Planning More Flexibly

Anna Moldenhauer: Professor Klumpner, you're researching the definition of informal urbanism and its effects on the city. Is architecture for cities too form-driven and too little purpose- and socially-oriented?

Prof. Hubert Klumpner: You make an interesting distinction between architecture and the urban, which I agree with. In my opinion, the city is only one form of urbanisation. That's why I'm also interested in the process of the informal. With our work, both in teaching at the ETH Zurich and within the framework of urbanthinktank_next, we try to shed light on variants that often receive little consideration. We get very involved with implementation. There's been a focus on the topic of cities for about ten years now, but it's been communicated in a way that's hard to understand. You've probably heard the standard statement that more than 50 per cent of people live in cities. This is wrong! People don't live in cities, but rather in an urbanised context. If you move away from the abstraction of these statements and get closer to reality, you very quickly come up against a contradiction. Urbanisation is a process and I'm interested in the architecture that emerges from it.

You've built a bridge between science and practice for the Urbanthinktank. Your goal is to create socially and ecologically sustainable projects for which operative urban tools have been put together. Do you think education needs to be more practice-oriented than it is now?

Prof. Hubert Klumpner: We constantly ask ourselves that question at the university. Universities are intrinsically specialised and not interdisciplinary, and faculties usually don't work together. I find that to be a problem.

So should we question the norm that has been put forward so far?

Prof. Hubert Klumpner: Let me give you one example: In 2010, our projects was part of the exhibition Small Scale, Big Change at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), which was curated by Andres Lepik. He actually managed to convey the idea that the “Social Turn” was a movement that generated a proverbial turnaround in architecture. In the context of the city, many people are exposed to great risks – the model is costly and socially unfair. Nevertheless, we hold to the view that there is no other solution. As an urban planner, however, I would dispute that. I think there are many other possibilities. Urbanisation will continue to be our major project, but it's not only reflected in the city; we usually talk about things too abstractly. One argument in favour of cities is that they are the only places where innovation takes place. Switzerland, for example, is urbanised but not urbanised – only about 26 per cent of the population live in cities. Still, no one would argue that Switzerland is a backward place. We have to deal a little more with the diversity of reality. urbanthinktank_next is our design studio, and that's where I've been working on this issue with my team for many years. We're very much concerned with the implementation of ideas. We've recently been commissioned by the UN to publish a volume on Sustainable Development Goal 11, (Sustainable Cities and Communities), which is very much focused on design. We believe that sustainability in design is actually a question of imagination that we can solve more successfully if we can sort out more clearly what is actually happening. We should redesign our methods. We also need to constantly reinvent our tools so that they play a role in this process.

The Urbanthinktank was founded in Venezuela. What approaches in urban design would you like to transfer from your work there to our global understanding of architecture?

