Spotlight on Women Architects – TOMAS Transformation of Material and Space

David Kasparek: Sofia Ceylan, Katharina Neubauer and Annabelle von Reutern, you have recently begun collaborating as TOMAS. We are sure to hear more about the name in a moment, but first up: How did you all get to know each other?

Sofia Ceylan: We all met up in 2007 while studying in Aachen. We were in the same studio. Katharina and I even sat next to each other for the kick-off event. After graduation, we all moved to Berlin to study on a Master’s program. It was only after completing it that we all branched out in different directions in architecture.

David Kasparek: You’ve worked for various offices, Sofia Ceylan at Kim Nalleweg, Katharina Neubauer at Max Dudler, but also teaching at Berlin Technical University and in Lucerne today, Annabelle von Reutern for Concular. What brought you together again?

Annabelle von Reutern: Age. (laughs) Seriously, I always wanted to freelance and get involved in project development. Now was a good time. It just so happened we were all wanting to change direction at the same time. Katharina suggested we brainstorm on what should happen next and that’s how TOMAS came about.

Katharina Neubauer: We had already considered setting up together straight after our Masters but instead we decided to get some experience working for various offices. Then at some point I asked myself why we had somehow forgotten our original idea. We had worked within fairly rigid structures, something which in my case was interrupted by my taking parental leave. I had a six-month old baby and was sure I didn’t want to return to those male-dominated office structures again. Meeting up in Venice for the final weekend of the last Biennale provided us with the impulse to set up our own office together. And then things really took off and the idea of establishing TOMAS was born.

Sofia Ceylan: Then of course the question was what do we actually want to do. Generally speaking, architecture practices are service providers for investors. Which in itself was a very strong motivation for me to determine who I wanted to be in that process and where we could locate our work.

David Kasparek: Where do you place yourselves and your work on that path spanning investment and the building realized by an architecture practice? Are you the people, who like Annabelle von Reutern said, develop projects or the ones that realize them – or both?

