Spotlight on Women Architects – Xu Tiantian

The Chinese construction boom of recent decades has, in the eyes of the West, mainly resulted in megacities built from the ground up as well as spectacular architecture designed by star architects. High-rise buildings such as the CCTV headquarters in Beijing by OMA or cities such as Shenzhen, which has grown from a small town of 30,000 inhabitants in the 1970s to a megacity with around 18 million people, are exemplary of high-speed urbanisation in action. Many architectural traditions seem to have fallen victim to this massive upheaval. There are exceptions, however, such as the Chinese architect and Pritzker Prize winner Wang Shu, whose buildings reflect the history of their location. For his Ningbo History Museum in Ningbo, China, completed in 2007, he used rubble from over 30 demolished villages to commemorate lost cultural landscapes. Another example is the work of Beijing architect Xu Tiantian, who aims to strengthen rural structures with the projects she works on with her office DNA Design And Architecture.

Born in 1975 in Fujian, a province in south-east China, Xu Tiantian cites growing up in her family's traditional house as a formative influence on her understanding of architecture. More than 100 people lived in her compound, which had a series of courtyards and corridors. During her childhood and adolescent years Xu experienced China's wave of modernisation, which began in the late 1970s under Deng Xiaoping. The massive urban transformation that started in the 1990s also affected her home, as traditional urban structures were often turned into high-rise housing estates. Xu first studied architecture at Tsinghua University in Beijing and then completed a master's degree in urban planning at the Harvard Graduate School of Design. After gaining work experience in Boston and at OMA, she returned to China and founded her office DNA Design And Architecture in 2004, at the height of the Chinese construction boom.

Xu can now boast an impressive number of buildings. Most of them are located in the Songyang mountain region, a rural area with around 400 villages located 400 kilometres southeast of Shanghai. In recent years she has worked on several new buildings and conversions there as part of the provincial government's various revitalisation programmes. One of the aims of these measures is to strengthen the local economy and support traditional crafts and tourism. Architecture also plays a role in this, but it is not presented as a Western-style spectacle. Instead, Xu makes subtle interventions that she develops together with local residents. She describes her projects as “architectural acupuncture”, the aim of which is to promote the region's cultural heritage. She uses local materials and traditional construction methods, coupled with a focus on communal space. By espousing regional themes and the history of a respective location, she aims to increase identification with the projects.

At the same time, Xu uses architecture to integrate economic and social aspects in order to promote sustainable development in the region. The buildings are intended to strengthen the village communities and help prevent a rural exodus. Her work started with a hotel project that brought her into contact with local residents. This led to collaborative efforts with various villages, for which Xu increasingly became a consultant. Over the years she has designed and constructed prestigious buildings such as museums, but also bridges, pavilions, guest houses and factory buildings that oscillate between regional tradition and poetic modernity.

One example is the renovation and extension of a stone bridge from the 1950s that connects the two villages of Shimen and Shimenyu. To this end, Xu Tiantian designed a wooden roof with a tree-lined open space in the centre. The bridge serves not only as an infrastructural necessity, but also as a place of exchange where the people who live in both villages can meet. At the same time, the design refers to traditional Chinese wind and rain bridges that typically have pavilions to provide shelter from the weather. The theme of coming together characterises many projects in Songyang – such as the bamboo theatre that Xu designed for the village of Hengkeng. Here, an open-air stage is crowned by a bamboo dome that appears to grow out of the surrounding woods. Xu was inspired by a scroll created by the 16th century painter Qiu Ying when considering the theatre's shape and construction. Another example of the Xu's use of traditional building materials are the bamboo pavilions built in the Damushan tea plantation region, which were also the architect's first project in Songyang. Built in a variety of sizes at the edge of the tea plantations, they frame the cultural landscape and can be used for events or simply serve as a vantage point.

In addition to these infrastructural interventions, Xu Tiantian also designs industrial buildings in Songyang – such as a factory located at the transition between the sugar cane fields and the village of Xing. The new complex of buildings is not only intended to be used for the production of brown sugar, but also as a tourist destination and place for the villagers to meet. It has a correspondingly prestigious appearance and looks more like a museum than a factory. Its large glass façade lends the building a modern elegance while offering a clear view of the surrounding fields. At the same time it contrasts with the raw steel frame clad in corrugated sheet metal that encases the main room, which contains the ovens needed for sugar production. Added to this are brick walls, which are sometimes simple and sometimes ornamental, reflecting the dialectic of utilisation at the factory. Xu's tofu factory in Caizhai follows a similar approach, in which the village's traditional tofu production is now run commercially by its residents in accordance with hygiene regulations. The wooden building, which the architect integrated into the existing topography as connected pavilions with shed roofs, also serves as a tourist destination. Its open structure allows people on the outside to view the processes going on inside. A concrete staircase also runs the entire length of the building, further integrating the complex into the landscape.

