Spotlight on Women Architects – Mariam Issoufou

Two years ago the Pritzker Prize was presented to Diébédo Francis Kéré, and from then on, at the latest, architecture from Africa has been a hot topic. Regional, climate-friendly, and socially responsible building(s) define many of these projects, which are increasingly influencing the architectural discourse. An almost paradigmatic figure in this development is Mariam Issoufou. Yet this Nigerien architect actually first studied computer science in the USA. She then worked there for several years as a software developer before ultimately switching to architecture. After completing a Master’s at the University of Washington in 2013, she initially joined the united4design architecture collective and soon after founded her own firm, Atelier Masōmī, in Niger. Masōmī roughly translates as “beginning”. In her work, Issoufou critically examines the dominance of Western architecture and the ideal of the star architect. By way of an opposite approach, she often works collaboratively with other architects such as Yasaman Esmaili from Iran. At the same time, she is concerned with the architectural culture of her native country and the historical, social, cultural, and climatic conditions surrounding it as a way to develop her own architectural language.

Despite being inspired by the traditional architecture of Niger, Issoufou is also influenced by more contemporary protagonists – such as Diébédo Francis Kéré or her compatriot Falké Barmou, whose mosque in Dandadji she converted into a community center with a library in 2018. Her influences also include architects like Charles Correa, Balkrishna Doshi, and Louis Kahn – all master builders who were able to combine Modernism with the specific basic conditions of a location and its regional, traditional architecture. The approach of Alero Olympio, a female architect from Ghana who deals with local, sustainable artisanal techniques, construction methods, and building materials, is likewise reflected in her work.

Hence Issoufou often uses mud for her buildings. One example is the Niamey 2000 residential complex completed in 2016, which she realized together with united4design in Niger’s capital city. The two-story ensemble of buildings is made up of six interlocking units that form multiple inner courtyards and roof terraces covered with pergolas. On the one hand, the architecture is inspired by the spatial density of buildings in the region, but it also responds to the climatic conditions. Instead of elaborate facilities technology, the unfired mud-bricks of the masonry ensure the buildings do not heat up swiftly. Added to this, there is a natural ventilation system for the inner courtyards, which are thus further cooled.

For the conversion of the mosque created by Falké Barmou, Issoufou worked with Iranian architect Yasaman Esmaili of Studio Chahar. The dilapidated building in the village of Dandaji was supposed to be demolished, but the two women were able to convince the population to preserve the structure and use it as a community center with a library. To this end, the façade was restored, the roof repaired, and the structure of the clay building upgraded. New elements include bookshelves that simultaneously function as partitions for reading areas, and platforms built with a wood and steel structure that are connected to the ground floor via stairs.

Directly next to the building, there is a new mosque that was also designed by the two women architects and is connected to the existing building via a spacious outdoor area. The respective entrances are directly opposite each other and thus frame the square that spreads out between them. For the new build, Issoufou and Esmaili used unfired mud bricks, like those deployed for the residential complex in Niamey. They also incorporated openings in the building envelope to ensure natural ventilation, while an irrigation system for the plants in the outdoor area features an underground reservoir that stores rain in the wetter months.

Issoufou has also realized a regional marketplace in Dandaji. Here, simple, mud-brick walls enclose the areas for the individual market stalls, which are lined up like little bungalows along the orthogonally arranged access roads. At the center of the complex is a sunken square that is built like a small amphitheater. A large tree provides shade and marks the site, and there is further protection from the sun in the form of the strikingly colored umbrellas made of recycled metal that are positioned above the market stalls. These also function as a ventilation system, as the varying heights of the shades create an air flow that channels the hot air upwards.

