Spotlight on Women Architects – Marina Tabassum

Bangladesh is home to hundreds of rivers that traverse the country of 160 million inhabitants in the form of water arteries. Nestled between the Himalayan mountains and the Bay of Bengal it is located in the largest delta region on earth which is no less than half the size of Germany and twice as densely populated. Added to which on the banks of the Buriganga River lies the capital city of Dhaka with its population of 21 million. It is the seat of the country’s government and among the densest and fastest growing megacities in the world. A less known fact is possibly that Bangladesh is home to an exciting architectural scene. Marina Tabassum is one of its best-known protagonists, with her projects spanning everything from prestigious cultural buildings to religious architecture to mobile refugee shelters. One example of her work is the Bait Ur Rouf Mosque in Dhaka, for which she drew on early mosque designs to create an exquisitely composed structure of light and space. The building won her an Aga Khan Award for Architecture in 2016 and serves not only as a place of prayer but also as a community center for neighborhood residents.

Recently, the exhibition "Marina Tabassum Architects: In Bangladesh" at the Architekturmuseum der Pinakothek der Moderne in Munich presented a show of the architect's work for the first time. Among other things, her projects could be viewed there in the form of plans, models, films, large-format photos and even entire buildings. For example, a traditional house from Bangladesh was set up in the entrance area of the Pinakothek, which served Marina Tabassum as inspiration for her buildings in rural areas. Accompanying the exhibition is the monograph "Marina Tabassum Architecture: My Journey", published by ArchiTangle Verlag, which offers insights into an architectural scene that was completely unknown in the West just a few years ago. This all started to change when the S AM, the Swiss Architecture Museum in Basel, in 2017 organized a show that gave many an insight into current construction activity in Bangladesh. Over 60 architecture projects that had previously been documented by architectural photographer Iwan Baan were showcased under the title “Bengal Stream. The Vibrant Architecture Scene of Bangladesh”. The exhibition was accompanied by the eponymous catalogue published by Christoph Merian Verlag.

The respective exhibitions and books draw the eye to a country with a multifaceted building culture that appears at the same time foreign and familiar to us. A prime example is the “Bengal hut” based on bamboo and air-dried clay, which the English colonial rulers linguistically transformed into the “bungalow” and exported back to their home country. A tradition of bricks and terracotta exists alongside this which makes the brick one of Bangladesh’s typical construction materials. It was used for example to build mosques or the Buddhist and Hinduist monasteries. Today it can still be found in modern buildings – such as the parliament building in Dhaka designed by Louis Kahn, one of the great architectural masterpieces of the 20th century. Its legacy can still be felt in the architecture of Bangladesh, as can that of the works of Muzharul Islam, who brought Kahn to Bangladesh and became one of the most formative figures of local architectural Modernism. In recent decades, some of those he strongly influenced have created a unique architectural scene that oscillates between local tradition and international influences.

This also applies to Marina Tabassum. After studying Architecture at the Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology BUET for ten years she was a partner at architecture practice Urbana, which she had founded in 1995 together with Kashef Mahboob Chowdhury. During this time the two won the competition to design the Independence Monument and the Museum of Independence in Dhaka, which explores the country’s history and its struggle for independence. For the monument they placed a slim, glass-clad tower on a newly designed square. The museum itself was constructed underground, as was a water fountain in the shape of a pillar that commemorates the victims of the 1971 Bangladesh War. The architect explains the concept: “Bangladesh’s independence is a story of duality: It was achieved through selfless sacrifice in a brutal war. Two towers of light define the two events. One stands on the square as a beacon of hope, the other is a column of water that captures the pain of loss. One is not complete without the other.”

