|

Propaganda and change

Architekturikonen auf den BY Elser Oliver

Apr 24, 2015 No, let’s not talk about how the Federal Republic of Germany is taking to the floor at the Expo 2015 in Milan with a pavilion architecture that is once again completely trivial. In fact, you really have to dig deep in the past to find a striking German contribution to one of the World Expos. This is all the more annoying as architecture is one of the obvious key currencies of any Expo and Germany is home to any number of buildings that have without doubt written architectural history. Just remember the dates and the names of the architects and the images pop up before your mind’s eye: 1929 Mies van der Rohe; 1937 Albert Speer; 1958 Sepp Ruf and Egon Eiermann; 1967 Frei Otto and Rolf Gutbrod. And after that? Even at the Expo 2000 in Hanover, the first Expo to be held on German soil, the host country only attracted attention for having missed the opportunity: Not for the first time a pavilion design chosen in an architectural competition was suddenly dumped and replaced by a middle-to-average structure. But enough of complaining. Why we have now gone 48 years without an outstanding pavilion is a question to which perhaps the Federal German Ministry of Economic Affairs, which is responsible, has the answer. Fading fame Internationally, architecture is a bit weak at the moment: Who can remember a pavilion for Expo 2010 in Shanghai that started out in the race with similar ambitions, as had the Olympic Games two years earlier, which brought forth a whole series of architectural icons (the Bird’s Nest Stadium, Swim Stadium, CCTV High-Rise)? Well, as regards Shanghai at least the hairy British Pavilion created by Thomas Heatherwick and the huge Chinese pagoda come to mind. Renowned architects such as Bjarke Ingels (BIG) or Buchner Bründler designed the edifices for Denmark and Switzerland respectively, and pinpointed the dilemma in which all Expo architecture has found itself for some time now: If a pavilion is popular, then it has to cope with such masses of visitors that the focus is more on the infrastructure necessarily required to handle the task. Ramps led up to Copenhagen’s “Little Mermaid”, ski lifts scooped the astonished Chinese up and into a kind of gigantic model of Switzerland. The main preoccupation of an Expo visitor it to queue, meaning that avoiding long waiting times has become a key element of the architectural brief. |

First Expo in 1851 in London: The Crystal Palace designed by Joseph Paxton. Photo © Philip Henry Delamotte, Wikipedia.org

|

|

A great beginning: Crystal Palace The very first of the world expositions revolved around a great building, in terms of size and stature. There were not yet national pavilions, and when in 1851 the first such Expo opened in London in the midst of Hyde Park it took place in a “Crystal Palace” erected in line with plans by Joseph Paxton. The edifice was so breath-takingly modern that to this day it is revered as the paragon for a form of architecture reduced to its bare bones. Contemporaries already debated whether the building was a huge step toward a new architecture of the Industrial Revolution, applauded it, and at times were critical of it, one example being Gottfried Semper. In London it was not just an outer skin for exhibits that had arisen, but the very symbol of a new age. On show were products from just short of 30 countries. Austria, for example, chose as its champion mechanically made furniture by Thonet. The participating nations presented their wares in their own sections, to which end the bright interior was in part subdivided by dark curtains. While official architecture in the mid-19th century was still stuck firmly in historical shapes, the Crystal Palace and the industrial buildings popping up everywhere constituted the first prototypes of Modernism. |

Expo 1889 in Paris: The Eiffel Tower by Gustave Eiffel and Stephen Sauvestre.

Photo © commons.wikimedia.org |

The Eiffel Tower was 324 meters high and – at his time – the biggest building of the world. Photo © commons.wikimedia.org

|

Expo 1889 in Paris: The Galerie des Machines designed by Charles Louis Ferdinand Dutert. Photo © commons.wikimedia.org

|

|

Big, bigger, Expo: the Eiffel Tower and Galerie des Machines The architecture in 1998, the 100th anniversary of the French Revolution, was even more daring. The Eiffel Tower stood 325 meters tall, making it the highest building in the world, and “Galerie des Machines”, with a footprint of 422 by 114 meters and a maximum height of almost 50 meters was by far the largest covered structure made by human hand. Since the Paris World Expo of 1867, next to the exhibition halls proper a kind of theme park had arisen. There, the participating nations were represented not by their latest products but by their respective traditional architecture. Imitations went so far that in 1873 at the Vienna World Expo part of Venice’s canals and gondolas were reconstructed. In the heyday of Colonialism, “Negro villages” complete with genuine inhabitants were also highly popular. |

