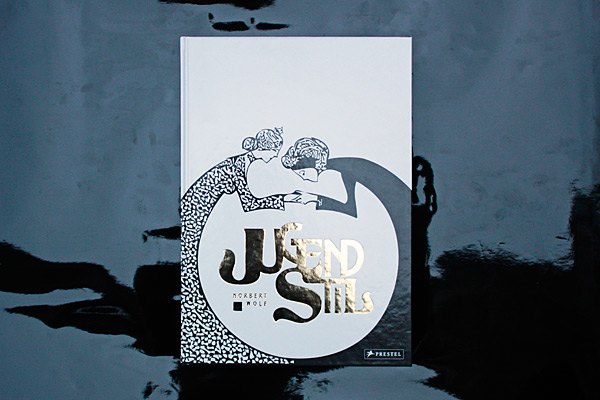

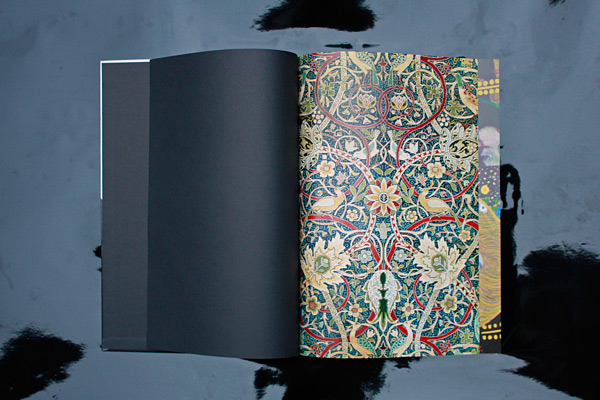

Only recently I read the first 20 issues of the German magazine “Jugend” launched in 1896, and which thanks to modern technology can easily be viewed on the Web; after all the German term for what elsewhere is known as “Art Nouveau” or “Modern Style” stems from this programmatic artist magazine. Almost everyone has a more or less clear concept of Germany’s “Jugendstil”: floral forms, wonderful two-dimensional ornaments, elegant opulence. Everything has already been said a thousand times or more about failed utopias, the fusing of art and applied design, about the synthesis of the arts – we have heard it all before. Which is why “Jugend” made such refreshing reading, after all, suddenly here you could sense the beginning, the enthusiasm and openness of the actors. From the very start the team behind “Jugend” called on readers to submit illustrations and texts, there were competitions and a double-spread “poster” at the middle of every issue . Seem from today’s perspective “Jugend” seems to me like a so-called “Fanzine”, a motley artist magazine, which right from the start somehow conveys what it does not want and consequently arrives somewhere else. Namely as the name for an entire style. There is a lot of joking in “Jugend” about the then latest invention, X-rays, women on bicycles are another source of amusement and there are many slight digs at the establishment, such as a report about an art academy on Mars where everything still runs as the academic folk want it. On the back page the reader then finds advertisements for artists’ material, terribly romantic hotels in Switzerland and repeatedly also for “Dr. Hommels Haematogen”, a tonic that was much hyped back then, derived from bull’s blood and supposedly helped cure anemia, a weak constitution, rickets and innumerable other unpleasant ailments. At some point (as we all know) the “Jugend” adjusted to accommodate the upcoming nationalistic spirit – and all understanding ends there. Yet the first issues of this magazine were like a key to an old, wonderful chest that has been locked for ages. I love Jugendstil, indeed the turn-of-the-century, a time that was so rich and exciting culturally, and I find it really regrettable that so little of it was incorporated into our contemporary architecture and “modern” design. Simplicity, the omission of decoration and an emphatically objective functionality have evidently won the day. Adolf Loos and Le Corbusier are the founding fathers of the immense cubes and boxes in which people sit today in front of small cubes and boxes and design still more cubes and boxes. Meanwhile, these gigantic workplace boxes are naturally made of glass, there is no longer any place for retreat, no decoration relates anything, no gaze lingers, you function in a functionalist architecture. I often imagine what a modern world would look like in which the architects, designers and artists of Art Nouveau were the heroes of contemporary architects and designers. It would be wonderful! You would walk through large ebony peacock gates into florally decorated, elegant high-rise palaces, travel by single-track bird-shaped trains through stony Palm tree forests and spend money in cavern-style shopping malls with colored, shimmering glazing. Surely the sticking point of Art Nouveau is that many of its designs are so fanciful, so startlingly visual, esoteric and consequently so dominant that they leave little space for anything else. It is a radical, effusive style, a break – as indeed it was intended to be. Yet I at least delight in traveling at least in my mind into an imaginary world in which Hector Guimard, Alfons Mucha, Joseph Maria Olbrich, Gustav Klimt, Fernand Khnopff, Aubrey Beardsley and James Abbot McNeill Whistler have designed every house, every door knob, every car and every technical appliance. The very idea is such a sumptuous feast, such an elegant and opulent enjoyment that waking up in our box world can happily be postponed until later. Today, there is only one modern domain in which the utopian worlds of Art Nouveau are still regularly cited: in Hollywood fantasy movies. Anyone who watches “Lord of the Rings” joins Frodo the Hobbit after a few gloomy turns in entering the bright elven kingdom, constructed by ingenious set designers from innumerable pieces of the grand Art Nouveau puzzle. In many fantasy films the world of the “good”, the pure souls and gentle helpers, stems from the models of Art Nouveau artists from the last century. That is where Art Nouveau can be found today, in the world of cinematic fairies and elves, as stage sets that are filmed, inhabited by fictitious creatures that typically likewise originated in the turn-of-the-century literature. So it does still exist after all, in our dreams of Arcadia, in fairy-tale books and fantasy movies, and that is also a reality, so maybe one day someone will wake up and say: That’s how I want to build. Go on! Off we go! But to avoid the outcome being another batch of well-meant kitsch á la Hundertwasser we are recommended to learn enthusiastically from the very much more radical elegance and beauty of the old heroes, say by reading the recently published and magnificent work “Jugendstil” by Norbert Wolf. This large-format book featuring almost three hundred pages shows once again how it was, and – as far as I am concerned – how it could be again today. It is a real pleasure! Jugendstil

By Norbert Wolf

Hard cover, 304 pages, German

Prestel, Munich, 2011

Euro 59

www.randomhouse.de