A New Manhattan for Amsterdam

Boasting an average of 11,000 new residents per year, Amsterdam is growing. Because its downtown is neither pretty nor historically important, and rather, more than anything else, heavily developed, the principal direction for the city’s expansion since the 1990s has been to the north and east. These areas were once home to industry for the Port of Amsterdam and plans to transform them into lively residential districts have existed since the 1960s. However, it has only been recent population growth that has lent these proposals the necessary momentum. Since that time, it would seem that new islands are being developed into new residential districts almost by the year; there is Java-eiland, Borneo-eiland, Sporenburg, and Cruquis-eiland. They are all already so heavily developed one could be forgiven thinking things had always been that way. Now, the urban developers have come a few kilometers further east, directly to the shores of the Ijmeer, where a huge dam once separated the Dutch from the North Sea. And because there are no former port islands left to be converted, new islands have been created by sandfill, islands scheduled for development into residential areas right up until the year 2040. One such island is Zeeburgereiland, created by means of a sand-and-stone fill at the beginning of the 20th century. It now stands in the water like an arrowhead, pointing in a northwesterly direction.

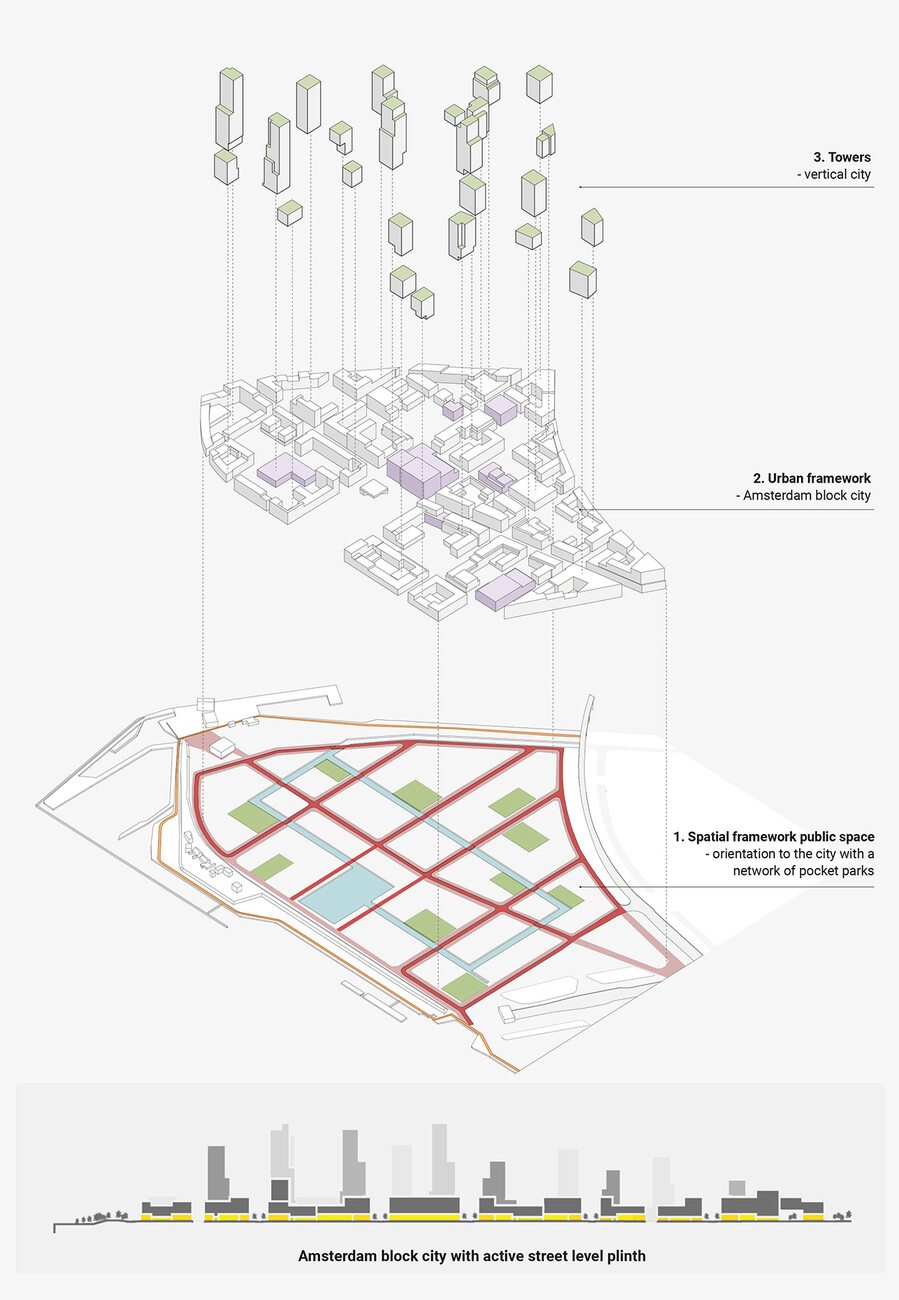

Plans to build on this artificial island have been in place for quite some time now. This island is ideally suited because the A10 ring road around Amsterdam already passes over it and it now boasts an interstate ramp of its own. Tram tracks were laid there back in 2005, opening up two more artificial islands to the east and extending up as far as the inland sea. A master plan by Amsterdam-based architectural practice Burton Hamfelt envisaging a kind of mini-Manhattan on the island was approved in 2016. Despite its picturesque name, the “Sluisbuurt”, literally “locks or sluices district”, has been designed as a high-rise quarter with 28 tower blocks ranging from 30 meters to 125 meters in height distributed all over the island right up to its tip and soaring up in an orchestrated choreography. To date, Amsterdam has only built this high in isolated cases; indeed, never before has there been a high-rise district that is so heavily developed anywhere in the city. This new scale promises not only the best panoramic views out over the historic old town and the water, but also, and more particularly, 5,500 new apartments (30 percent of them subsidized housing) and a good 100,000 m2 of office and retail space. Building on this kind of scale right on the waterfront is bound to be complicated. Despite this, the aspiration is for the district to meet the highest ecological standards. Alongside public transport, bicycles will also (as is to be expected from Amsterdam) play an important part in this.

