Photo © Archivio Superstudio

The Italian architect Gabriele Mastrigli supposedly is one of the most renowned adepts of the work of Superstudio, one of the most radical and visionary architecture collectives of the 1960s and 1970s. On the occasion of the 50th anniversary of Superstudios founding in Florence in 1966, he has curated a large show at the Maxxi Museum in Rome, appropriately titled “Superstudio 50”. With this exhibition, he has also published one of the most comprehensive (and heaviest) volumes on the group’s oeuvre, the 790-pages-read “Superstudio. Opere 1966-1978”. Ludwig Engel and Barbara-Brigitte Mak spoke to him about why Mastrigli sees the work of Superstudio as realistic and definitely “anti-utopian”.

Ludwig Engel: You have spent years researching the work and legacy of Superstudio. And your efforts have now culminated in the “Superstudio 50” exhibition at the Maxxi in Rome, which you’ve curated together with three members of the group. You’ve also edited the ultimate catalogue of their works–an 800-page comprehensive book that comments and lists all and everything Superstudio produced in the 12 years of its existence. What is the most exciting, most thrilling aspect of Superstudio you came across?

Gabriele Mastrigli: By investigating architecture, its significance and its role in contemporary society, Superstudio offered a way of looking at architecture not as a problem-solving discipline, but as a powerful device to understand the world in which we live. At the same time, they discovered that this world is nothing but a reflection of our intentions, aspirations, desires and nightmares. The world, particularly the Western world, is a mirror of man. What Superstudio proposes in the end is an attitude to architecture that is intrinsically related to art and philosophy. “The mind was dreaming. The world was its dream,” said Jorge Luis Borges. And this is not utopia. This is sheer reality. This is what I've discovered. The many years of work on the book Superstudio Opere 1966-1978, published on the occasion of the exhibition, was fundamental to understanding the value of this message.

Photo © Gabriele Mastrigli

Barbara-Brigitte Mak: Your perception of Superstudio's practice as “anti-utopian” is really interesting. Why are these thoughts not prominently discussed in the exhibition?

Gabriele Mastrigli: Superstudio’s “anti-utopianism” was not a topic that could be readily presented in the exhibition, because it is mostly intrinsically embedded in their narrative work. Truly anti-utopian are projects like the Twelve Ideal Cities or the work “Salvage of Italy's Historical Centers”. But you can only understand these undertakings if you read the texts. The stories–that in fact are exhibited–reveal the dystopian side of the proposals. The problem is that people in exhibitions usually look at the images, especially in the case of Superstudio's images!

This anti-utopian impetus is very much underlined in the selection of the texts for the book, for instance the text “Utopia, Antiutopia, Topia”, and also in my introduction, where I explain the relationship of Superstudio to politics and how they differ from Archizoom.

Barbara-Brigitte Mak: What difference did you find?