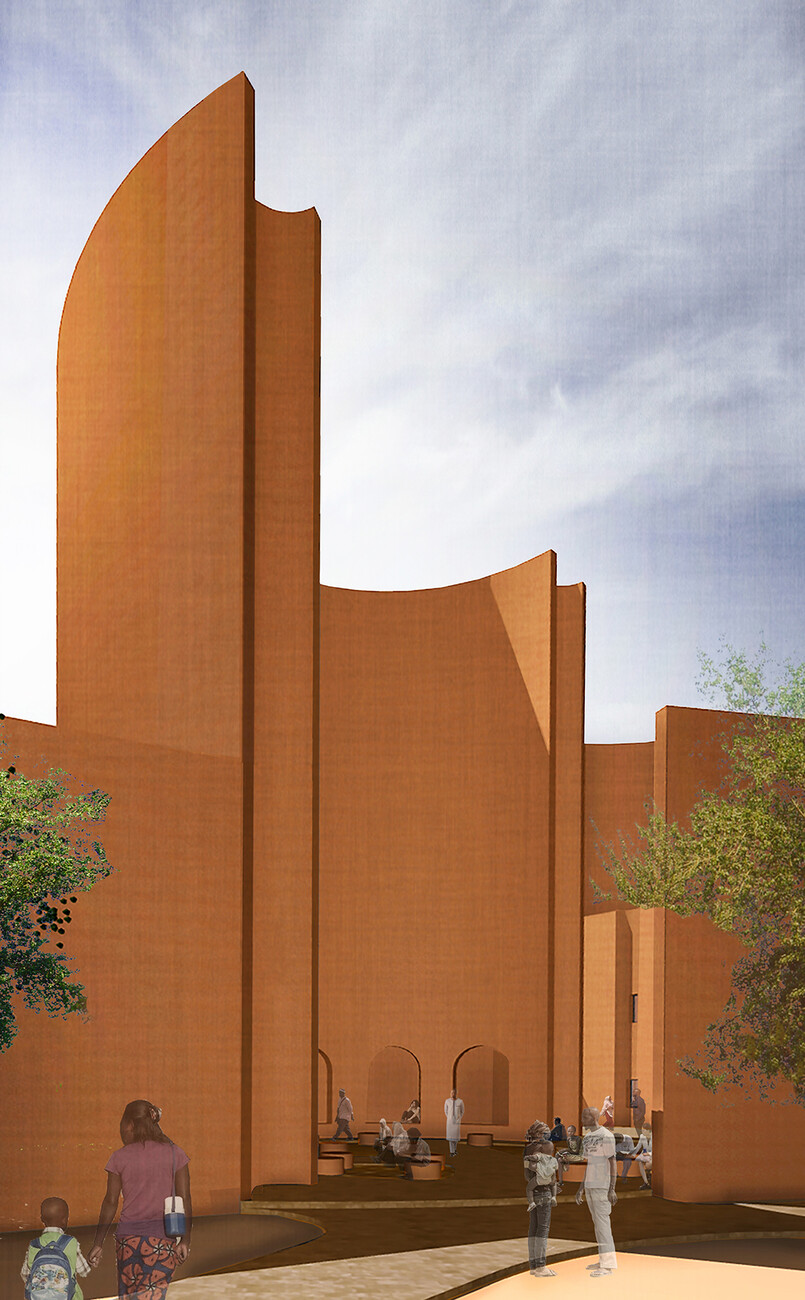

Issoufou is now also planning bigger projects, such as the cultural center in Niamey, which will incorporate public plazas and a large library, among other things. The ensemble of buildings will not only serve as a new meeting point for urban society, but will also connect two parts of the city that were previously separated spatially due to a master plan that was implemented by the former French colonial rulers. In addition, four striking, semicircular towers will highlight the position of the new cultural center in the urban fabric, with their specific arrangement providing shade and ventilation for the plazas. Another example is the Bët-bi museum in the Kaolack region of Senegal, which is likewise a cultural center. Here, the architect has used triangular shapes to design an ensemble in which a sunken square functions as an amphitheater, as in the market in Dandaji. One of the biggest, most prestigious projects she is currently working on is the Ellen Johnson Sirleaf Presidential Center for Women and Development in Monrovia, the capital of Liberia. Here, Issoufou has teamed up with two other female architects, Sumayya Vally from South Africa and Karen Richards Barnes from Liberia. The building will serve as a learning space and will be used for events. It is dedicated to Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, the first elected female president of an African country, who won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2011. The striking shed roofs of the center’s seven buildings are inspired, on the one hand, by architecture from the region, while on the other, they are also designed to dampen the noise of the rain during the heavy downpours in the rainy season.

Mariam Issoufou now also lectures at some of the West’s most renowned universities. Since 2022 she has held the Chair for Architecture Heritage and Sustainability at the ETH in Zurich, known as Studio Atavism. Prior to that, she taught at the Graduate School of Design (GSD) in Harvard, among others. Her aim in her teaching is nothing less than to “challenge the status quo and redefine the way we approach architecture”, as Studio Atavism’s website puts it. The critique of Western Modernism formulated here is an approach that is increasingly shaping architectural discourse. This is evident, among other things, in Atelier Masōmī’s participation in the 2021 Architecture Biennale in Venice, but also in the Biennale two years later, which was curated by Lesley Lokko, a Ghanaian-Scottish architect. Here, the focus was primarily on African architecture, with more than half of the invited studios coming from there or having African roots. Issoufou’s buildings already impressively illustrate how traditional and modern approaches can be combined to create intelligent social and climatic solutions. The extent to which these solutions will eventually shape Western architecture remains to be seen.