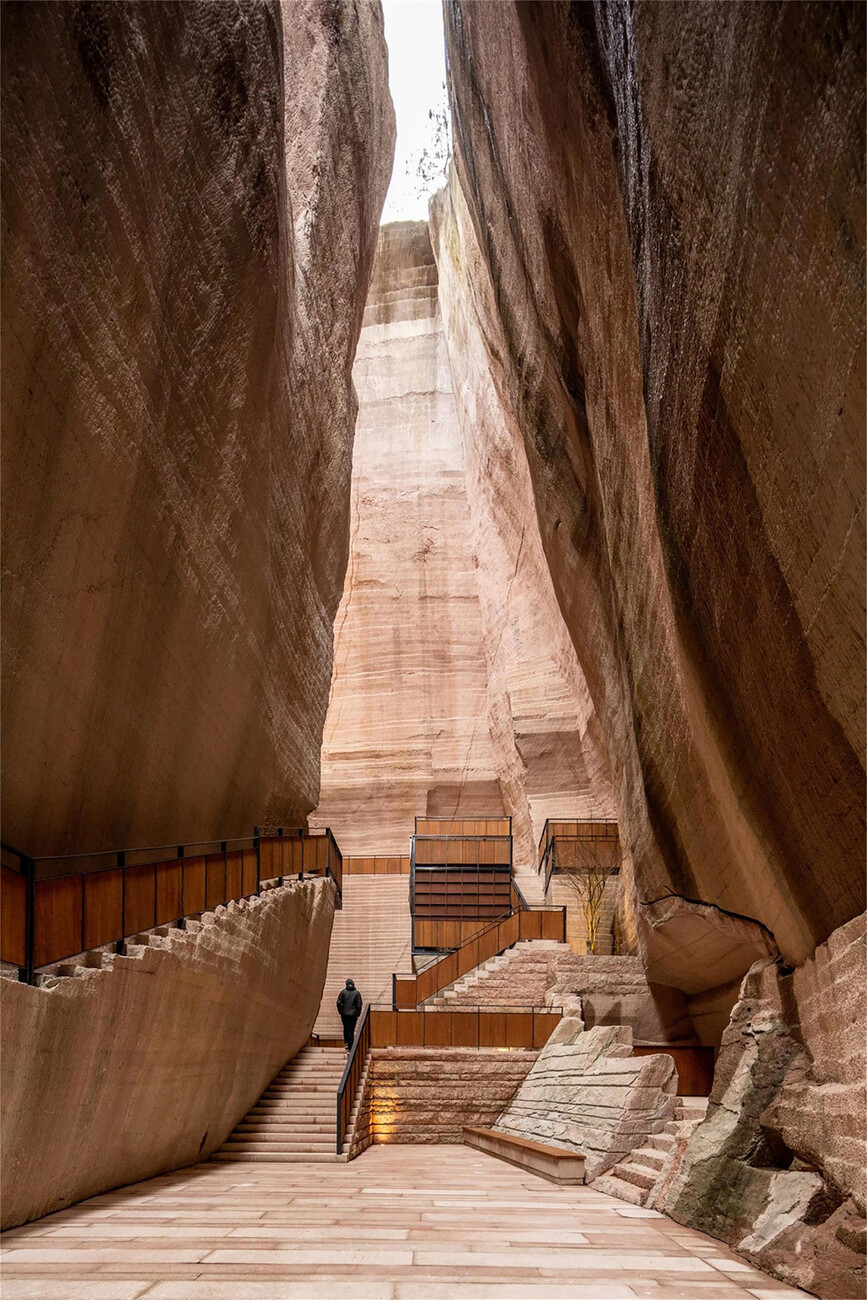

One of the architect's latest projects has proven to be one of her most impressive, although it is not located in Songyang, but in the nearby former mining region of Jinyun. Here, Xu has transformed three quarries in the Xiandu Valley into an open-air library, a meeting place and a stage for opera performances. The architectural intervention itself is restrained, complementing the impressive rock formations. The library consists of a filigree steel structure lined with bamboo, which extends over the stone backdrop in the form of stairs and galleries. What appears modest and simple required a great deal of effort, as the up to 38-metre-high, human-made cavities in these tufa mountains had to be elaborately stabilised with concrete in places.

Further conversions are planned for the more than 3,000 quarries in the region, including a restaurant and a place for tea ceremonies. In contrast to her much more modest “acupunctural” interventions in Songyang, the quarries present themselves as an architectural spectacle in which the architect nevertheless emphasises what is already there. Her work with the layers of stone in the former quarries is a perfect expression of Xu Tiantian's exploration of place and time.