a lot of sense working with a modular timber construction method. In the urban context it is a fitting and contemporary answer to the space problem and the complicated matter of trying to assemble things in a confined inner courtyard, for example.

“Element” is the first large residential building you have completed. How would you characterize the building? How did you come up with the idea of a modular construction?

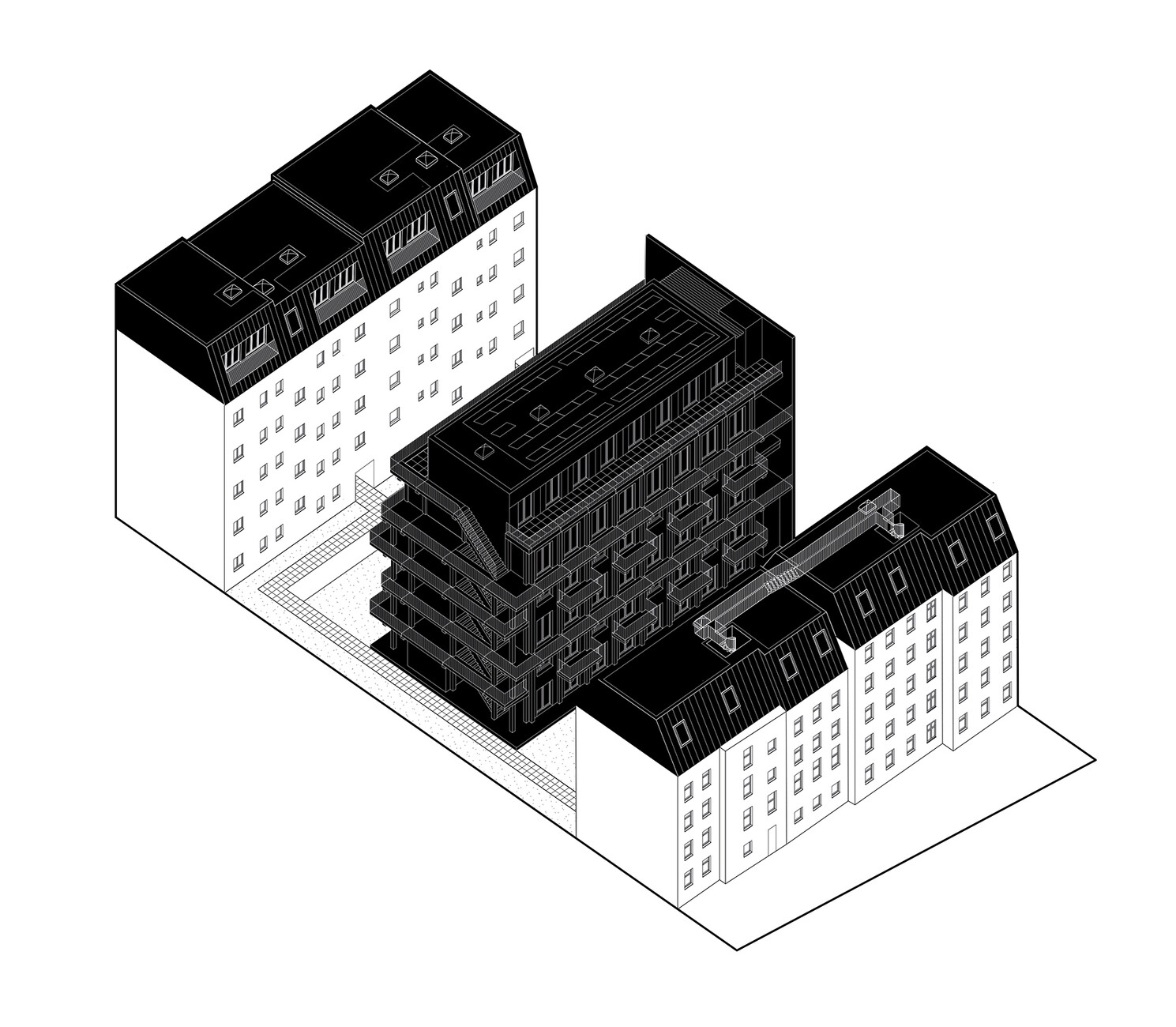

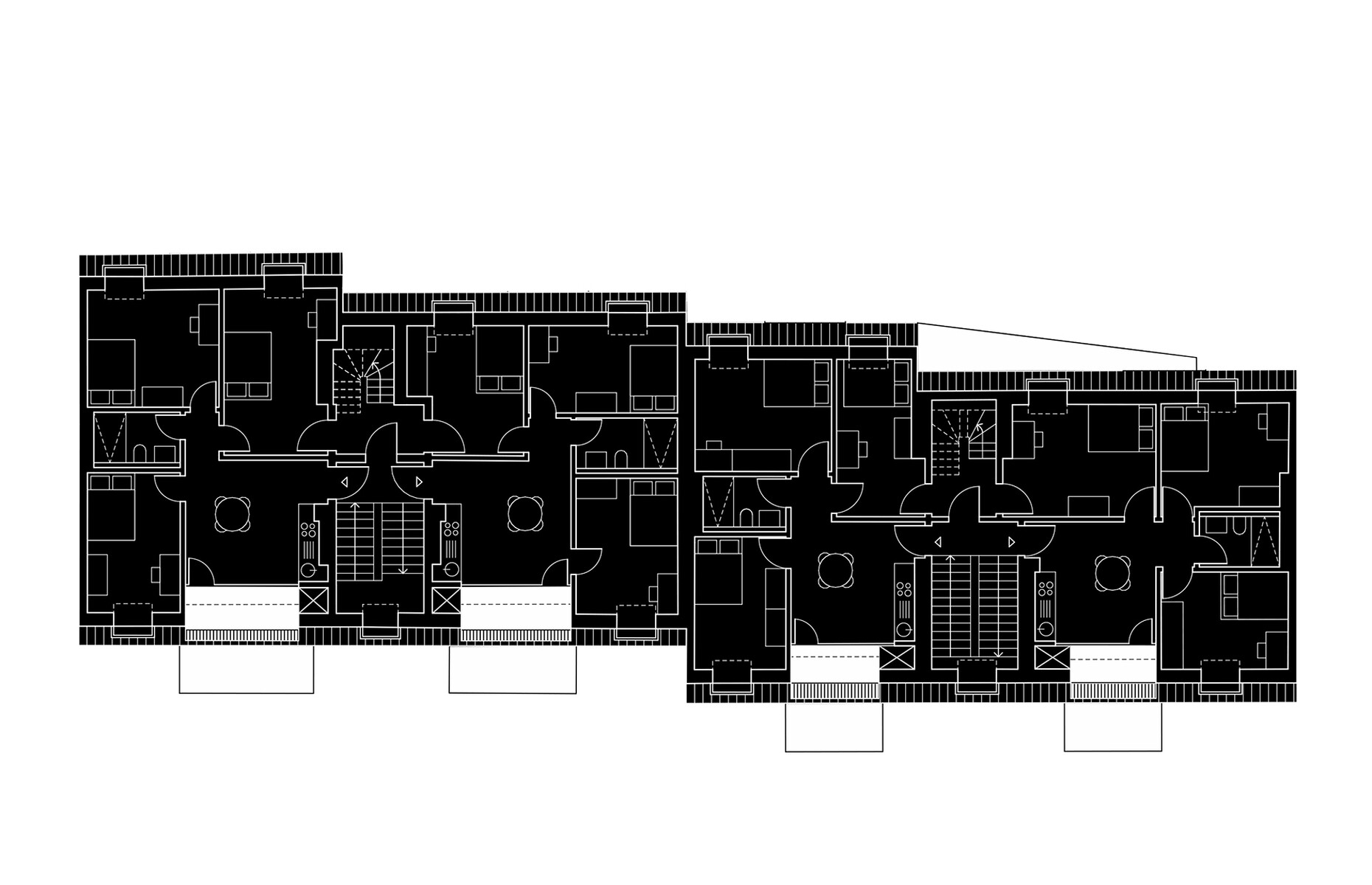

Gonzalo Lizama: We looked at modular construction and the typology of covered walkways at an early stage. This also has something to do with timber construction: building an elevator shaft in concrete and then installing the timber construction around it would probably have tripled the construction time, but we had the entire timber building up in four weeks and then came the prefabricated reinforced concrete parts, and after that the modules. We thought if you already have access to the covered walkways then it would be an advantage if the residents and also the occupants in the front and rear building had a new space as a kind of public living room. We wanted to encourage users to appropriate the outdoor space for themselves, in other words the open space in front of the apartment and of course that works all the better if you avoid unnecessarily large television rooms. And the concept also envisages that the smaller apartments can be combined and the spaces arranged as you see fit. Essentially, the apartments are intended for certain groups of people: students or for people who work in the neighborhood.

