House of the Future

For anyone looking for a thorough education in architecture the Carolo-Wilhelmina Technical University in Braunschweig was always a good choice not only during the three decades when Meinhard von Gerkan lectured there. Anyone with more artistic aspirations or looking for celebrity design status moved to Stuttgart, Aachen or went abroad. So when an unusual building is realized at Braunschweig Technical University it is something that attracts widespread attention, it is not likely to be a spectacular, ingeniously designed signature building but rather one that is innovative yet rock-solid and exemplary, a building that sets standards. We are talking about the new Study Pavilion right next to the university’s historicist main building. The new build seeks to provide answers to several questions, such as, for example: How will we learn and study in the future? For Braunschweig’s architecture students the legendary drafting rooms with that very special atmosphere generated by collective learning where students work, discuss, and celebrate together have always been the focal point of their studies. However, more recently this way of working has spread to many other departments and is increasingly replacing conventional lectures held from the front of class.

Since this type of study in self-organized groups is per se an informal arrangement it has always been accommodated informally as regards space and organization, usually in rented old buildings. Now for the first time a new building has been realized at TU Braunschweig to provide precisely such an informal place of learning: the Study Pavilion. The plans came about from a competition among the professorial assistants in the Faculty of Architecture. There were two winners, namely the young Berlin architects Gustav Düsing and Max Hacke. Maybe one model that influenced their concept was the Fellows Pavilion of the American Academy in Berlin’s Wannsee district, which Düsing was involved with as an employee at the Barkow Leibinger practice, or perhaps it was the glass exhibition pavilion which von Gerkan inserted in the courtyard of the Braunschweig TU building, or maybe the two architects were inspired by Mies van der Rohe and Philip Johnson with their famous houses made solely of glass.

