In small parts

It is quite something for two of the world’s undisputedly most innovative architecture studios to present two residential construction projects in parallel. Yet when these two highly comparable projects in terms of building costs and size additionally aim to create apartments for the middle class, one can certainly hope to see trailblazing concepts with a wider application for the housing problems that is arising in almost all major European cities.

First, the facts: The Stockholm real-estate developer Oscar Properties has realized two residential complexes in the Swedish capital with Rotterdam-based OMA, led by Reinier de Graaf, and with Bjarke Ingels’ studio BIG from Copenhagen. Both buildings are located some 30 minutes on foot from the very center of Stockholm, one to the west, the other to the east. The BIG project encompasses 169 residential units, that of OMA 182. All apartments target the same group of buyers: affluent middle-class singles, couples and families, and not wealthy foreign investors. That said, given current real-estate prices in Stockholm, which are on a par with cities like Munich and Frankfurt, this still means that the 105-square-meter show apartment in the “Norra Tornen” designed by OMA will set you back around 1.3 million euros. Consequently, the floor plans in both buildings are conceived such that even apartments measuring some 80 square meters in size are intended to accommodate a family of four – no doubt a realistic prospect of the future of housing construction in German cities, too. Ingels and de Graaf both emphasize that the efficient use of space was a central aspect informing their designs.

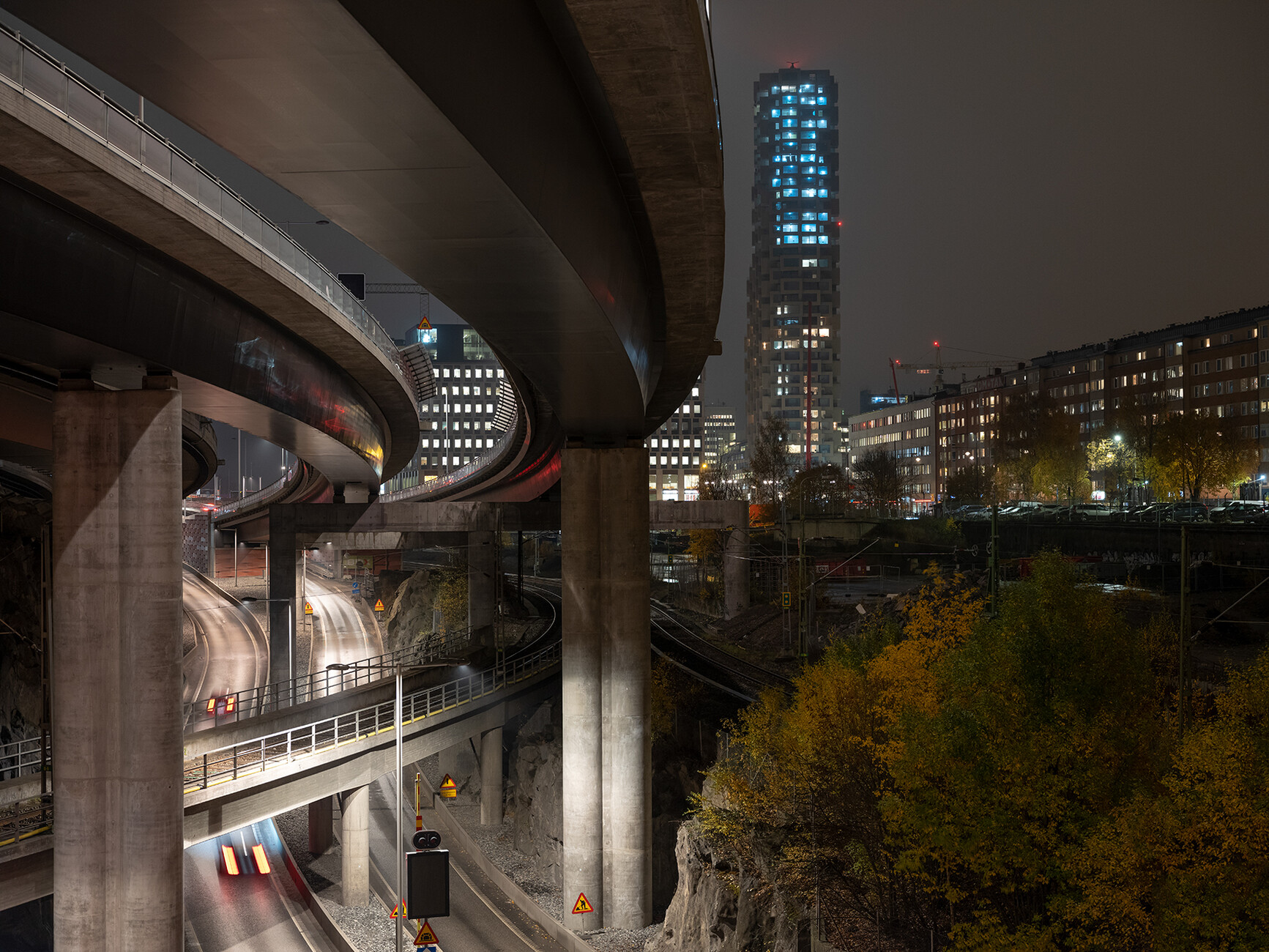

Now on to the differences. Viewing the buildings from the outside, there is no danger of confusing the two. OMA’s “Norra Tornen” is, namely, a 125-meter-high tower on a small leftover plot in the middle of an already densely built-up part of the city, whereas “79 & Park” by BIG is a stepped structure rising from two to 12 stories with a courtyard and rooftop terraces on the edge of a nature park.