Expo 1929 in Barcelona: The German Pavillon designed by Mies van der Rohe. Photo © Berliner Bildbericht, Stiftung Bauhaus Dessau

|

The Pavilion of Mies van der Rohe was the first building with an open ground plot. Photo © CC by SA, commons.wikimedia.org

|

|

Change and Self-Contemplation: The grand era of the Pavilions of Nations commenced in 1929 in Barcelona. At quite a late date, if you think about it. As the beginning of the century had already witnessed the first dedicated building exhibitions. In 1901 and 1908, pioneering buildings had been erected on Darmstadt’s Mathildenhöhe, including the world-famous Wedding Tower, a pure symbol, as had been the Eiffel Tower. In 1925, Paris hosted the “Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes”, a “miniature World Expo”, with buildings by Le Corbusier and Konstantin Melnikov that were to become key milestones of modern architecture. Only two years later Stuttgart celebrated the opening of the Weissenhof Estate with another large exhibition. Before the inhabitants moved in, the houses were open for viewing. In such a climate of spectacular stagings of the ‘New’, in 1929 the German Pavilion for the Barcelona World Expo arose. Architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe created an almost purpose-free house that served only as a place to be visited by the King of Spain during the opening ceremony. Otherwise it represented nothing other than itself – and therefore the stunning principles of a new form of architecture and a new sense of space. In a study that was to become one of the classics of architectural sociology, Juan Pablo Bonta succeeded in showing that the pavilion initially was as good as ignored and only later emerged as an icon of Modernist architecture. |

Expo 1937 in Paris: The German Pavilion designed by Albert Speer.

Photo © Bundesarchiv, CC by SA, commons.wikimedia.org |

Expo 1937: The Soviet Pavilion designed by Boris Iofan.

Photo © Bundesarchiv, CC by SA, commons.wikimedia.org |

|

Demonstration of power and rivalry: Albert Speer’s pavilion This was driven not least by the course German history then took: Modernism’s model country presented itself in a quite different manner in 1937 at the Paris World Expo, which was to become a portent warning of the massive conflict that was soon thereafter to push Europe into the abyss of disaster. Instead of Mies’s sense of instability and openness, Albert Speer’s pavilion of the “Third Reich” as a gesture of power carved in stone rivaling the Soviet Pavilion opposite. Given the way such architectural muscles were being flexed it could have seemed obvious to assume things would not end well. But in the shadow of the super-powers posturing, architectural change was also in evidence in Paris. Jaromír Krejcar designed the Czechoslovak Pavilion – a bright high-tech steel-and-glass affair, Josep Lluís Sert masterminded the Spanish Pavilion. On show there were among other things Pablo Picasso’s response to the German Luftwaffe’s bombing of the civil population of Guernica. Alvar Aalto’s Finnish Pavilion is one of the rare cases in which not only the outer appearance has lodged in people’s minds: The organically shaped wooden walls pre-empt the special Nordic version of a Modernism with a human face. |

Expo 1937: The Czechoslovakia Pavilion designed by Armoír Krejcar.

Photo © urbipedia.org |

Detail of the façade of Krejcar’s Pavilion. Photo © urbipedia.org

|

Expo 1937: The Finnish Pavilion designed by Alvar Aalto.

Photo © morehouse gallery.com, pinterest |

Expo 1937: The Finnish Pavilion designed by Alvar Aalto.

Photo © morehouse gallery.com, pinterest |

Expo 1939 in New York: The Futurama Pavilion designed by Norman Bel Geddes for General Motors. Photo © National Building Museums; Courtsesy Albert Kahn Family of companies, blogs.voannews.com

|

|

New York visions of tomorrow: Futurama by General Motors In 1939, the World Expo moved to New York, focusing not on the nations but on industry. The real crowd-puller was General Motors’ “Futurama”. On a kind of conveyor belt, visitors were whisked past a huge city Diorama that presented them with an astonishingly accurate forecast of America in 1960: Skyscrapers and highways paved the way for Auto City. Shell also contracted Norman Bel Geddes, who had designed the “Futurama”, to create a gigantic city model for the company. |

Geddes was stage and product designer. For General Motors he designed a Pavilion as a city of the future. Photo © with kind permission of General Motors

|

Futurama should have been a prototype of a futuristic New York in 1960.

Photo © with kind permission of General Motors |

Striking was the automated traffic system, which Geddes designed for his Futurama. Photo © with kind permission of General Motors

|

View at the inside of Futurama.