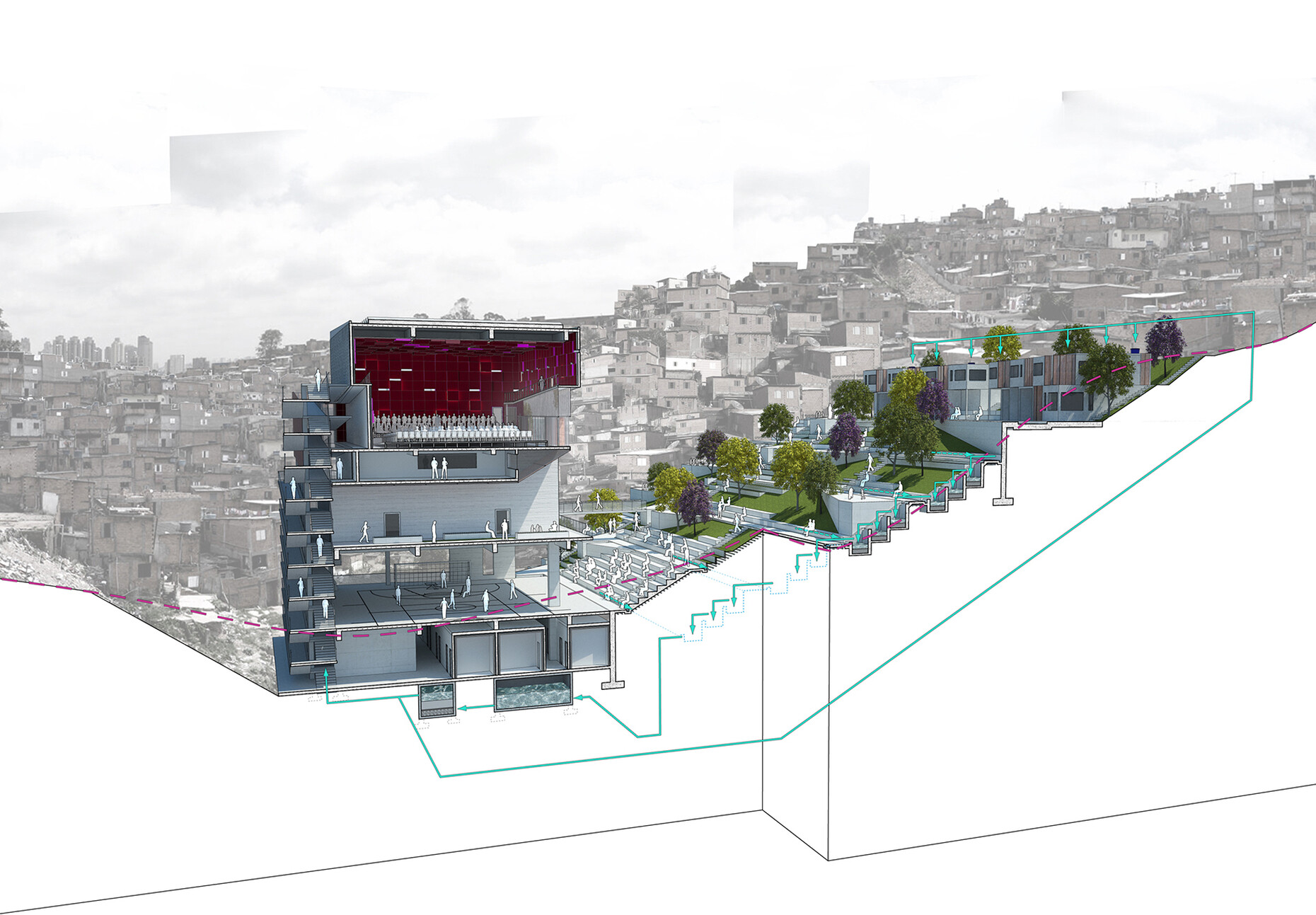

Prof. Hubert Klumpner: I think that those of us in Western Europe, North America and Asia can no longer ignore what's happening outside our traditional horizon. Our models, our methods and tools don't work. For example, our first built project in Venezuela was a public toilet in one of Caracas' hillside slums in La Vega. We called the approach "Learning from La Vega". We used the project to show that hydrologic cycles, and in general everything that is circular, can be tied to a small object that we then scale up. In our western culture there are very few design offices working on a sustainable sanitation system, for example, EOOS's research for the save! toilet, even though we know that the current solution is not globally sustainable. Research like this takes place on the margins, but nonetheless addresses fundamental questions. Developments in informal settlements in the globe's newly growing regions are also of great importance for the global North. In the future, our urbanisation processes will be determined much more by what happens in other areas of the world – as well as by migration. We call this the formalisation of the informal and the informalisation of the formal. The informal actually stands for structures that we have not yet registered. That means we have to discover them, describe them and include them in our vocabulary and repertoire. City centres are undergoing a lot of change and that's a design opportunity for us. The post-war assumption that we'll conquer the world with modernism is no longer true. Nowadays Modernism looks pretty old. It has been occupied by informal markets, incorporated and creolised. For me, in order to truly face the challenges of the real world, implementation is necessary, and testing in realistic conditions. Otherwise, research remains theoretical and is too detached. This is sometimes evident in projects like the Torre David office tower, where we test whether a building really needs air conditioning or lifts. Our task is thus to develop prototypes for new functions.

In other words, our thinking is not holistic enough, is not practically oriented enough. Is this also perhaps because those of us in the West are used to seemingly infinite resources and haven't had to adapt our way of life so far?

Prof. Hubert Klumpner: It's very important to me to convey the idea that the cities and the forms of urbanisation we're looking into are not characterised by asceticism. If you have a lot, then solidarity seems to lie in reduction. That's a big misunderstanding and also the fear that leads to hardly anyone getting into this research. In 2021 we organised an exhibition about architecture and urban development at the Museum of Applied Arts (MAK) in Vienna as part of the Vienna Biennale for Change under the direction of Christoph Thun-Hohenstein. Within this context we researched what the topic of climate change actually means. In Europe, people talk about climate change with a certain sense of guilt, but asceticism is not the means of choice here, rather circularity. Our goal is to create cities based on pedestrians, cities that consume as little energy as possible and produce hardly any waste. This model already exists in the favelas of the world, where there is extreme density, little energy consumption and everything is within walking distance. The generation of waste is very low because everything is reused. This is an aspect that's only just being discovered in architecture. The reasons why no one wants to live in such areas are the social factors of security and protection. This is where we could work on ways to improve this urban model. We not only work in South and Latin America, but in South Africa and the Balkans as well. In South Africa there’s a famous book on urban planning during apartheid that's similar to the German Neufert Bauentwurfslehre, which is about building norms and spatial requirements. I would argue that most cities built today are constructed on the basis of standards books like this. That means that specific economic and social structures are built, but they are not urban in principle. If we were to really build cities where many people could live, we would have to plan for more urban space. In Europe we have the impression that this exists everywhere, even if it's basically just simulated. Even a train station concourse isn’t public, because it’s also a controlled space. In our experimental projects we’ve therefore taken plazas and squares out of the private sphere and successfully made them available to the public again. I’m afraid I don't think the current Smart City Movement, i.e. the movement towards a technology-based city, is effective either. Technology is a good tool, but it can’t be the principle. Instead we need to go back to the principles of public space, and that means cities also have to be places of conflict. The concept of the smart city makes us believe we can live in safety – but that won’t work. Conflicts in cities cannot be regulated or merely hidden away.

