Horst’s second photo book was released shortly after the end of World War II: This time plants, shells and minerals took center stage. Photo © Conde Nast / Horst Estate, from: ”Horst: Patterns from Nature” by Martin Barnes, Merrell Publishers

Horst decided to juxtapose the jagged, corrugated natural elements marked by the lines of life to a highly objective index with all the technical details: type of film, developer liquid, paper, camera, and filters. Photo © Conde Nast / Horst Estate, from: ”Horst: Patterns from Nature” by Martin Barnes, Merrell Publishers

The photos were taken in Mexico, New York Botanical Gardens, and along the Atlantic and Pacific coasts. Photo © Conde Nast / Horst Estate, from: ”Horst: Patterns from Nature” by Martin Barnes, Merrell Publishers

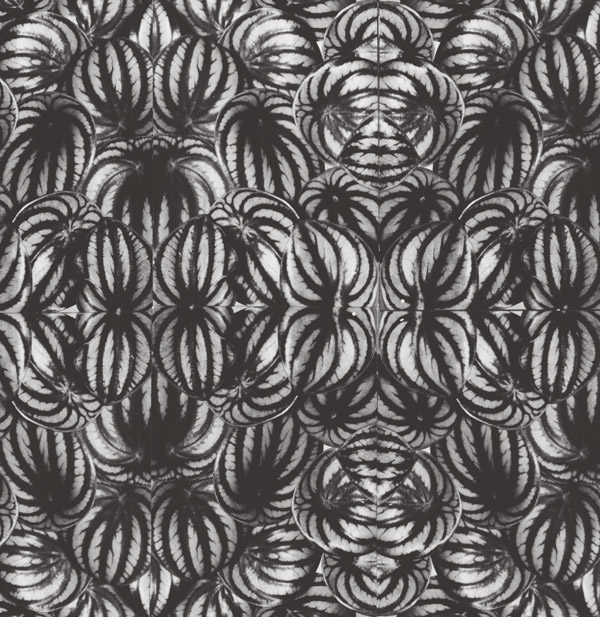

Horst made four contact prints from one of his 2¼ x2¼ or 5x4 negatives - two the 'correct' way round, and two 'flipped' across the vertical axis to produce a mirror image. Photo © Conde Nast / Horst Estate, from: ”Horst: Patterns from Nature” by Martin Barnes, Merrell Publishers

Horst P. Horst directing a fashion shooting in 1949. Foto © Roy Stevens, Time Life Pictures, Getty Images

"The pictures found here are of common objects daily passing before our eyes. Nothing has been added to enhance them," Horst P. Horst writes. Photo © Conde Nast / Horst Estate, from: ”Horst: Patterns from Nature” by Martin Barnes, Merrell Publishers

