Up, up and away

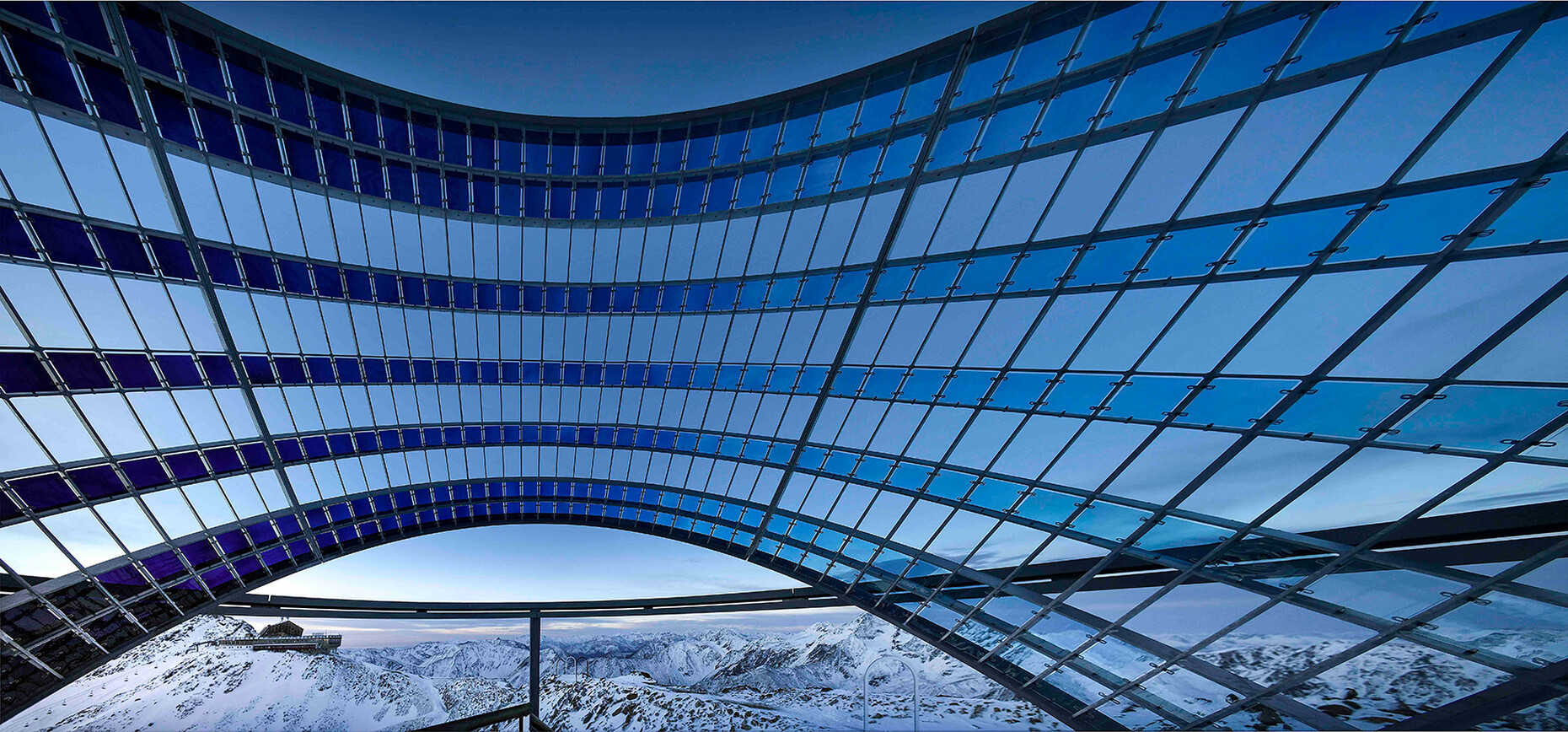

It is the very first work by Olafur Eliasson in North Italy’s Alto Adige region: In October 2020, the German-Danish artist personally opened a walk-through installation called “Our Glacial perspectives” at an altitude of 3,212 meters on the Grawand ridge above the local ski slopes. Together with the 410-meter-long pathway of contemplation leading to it the installation is effectively a journey in time. The overall intention is to sound an alarm about the disastrous state of the glaciers using an armillary sphere – a metal ring with 700 blue glass panes. “The idea goes back to the cyanometer by Horace-Benedict de Saussure, an Alpinist, scientist and philosopher who developed this instrument at the end of the 18th century to measure the color intensity of the sky. It served to better understand the future. An armillary sphere is the three-dimensional depiction of an astrolabe, previously called a model of the universe. It was used to depict movement. These devices help us to depict abstract ideas such as climate change,” Eliasson explains.

