All in the service of space

Halifax is situated picturesquely on the east coast of the Nova Scotia peninsula, where the Bedford Basin and the harbor are linked to the Atlantic Ocean by “The Narrows”. Established on Mi’kmaq First Nations territory in 1749 by British Colonel Edward Cornwallis, together with some 2,500 settlers, as an army outpost and named after the then President of the Board of Trade the Earl of Halifax (1716 – 1771), nowadays the city is part of the Halifax Regional Municipality and is currently the business and cultural center of Canada’s Atlantic seaboard.

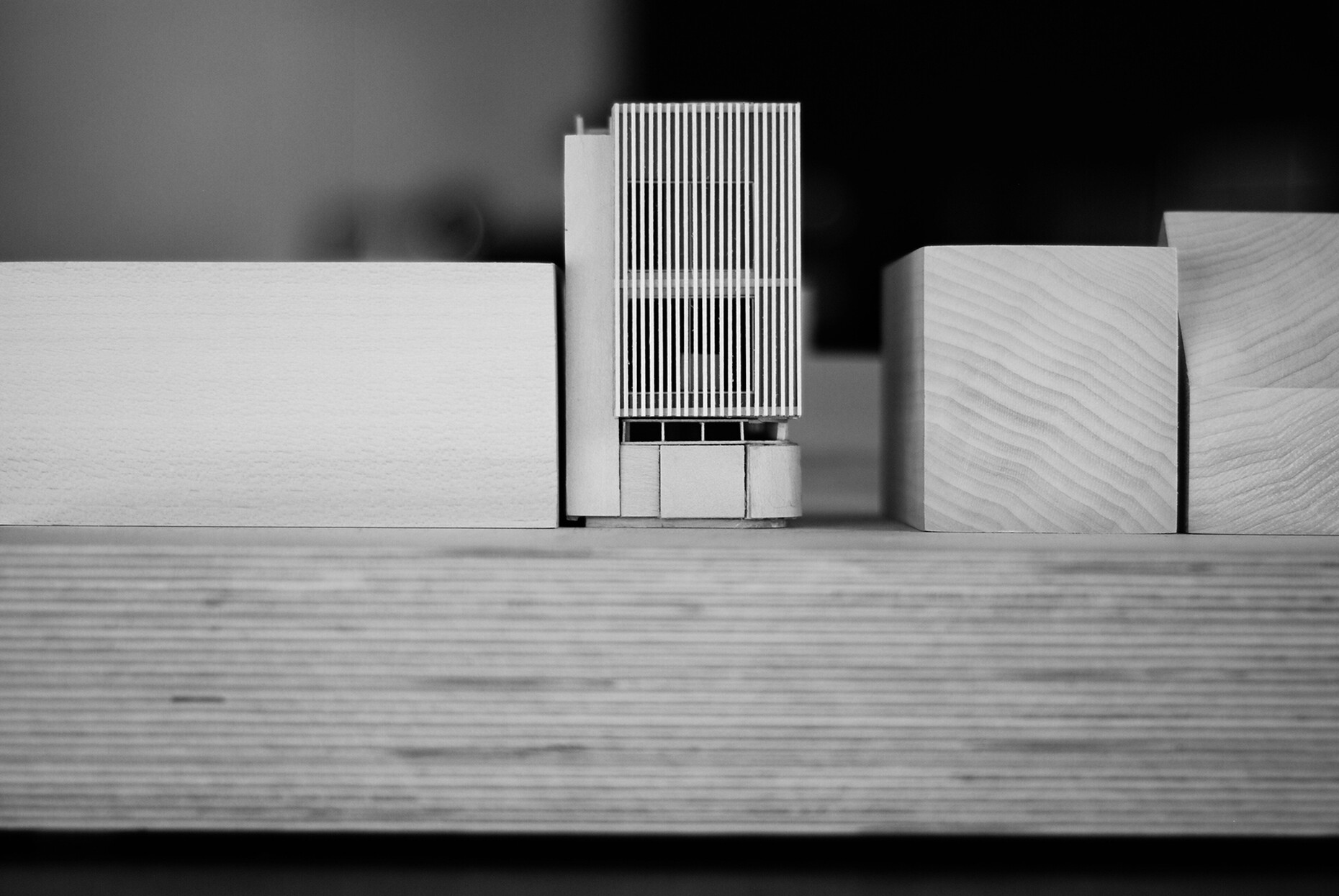

The North End is considered to be Halifax’s chic heart: Favored by creatives on account of its many cafés, restaurants, and nightclubs, it is a popular destination for an evening out. Canadian architect Omar Gandhi has designed a home for himself on a hitherto unused plot some 1.5 km north of Halifax Citadel (dating from 1856) and only two blocks away from the harbor. When he planned the building, he was intending also to locate a second branch of his architectural practice here, and thus to add to the main office in Toronto. The streets in this part of town are lined with the kind of single, two and three-story buildings that, at first glance, have nothing in common with European notions of urbanity and only reveal their urban density if one considers the purpose and function of the urban space, with its numerous public and semi-public facilities relating to cultural and communal life. As is so often the case, in Halifax, too, the combination of once unpopular dockland district and the kind of creative potential that is skilled at filling the empty spaces has formed a veritable seedbed for gentrification, with many long-standing locals thus being forced to vacate the area.

The majority of buildings boast wooden cladding, but brick also crops up from time to time, typically there is a small flight of steps leading up to the front door. By contrast, Omar Gandhi has opted to reinterpret the existing podium as a unit hermetically sealed from the street. The bright beige masonry that now curves along the side of the plot whereby a strip of smaller windows at lintel height emulates the line of the pavement. Inside the plot, the main entrance a small courtyard that at the back abuts the garage leads down seven stairs to the podium story. The floor, stairs, half-height walls, and the garage, like the podium story, are all made in the same brickwork. The two upper stories rest on this tectonic base and cheekily protrude on two sides out over the curved wall. The wooden cladding used here also references a local feature, whereby Omar Gandhi has rotated the wood from the horizontal to the vertical, and thus ensured the frontage’s notable formal independence.