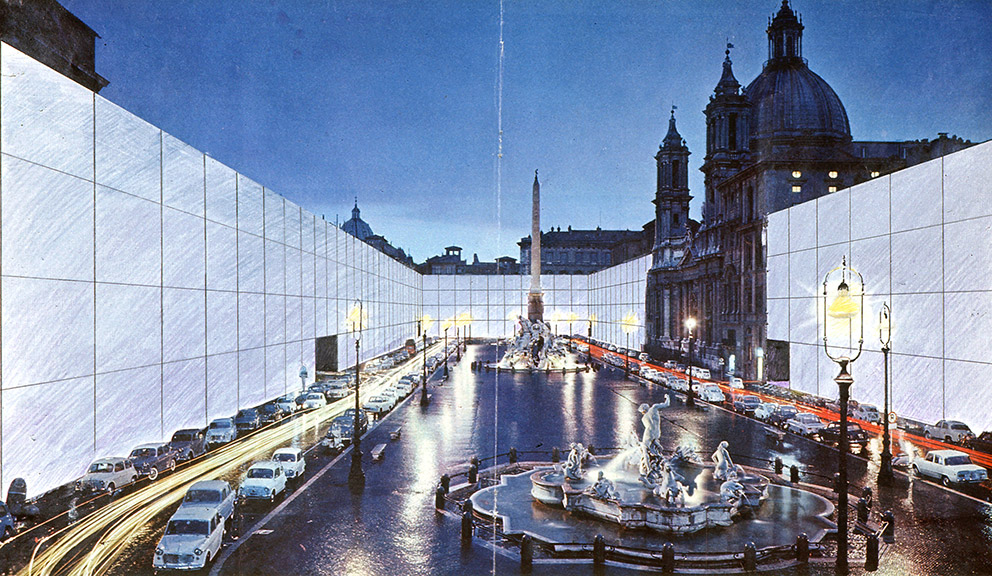

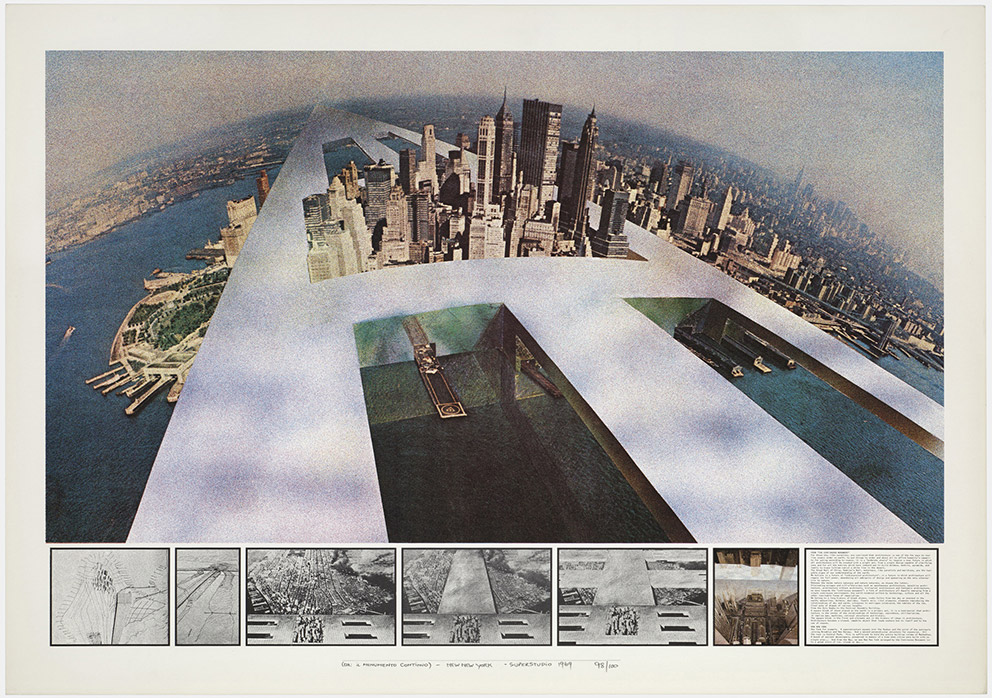

Gabriele Mastrigli: Where Archizoom elaborated a conceptual model that exploits the paradoxes of capitalist society, Superstudio emphasized the rhetoric of progress–the belief in the future–as the fuel driving the capitalist engine. Therefore the Continuous Monument is a dystopian image of a future in which everything “new” is reduced to the generic image of an abstract and conceptual past: In the end, the gridded solids of the Continuous Monument are no different from the Egyptian pyramids, Roman aqueducts or the Great Wall of China. So Superstudio’s critique is directed against this faith in the future that characterizes other architecture avant-garde groups like Archigram. Today we often see all these groups placed under the same umbrella, but that is a mistake. The contemporary fascination with all these 1960s and 1970s architectural utopias is nostalgia for an “easy” world. A world of infinite possibilities, of imagination au pouvoir. In reality these were times of deep social and cultural conflicts. Not by chance Superstudio’s deeply anti-utopian approach set out to eliminate shortcuts, “mirages and will-o'-the whisps”,

as they say.