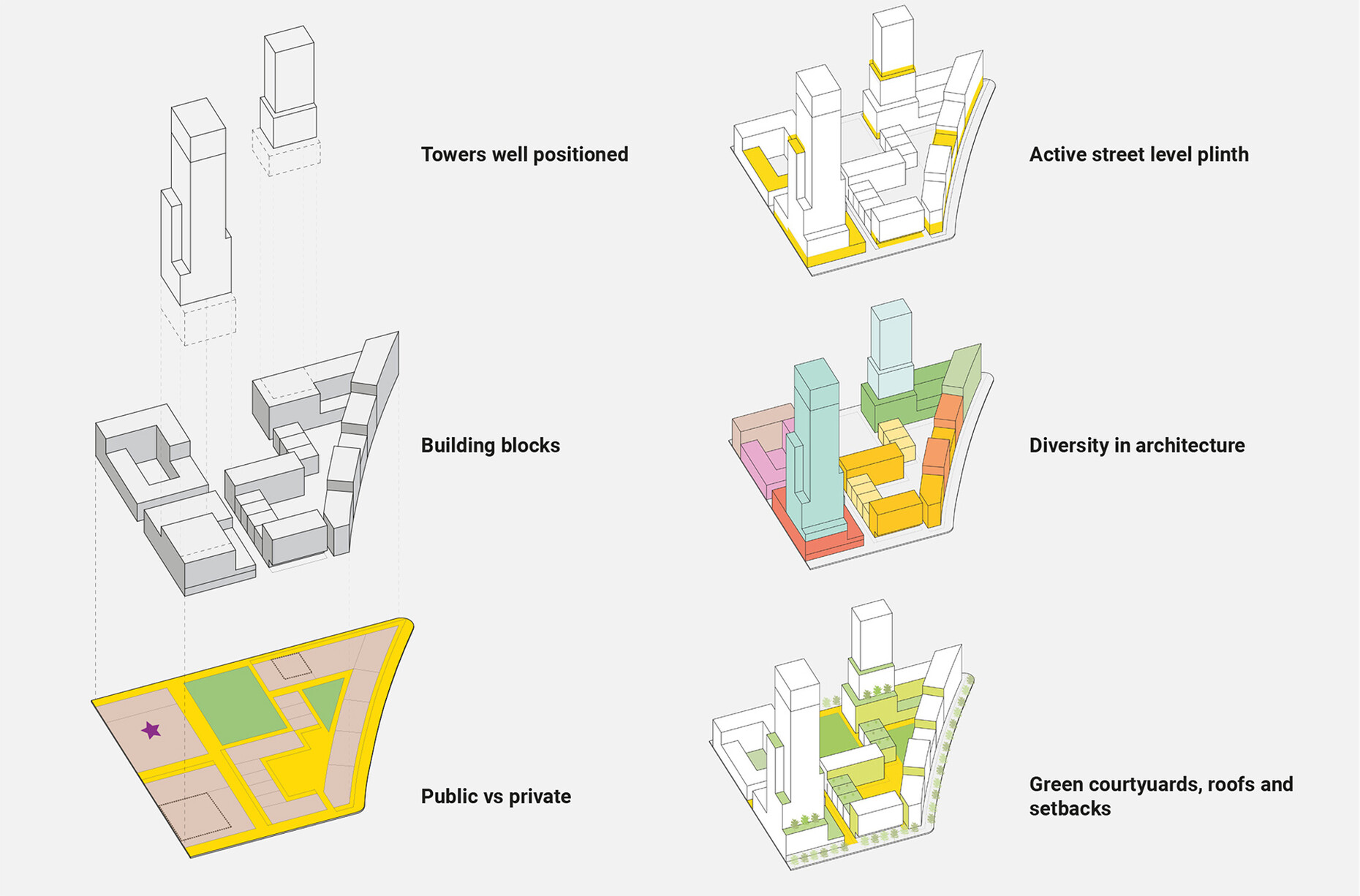

The initial firm plans for the first module in this new district have now been made public. The call for tenders was won by a private syndicate of bidders, notably the investor groups EarthY and Fakton Capital which had a highly promising urban building block designed by Barcode Architects (Rotterdam) and krft (Amsterdam). The project goes by the name of “Patchwork”.