I’s like to talk to you briefly about the discussion concerning the future design of city centres. There are people who say we have been building the wrong type of city centre for decades. What would the ideal approach be for you at the moment?

Prof. Hubert Klumpner: My idea is quite contemporary, i.e. that there is no such thing as "wrong" in that sense. We often lack imagination when it comes to what we can do with a given situation. Here, too, my experience is that the cities of the global South already have many solutions for the rest of us. In Sao Paulo, for example, the lack of space is so great that an urban motorway is sometimes temporarily opened to pedestrian and bicycle traffic. Formally, it remains a motorway, but the new use turns it into a kind of High Line. There are also quite a few small plots of land under the motorway that are rented by boxing clubs. When the motorway is closed to vehicles, these clubs then use the area for training. We simply have to be much more flexible about what we can do, and that's where even existing infrastructure that we now think of as being a mistake will no longer bother us. The plazas, tunnels and structures we've built in the past can easily be transformed. Our task is to see what needs to be changed so that we can figure out how to use such structures more flexibly. We'll never be able to solve climate issues if we don’t solve social issues as well. In architecture and urban planning, trends are changing too quickly at the moment. I think it would be better if we anticipated more, and didn't throw everything overboard too hastily. And this means we need to know why these things are there in the first place. I notice this in my own work as well: We were less concerned about the materials we used in the past. We were much more concerned about social opportunities. Still, I would say you can't give up one and simply replace it with the other. This also applies to the current discussion about city centres, where we should ask whether a change in use wouldn’t make more sense than tearing everything down. I don't think we'll bring about ecological change if we limit ourselves to green facades and photovoltaic panels. Sustainable change requires a complete about-face in many areas.

While we’re on the subject of trends, I'd like to address the subject of mobility. The benefits of using cable cars for more than just tourist attractions are being increasingly discussed in our latitudes. Would you say that this form of mobility could be integrated into our current mobility structure?

Prof. Hubert Klumpner: It's probably not a surprise to you that we won’t solve the problem of traffic in cities by simply changing our sources of energy. It might improve air quality, but it won't solve the big challenge of how we use our existing land. If we want to change our cities, we need technologies that don’t rely on forms of transport. We explored this approach a good ten years ago as part of the Audi Urban Future Initiative together with Stylepark. You have to think much more about how you connect individual mobility modes and how you move as a person in a city. Analysing that makes it possible to see where offering a cable car would make sense. In Zurich, where I am right now, there's the Dolderbahn, which is more than 100 years old and is used every day by many people as a means of transport. Fundamentally, however, we have to say goodbye to the assumption that any form of mobility can be integrated into any system. For successful mobility concepts, the respective climate, topography, human behaviour and ecology needs to be understood. This also means we have to take the decision-making power away from groups whose lobbies map out everything in advance and instead engage in an open-ended discourse. This basically describes the method design approach, where different stakeholders are involved in order to determine what really makes sense.

Urban sustainability was an issue for you very early on – like when you founded the Sustainable Living Urban Model Laboratory. Do you think there are approaches that receive too little attention in the current discourse?

Prof. Hubert Klumpner: What I would like to emphasise is solidarity, the importance of social aspects. Many of the proposals we've discussed won't work if we only make them available to the few people who can actually afford them. In many places around the world the reality is that they don't offer any of these promised urban qualities, neither in the middle of the city nor on the periphery. We need to have a holistic view in other parts of the world concerning the topic of digitalisation, sustainability and social balance. We need to think about everything more systematically, because these challenges can only be solved in a network. We are currently at a turning point, and I see a great commitment among young people to help shape change in cities. A sustainable debate can only happen if projects aren't limited to one particular place.

What are you working on at the moment?

Prof. Hubert Klumpner: Among other things, we're working on a master plan for the city of Sarajevo. The previous one dates back to the 1980s, but the world is not moving along the lines that were thought out decades ago. In this particular case, there was also the massive destruction caused by a war. Sarajevo was once a city of great innovations; they had the first electric tram based on a timetable. They built blocks of buildings there that served as models for similar blocks in Berlin and Vienna. For urban planning purposes, we've created a laboratory situation on site as well as a digital twin of the city, which gives us an opportunity to test different scenarios. To do this, we've developed a studio vehicle to measure air pollution, because Sarajevo is currently one of the ten most polluted cities in the world. It takes more courage to work with an open mind and make adjustments where necessary instead of putting guard rails up in advance. We have the chance to do this today ─ and there's a willingness to create and use a more flexible process, in my opinion. Now we just need to get started.