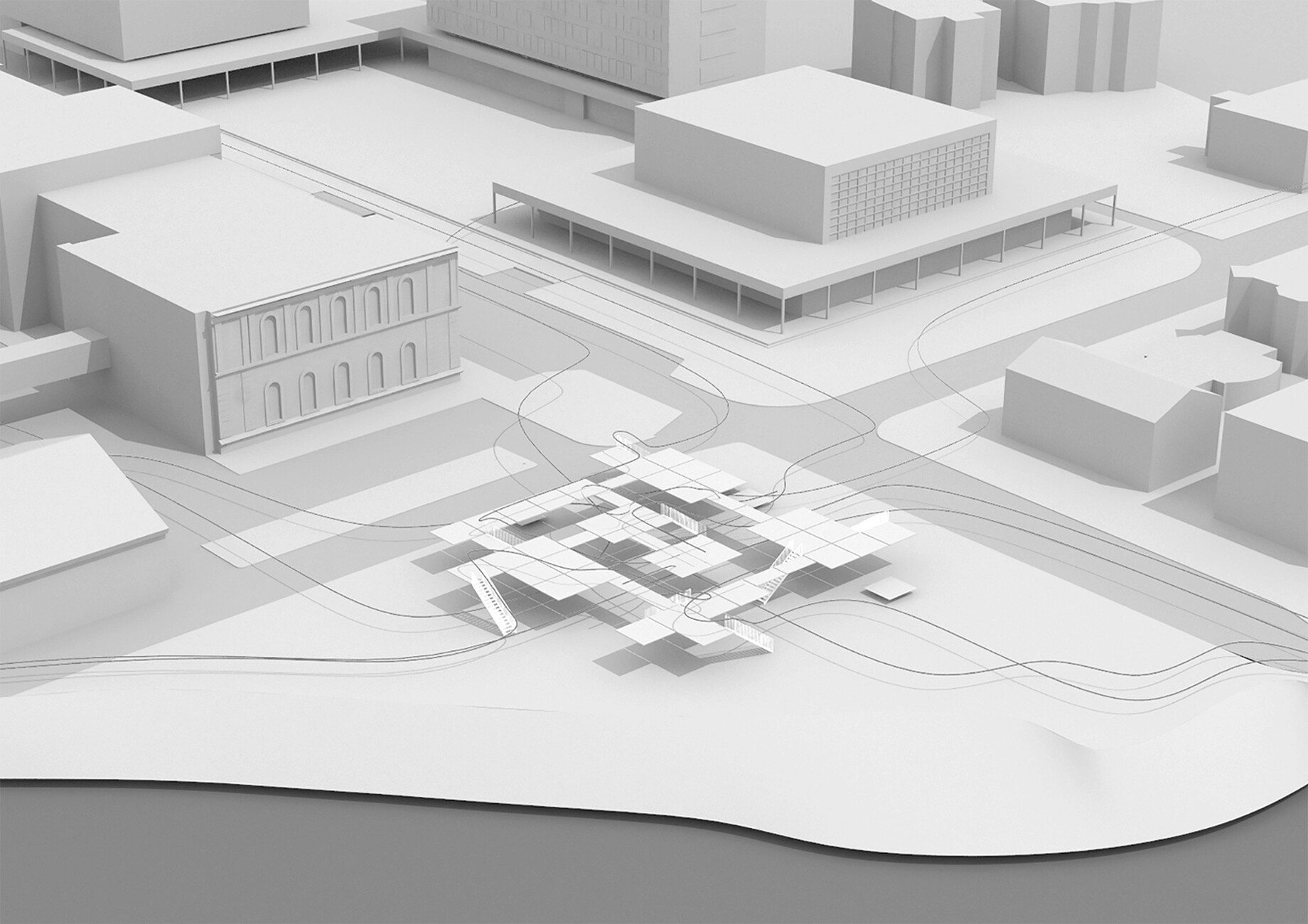

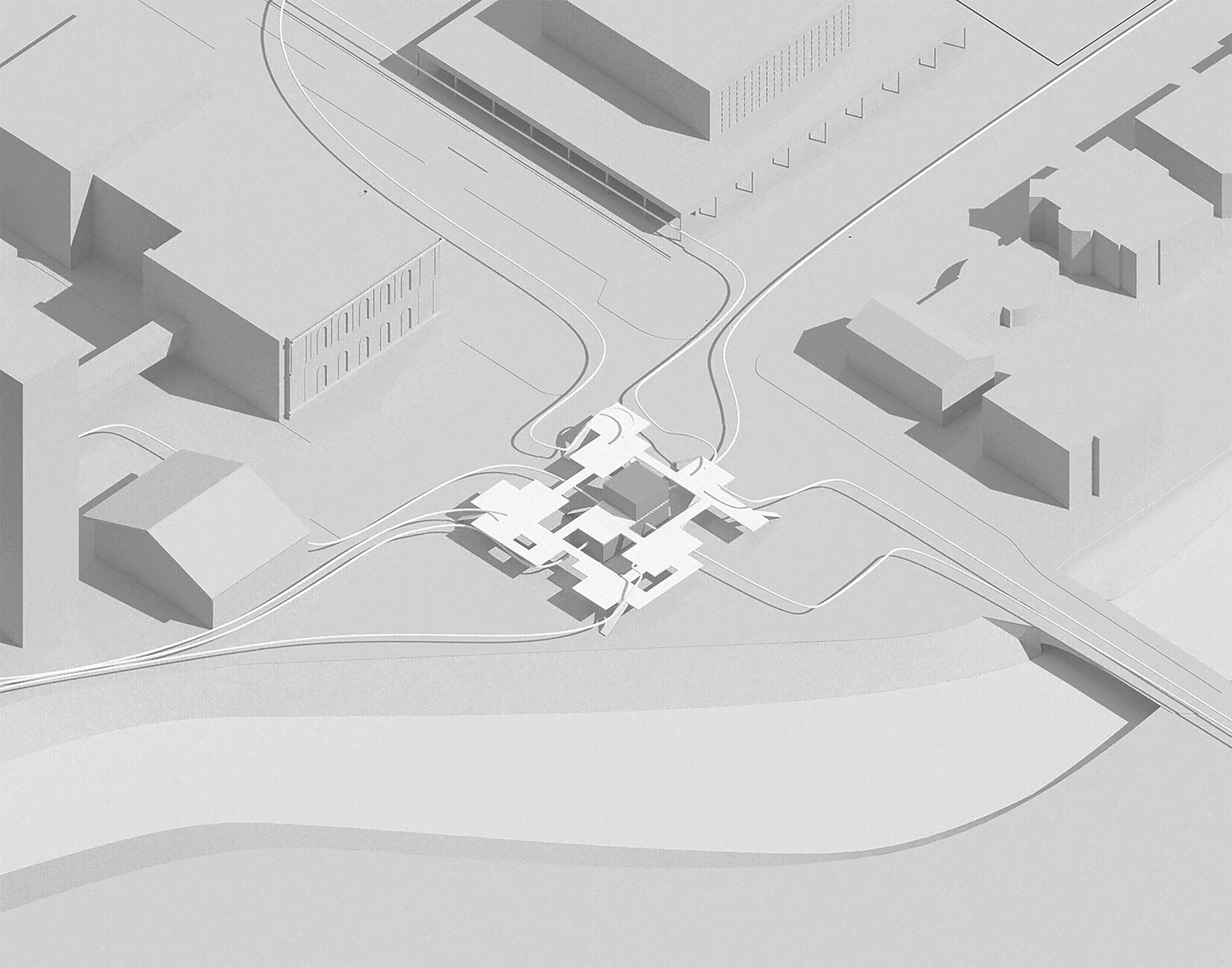

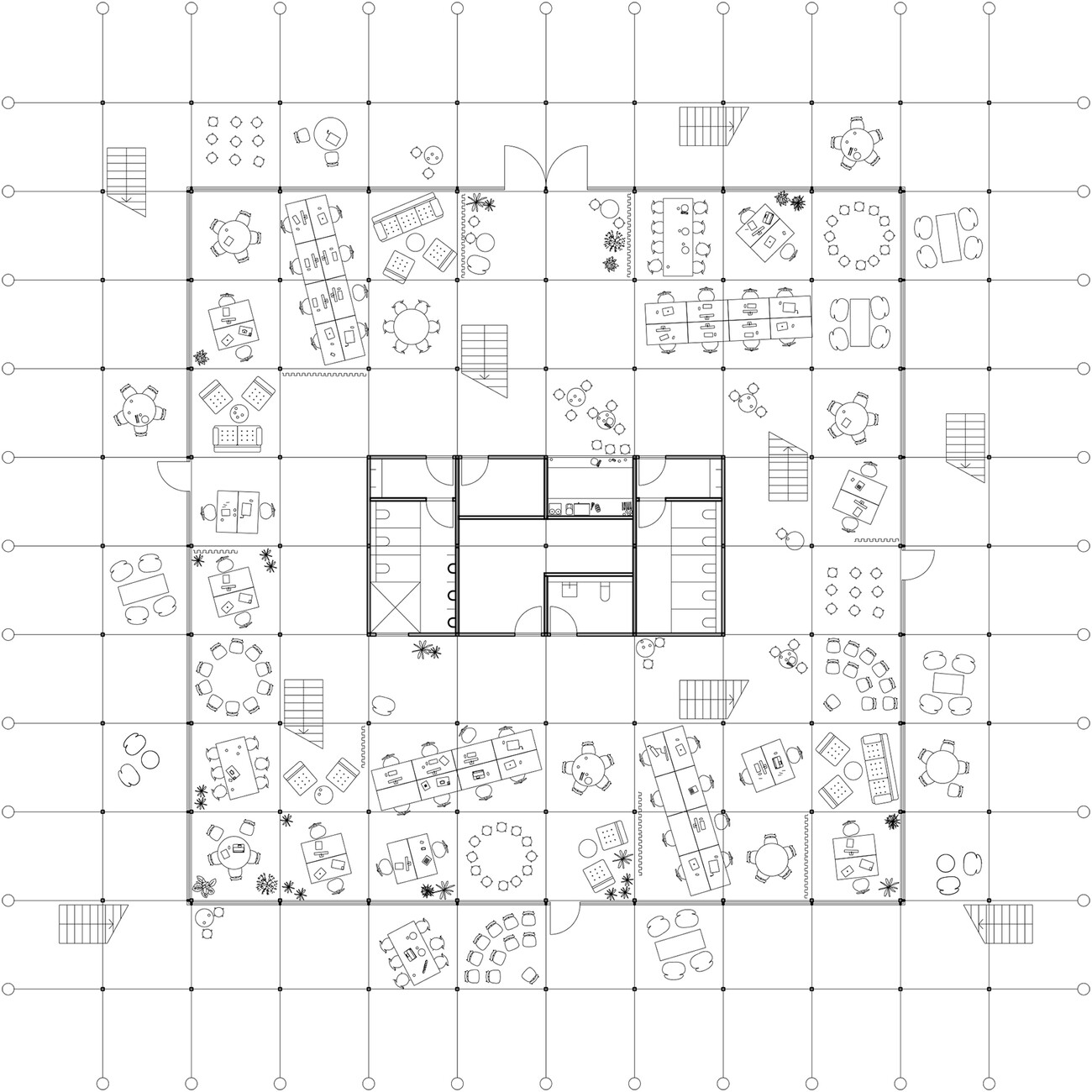

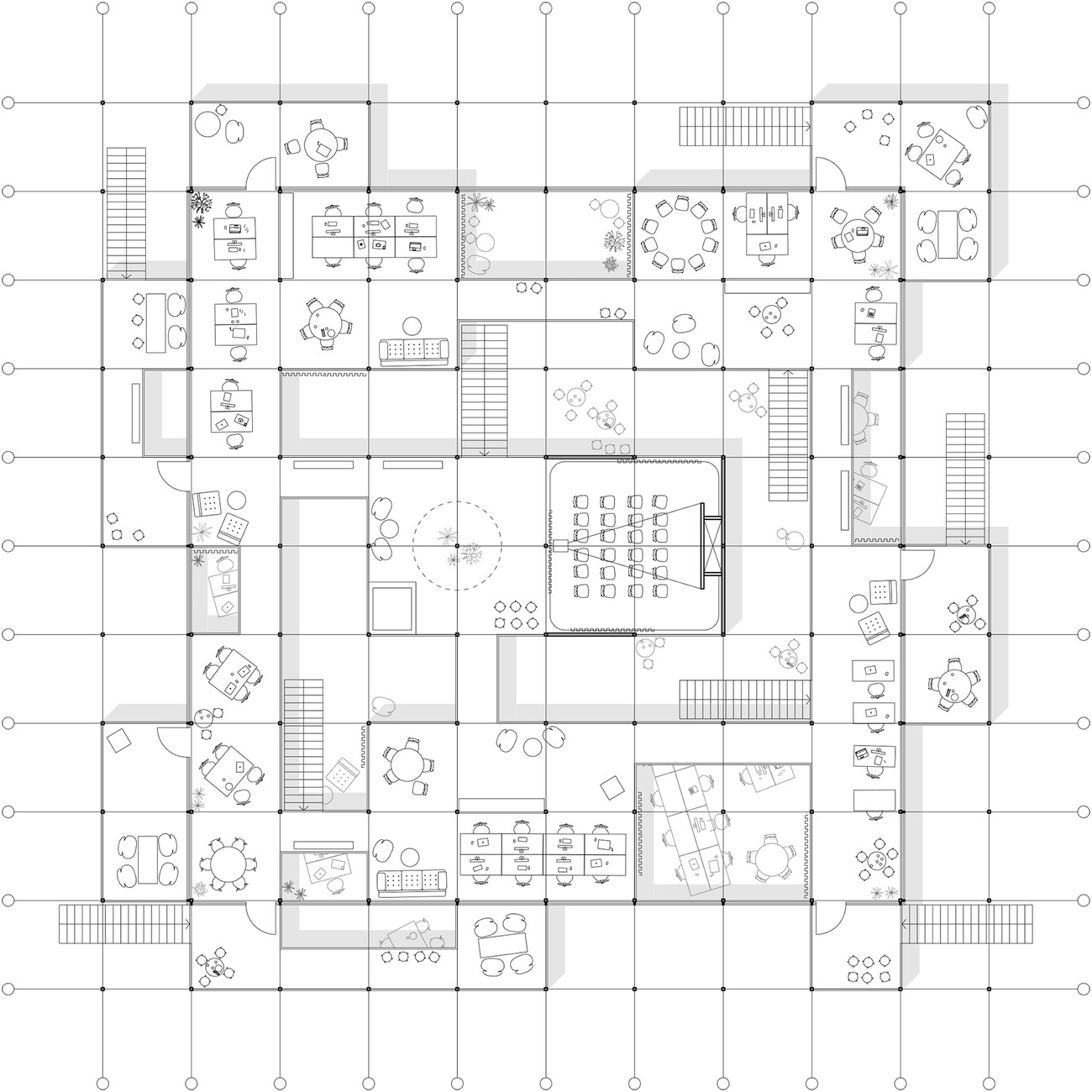

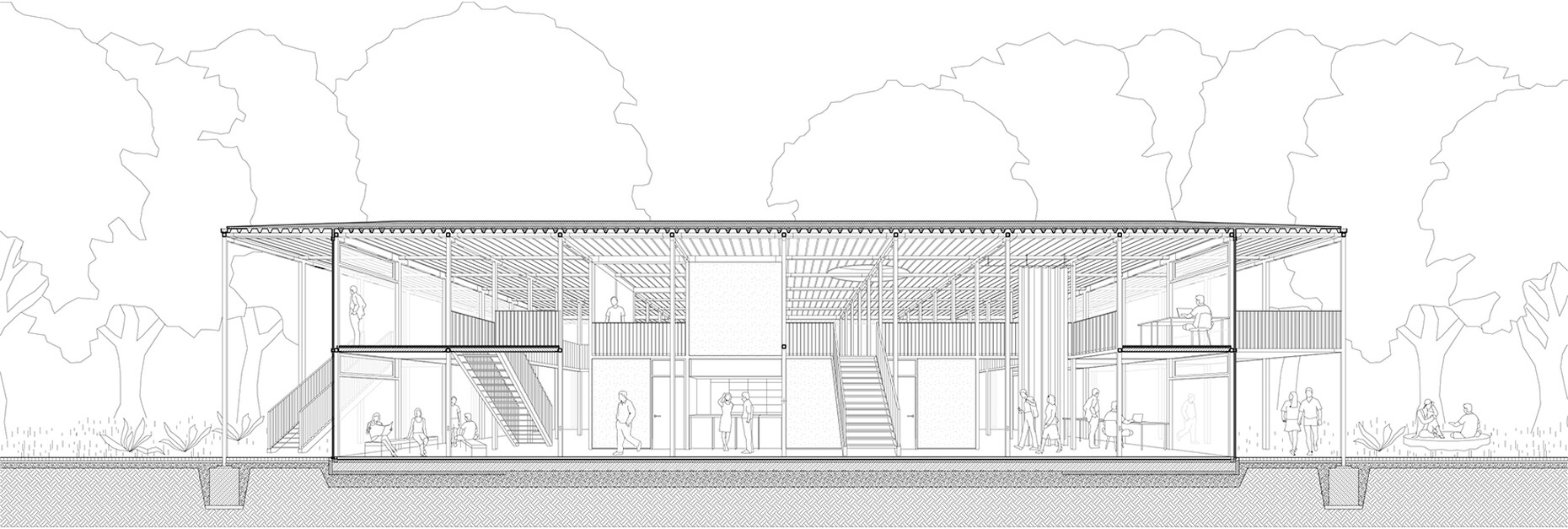

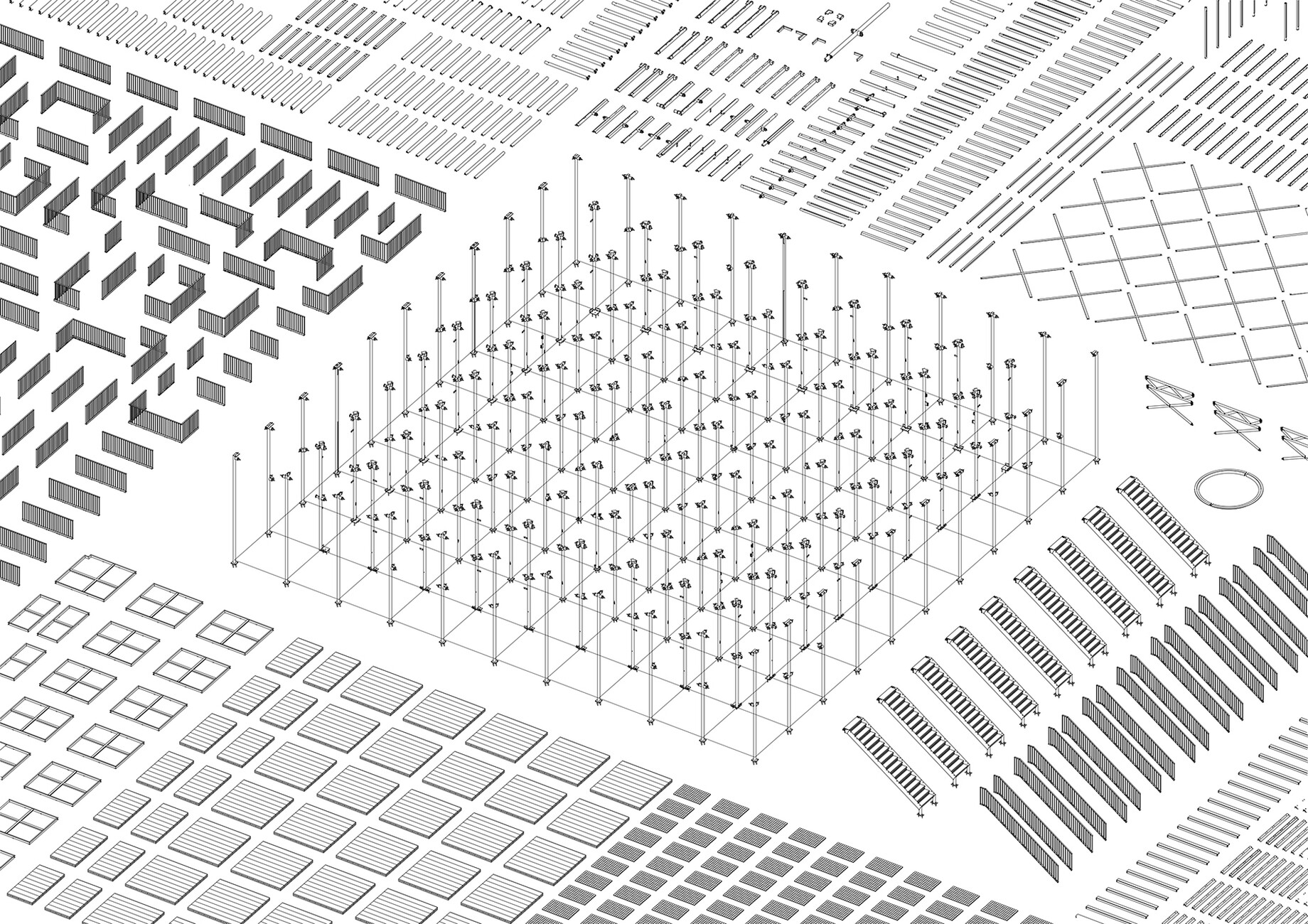

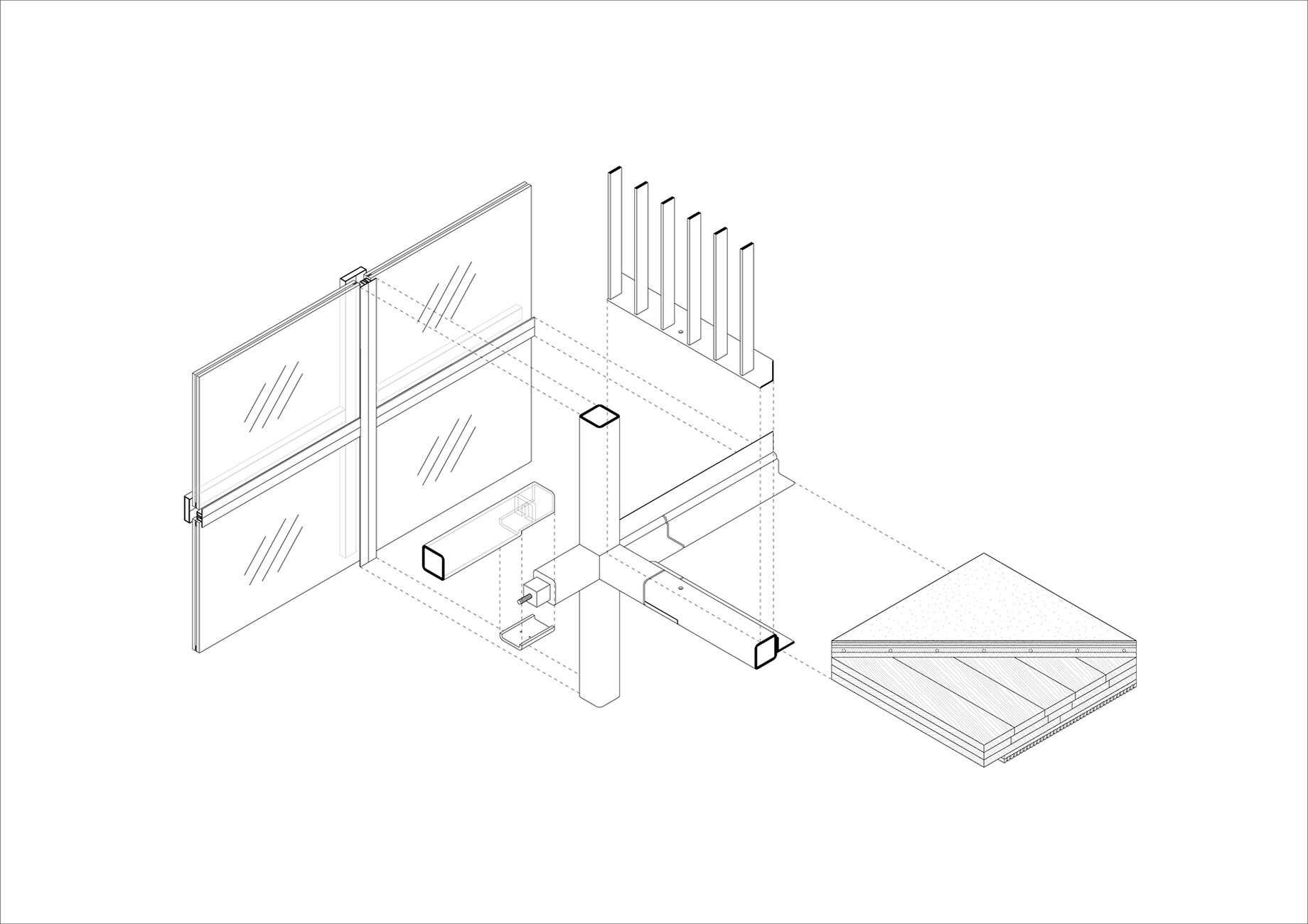

At any rate, the Study Pavilion is a two-story glass pavilion, a light steel structure surrounded by terraces and external staircases, and entirely without closed exterior walls. Some 200 workstations are available across two levels. The tables and seating can be arranged as needed. Students simply need to find an empty seat, open up their laptop, and can start work. There are also lockers for architecture students where they can store their model-building material. For them in particular the building could not provide a better instructive visual model; it is demonstratively sustainable, sparing on resources, energy-saving, and boasts a refined structural system, which the young architects developed in collaboration with the structural engineers from the renowned engineering office of Knippers Helbig. As in a construction kit with identical 10 x 10 cm square hollow sections the 121 columns and beams are set on a 3 x 3 m grid. Only in the center of the first floor are there some service rooms surrounded by walls and toilets. The floor slab sections are made of wooden panels with fire resistant panels and sound absorption and are straightforwardly suspended in the extremely delicate load-bearing structure and fixed with a few screws. Moreover, there are no diagonal braces. Instead, the nine existing flights of stairs deflect the wind forces into the ground.