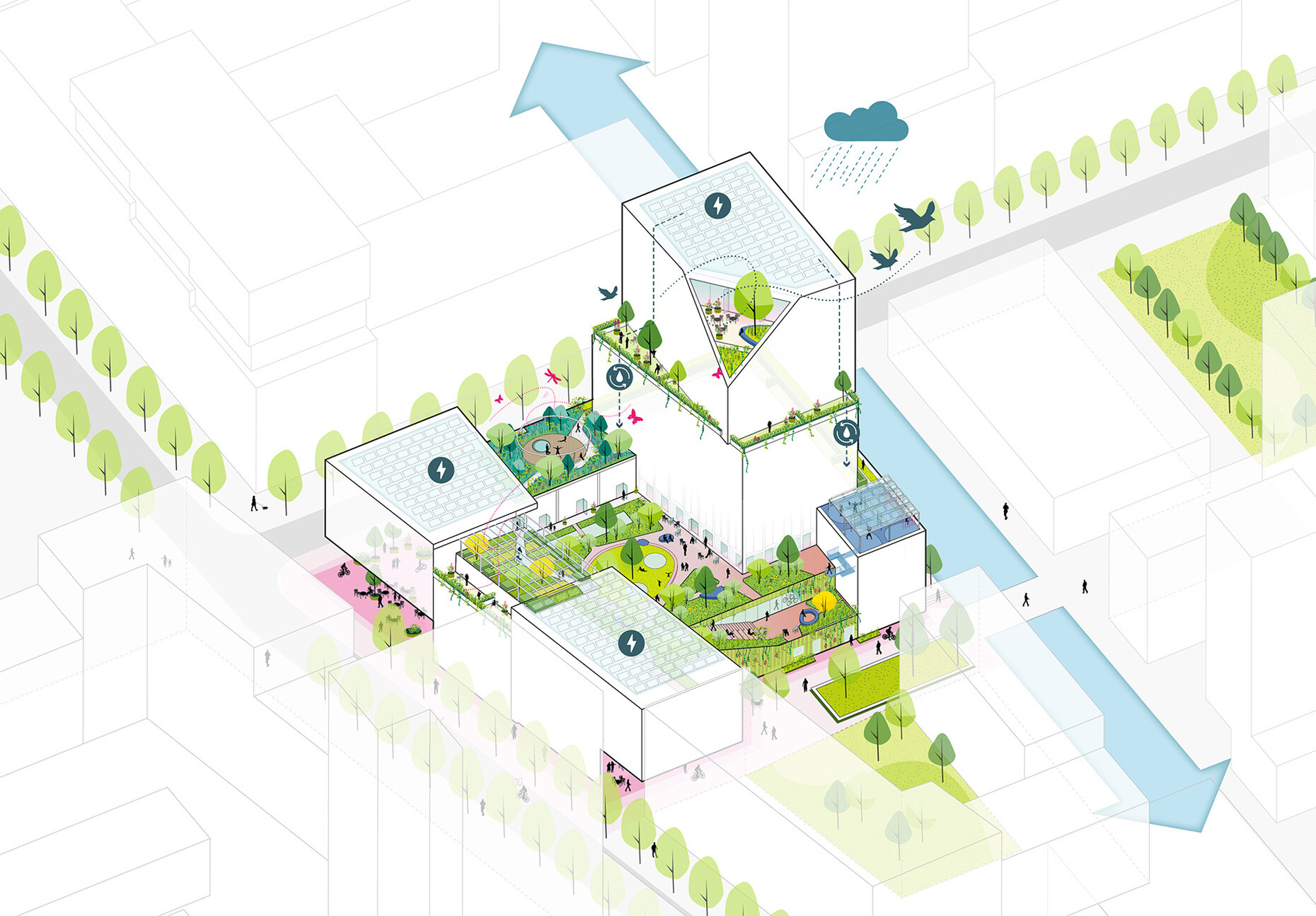

In “Patchwork” the aim is to produce a high-rise block with a good 19,000 m2 of usable floor space intended mainly for residential purposes, but, in the podium and along the surrounding streets, retail and office space as well. At the heart of the building there will be an atrium, a lively, semi-public center with a large parking garage for bicycles and a supermarket. There are also plans for smaller retail units, such as a bakery, a café or a bistro and a fitness center. A network of broad outside staircases will lead to a central roof garden in the atrium which will be accessible to the general public. There will also be five more roof gardens open only to the tenants and residents. Some of these are scheduled to be interconnected and their names reference the functions envisaged for them: the Yoga Garden, Picnic Garden, Sports Garden, and Meeting Garden. The objective of these gardens is to enhance residents’ quality of life, encourage social contact with the new neighborhood and to be effective against heat and heavy rainfall, as well as promoting biodiversity, despite the building’s volume, with such measures as nesting places and beehives.

Diversity is the buzzword for this architecture. Each of the two practices has divided up their block into eight sections; the two structures clearly distinct from each other and boast different dimensions, window grids and façade materials. To the northeast, the elements have been stacked on top of one another like building blocks to form a tower measuring 60 meter in height. Around here will be the location, at some point, of a major crossing in the new district, a place where users of the broad cycle thruway will be able to dash from east to west towards the city center. Of the eight components that will go to make up Patchwork, four will be clad with brickwork in differing shades of red. With this in mind, the plan is for Dutch startup StoneCycling to produce the relevant bricks from demolition waste and residual materials. Other sections of the façade will be clad with Kerloc tiles consisting mainly of natural pulp that is completely recyclable. Moreover, there will be solar panels on the roofs and façades. The supporting structure at the building’s core will consist of a base, plus three access cores made of low-carbon concrete. The rest of the frame will be executed entirely in timber, the beams and the ceiling in plywood board or solid wood. In other words, the entire building can be considered a timber construction. According to the architects, the large number of ecological measures associated with the building will result in savings of around 4,400 metric tons in CO2 emissions. With the large quantities of wood and the recycled materials in the façade, when Patchwork is complete it will store as much as 344,000 kilos of CO2.

It could therefore be said that if Patchwork does live up to its promise once it has been finished, it will indeed represent an excellent beginning for Amsterdam’s new, sustainable neighborhood – and a small but progressive 21st-century Manhattan into the bargain.