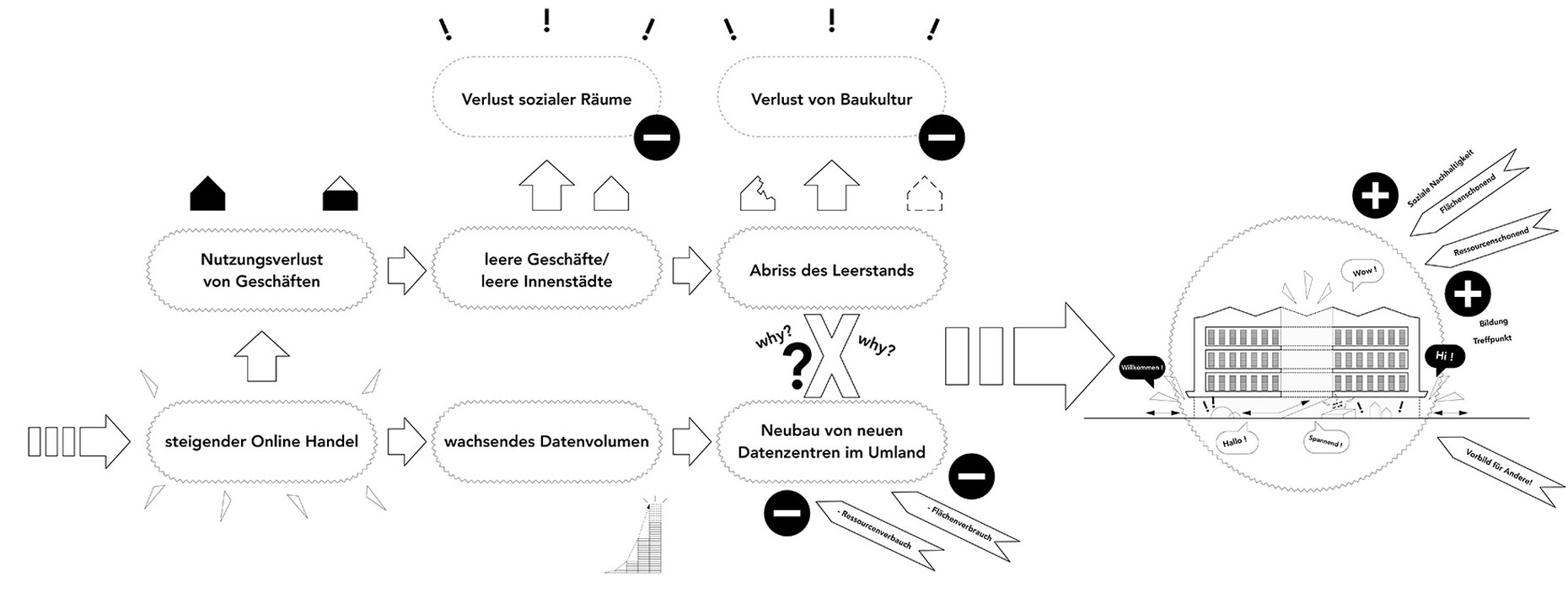

Annabelle von Reutern: TOMAS takes care of everything. When you think about properties, most people don’t consider them over their entire lifecycle, but often only in sections: initial investment, planning, operations, sale. That way you get things nobody is responsible for, gaps. Which is one reason why some properties become dilapidated and don’t get the appreciation they deserve. The building becomes an asset. We are convinced that you can do things differently. We want to close this gap by taking on responsibility. TOMAS wants to invest, transform, and take care of a property’s entire lifecycle. We identify underrated empty buildings and draw up new concepts for their use that were perhaps unusual previously. In other words, we operate as project developers but also work to preserve or upkeep real estate. And because we like sharing our know-how, we also offer the transformation process for underrated buildings as a service for owners who have no idea what to do with their property.

David Kasparek: And what part does social responsibility play in all this?