Formally speaking, “Norra Tornen” is unmistakably influenced by Brutalism and the modern concepts of the 1960s and 1970s, as Reinier de Graaf freely admits. Anyone who has read de Graaf’s excellent book “Four Walls and a Roof” will know that he is a great supporter of experimental construction, as practiced in the UK by the Smithsons and the architects of London County Council (LCC), for example, or in the Netherlands by such architects as Herman Hertzberger. Yet de Graaf also cites another, surprising reason for referencing Brutalist forms, namely, he aims with his polarizing design, which is not (yet) aligned with mainstream tastes, not least to scare off speculators. He wants the buyers of the apartments to actually live in them. It seems architect and investor agreed on this point.

The result is a large structure composed of pixel-like cubes that echoes both Moshe Safdie’s “Habitat 67” in Montreal and Kurakawa’s “Nekagin Capsule Tower” in Tokyo. Like his role models, de Graaf also seeks to achieve the greatest possible variation (another of the architect’s favorite topics) using prefabricated standard elements. Thus the concrete cubes alternately protrude and recede in a slightly offset layered arrangement. There is another advantage to breaking down the large structure into individual modules, which has to do with the genesis of the building. Originally, an office high-rise was envisaged on the site. When this project was nixed, the City suddenly declared that the volume of the finished architectural design was binding. OMA and Oscar Properties were not allowed to exceed this volume anywhere in the plans. Structuring the building with individual cubes enabled them to use the available airspace to best effect.

A vertical rib pattern lends the concrete façade structure and depth. The ribs themselves feature a coating of brown washed concrete and colored pebbles, which emphasizes the reference to Brutalism. A great many series of tests were necessary to achieve the color and structure the architects were looking for. Yet the decision to bathe the tower in a brownish hue was down to an accident: When a laser cutter was trimming the first 3D model of the high-rise, it charred the outer surfaces a dark color. This inspired de Graaf and his team to “embrown” the real architecture, too.

The apartments in “Norra Tornen” range from the studio apartment measuring 44 square meters to the 281-square-meter penthouse; most of the units are sized between 80 and 120 square meters and have two or three bedrooms. What is noticeable is the almost complete absence of hallways in the layouts. Most bedrooms lead off from a central living, dining and kitchen area. In addition, only some of the apartments have porches and even family dwellings do not necessarily have a second toilet. The bedrooms are in part very small, but have large windows and sometimes small balconies, preventing any sense of claustrophobia arising. Here, overall OMA proposes highly pragmatic solutions for family living even on small footprints, attesting to an excellent eye for feasibility – far beyond experimental approaches.

The second project “79 & Park” is instantly recognizable as a BIG design. Here the Copenhagen-based architecture studio has put a new spin on a concept it has successfully used in the past: an apartment block arranged around an inner courtyard and with strongly varying heights on the different courtyard sides. The most extreme form of this concept realized to date is BIG’s multi-award-winning “Courtscraper,” namely “Via 57 West” in Manhattan. At one corner of the rectangular courtyard the New York building towers up 142 meters, while it barely reaches three stories on the opposite side.

In Stockholm BIG has applied this concept in highly moderated form – comparable, for instance, with “8 House” in Copenhagen completed in 2009. The building is aligned with the park situated to its south and west, to which the courtyard opens up on its lower developed sides, while the taller sections of the building shield the courtyard from the city. Moreover, the flat structures afford many residents of the other wings a park view. Like OMA, BIG also structured its building using pixel-like individual modules, which here have a square footprint and are grouped around the rectangular courtyard. Yet the modules facing the courtyard are rotated by 45 degrees, giving the building a zig-zag shape. Thanks to this rotation, the architects can have far more windows facing the park. At the same time they put the shape of the façade to creative effect: One side of each “prong” of the zig-zag is almost entirely glazed, the other consists of the building’s cedar wood cladding. Thus depending on where you are standing, the façade looks either to be made almost entirely of glass or else like a sculptural wooden form.

The apartments in “79 & Park” range in size from 35 to 137 square meters and from studio to five-bedroom apartment. Unlike in “Norra Tornen,” here there are numerous duplex apartments. Moreover, the ceiling height varies. On the one hand this makes for in part highly aesthetic solutions, where the large principal space is pleasantly structured into living, dining and cooking zones. Yet in some places one cannot help but think that perhaps the planners didn’t quite master this additional design challenge – such as when narrow hallways suddenly have a ceiling height of over five meters. The architects make use of the building’s steel skeleton as a further design element: Struts and joists have been left unclad in the interior and thus make the transition from structural element to building embellishment. Looking at the floor plans of “79 & Park” too it is noticeable that, as at “Norra Tornen,” very small spaces are extended by means of large windows and open-air spaces. The ceiling height of at least 2.75 meters additionally ensures more light and air.

In both projects the architecture studios have definitely lived up to their name. They have found innovative solutions for their building tasks – even adopting similar approaches on several points. This applies particularly to the modularity. Reinier de Graaf and OMA are slightly more consistent in pursuing this approach in their project, because they include the principle of prefabrication. That said, BIG has recently realized an affordable housing development in Copenhagen’s Dortheavej neighborhood in which the prefabrication of large elements likewise played a key role. This kind of construction is set to gain enormously from the fact that Ingels and de Graaf are showing what aesthetic potential it has. The same goes for the in part highly pragmatic and efficient layouts, which prove that less space does not necessarily mean having to go without – when, as here, the space that is lacking can be made up for with large windows and balconies, for example.

Incidentally, OMA’s and BIG’s concepts have also taken the housing market by storm. In both projects all the units had been sold well in advance of completion. “Norra Tornen” is to get a counterpart on the opposite side of the street, for which construction work recently began. And the project developer is already planning the next coup for Stockholm: Herzog & de Meuron is currently finalizing its plans for a new residential tower.

The twin towers "Norra Tornen" in Stockholm/Sweden by Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA) were recently awarded the International Highrise Award (IHP) 2020.