Spotlight on Women Architects – Johanne Nalbach

When the young architect Johanne Nalbach and her husband Gernot Nalbach founded their joint office Nalbach + Nalbach, it soon became clear to them that they couldn't work together, although at first it didn't seem to matter so much. Johanne shared the fate of many of her colleagues in offices run by couples, and she wasn't always able to be present in the studio. Starting a family and raising three children usually comes at the expense of the woman. Continuous work on extensive building projects is often then only possible in parallel, and with a huge amount of effort. So it was really a process of emancipation when, after a few years, she was gradually able to completely take on her own projects and oversee them from beginning to end, from winning a design competition to attending a building's inauguration ceremony.

A glance at the past: Gernot and Johanne studied architecture together in Linz, Austria. He saw her in a lecture during their first semester and introduced himself, and since then they've been a couple. He was bursting with ideas, did everything in a hurry, even got his diploma earlier than she did. She did some modelling on the side, earning good money with it (“I wanted to be beautiful back then”), and worked meticulously, completing everything with honours. Her first project was a small conversion, and her first fee a used surfboard. “My liberation arrived with the computer,” she states succinctly, because from then on she was no longer dependent on her husband. Gernot could draw very well. His designs always looked perfect and so he was able to push projects through. He was dominant, and not particularly interested in working in a cooperative manner. The separation of projects into his and hers was inevitable.

Their joint office remained in existence, however. To this day the projects they work on are done under the name Nalbach + Nalbach Architekten, always with one of the two partner's names in the subheading. Johanne Nalbach has shown particular expertise in the design and construction of hotels. On the basis of successful competition entries she's built hotels in Cologne, Leipzig, Hamburg, Wismar, Seehof (Mecklenburg), and four in Berlin alone, and the buildingsalways have their own aura. In Hamburg's HafenCity, she's created a building that is typical of the local style, with an attractively designed clinker brick façade, which is prevented from being too straightforward through its use of coloured windows and corten steel elements. In Wismar, she was able to master the integration of modern design elements in an old town situation, and she's also successfully designed several buildings for the art'otel group that focus on the combination of art and architecture. And finally, Nalbach + Nalbach have fulfilled a long-held dream with their own wellness hotel at the Neuklostersee lake in Mecklenburg. The property is in an idyllic location, and with its historic stone house, a Kunstscheune (art-barn), Badescheune (bathing barn) and holiday homes, has become an architectural jewel thanks to Johanne Nalbach's renovations and extensions. The family now also run a second resort, a suite hotel at the historic Kavaliershaus manor house at Lake Fincken, which is also in Mecklenburg.

Although Gernot Nalbach has now retired from active office work, Johanne Nalbach is as active as ever. As recently as October 2022, she was able to complete a project that was especially important to her. The Kant-Garagen in Berlin, a cultural monument to the history of mobility that had fallen into obscurity due to neglect and disuse, was to be renovated under the strict conditions of monument protection. A job made in heaven for Johanne Nalbach, who undertook a thorough investigation of the building's history before approaching both the client and monument preservation authorities with her typical verve and tenacity.