Approximately two years after completion, the cladding, which is made of Thuja occidentalis, a cypress tree, has grayed well and thus pleasantly blends with the buff tones of the masonry podium. While the podium story was originally meant to house his own studio it is now let out to an organization specialized in community projects in the North End, such as homes for the homeless. Given the well-filled order book, Gandhi’s practice had outgrown the available space during the construction period. The street front points to the house’s inner organization: Along the southeast edge of the plot to the neighbor on that side there’s a supply and circulation block likewise made of masonry that links the three floors by a stairwell. In the toilets and corridors located here, the bricks used in the podium floor crop up here and there on the inside and outside. The first upper floor resembles an inserted room shell: clad right round in oak, the space expands into the depths of the plot.

A wooden table illuminated by one of two "PH5" luminaires by Danish designer Poul Henningsen forms the center of the dark, forward section of the living room, flanked by a Gaggenau Series "400 kitchen", the worktop island of which forms the spatial and formal counterpart to the kitchen table. The floor-to-ceiling windows facing the street are in part shaded by the vertical wooden louvers in front of them, while in the rear section a narrow window strip about one meter high at floor level offers a view of the small courtyard. However, the room opens above all upwards, and quite spectacularly at that. The majority of daylight comes flooding from above down the two-story lightwell such that it seems obvious to position the group of seating arranged around a “Modern Lounge” sofa by Montauk here.

The second upper floor is home to the three-person family’s private rooms: two bedrooms and the obligatory walk-in closet as well as two bathrooms. Four additional stairs again differentiate the degree of privacy from the street in the rear section of the house. The dark-green Ceragres tiles from the company’s “Dotcom” series contrast gracefully in the bathrooms to the warm wooden tones and the beige-grey brickwork, and with their slightly sandy texture are also reminiscent of limestone or gravel pebbles, and meld beautifully with the faucet fittings: Dornbracht’s “Tara Wide Spread” was chosen for the wall-mounted mixer. The impact of the material is enhanced still further by the fact that once again light only comes from above. As if coming full circle in spatial terms, the room facing away from the street boasts a kind of inner window onto the airspace of the lightwell above the living room. The house is topped by a roof terrace along with a small roof garden that relate the spatial sequence of the house back to the urban space outside.