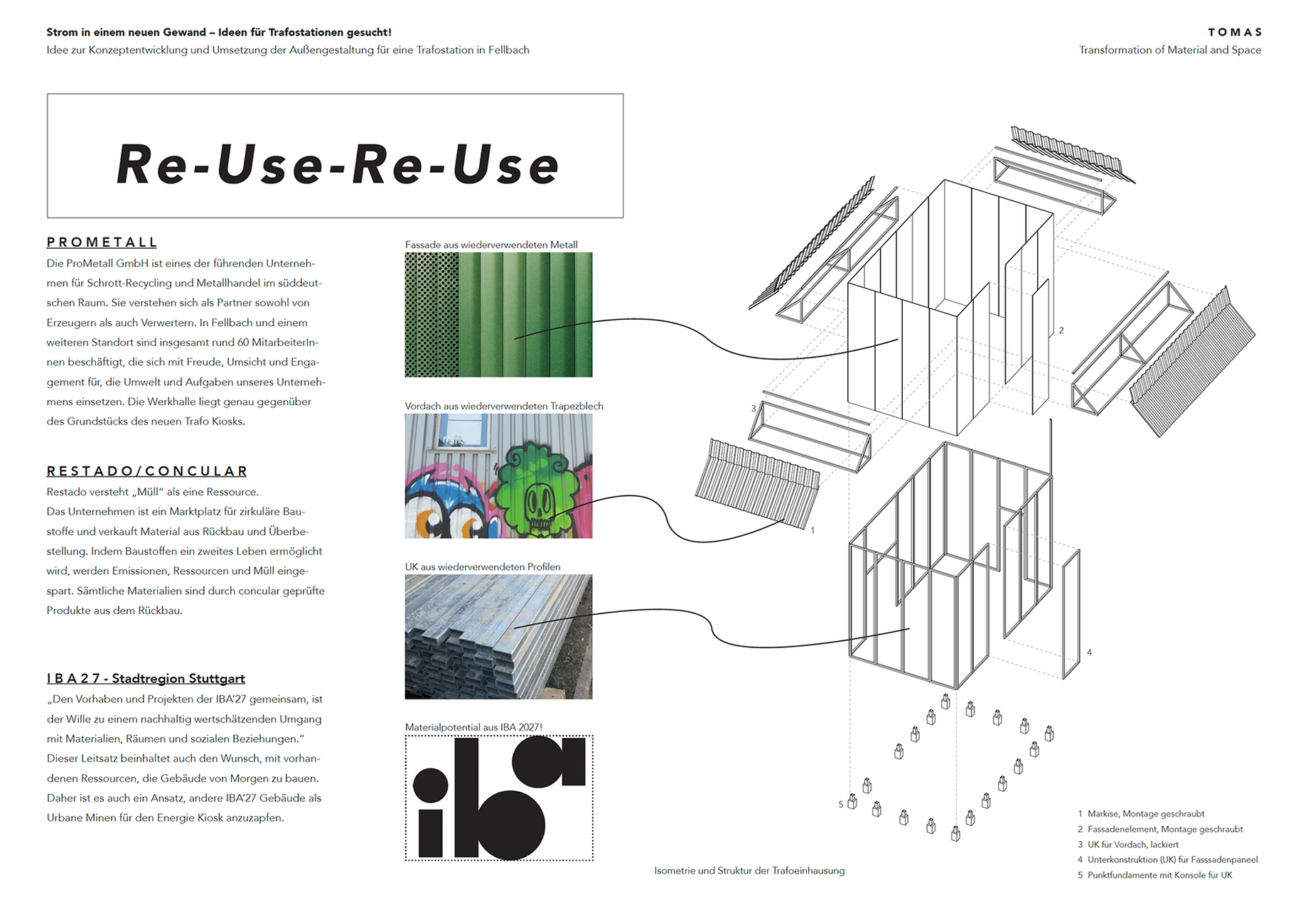

Sofia Ceylan: We aim to achieve our transformation projects without placing an excessive burden on the planet. That means, for example, preserving what already exists, a sparing use of resources and engaging in circular building. Social tensions are directly linked to the nature of buildings. For us social responsibility means more than ensuring rents are affordable, it’s about generating genuine participation from the investors, who can get involved with small financial contributions via the planners through to the users who would not stand a chance in other properties.

David Kasparek: You feature the town hall in Krefeld on your website – a building realized after a design of Egon Eiermann between 1953 and 1956, and which has actually been up for modernization since 2017 – and you had yourselves photographed there. What’s your connection with the building?

Katharina Neubauer: We were looking for an empty building in NRW for a photoshoot and our photographer Magdalena Gruber suggested it.

Sofia Ceylan: It was an excellent demonstration for us of how people have to be repeatedly reminded about buildings and what they have to offer. And it’s not even one of these unpopular, seemingly faceless structures but a building by Eiermann, though completely run down and with an uncertain future. There are even people in favor of demolishing it. That’s precisely the kind of thing we have to deal with today. How many times have we been asked about the Eiermann building now? (looks at the others) In this case, the first step has worked, namely getting attention for the property.

David Kasparek: As regards a building by Egon Eiermann it’s easy to find arguments for its preservation and keeping it as part of our built cultural heritage, but what about buildings whose reputation is not as good?

Annabelle von Reutern: It’s important to draw attention to these properties, to buildings that are underrated and regarded as worthless by many people. That’s why we have a special interest in abandoned department stores or churches, or railway buildings that have not seen any use for a very long time. We have a preference for buildings from the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s, which are all-too-often referred to as eyesores.

Sofia Ceylan: I come from Duisburg. There are a lot of empty properties there, and that includes apartments, yet at the same time rental prices in Düsseldorf are skyrocketing. So you have an absolute disparity in what is roughly the same area. And simultaneously, terms like "junk properties" are bandied about, suggesting the buildings are rubbish and can no longer be put to any use. A "junk property" is no longer an asset and has a negative impact on the street or the entire quarter. That is also part of TOMAS’ mission: We want to look at how an affordable rental price is achieved. Where is there leverage? Well, in the initial investment by focusing on properties that nobody wants anymore ...

Katharina Neubauer: … and by presenting what might initially seem like unusual usages, like in Celle, where we proposed converting a disused department store to a data storage building. Annabelle got it down to a tee: Sometimes you have unusual typologies and then there is always this underlying question of whether residential is really the best use for the typology.