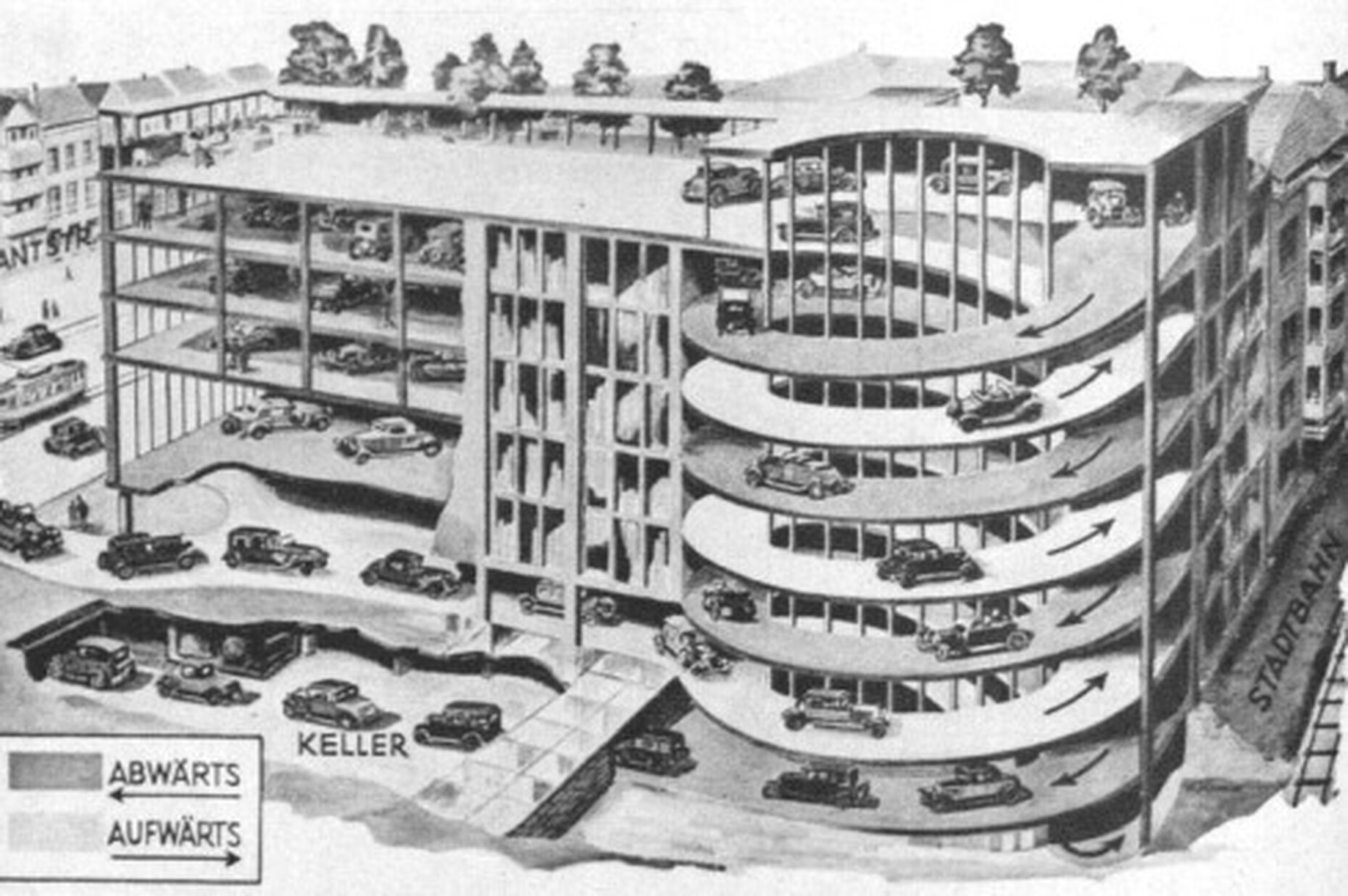

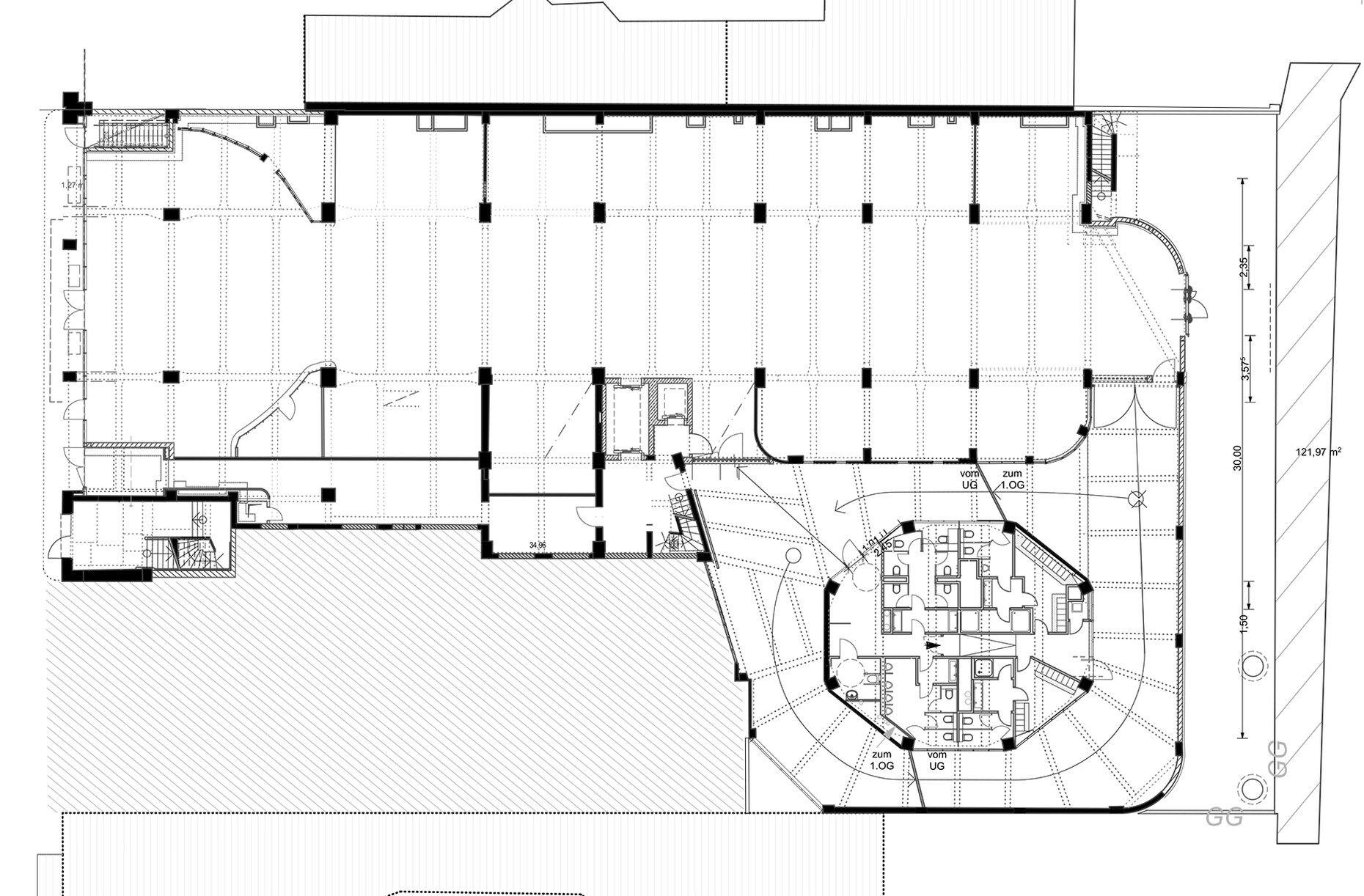

The parking garage, opened in 1930, was commissioned by the engineer Louis Serlin and designed by architects Hermann Zweigenthal and Richard Paulick (a Bauhaus and later GDR architect). All of the building's historical objects, i.e. inscriptions, fittings, building services, the original automatic fire doors and the steel, heated parking “boxes” with their sliding doors, which once housed valuable Horchs, Mercedes and Maybachs, were removed and secured.

The Stilwerk, a concept store focusing on international interior design, is now the main user, making it was possible to preserve the character of the individual storeys to a large extent while also allowing for them to be experienced as former parking areas. 36 of the original boxes have been preserved and are used as offices or showrooms; the double-helix ramp is still accessible and is still drivable when absolutely necessary. The ground floor has a kind of market hall with themed restaurants, and a café is located in an outdoor courtyard. The upper floors have space for retail stores and art exhibitions, with one floor reserved for offices. A luxurious penthouse flat is located on the top floor. The garage's previous owner had wanted to demolish the building because it was allegedly dilapidated, and total reconstruction of the structure was discussed as well. In the end, however, the struggle to preserve this listed structure was well worth it.

The building, with its impressive glass curtain wall and its largely original interior, now presents itself as a radiant beauty, and one wonders how it was possible for this historical icon of mobility to be so grossly neglected in the first place. But the project has also succeeded because Johanne Nalbach built a Stilwerk hotel on the neighbouring property, which is organisationally linked to the garage.

