SUSTAINABILITY

A shared language

Anna Moldenhauer: Where do you get all the information that your team then processes?

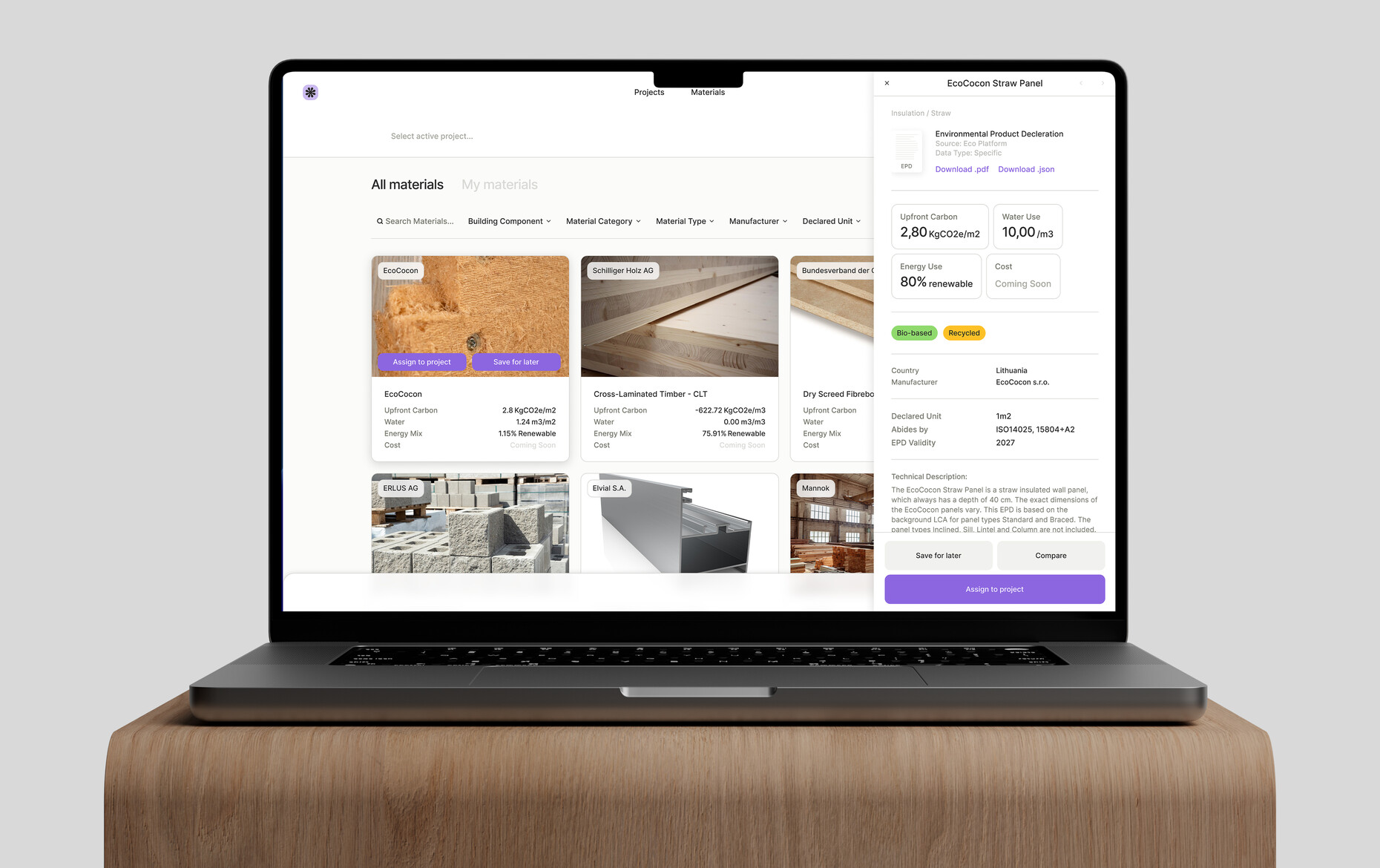

Kika Brockstedt: We primarily obtain the data from the EPDs (Environmental Product Declarations), meaning the standardized documents that contain the information on the environmental impact of a product based on a lifecycle analysis. These allow you to gauge, for example, how much water and energy went into manufacturing an item, where the energy in question came from, or how much carbon dioxide was required in the various phases. The problem is to how to make all that data readily accessible, as every environmental product declaration tends to run to several pages and the contents are not easy to understand at first glance. For this reason, our first objective was to collect all these data and extract the information from them that is of relevance for us to achieve our climate targets. So, what we did was digitize and normalize just about every EPD we could find in Europe. Added to which, by analyzing all the various different reports our hope is that we can come up with holistic data that focuses not only on the carbon consumption, but also factors in other decisive criteria such as water consumption or the use of renewable energies.

To what extent can AI tools assist when undertaking the analysis?

Kika Brockstedt: It certainly can, for example, when it comes to extracting information from the PDFs and classifying the various products. The lion’s share of the information is only available as pdf files and cannot immediately by read by a machine. With the help of AI processes, the data can be extracted automatically in a high quality in order to integrate them into digital processes. There can be mistakes in the documents that people have compiled, and the AI can then scrutinize the data for abnormalities, for example a comparatively above-average positive entry for a specific category of material. This enables comparability, classification, and subsequently verification. Moreover, the AI learns from enquiries from our users and inputs the insights gained into our “Recommendations Engine”: By means of the latter, the AI then ascertains which materials people frequently search for and what alternatives could be considered. It takes a while until alternative data have also been inputted into the system, but AI offers great potential in this regard.