”The crucial point is being able to help shape things. But if we only have a 20 percent stake then we also only have a 20 percent chance of determining things – that’s what we want to change.“

All of this also relates to the topic of climate justice. Anyone looking at your website is struck by another area of justice, namely, gender equality. For one thing you criticize the fact that construction squanders material resources and is responsible for eating up space and generating waste, and you are also very vocal in highlighting the inequality between men and women: while 80 percent of land worldwide is in the hands of men, only two percent of global risk capital goes to women. So is the name TOMAS an acronym, or a reference to the Thomas cycle, according to which there are fewer women than men on boards in German companies?

Katharina Neubauer: It’s a backronym. TOMAS existed first– because of the unequal distribution you just mentioned – and then the meaning of the individual words.

Annabelle von Reutern: If there are more Thomases (men) on the boards of DAX companies than women then evidently you need to be a Thomas to be successful.

Katharina Neubauer: What’s more, we weren’t aware just how drastic some of the figures were that we got together. If 80 percent of the world’s land is owned by men, then they also decide what happens to it. That definitely needs to be highlighted and in the very best case – and this is our long-term goal. That figure will alter somewhat because we enable other women to join forces and buy a property.

Sofia Ceylan: The decisive point is being involved in shaping things. If we only have a 20 percent stake, then we only have a 20 percent chance to help shape things – and, as we said, we want to alter that. That’s why we want to encourage women to engage with this topic. That begins with the wording: "asset", until now I saw this as the extent of my work as an architect. From the outside, this entire real estate industry always seemed so unfathomable. For us it’s also about breaking through the divide between architecture and the property industry.

David Kasparek: I would surmise that neither climate justice nor gender equality played a very big role in your training …

Annabelle von Reutern: … zilch, zero!

Sofia Ceylan: Mies Van der Rohe, Le Corbusier and all the other boys …

Annabelle von Reutern: It was restricted to them. And lecturers spoke disparagingly about Zaha Hadid. How dare a woman be successful and on top of that behave “like a man”!

Katharina Neubauer: Yes and no. Naturally, we did have certain influences. Like Anne-Julchen Bernhardt who supervised the dissertations for both our Bachelor and Master’s degrees. So there were a few exceptions, but sadly they were just that.

David Kasparek: So how did you become acquainted with these topics?

Annabelle von Reutern: It’s enough to be a woman and to come up against boundaries that no man would have to deal with. And presumably there’s no need for me to explain how we encountered the subject of climate justice. It’s more a question of our wondering how people can not care what consequences their own actions and behavior will have.

Sofia Ceylan: Although this is 2024 and we are three women engineers who studied at leading universities and operate in a privileged environment there is a gender-pay-gap. There are men among my circle of friends who own a property or have already launched their third start-up. That’s no coincidence. And in this context, you need to talk about your own doubts and how you address them. Should I give up an open-ended contract to set up a business? What about family planning or providing myself with an old-age pension? Why do I need to ask these questions, and why is it that my male friends don’t seem to share my worries as intensely as I do?

Annabelle von Reutern: The more I explored the topics of patriarchy and capitalism the more angry I got. Today, I understand the system that underpins the exploitation of our planet but also of many people. This anger drives me on and I channel it into something positive. I don’t want to be against something but for something: for a world with more social justice. For a world in which not only the old white man has the right to interpret things but a diverse democratic society.

David Kasparek: OK, then let’s get down to the specifics: What are you working on at the moment?

Annabelle von Reutern: Well, we’re soon going to be looking at a railway building that has been empty for ten years. It’s absolutely crazy that this property in a great location should remain unused. We want to persuade the owner to sell us the building for a good price. At the moment the asking price is much too high. It’s pure speculation. Another option would be to discuss an interim usage with him. We know that the community has a great desire to revive this property.

Katharina Neubauer: We are also considering buying a residential building dating from 1959. Magnificent architecture – a lot achieved with little. But the house is showing its age and the family that owns it would like to sell it. It would be a classic modernization project offering the option of extending the top and ground floor.

David Kasparek: That sounds like a great deal of effort on your part and not like invited, open competitions or peer review evaluation processes So how do you acquire the projects?