The refined steel load-bearing structure is designed so that 95 percent is utilized. You cannot save more material than that. The building is not only exemplary thanks to its modular construction which is low on resources and inexpensive as Gustav Düsing explains: “With the Study Pavilion we want to use structural means to make a contribution to the discussion on circular building.” As a result, the building embraces the forward-thinking cradle-to-cradle principle, because it can be completely dismantled, separated with almost no waste, and recycled. Max Hacke recalls that “we asked ourselves whether it is possible to re-use entire components rather than just the materials or to rebuild a building at some stage somewhere else and in a different form? That is why we developed a modular system as it enables a great number of uses further down the line.”

Nobody would deny that the building standing under trees on the banks of the Oker River is indeed an exceptionally beautiful edifice. That said, it was not planned that the building be beautiful or factored into the design; that has simply arisen from it fulfilling its function and the perfect handling of the material – quite as postulated by pioneers of Modernism such as Mies van der Rohe, Le Corbusier, Buckminster Fuller and so on. And as with Mies’s architecture, there are only a few details, reduced to complete simplicity. For example, it was possible to avoid installing a secondary frame for facades and windows because the steel support frame is precise enough to accommodate the panes of glass that are simply mounted rather than being glued in place. There are no blinds, no sun shading installations. Only a few yellow curtains create deliberate spots of color in the steel structure painted in “Telegrey”. “We designed the building to be largely monochrome in a light gray. The architecture is intended to be restrained, to see itself as infrastructure,” explains Gustav Düsing and Max Hacke adds: “The curtains in a rich yellow are meant to add touches of color and simultaneously stand out clearly from the rest of the structure as an interactive element.” Partition walls and carpets are also in pale gray, tables are white, the seating is black, while the wooden ceiling soffits on the ground floor are in natural beech – a neutral, almost distinguished color palette provides the framework for the colorful hustle and bustle that the students bring to the building.

What remains is the question of spatial perception in the bright, boundless “fluid space” which seems to merge seamlessly into the green surroundings. The students arrange work tables into small groups, form individual islands or even larger groups temporarily. Numerous access points from the outside via the external staircases and galleries ensure that you do not have to walk along a corridor past many other tables and groups to get to your own island. Acoustically this wide-open space does not present problems. A combination of carpets, partitions with thick padding, and sound-absorbing tapered metal ceilings make for a subdued sound level from which no individual voices emerge.

Düsing and Hacke teach next door in the university’s high-rise building which is home to the Faculty of Architecture. “The Study Pavilion sees itself as a countermodel to the Oker highrise. We feel that campus architecture should help promote interaction between the students. As we see it, a vertical arrangement of institutes and seminar rooms as we have in the highrise favors the principle of the one-sided transfer of knowledge and hinders an exchange of ideas across the disciplines, not least of all because it prevents chance encounters,” comments Düsing looking back on the duo’s own experiences with the building. You don’t have to seek out other people in the Study Pavilion but you can do, and you know you are all united in studying. “It makes a space available that can host a variety of activities, is not restricted in how it is used, and which generates a communicative, non-hierarchical atmosphere. Students do what they want here,” adds Max Hacke. In many respects, the building which is now occupied from early morning to late at night is a prototype which demonstrates modern construction methods, showcases unusually open spatial concepts, and promotes new ways of learning and studying. It is trulya building with a future, a forward-looking building, and a lighthouse project for TU Braunschweig, which sets an example for others to follow.

Update 2024: The project was awarded with the DAM Preis 2024 and the European Union Prize for Contemporary Architecture – Mies van der Rohe Award.