You started out with smaller furniture units and interior design in wood. To what extent did such items help you realize the “Element” project?

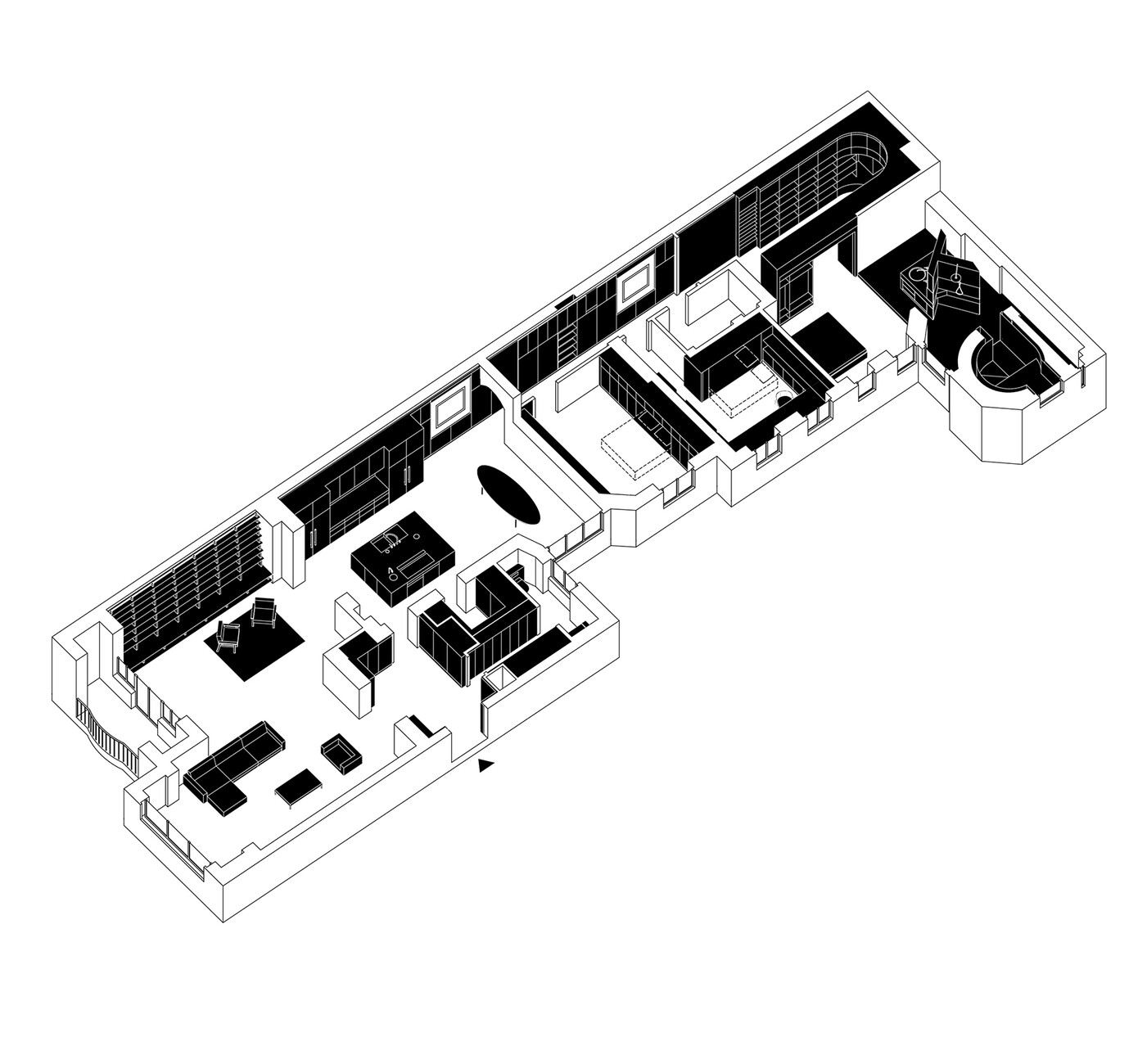

Gonzalo Lizama: To be honest, interior design was initially a means to an end. It was often a matter of getting into stronger contact with cabinetmakers, producers, and manufacturers. In the end, however, I think the architecture is just as valuable as the contacts and the contractors involved. We are always consulted to see if we know anyone to do carpentry work, create the building shell or install windows. I have to say that from an early stage we have always endeavored to ensure that the rooms we design have a human scale. That’s why it’s important to consider the proportions of kitchens, countertops, or furniture. Moreover, in the case of “Element” and “Lingot” we always planned the building with the furniture and interior design in mind. The rooms are very compact and we have to take this into account when designing to make sure it works in the end. That’s why it’s important to take the interior design into account. If I could go back in time I would probably train as a carpenter. To my mind that makes a lot of sense if you want to understand how things work in timber construction.

In fact, we have developed and produced our own tables, luminaires, and seating for most of the projects parallel to devising the architecture. That has proven so successful that we are now selling these articles via a subsidiary called Loes.Beta.GmbH: Items that we realized for particular projects have been further developed and are now ready for retail sale. We have noticed that arguably also as a result of the Covid pandemic many people are taking a greater interest in their own four walls than they previously did. We are observing a trend in which to put it simply most people sees themselves as interior designers and want to get involved in designing their interiors. Years ago the car was a status symbol, now it is a bespoke kitchen by bulthaup. I also believe that a greater awareness for the sense of “home” has developed, which hopefully will result in a greater appreciation for it. Ultimately, your living space is an extension of your personality.