In other words, the AI supports you in wading through the mass of information and evaluating it. You just mentioned using AI to help with the verification of data. How exactly does that work?

Kika Brockstedt: When analyzing a class of material such as cement you can assess on the back of the large volume of data available whether the figures stated in a particular EPD, for example, are within the range to be expected compared with all the others, and whether they thus survive a plausibility check. The machine-learning system identifies whether a calculation arrives at results that fall outside the scope of what it has learned and thus draws anomalies to our attention. Rule-based expert systems monitor for inconsistencies in the data. Our system then blocks such data, and they get subjected to manual scrutiny.

How do you define which environmental indicators such as water consumption levels or the potential for inclusion the circular economy are assessed and which are not?

Kika Brockstedt: We have sustainability experts on our team, and they analyze in advance which criteria from the overviews should be subjected to evaluation. After all, the EPDs aren’t always filled in completely, and sometimes there are no figures given for items such as “circularity index” or “reusability”, to name two examples. Other times, we can guestimate fairly accurately some of the figures on the basis of the data already disclosed. That said, knowing what information is lacking is also helpful as you can use it to rate what needs to be changed going forwards.

The Revalu service is spread across different levels: There’s the free-of-charge front-end platform, the Material Cloud and an Innovation Hub behind a paywall. Could you perhaps explain in detail what the respective options are?

Kika Brockstedt: Sure, the platform per se is available to all users free-of-charge, because that was one of our aims, namely, to make all the information available with a view to greater sustainability, with a special focus in the process on the activities of small architecture practices. In other words, everyone can search for materials and by applying different impact criteria compare them, for example as regards the percentage degree to which their manufacture has involved renewable energy sources. We want to create a space where bio-based and recycled materials are presented in a readily comprehensible manner. Furthermore, there are many innovative materials for which there are not yet any EPDs. We also take them on board, rate them in terms of their properties, and they can therefore also be found and categorized using the platform. In addition, when using the platform, you can store materials and assign them to a particular project in order, for instance, to run minor calculations for a wall you want to build. That is a great help specifically in the early days of a project, as it gives you a rough idea of things. The earlier you do the calculations and can put your finger squarely on the carbon footprint, the better positioned you are to reduce it.

The next level is the service we offer to implement the data in the individual software programs and internal digital tools that an architecture practice is actually using, as a result of which the data ca be directly incorporated into the architects’ workflow. This is what we are mainly focusing on at the moment, as the architecture practices require massive amounts of verified data for their calculations and we can make precisely such volumes available. It is also interesting to see what data we receive enquiries for and what goals the respective companies have in the process. This enables us to learn how much change in the direction of real sustainability is really being called for.

In your opinion, are there “good” and “bad” materials?

Kika Brockstedt: I personally am of the opinion that you can’t actually assess things that way. How sustainable a material is itself depends very strongly on where the project is being constructed. My take on this is that a broad diversity of solutions and materials is what counts here. If, in the future, we only build high-rises out of wood then we have not understood something. The emphasis cannot simply be on replacing a given material used by one that is purportedly better. In order to act sustainably we have to rethink our consumer patterns and our very systems. Cement is in and of itself a great material that can certainly be advanced further. Wood on its own is not the solution because we of course need our forests. In order to come up with real innovations, we need to develop both new materials and advance existing ones. At the same time, we need a general rethink with a view to decarbonizing supply chains, preserving existing buildings, and fostering mutual support within the sector. If you always focus only on one number, for example the carbon footprint per square meter, then you scan easily overlook the fact that a different solution might be better for the project in question. Let me give you an example: Calculating clay buildings is very difficult, but they are highly sustainable because the soil itself is used as the material. If sustainability is to be holistic, then social influences is also one of the points we need to consider. In that regard, transparency of the data is a first step along the way as it creates a shared language.

When developing Revalu did you encounter challenges that none of you had expected?

Kika Brockstedt: Good question. To be frank, an awful lot of them. Quite apart from the environmental criteria, it must be technically possible to erect a building. And achieving a combination of the two is not easy at all. We will need a whole lot more pilot projects that can be used to prove that taking a different approach is not just conceivable but actually possible. We can’t simply change the big picture overnight in a single step but need to take the small steps in-between to reach that goal. In the form of Revalu we have managed in convincing companies to utilize alternative materials and that in itself is an initial success. It’s really important that things can be scaled up in order to allay the concerns of all those involved that using an alternative product will possibly lead to delays in workflow. In order to explore new paths, someone has to take the first step in the new direction. And that’s exactly what we’ve done.

So, what are the next steps?

Kika Brockstedt: They revolve around further data integration. On the basis of our Material Cloud we want to press the pedal on digitizing in applied cases. We’re collaborating not just with architects and developers, but also with cities and local authorities in order to find out how we can, on the back of computations then arrive at forecasts as this would enable us to reach the climate goals faster. Parallel to this, we’re working on expanding the data sets in order to be able to tap into more environmental criteria. The intention is to offer services that are so diverse that users can use Revalu to produce customized calculations as to what is key for their projects.