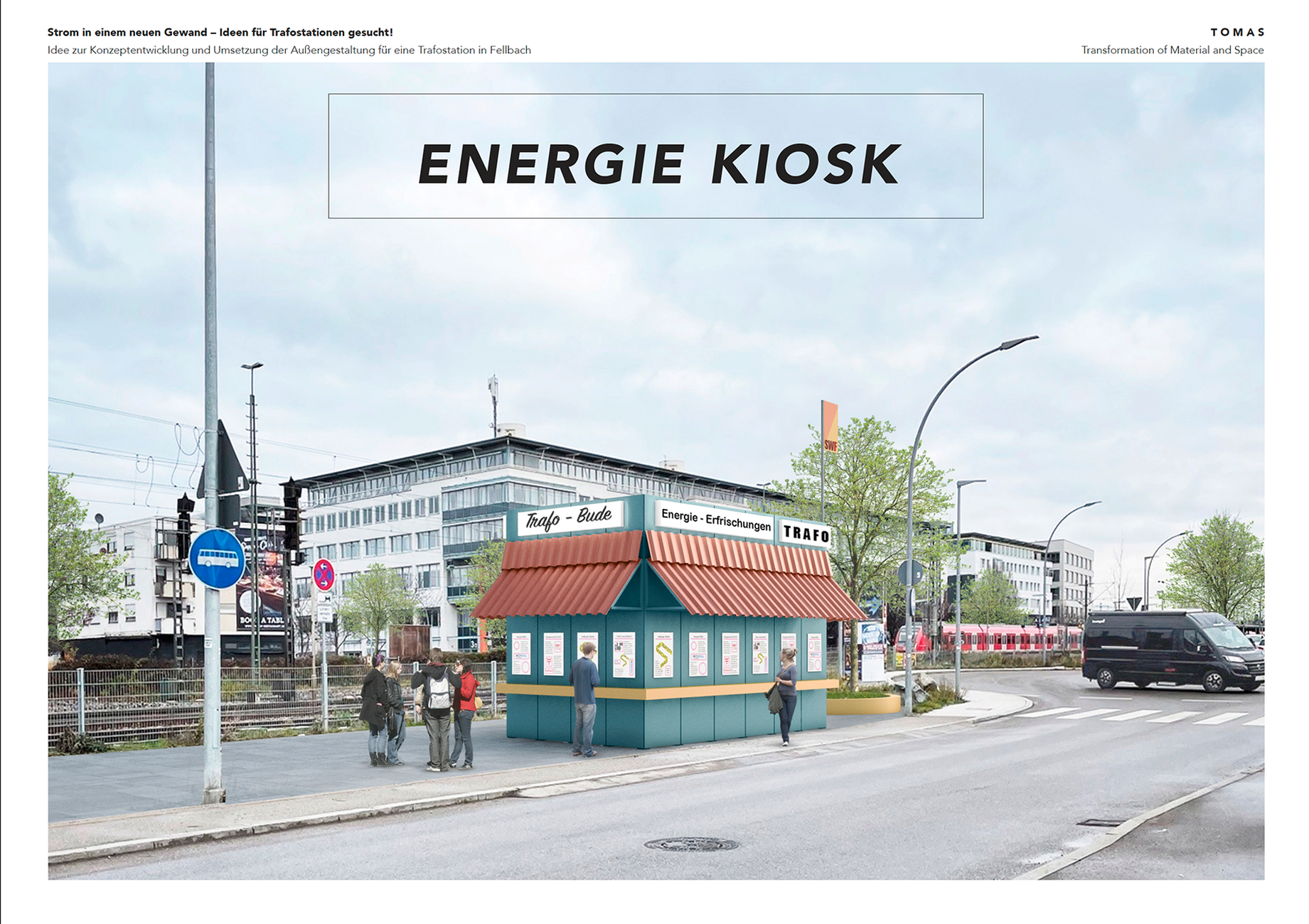

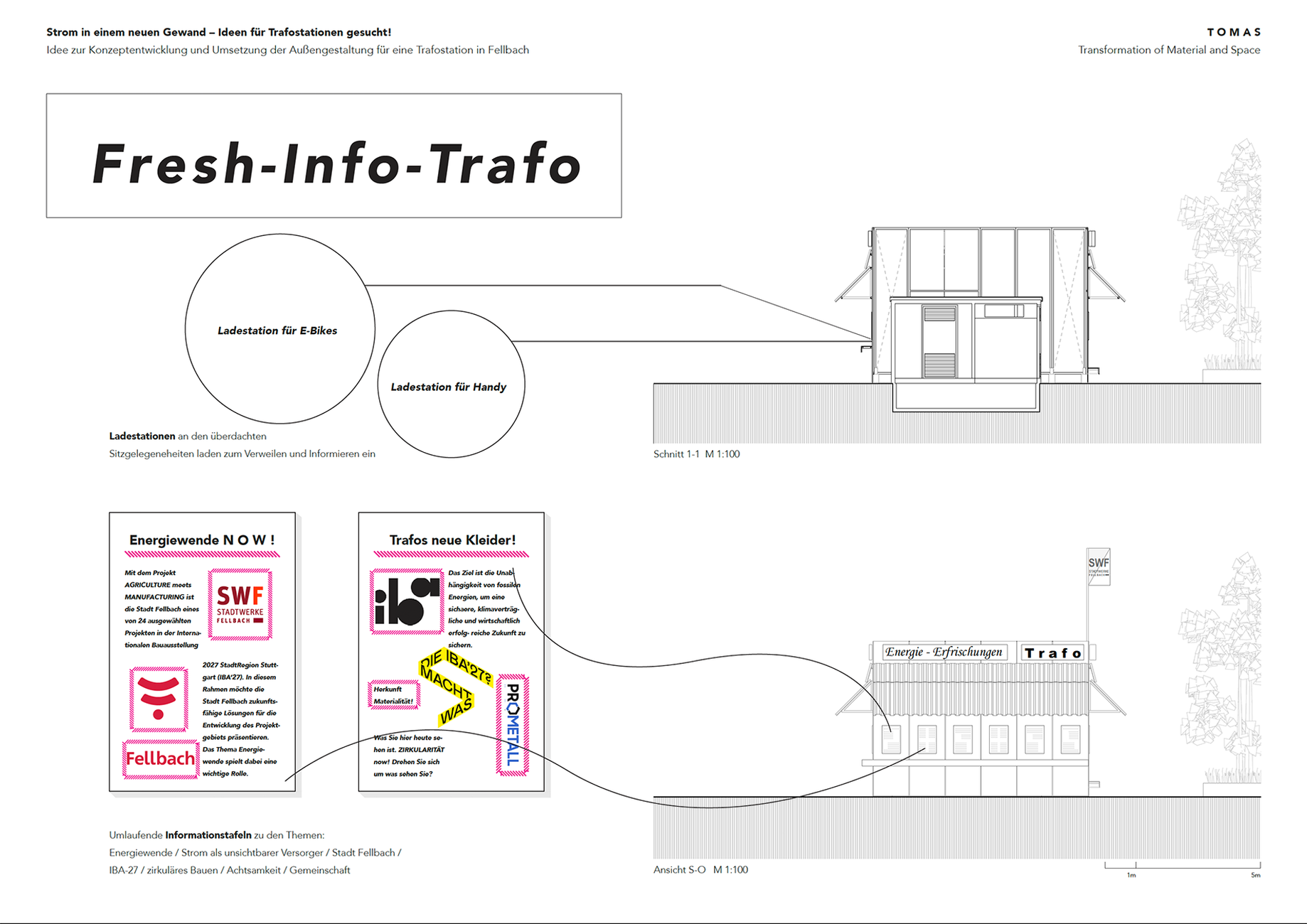

Annabelle von Reutern: Thanks to our experience as architects, we’ve built up a broad network on which we can now draw. We found out about the two objects we just mentioned from this network, something that is a real strength for us as we don’t have to start from scratch. And it has always been one of our core values to take the initiative. If we want something then we go for it. But we have also already taken part in two competitions. And we even received a distinction for one of those.

Sofia Ceylan: There is a huge need for existing buildings to be converted. I recently attended a meeting for district development and got talking to a district manager of a municipal housing association. She told me that they need help in developing their existing properties. This is exactly the kind of thing we want to support.

