Column

In the Dior Jungle

The Kaufhaus des Westens is certainly the most famous of Berlin's many department stores. Its history goes back to the Berlin merchant Adolf Jandorf, who had the upmarket wishes of a wealthy clientele in mind when he opened the huge department store on Wittenbergplatz in 1907. For this purpose, Jandorf had the experienced department stores' architect Johann Emil Schaudt build a five-storey building with 24,000 square metres of sales space at the eastern end of Tauentzien. Schaudt developed an ultra-modern building of reinforced concrete and wide, open floors, but hidden behind a heavy natural stone façade of Wilhelmine classicism with a high mansard roof. It was the time around the turn of the century when the big department stores in Berlin were booming and - especially on Leipziger, Wilhelm and Oranienstrasse – ever larger and more magnificent palaces were springing up. The KaDeWe now attracted the public to the West for the first time. Only with it did the transformation of Tauentzien and Kurfürstendamm from residential to lively shopping streets begin. The opening of KaDeWe was therefore also the birth of "City West".

Today, KaDeWe still enjoys the good reputation of a traditional luxury department stores' offering upmarket products at upmarket prices. However, little has remained of the former splendour of its architecture: its heavy facades look old-fashioned and the interiors have been repeatedly rebuilt, extended and altered to squeeze ever more retail space into the building's shell. With an extension to the rear, the department stores' now covers not 24,000 but over 60,000 square metres on six and a half floors, if you count the sprawling restaurant floor in the attic. At the same time, most of the windows and balconies of the old KaDeWe building have been closed since the 1980s, turning it into a completely indoor world and making orientation in the labyrinthine interior even more difficult. Many a visitor despaired trying to find an exit in this endlessly glittering merchandise wonderland - or even just the bathroom.

Something had to change. This was also clear to Tos Chirathivat, Thai department stores' king, who was able to acquire a majority stake in KaDeWe's operations from René Benko's multi-layered Austrian Signa Holding in 2015. Chirathivat is regarded as an enthusiastic department stores' magnate from one of Thailand's richest families who focuses entirely on the luxury segment. The family came to Europe in 2011 with the purchase of the 150-year-old Milan department stores' "La Rinascente" right next to Milan Cathedral. Later followed Illum, which some say is the most beautiful department stores' in Copenhagen. And in 2015, KaDeWe followed in a package of German luxury department stores that also includes Oberpollinger in Munich and Alsterhaus in Hamburg. The business now belongs to the Chirathivats, while the properties themselves continue to be owned by Signa. The three properties are being developed jointly.