Photo © Norman Bell Geddes Street, Wikipedia |

Expo 1958 in Brussels: The Philips Pavilion designed by Le Corbusier. Photo © commons.wikimedia.org

|

|

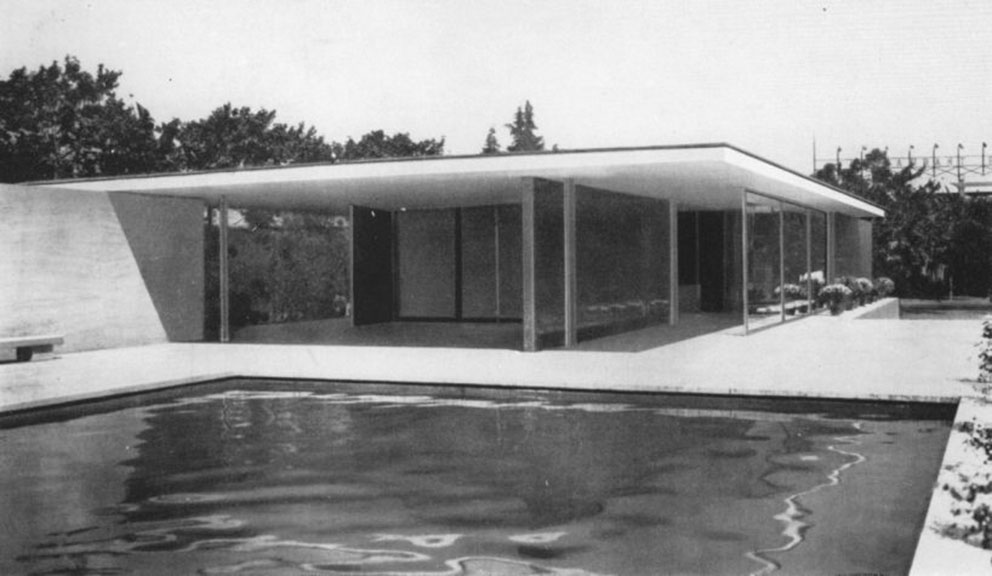

Media spectacle: Le Corbusier’s Philipps Pavilion At the 1958 Brussels World Expo it was a different branch of industry that invested big money in grand gestures. Now, it was no longer the auto or oil industry that was the avant-garde, but electronics corporation Philipps. The latter commissioned the world’s most famous architect Le Corbusier, together with composer and architect Iannis Xenakis to build a pavilion that would house an audiovisual installation. This building should bekame a world-famous landmark. Germany opted for a pavilion world devised by Sep Ruf and Egon Eiermann as a counter-symbol to the Speer architecture in Paris in 1937. The light Modernism was not the only option for the West. Neo-Classicist Edward Durell Stone clad the US Pavilion with an ornamental curtain, prompting Sigfried Giedion to sense the betrayal of Modernism. “Playboy architecture” was the accusation of the High Priest of avant-garde architecture. |

Expo 1958: The Atomium designed by engineer André Waterkeyn and the architects André and Jean Polak. Photo © flickr.comkmeron

|

Expo 1958: The German Pavilion designed by Sep Ruf and Egon Eiermann.

Photo © flickr.comkmeron |

Picture postcard view at the expo in Montreal in 1967 with the Fuller Dome in the background: It was influenced by new technologies resulting of aerospace and nuclear power.

Photo © Wikipedia.org |

|

Lego bricks and tens: Moshe Safdie, Frei Otto and Rolf Gutbrod Expo 1967 in Montreal remains to this day lodged in people’s minds thanks to the residential complex made of prefabricated concrete cells in the city designed by then then 29-year-old Moshe Safdie using a mass of Lego bricks. The Americans presented a Buckminster Fuller geodetic dome, the acrylic bubble of which burned down quite spectacularly in 1976 during renovation work, only to be rebuilt. Frei Otto joined forces with Rolf Gutbrod to create a kind of dummy run for the Munich Olympic stadium in 1972. The German Pavilion’s tent-like structure was torn but in Vaihingen outside Stuttgart to this day the trial structure stands, essentially a life-size model used to prove the feasibility of the tent idea before work went ahead in Montreal. |

Expo 1962 in Seattle: Space Needle designed by Edward E. Carlson and John Graham.

Photo © Cropbot, Wikipedia |

Expo 1964 in New York: The New York State Pavilion Tent of Tomorrow designed by Philip Johnson. Photo © Cropbot, Wikipedia

|

Expo 1967 in Montreal: The Habitat 67 designed by Moshe Safdie. Photo © Wikipedia

|

Expo 1967: Playground and fun fair spirit: The area at the Expo.