Katharina Neubauer: And then of course you get enquiries from friends and acquaintances. For example, we are helping with the conversion of an empty three-sided farmyard in Brandenburg. By our intervention we can prevent small properties from falling into disrepair or being demolished.

”Sometimes you have unusual typologies and then there is always this underlying question of whether residential is really the best use for the typology.“

David Kasparek: If you could think of a project that you were able to realize from start to finish, what would that be?

Sofia Ceylan: If I could choose, then I would opt for the Karstadt building in Celle …

David Kasparek: … at the beginning of the year the ideas competition that has already been mentioned several times invited entrants to submit ideas for repurposing and converting the department store in Celle, a city in Lower Saxony. Your entry received an honorary distinction. What was your proposal?

Katharina Neubauer: We proposed using the now empty Karstadt building as a data center. In a way it’s the fusion of my PhD thesis which addressed data storage buildings at the interface between their social significance and the absence of a spatial presence – and the previously mentioned questions about how to deal with typologies like department stores, railway stations or churches. It needn’t always be residential and isn’t always feasible anyhow. But what might a suitable use for this typology be? In this instance, it’s the storage of data, which are the commodities of our time.

Sofia Ceylan: Working on it was incredibly exciting at so many levels. How do you handle such a large structure from the 1970s in such a setting? Which actors are involved? As a half-timbered city Celle is looking for ways of supplying these buildings with sustainable sources of energy without the modernization work ruining their appearance. Our concept uses the waste heat from the servers, which are needed for data storage, heat that occurs naturally. TOMAS always takes an interest in political issues. At the awards ceremony someone told us she was delighted about the conversion concepts, because they take the wind out of the AfD’s sails. The party is calling for the old Karstadt building to be demolished and a new historicizing building to be realized in its place. It was great to see how many people are keen to have the building converted and integrated into its surroundings rather than tearing it down.

David Kasparek: Finally, I’m interested in the question of aesthetics. Not in the conventional sense of beauty but rather with a view to sensuality or meaningfulness. Sandra Meireis and Daniel Martin Feige recently published an anthology that attempts to outline aesthetics purely from the perspective of architecture. In your opinion, does the twofold architectural turnaround that you seem to have in mind also go hand in hand with a different aesthetic? Does architecture that draws solely on the urbane mine look different than it did previously? And should it look different to express its perhaps altered meaningfulness with a different sensuality?

Sofia Ceylan: Yes, I think so. The basic principle of circular building and bio-based-architecture is never at odds with design and the goal of producing something beautiful. For example, one aspect of sustainable building is being able to disassemble it, so it requires different kinds of joints. That is a fundamental topic of architecture. The way that I join something together alters the design. I’m not a great fan of this ostentatious, patchwork-like architecture, which is currently being realized repeatedly in the name of the building turnaround. By contrast, the TU Braunschweig student house by Gustav Düsing and Max Hacke can be completely dismantled, is sustainable and modular. Its design is based on these principles and produces a certain appearance.

Katharina Neubauer: I come across it in teaching: You really have to take a very differentiated view of the aesthetics of our time, which is produced by processes that purport to be or actually are different. As regards participatory design processes or spaces that are dealt with in a processual way I do believe that they can look different, but that doesn’t mean they should be considered inferior in terms of aesthetics. The fact that they look different is not the result of a fad, but stems from a fundamentally different approach to creating space.

Annabelle von Reutern: The question of aesthetics is also about justification. Who decides what is considered beautiful? Like so many people, Sofia and I watched the opening ceremony of the Olympic Games. And now racists, anti-feminists and people hostile to the queer movement are getting upset because the show didn’t fit in with how they see the world. A group of people who previously set the tone are realizing that their influence is waning. One reason we were so enthusiastic about the event is because it was diverse and showed us what a world could be like. It’s essential that we can endure things even if we don’t find them beautiful but without having to devalue these things for being different. I consider it important in all areas of life – including building culture to accept that there my idea of what constitutes beauty is not unique. For me things are beautiful if they don’t overtax the planet and nobody needs to suffer because of them.