Solid goals

Construction often begins on a small scale. Many architects around the world start their careers with simple, temporary structures that then lead to further commissions and grow a one- or two-person office into a company. SO-IL, founded in 2008 by Florian Idenburg and Jing Liu in New York, has followed precisely this path and is now considered an influential architectural firm in the United States and beyond. Above all, it is their attitude to architecture as something multi-layered and profound that sets the two architects apart from other firms and has enabled them to realize some of the most interesting buildings in recent years.

Florian Idenburg completed his studies in his native Netherlands at the Technical University of Delft in 2000 and then worked for seven years for SANAA (Sejima And Nishizawa And Associates) in Tokyo. During this time, he was able to play a leading role in the creation of the Glass Pavilion for the Toledo Museum of Art in Ohio and the New Museum of Contemporary Art in New York, among other projects. These experiences had a significant influence on his attitude towards architecture, and this influence can also be felt in the projects that he later worked on together with Jing Liu. An interest in the right spatial program, the importance of openness, fluidity, clarity and complexity in architecture can still be felt in each of their projects today. Jing Liu, for her part, has Chinese roots. She left China in 1999 for New Orleans, where she studied architecture at Tulane University. She worked for the renowned architecture firm Kohn Pederson Fox, among others, and also spent some time in Tokyo, where she met Idenburg. In 2008, Liu and Idenburg were able to set up their own office, which they located in Jing Liu's city of choice. She moved to New York as early as 2004, and today she is also very involved in academic work: she is a faculty member at the Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation at Columbia University, has taught at Syracuse University, School of Architecture and is an active board member of the Van Alen Institute.

SO-IL started out in one of the USA's biggest economic crises and saw these uncertain times as an opportunity: “The work in the period following the 2008 financial crisis influenced the first years of our office. It taught us to approach architecture with ingenuity and humility and to see constraints not as limitations but as opportunities for creativity. When budgets are tight, you have to strip a project down to its essence. While it would be easier to work in a more forgiving economic climate, the discipline we have developed has given our work a clarity and focus that might not otherwise have emerged. But after nearly two decades in practice, we know that we need to maximize value and optimize resources at every point in every project. The discussion should actually be about what these values are. What are we striving for together? It's not about the economy, but about how we choose to live.”

So it's about a form of cultural design, especially with difficult framework conditions. This is also expressed in the name of the office, the meaning of which is just as difficult to define as the term culture itself. SO stands for “Solid Objectives” and basically describes the goals of Idenburg and Liu, which they not only think and discuss, but also want to implement in a very concrete way. “Solid” is therefore not to be translated as firm or solid. The office understands it rather as the concretization and solidification of their own ideas and concepts.

Even their first realizations reflect this dichotomy between modesty and the claim that their buildings have an impact on society. The experimental pavilion “Flockr” in Beijing is a temporary structure, but one that is already exploring how social interactions and spatial dynamics can interact. It laid the foundation for their experimental and innovative approach to materials. The temporary installation “Pole Dance” for MOMA PS1 was also light, mobile and designed for interaction: a coherent system of movable poles connected by nets that can be changed by human activity but also by the weather.

Idenburg and Liu achieved their first breakthrough with the construction of the “Kukje Gallery – K3” in Seoul, South Korea, in 2012. A classic cube as a gallery would have been too banal for the historical context, so the entire development was transferred to the outside and wrapped in an artistically crafted metal mesh. The result was an architecture that interacts with its surroundings and allows full focus on art inside. This type of shell with small-scale elements can be found again and again in SO-IL's more recent projects. Facades are never conceived as large-scale, monotonous structures, but always as a composition of small elements that are perceived as unified from a distance, but become increasingly differentiated and detailed the closer the viewer gets to the building. Further projects in the museum sector will follow, such as the Jan Shrem and Maria Manetti Shrem Museum of Art in the USA or the Amant Art Campus in New York. The relationship between people and (public) space is a recurring theme.

Their approach to the so-called “double loaded corridor” also shows how seriously they take this. This is a corridor that provides access to spatial units on both of its long sides and is therefore rarely or never supplied with daylight. This highly efficient way of organizing a building is a common practice in high-rise construction. But SO-IL criticizes it sharply and says: “The problem with most ‘double loaded corridors’ is that they are reduced to their most efficient and banal form - dark, narrow and lifeless. It is possible to transform them into meaningful spaces through good design. But why not explore completely new typologies that offer more permeability and connection, both within the building and with the city as a whole? In 450 Warren, for example, we completely challenged the assumption of a central corridor and created a circulation system that allows for air and greenery, transforming the path from street to apartment into a vibrant experience of joy and connection.”