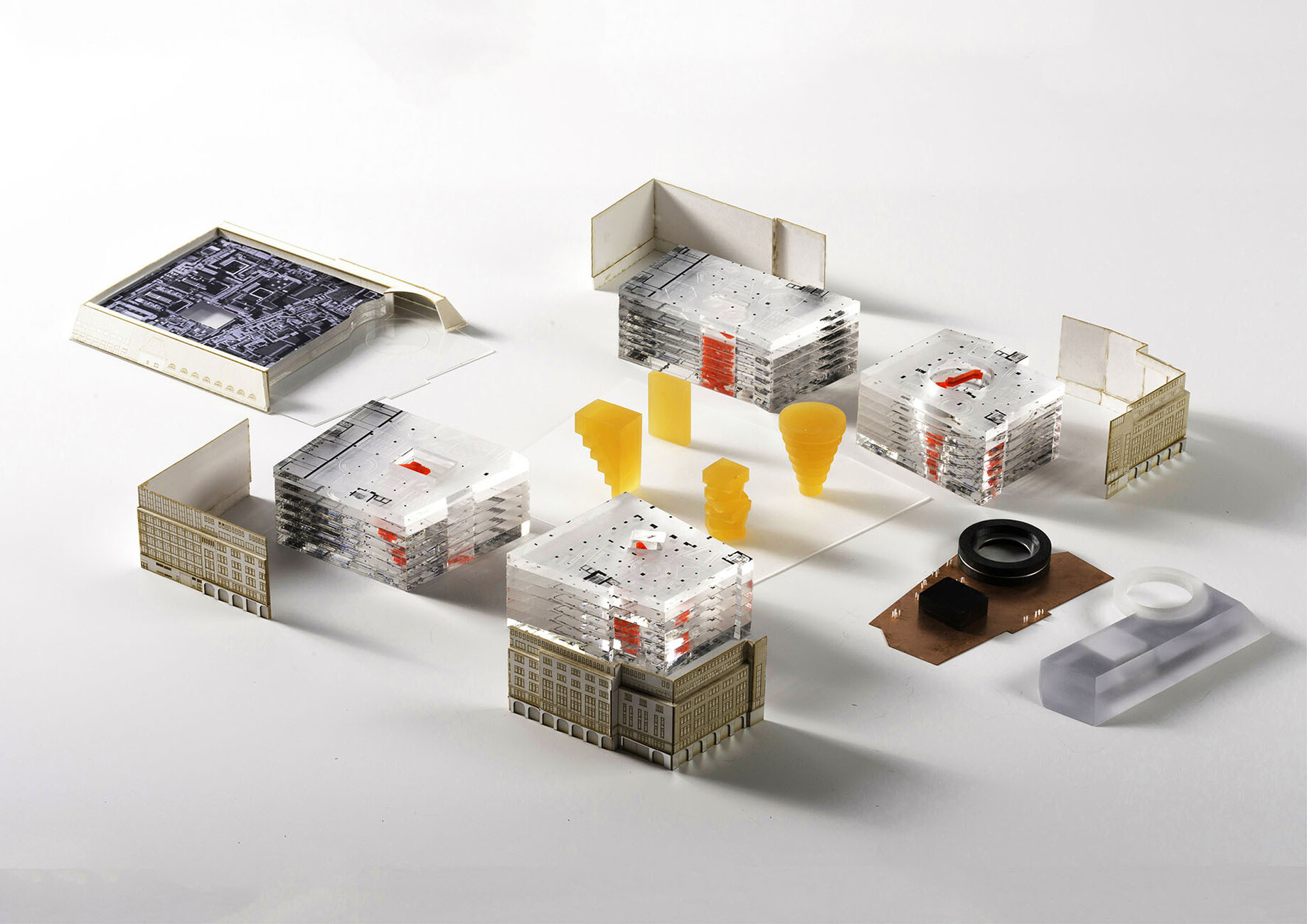

These developments were quickly set in motion. The British architect John Pawson was hired for the Oberpollinger, the Berlin-based Kleihues + Kleihues for the Alsterhaus and the Dutch star architect and Pritzker Prize winner Rem Koolhaas with his office OMA for the KaDeWe. (The fact that an OMA is responsible for the KaDeWe of all things opens up ideas for a good dozen corny jokes, but we won't go into them here). In fact, however, the KaDeWe was probably the hardest task assigned to OMA; this is also reflected in the fact that only about a quarter of the ambitious plan has been realised so far.