Photo © archimaps.tumbl.com |

Expo 1967: The Pavilion Pulp and Paper Industry sponsored by the Canadian Pulp & Paper Association (CPPA). Photo © archimaps.tumbl.com

|

|

Robots and lamp bulbs: Kenzo Tange’s Expo Plaza The Expo in Osaka in 1970 was the highpoint of post-War technological fervor, a last celebration of the future before the oil and ecological crises became the prevailing issues of the 1970s. Kenzo Tange and Arata Isozaki erected a giant steel mega-structure, the “Expo Plaza”. A total of 64 million visitors flocked to the show (not topped until Shanghai with 73 million) to see the huge robots and brashly colorful pavilions for themselves. Germany presented a composition by Karlheinz Stockhausen in a dome created by architect Fritz Bornemann. The Swiss also eschewed self-adoration in the form of presentations of goods made in Switzerland and instead opted for a pavilion by Willi Walter that simply amounted to a huge, sparkling and resonant tree made of thousands of light bulbs and aluminum rods. |

Expo 1970 in Osaka: The Swiss Pavilion Radiant Structure designed by Willy Walter. Photo © Wikipedia

|

Expo 1970: Inside of the Festival Plaza designed by Kenzō Tange.

Photo © Domusweb.it, Pinterest |

Expo 1970: Tange was the planner of an area with 3.3 square kilometers. Photo © Domusweb.it, Pinterest

|

Expo 1970: The Fuji Pavilion with an air filled membrane construction.

Photo © Wikipedia |

The Festival Plaza, a colorful city of Lego: The Expo’s motto was “Progress and harmony for humankind. Photo © Wikipedia

|

|

Firmly under the sign of sustainability: the World Expos from 1992 onwards The idea of the Expo as one giant architectural spectacle got lost during the course of the next decades. Expos such as that in New Orleans in 1984 had to contend with financing difficulties. Sevilla 1992 and Lisbon 1998 both used the Expo more or less skillfully as a form of event-driven urban development project. Expo 2000 in Hanover promised sustainability: A large part of the exhibition took place on the existing trade-fair complex and a few country pavilions were then meant to be dedicated to new uses. But one of the icons, the Dutch Pavilion created by MVRDV with its staggered landscapes, now stands on the grounds, completely dilapidated, serving only as a popular photo theme for fans of neo-Romantic ruins. Less ecologically damaging was Shigeru Ban’s Japanese Pavilion, made of pressed rolls of recycled paper – they had to be reinforced with wood and then sealed with a fire-protective coating, however. Peter Zumthor’s Swiss Pavilion differed from many of the others, where you had to wait in long queues to get in, as it was quite literally perforated with entrances and therefore pleasantly easy to visit. It was made of stacked wooden boards and reached a height of nine meters on a footprint of 50 by 50 meters. And the German Pavilion in Hanover … well, let us keep our silence. “German values” were represented not that far away in Wolfsburg by the Volkswagen corporation’s “Auto City”: A project that is just as ideological and spiced up with architecture as the 1939 “Futurama”. |

Expo 1998 in Lisbon: The Portuguese Pavilion designed by Alvaro Siza. Photo © Magnus Manske via file upload bot, 2011

|

Expo 1992 in Sevilla: View at the roof construction of Tadao Ando's Japanese Pavilion. Photo © Pilar, Flickr

|

Expo 1992 in Sevilla – Tadao Ando. Foto © Pilar, Flickr

|

Expo 2010 in Shanghai: The UK Pavillon designed by Thomas Heatherwick. Photo © Green Archer

|

|

Oh sober, vain contemporary Expo Milan set out to do a lot of things differently. But the team at Herzog & de Meuron was not able to get its way, as Jacques Herzog recently revealed in an interview with Florian Heilmeyer for Uncube magazine. The images currently doing the rounds suggest it’s going to all be Vanity Fair again. Where Herzog & de Meuron had proposed quite the opposite. Of course, Expo 1970 was also a colorful cornucopia of buildings cashing in on all manner of capers. The difference being that back then the world gazed in innocent astonishment. And we’re long past that point and for years have been witnessing Expos as zombie-like zest forced upon us by those who feel we should set our eyes on messages that are as rapid as they are vapid. |

Expo 2000: The Netherland’s Pavilion designed by MVRDV. Photo © Matthias Hensel

|