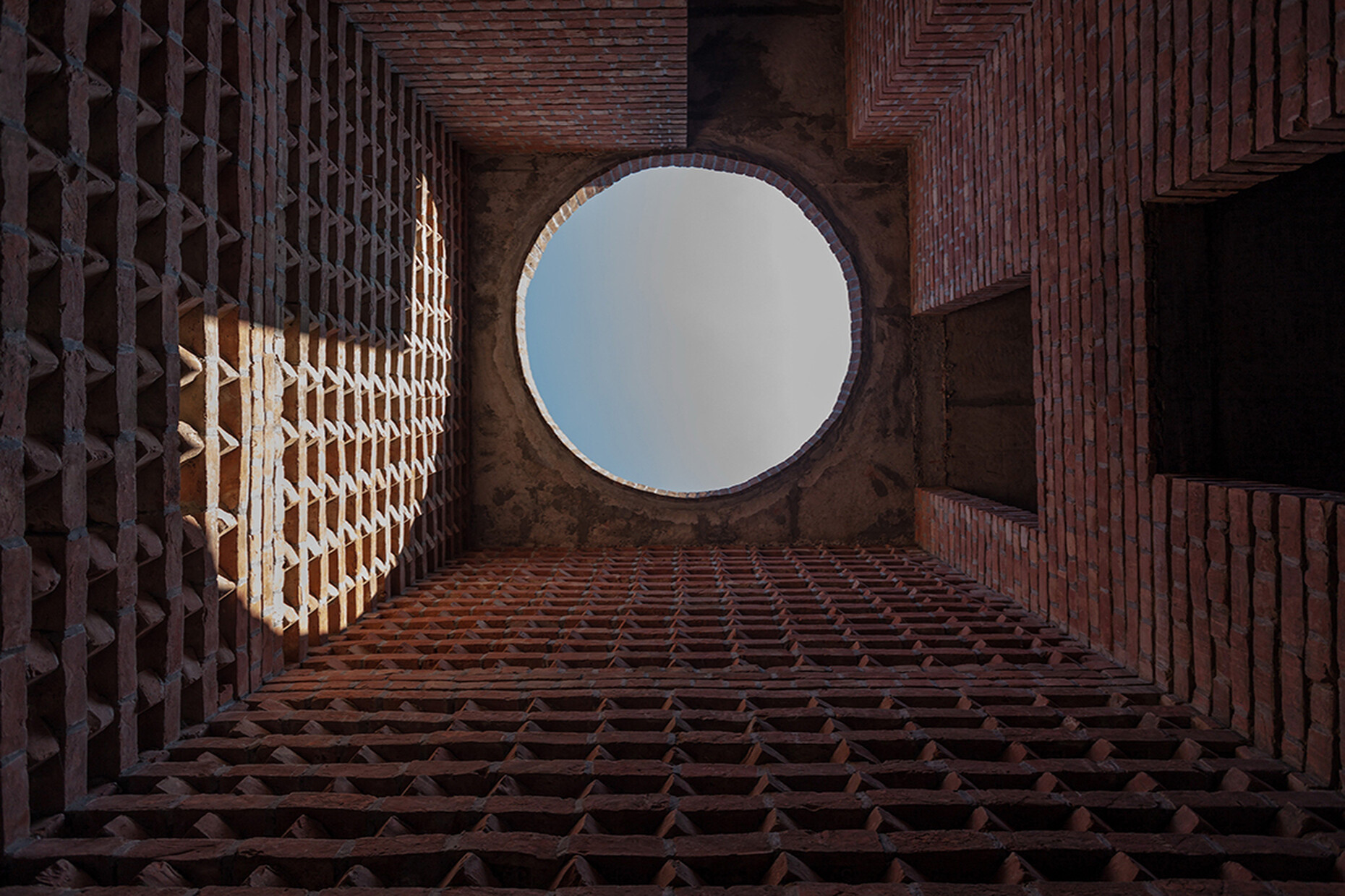

In 2005, Tabassum founded her own studio and among other things realized the above-mentioned Bait Ur Rouf Mosque in Dhaka, probably her best-known work to date. Like other projects of the local architecture scene the building is so fascinating thanks to its focus on space, material, and light. “The mosque is a place of refuge in a dense neighborhood. The clarity of the space, and it obeys no hierarchy, is of crucial importance. Instead of glorifying symbolic elements such as domes and minarets, it seemed right to focus on the spirituality of the space. Light became an important design element,” the architect explains. Seen from the outside, the building resembles a closed cube, which when you step into it dissolves into separate spatial layers. The volume thus entails a circular brick shell, into which in turn a rotated concrete cube is inserted that serves as a prayer hall. Visitors entering from the street gradually enter a place of stillness enclosed by the circular brick sleeve bathed in zenithal light. Above the prayer hall the architect positioned dot-shaped openings reminiscent of the night sky. The probably most poetic moment of the building occurs when the light points created through these openings scatter across the entire space.