Like a pilgrimage, the path leads from the summit station of the Schnalstal Valley cable car, which is also the site of the Glacier Hotel Grawand, through nine archways that stand for the periods of the ice ages and makes straight for the blue spheres. Something like a calendar or sundial on which you can measure by the rings the time until the next summer or winter solstice. This is the rational explanation of the artist whose oeuvre has always revolved around physical natural phenomena. At the emotional level Eliasson wishes to convey to us that “we are not here to consume the world or for competition, but in order to cooperate.”

It took four years before the specially founded “Talking Waters Society” initiated by Ui von Kerl was able to realize the project, which had a price tag of around one million Euro. Kerl is also an artist and comes from Salzburg. He says: “Rather than moving mountains we wanted to install art on mountains.” Up here “a kind of chapel has been created in a sustainable manner because the components were transported without a helicopter.” His intention: “It is about demonstrating how small we are here in this very second.” While Eliasson’s work permits various interpretations, there is no ambivalence at all about the new viewing platform on the other side of the summit station: An almost free-floating suspended oval balcony intended to prompt people to recognize more clearly the exposed nature of the main Alpine ridge. Built by noa* - network of architecture under the supervision of Andreas Profanter, the bold platform called “Ötzi Iceman Peak” covers some 80 square meters and is enclosed by vertical blinds of weathering steel that, depending on your position, reveal ever new views of the surrounding mountains that are over 3,000 meters high. The existing summit cross was integrated into the planning. From here you look out at numerous summits, the place Ötzi was found am Tisenjoch – and over to Eliasson’s blue timeline spheres.

Modern architecture in the Alps polarizes. Without fail. Contemporary objects in Alpine regions are sure to attract critics whether for the sake of airing criticism or from genuine concern about ecological aspects or in protest at what they consider the visual 'ruining of the Alps' – although this is open to various interpretations. In Schnalstal Valley itself emotions ran somewhat higher because even Eliasson’s team only found out at the last moment about the viewing platform being planned to coincide with the installation. And irritation has also been caused by the use of Ötzi’s name and the Anglophone nature of the name. “The 'Ötzi' mummy found nearby is being exploited to market a mountain peak,” argues Reinhold Messner, who was the surprise guest at a local supper with invited journalists. It is exactly 30 years since 'Ötzi' was found, a find that continues to garner a lot of attention for the remote valley. While Messner appreciates the artistic approach of Eliasson his criticism is directed once again at Athesia, a publishing house in Bolzano, meanwhile the largest publisher in Alto Adige and a conglomerate. And: Today, 'Athesia' is the sole owner of precisely the Schnalstal Valley cable cars to the Grawand ridge. That suggests the following strategy: Are the architectural projects of Eliasson and noa primarily intended to ensure the cars are sufficiently used because they attract new visitors and strengthen the summer season given that the glaciers will disappear in the foreseeable future? Is this investment being made in art and architecture simply in order to remain relevant as an alpine tourist destination?

On the other hand: How would the remote valley that is sometimes described as “forgotten”, fare without these economic factors – like cable cars, the tourist site of the Ötzi mummy and new attractions from art and architecture? What would be the alternative to ambitious architecture campaigns by the cable car owners? “Calm. Quiet. Good cuisine. Like I have always said it is about the encounter between man and mountain,” adds Messner. But the outstanding mountaineer who resides at the valley entrance in the restored Juval Castle, is well aware that the genus of “independent Alpinist” is dying out just as are the glaciers in the region. In the Instagram age tourists want to experience a lot in a short time, ideally without much effort on their part and happily avail themselves of aids to their ascent. This brings us back to the benefits of cable cars and businesses also as a means of creating jobs and preventing young people in the valley from making for the cities. Currently, noa* - network of architecture are planning an entire resort at the lowest cable-car station in Kurzras. This balancing of interests and the struggle for architecturally fitting and sustainable solutions as well as seeking to harmonize economic interests, progress and an awareness for the environment will – just like climate change – only intensify in years to come.