In fact, the “450 Warren” project is an example of how apartments can be naturally lit on three sides through a clever arrangement of building masses and sophisticated access systems with balconies, paths and terraces. The spatial qualities of the individual residential units are significantly enhanced as a result, and at the same time additional living and communication zones are created, which can be interpreted as spaces for appropriation by the residents. The access corridor becomes a multifunctional spatial structure that, on the one hand, characterizes the building in terms of design and, on the other hand, is intended to have a positive effect on community life within the building. The traffic area becomes a public space.

This is also the starting point for the title of the new book, which Idenburg himself describes as follows: “‘In Depth’ reflects a dual ambition. On the one hand, it summarizes our interest in spatial depth – not only as a physical dimension, but also as a way of creating multi-layered and multifaceted experiences. On the other hand, it refers to the intellectual depth that we strive for in our work, in which we see architecture as a way to examine larger social questions about how we live together. The book addresses housing, density, and the intersections of public and private space, and focuses on creating spaces that foster engagement and complexity rather than simplicity and uniformity. The title also suggests a certain resistance to the flattening tendencies of contemporary design culture—an insistence that architecture should cultivate ambiguity, nuance, and richness.

Indeed, the new apartment buildings in New York combine everything that SO-IL has tested in previous years in various projects for apartments, museums, or installations. In connection with their complex approach to architecture, Idenburg and Liu develop buildings that appear to be quite well-integrated into the urban fabric from a distance, but become more interesting and different with each step, just like “450 Warren”: on the outside, this ensemble of three buildings appears calm and clearly structured, with large openings in the façade for windows and loggias. The exciting part is the intricate façade made of twisted, gray brickwork within the structure. Three separate buildings form two courtyards and were connected by meandering access balconies made of exposed concrete. Story-high cable nets serve as fall protection and create a separate world within the ensemble.

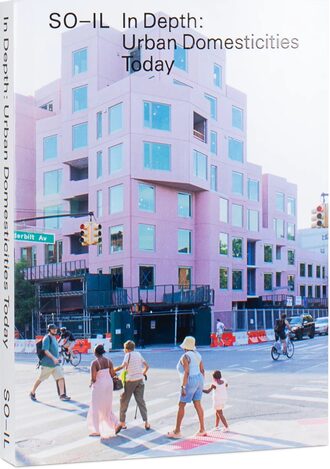

Meanwhile, in another part of New York, the Vanderbilt residential building is nearing completion. The design offers a variety of communal outdoor spaces that encourage shared activities in different sizes and shapes. A leafy backyard enhances the local streetscape, while a central courtyard is brought to life by the movement in the surrounding area. An elevated public square also provides a visible community area that connects indoor and outdoor spaces. The residential units are designed so that residents can participate in several environments at the same time. Each apartment has access to both the lively street front and the quieter interior of the site, as well as to shared outdoor areas within the building. Not only are the apartments organized in interlocking fashion across different levels, but the courtyards, balconies and terraces also permeate the building and become part of a structure that can be used communally.

In fact, the two residential buildings described above look like small, self-contained towns. According to Idenburg, this is also one of the differences between American and European residential construction: “In the US, living in a building is more like living in a hotel, with all the amenities and a doorman. This creates a ‘culture’ for each building – a brand, a style, a shared form of entertainment. Often, the building's caretaker or concierge is the heart of the residential community. Furthermore, at least in New York, the cooperative model is still strongly represented. This makes a US building more like a cruise ship, while in Europe the residential building is more part of the overall urban fabric. So maybe there is more diversity in Europe in terms of typology, but in the US there are more vibrant micro-community models in terms of organization.”

If SO-IL's models for residential construction are successful, they will have a lasting effect on the way we build and, consequently, live in the US. Idenburg is firmly convinced that fundamental changes must be made in our approach to building so that the mistakes of the past are not repeated: “We need to shift the conversation from efficiency to quality of life. Housing must take into account the diversity of human life – both in terms of who occupies these spaces and how they are occupied. This means creating adaptable frameworks that continue to evolve and incorporate social and environmental considerations from the outset. We also need to think of homes as civic infrastructure, with thresholds, courtyards and shared spaces that invite exchange. Perhaps most importantly, architects need to advocate for design that prioritizes the long-term health of communities over short-term gains. This means breaking the 30-year development cycles that drive perpetual urban renewal until the planet's resources are fully depleted. If we leave this to the market, little will change. Consumer choice won't change this because the dominance of this one, market-driven type wipes out the collective knowledge of architectural alternatives.”

In Depth

Urban Domesticities Today

Edited by Florian Idenburg, Jing Liu

With photographs by Iwan Baan, Naho Kubota

With contributions by Ted Baab, Florian Idenburg, Karilyn Johanesen, Nicolas Kemper, Jing Liu

Design: Geoff Han

Lars Müller Publishers

2025

17,0 x 2,5 x 24,0 cm

Language: English

ISBN: 978-3-03778-757-1