Ludwig Engel: But doesn't this “realist turn” at the beginning of the 1970s with “Peak Oil”, the publication of “Limits to Growth” and the emergence of environmentalism also hold true for most of these collectives? Haus-Rucker-Co’s shelters for a polluted environment or Ettore Sottsass' embrace of Arte Povera come to mind. What makes Superstudio so special in this context?

Gabriele Mastrigli: For sure Superstudio shared this kind of “realist turn” with other groups, but in my opinion they were the most balanced between design and concept. Sottsass was an artist and a real designer. He didn't have any real big scale and conceptual approach–with a few exceptions like Il pianeta come festival. Haus-Rucker-Co on the other hand was a group that heavily leaned toward the conceptual, maybe too much, as typical of the Austrian avant-garde groups. Superstudio didn't escape from architecture, from investigating what they saw as the limits and the possibilities of architecture. They didn't turn into conceptual artists, or mainly furniture designers. They simply tried to be architects, super-architects.

Ludwig Engel: Would Superstudio’s mode of working as a political collective still be possible today? And if so, do you see any new collectives that work in the same spirit?

Gabriele Mastrigli: After the 1960s, the group as a message-vector, but also as brand, has become a standard in architectural experimental practices. Nowadays almost all groups sell a brand that goes beyond their technical knowhow. I see Superstudio’s influence in many different forms, but it wouldn't be fair to individuate specific genealogies of descendants of Superstudio. As they said at the time, once you put a label on a movement, you kill it. However, the branding heralded the end of what was then called “architettura radicale” in Italy.

Barbara-Brigitte Mak: Is any form of radical architecture dead today? Or has maybe the “research architect”, who works on understanding the present in an anthropologist's manner, posing questions instead of giving answers, rather incorporated that spirit? In this context the practice of the French architects Lacaton & Vassal as a disputable member of this tribe comes to my mind.

Gabriele Mastrigli: I agree, radical architecture is not dead. On the contrary there's plenty of radical architecture all over the world. In a different scale, it is exactly like modern architecture. We live in a system that has definitively metabolized the figure of the architect-cum-artist, or the researcher-cum-architect, think of Rem Koolhaas’ Venice Biennale two years ago. Representation is the field in which this aspect is most evident. Today more and more architects sell images, avant-garde images. So I think that for sure there is a space for something radical today, but it is something that has to stress the discourse and not to simply find solutions. If you want examples, I think that part of the work of Dogma, for example their manifesto Stop-City, goes into this direction.

Ludwig Engel: Building on the great works Superstudio produced, how can we assess their legacy today? How could their approach be made feasible for a contemporary, future-oriented practice between architecture and art?

Gabriele Mastrigli: Since the beginning Superstudio fueled many architecture practices that wanted to rediscover a genuine approach to architecture without any direct social implication–or better without a much deeper political implication–from the younger Florentine groups like Ufo and 9999 to Rem Koolhaas’ and Elia Zenghelis’ Office for Metropolitan Architecture. This is an approach still valid in principle. But Superstudio did not look at architecture as a problem of style. Once avant-garde is reduced to whatever cliché, avant-garde is dead. Not to mention when avant-garde is a critique of avant-garde!

Exhibition

Superstudio 50

MAXXI - Museo nazionale delle arti del XXI secolo

Via Guido Reni 4/A, 00196 Rom

Sun September 4th, 2016

www.fondazionemaxxi.it

Catalog

Superstudio.

Opere 1966-1978

ed. by Gabriele Mastrigli

790 p., Italian

Quodlibet, Macerata/Italy, 2016

ISBN 978-8874628131

68 Euro

Photo © Fondazione Maxxi