Initially the new website of Loes.Beta.GmbH will feature seating. We will present benches and stools. That said, we also have tables on offer, and we have come up with an idea that we call “Interlock”. Our furniture is produced in such a way that it can be sent as a flatpack. Which means we do not need much packaging material, and the products are easier to ship. It’s also important to us to be able to offer our products to everyone, which is why they can only be found on the internet. We are keen to offer furniture for design afficionados, although we want it to be affordable even to students. We also produce a lot of small series so as to give people the feeling that they are buying something special, but also because it’s important to us to be able to produce our products inexpensively. We make a point of developing furniture that is cost-effective to produce, can claim to be design, that features smart connections and retails at a few hundred euros

Moving forward, what other tasks appeal to you?

Gonzalo Lizama: We intend to take part in more competitions again. And we would definitely like to tackle other areas apart from classic interior design and housing, be it a workshop or a university building, say a forum where know-how is shared. Our Master’s thesis was called ‘Forum’, after all; it was about viewing the sharing of knowledge as an integral part of the building, how people from a variety of cultural backgrounds and knowledge come together and how they can be united at different times of the day. This was then combined with a community center, a library, café, and marketplace.

The Student House in Braunschweig by Gustav Düsing and Max Hacke which was recently honoured with the Mies von der Rohe Award 2024 is also based on a concept similar to a knowledge forum. What do you think of the building?

Gonzalo Lizama: The EU Mies Award was conferred on a modular steel building. I am intrigued by the fact that the project has broadened horizons in the professional world and advanced the debate on the use of different materials in architecture. It’s not always a matter of using only wood or only steel, but about achieving a mix that is as sustainable as possible. We are delighted for Gustav Düsing and Max Hacke, who both work in Berlin. I like to think that people are teaming up and entering into collaborations. We should see architecture much more as a joint venture and therefore be more willing to share our know-how. Studying architecture is in itself very competitive and the system of architectural competition makes us believe that there can only be one winner and all the others are second or third best and less valuable, but I think there should be a much greater collaborative spirit and more mutual support for colleagues. At any rate, things seem to be moving in this direction with a greater emphasis being placed on collaboration and less on competition.