Every architect you talk to will mention how important it is to react to the existing “context” when working on a project. And yet, when it comes to a finished product, this is often not actually recognisable. With Johanne Nalbach's projects, however, this is entirely plausible. Her hotel in Hamburg's HafenCity, for example, is closely related to local design traditions. Not only does its brick façade tie in with the northern German way of creating brick buildings, but its relief structures also invoke the Expressionism of the nearby Kontorhausviertel, without, of course, literally reusing its decorative motifs. For although Johanne Nalbach has become an expert in the preservation of historical monuments as well as building within a historical context, building in an explicitly historicist manner is the last thing she wants to do.

The fact that her office is not designed for constant growth – here she quotes Gustav Peichl, “It's impossible to keep track of more than eight employees” – is due to the fact that she can't delegate, that she works on competition designs herself and that she has a few clients who repeatedly commission her directly. The mixture of her sense of duty, passion and commitment to her work has probably also prevented her from becoming more involved with teaching. She's well aware that she would not be able to manage a chair responsibly in addition to her work in the office, which is a pity, because through her commitment to the profession and didactic skill she is wonderfully able to convey ideas about architecture. And thus she has mainly dealt with individual teaching assignments and adjunct professorships, at both the University of Kansas and University of Kentucky, but most of her teaching is done in Berlin in the form of workshops that are very popular with American students.

Delivering a project on time and within budget is also one of Johanne Nalbach's cardinal virtues, in keeping with her professional ethics. The Federal Press Conference building, for example, which can be seen almost daily on the TV news, is one of the few government buildings whose planning and construction took place without any accompanying publicity. She doesn't like to be in the limelight anyway, much preferring to remain behind the scenes, calmly and quietly discussing issues and convincing people about her ideas.