In addition to the interplay of light and space, Marina Tabassum also prioritized creating a pleasant indoor climate in the Bait Ur Rouf Mosque. The spatial layers interact with the perforated brick façade and the light wells opening up to the sky to ensure natural ventilation. She consciously eschewed technical solutions in this context: “A building has to be able to breathe without artificial aids. The permeable building shell, open courtyards, and long verandas are brilliant traditions from the time before air-conditioning that continue to be valid today,” she comments. The topic of construction adapted to the regional climate is also to be found in other projects by the architect, such as the AR Tower, an eight-story office building in the west of Dhaka that was completed in 2022. The expressive building, which serves as a landmark of sorts in the heterogenous quarter, has a brick façade that is structured by vertical window fins. Horizontal sunshades and diagonal slats ensure light and shadow alternate over the course of the day. At the same time, together with the adjustable glass openings the fins reduce heat generation inside the building. The Comfort Reverie project, a twelve-story apartment tower also located in Dhaka, follows a similar concept. The rhythmical fins in the brick façade are conceived in such a way that the window openings are protected from the low western sun and air is able to circulate in the building.

However, Marina Tabassum’s buildings can be found not only in Dhaka, but also in rural areas. One example is the Panigram Resort, an eco- and socially conscious tourism project in Jessore completed in 2018. Tabassum engaged with the local traditional architecture to create the design, and the residents of nearby villages were also included in the planning and construction process. “Rural Bangladesh is uniquely beautiful – the soul of the delta world. It felt criminal to me to invade this calm with the noisy din of construction. Panigram offered the opportunity to rediscover the lost pride and the belief in the wisdom of the country that developed over hundreds of years of settlements in the delta,” Marina Tabassum says of the project. The houses and their arrangement draw on the traditional thatched bamboo and mud-walled huts of the region and form courtyards. The traditional thatched roof draws the eye: The architect developed a wooden structure for it that lends it an organic shape. Added to this is a brick-built podium that protects the buildings from flooding.

The engagement with the culture and society of Bangladesh can be seen not lastly in the architect’s social projects geared at improving ecological conditions and the living conditions of the poor. This includes for example the Khudi Bari project, which translates as “tiny house”. It is designed to serve as a shelter for the marginalized landless population who living in the sand flats of the Meghna River – an inexpensive modular living unit that can be built easily and quickly. Like the Panigram Resort, the project is inspired by the traditional architecture of the Ganges Delta and is based on the use of local materials such as bamboo. The usable space of 128 square meters is split across two levels such that inhabitants can withdraw to the upper level in case of floods. The structure on which the project is based is scalable and can thus also be used to construct larger buildings.

Marina Tabassum’s oeuvre, ranging from buildings in highly dense urban areas, or edifices that draw on the traditional building culture in rural areas through to social projects and an exploration of Bangladeshi history, bears witness to the architect’s multifaceted approach. She also often opts for a processual methodology, as is the case in the Panigram Resort, where the local population was involved in the planning. Last but not least, in her buildings she reacts to the tropical climate of her country and the specific interaction of water and land there. In her projects she takes into account the frequent floods that so define the life of the people in rural areas in particular. To this end she devises solutions inspired in equal part by the built culture of Bangladesh and by international influences, and designs buildings that are in harmony with the water. In 2022, the architect won the Lisbon Triennale Millennium bcp Lifetime Achievement Award.

Recommended Reading:

Marina Tabassum Architecture: My Journey

Edited by Cristina Steingräber

Hardcover, 288 pages, language: English

ArchiTangle, 2023

ISBN 978-3-96680-012-9

68 Euro

Bengal Stream – The Vibrant Architecture Scene of Bangladesh

S AM Schweizerisches Architekturmuseum

Niklaus Graber, Andreas Ruby, Viviane Ehrensberger (ed.)

Hardcover, 448 pages, language: English

Christoph Merian Verlag, 2017

ISBN 978-3-85616-843-8

68 Euro