|

Patterns for creative regeneration

by Annette Tietenberg

Dec 10, 2014 In the 1930s and 1940s Horst P. Horst brought a shot of coolness, elegance and glamour to the world of fashion photography. In the style of Hollywood’s “Black Series” he staged women like antique goddesses for “Vogue” magazine, transforming the likes of Elsa Schiaparelli, Marlene Dietrich, Bette Davies and Coco Chanel into icons of a new type of woman. His preference: A stark contrast between black and white paired with the antagonism between light and shadow. He carefully constructed this by means of studio lighting, over-the-top stylization and dramatic sublimation of the statuary, and all these elements swiftly became his trademark. The man who fathered high glamour was born in 1906 in Weissenfels an der Saale under the name of Horst Bohrmann. A student in Walter Gropius’ furniture carpentry class at the Bauhaus, at the age of 23 he made for Paris hoping to work as a draughtsman apprentice under Le Corbusier. There he became acquainted with Latvian Baron George Hoyningen-Huene, who introduced him to the in-circle of actors, musicians, artists, and writers. It was Hoyningen-Huene who put Horst in contact with “Vogue” magazine, where he gained a reputation first as a model and then as a photographer. Horst spent the years between 1935 and 1939 commuting between the “Vogue” editorial rooms in New York and Paris. Shortly before the outbreak of World War II he managed to transfer completely to New York; however, with the United States’ entry into the war in 1941 he was classified as an “enemy alien”. The lawyers at “Vogue” obtained an exemption for Horst and thanks to the permit he was able to work as a photographer, albeit with restraints. Still suspected of being a collaborator, he was permitted to use a camera, if only on the Vogue studios property. And when he was finally granted US citizenship he adopted his professional name as a photographer: Horst P. Horst. In 1943 he was drafted into the US Army. Luckily he did not have to go to the front and was able to continue working in his profession: He was dispatched to the Pentagon where he took photographs of generals. Horst’s second photo book was released shortly after the end of World War II, a compilation entitled “Patterns from Nature” featuring 100 contact prints. This new publication was not commissioned by “Vogue”; it was an artistic project for which Horst himself was responsible. The book was based on a very stringent concept: The handy six-by-six-centimeter format coincided with the size of the Rolleiflex negatives. The images were printed on transparent paper, meaning the pages could be held up against the light like slides. The choice of theme was radically different from what Horst had done before: This time plants, shells and minerals took center stage. Horst decided to juxtapose the evocative power and symbolic meaning of these jagged, corrugated natural elements marked by the lines of life to a highly objective index. For each and every photograph in the set he provided all the technical details: type of film, developer liquid, paper, camera, and filters. Yet the disclosure of the production technicalities did nothing to dent the magic power of the images – on the contrary. Against the backdrop of their technical reproducibility these images unfolded a potential that had hitherto been nature’s prerogative: the ability of creative regeneration. The 1946 publication has been out of print for decades now. The project gradually sank into oblivion and hardly made an appearance in the various major retrospectives held in Horst’s honor since the 1980s. Which makes the rediscovery of a series of 37 experimental photographs relating to the book’s visual subject matter all the more spectacular. They present a perfect symmetry that Horst distilled from nature. To this end, he developed a special montage technique. A single image was composed of up to 16 contact prints, which, similar to a Rorschach inkblot test, are aligned on a central axis and have been variously arranged side by side, atop one another, and as mirror images. The result: a pattern that seems to extend infinitely thanks to the all-over principle. As if seen through a kaleidoscope, the repetition of the same unvarying image offers a view both of the essential architecture of nature and the construction principle underlying the images. Fortunately, the photographs that have survived in Horst’s archive (he died in 1999) have now been reprinted as an anthology in their entirety. And in two editions at that: firstly, in the form of the prints currently on show at London’s V & A and, secondly, in a book whose format this time takes its cue from the print size (30.5 by 25.5 centimeters) Horst once used for several images exhibited in 1977. Thanks to Horst’s notes we can decipher the origins of the photographs that form the basis for the montages: He took them in 1946 in New Mexico, in New York’s Botanical Garden, in the woods of New England, and along the Atlantic and Pacific seaboards in the US. Botanist Jamie Caffery accompanied him on his expeditions to the plant kingdom. Precisely why Horst should have opted for flora and fauna at this very point in time is a topic of much speculation in the book. There is some evidence in favor of the hypothesis put forward by Martin Barnes, who claims that at a time when the atrocities came to light which the Germans had committed during World War II in the concentration and death camps, Horst sought to salvage the little that remained from the paradise that had been the Weimar Republic and which he himself was fortunate to have witnessed. He acknowledged his German roots by embracing the tradition of New Objectivity and taking inspiration from the visual idiom developed by Karl Blossfeldt, Albert Renger-Patsch, Alfred Ehrhardt, Hans Finsler, et al. At the same time he forged links with major photographers of the country he had chosen as his adopted home, including Edward Weston and Paul Strand. And, last but not least, if we believe speculations made by his partner Valentine Lawford, it may indeed have been Goethe’s primordial plant that Horst endeavored to render by using photographic means. In the famous words of Émile Zola, we might then say that during this phase Horst P. Horst regarded art as “a piece of nature seen through a kaleidoscope”.

Horst: Patterns from Nature |