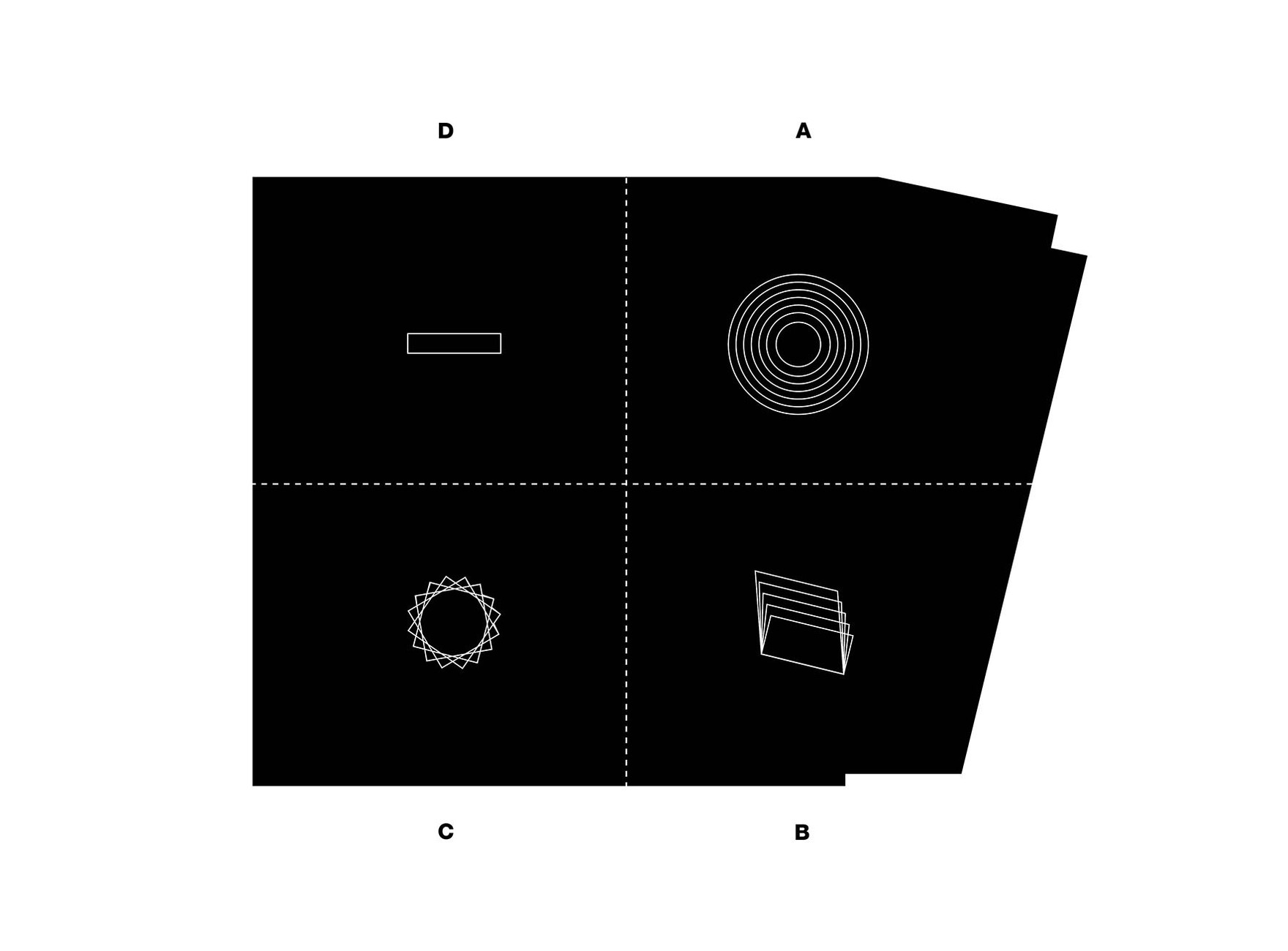

Because KaDeWe has been increasingly hollowed out over the years, so that it is now really just a shell with a renowned name. Inside, all the space is fully let to several hundred different brands, retailers and operators. OMA developed a variety of ideas for a better orientation and overview inside, as well as for a renewed opening of the building to the outside, to the city. For this purpose, two new main axes like inner streets are to be laid through the building on all floors. These new main streets will then create four so-called "quadrants", which will use different materials and styles to form clearly separated zones. In the centre of each of these quadrants, the architects of OMA place a separate, sculptural escalator system: four escalators, with which a new, strong identity is to be created in each quadrant. The inner infinity is divided into four parts, so to say.

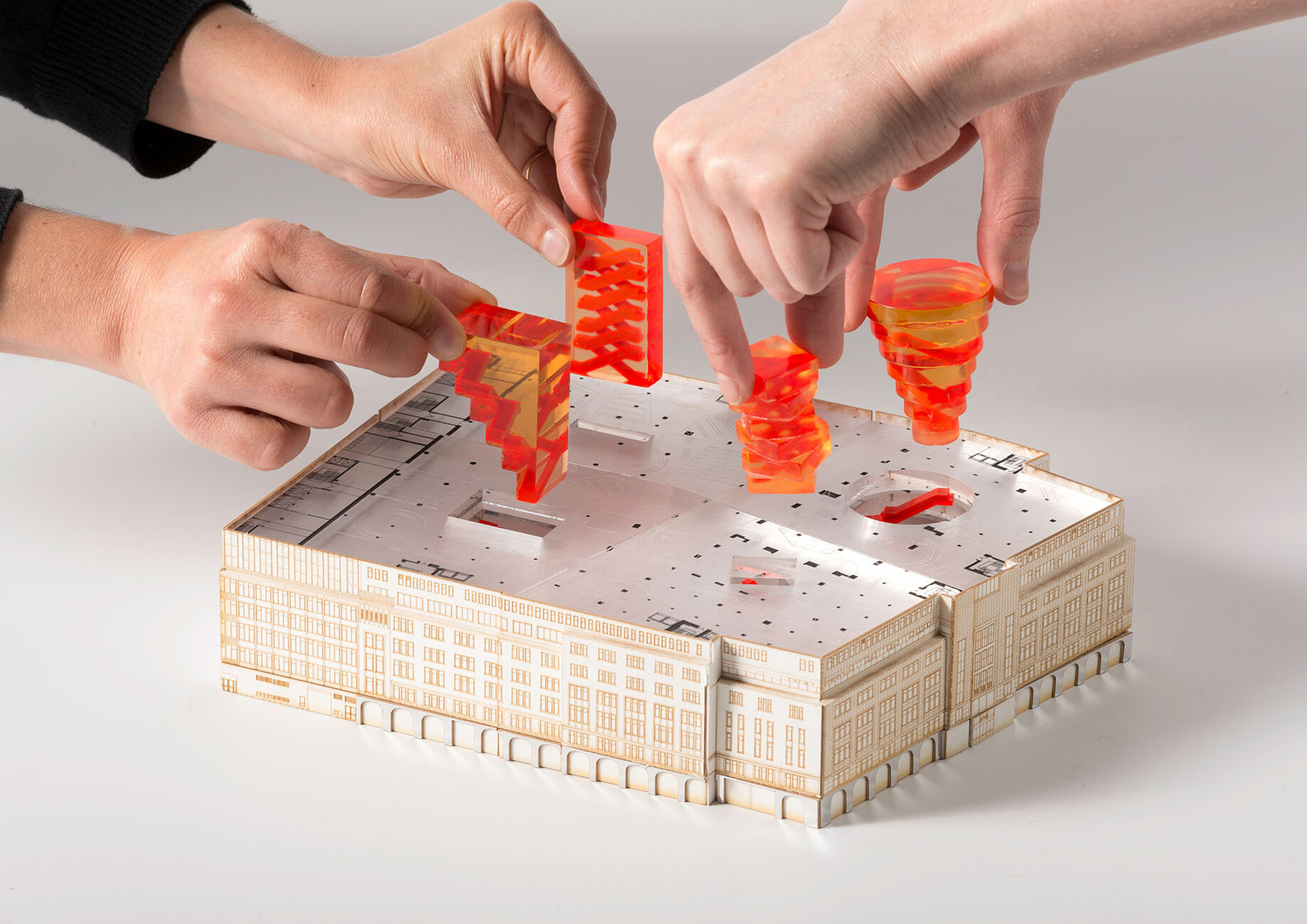

That is a convincing master plan. Now, however, the brands and retailers in the building still have to be convinced, and that takes time. Wherever parts of the plan are to be implemented, the tenants demand a say in the design of their spaces and equivalent replacement spaces for the time of the conversion. The work in the house resembles an urban master plan to create streets, paths and squares between areas where the users can design their spaces largely autonomously. Ellen Van Loon, the partner at OMA responsible for the project, speaks of an "architecture of negotiation" in which the quality of the implementation depends above all on the conviction of all those involved. This is often the work of a curator rather than an architect. One could probably also speak of a struggle for control: "We can create design guidelines for the quadrants, but whether they are actually taken into account depends on the negotiations between us, KaDeWe and the brands themselves." But they often have their own ideas, and the more renowned the brand, the less it wants to deviate from its own design ideas.

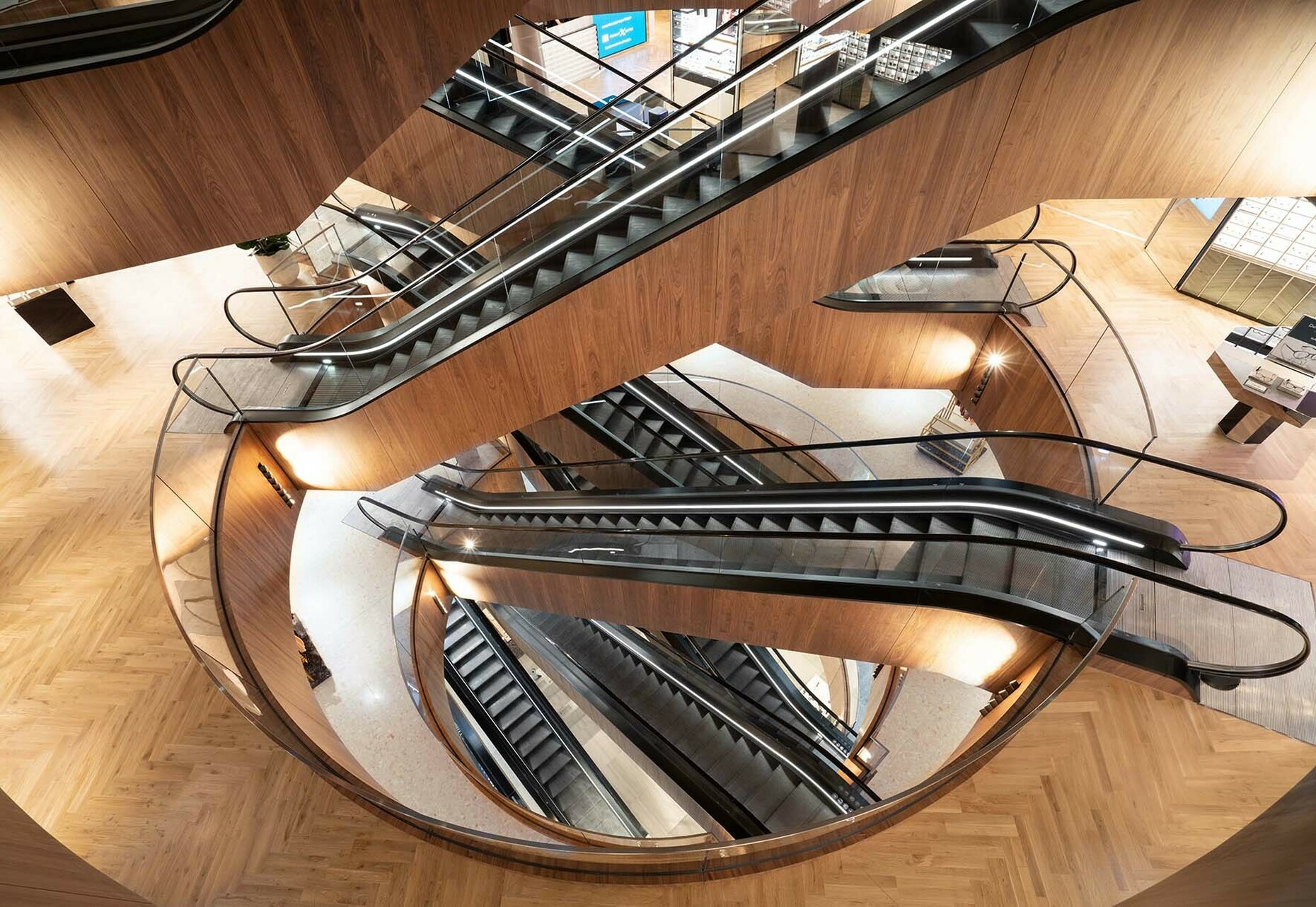

So the first quadrant was officially opened at the beginning of October; moreover, the ground floor has already been largely redesigned and the top floor is being worked on diligently in order to complete it before the Christmas business. And indeed, the first new escalator, "The Spiral", is an impressive sculpture in itself. Its individual flights of stairs, clad in warm oak, are slightly offset from each other on each floor, so that from below they resemble a stack of Mikado timbers or a strange, large flower growing in this circular atrium. Riding this escalator is also a joyful endeavour, not only because of the changing directions, but also because the other customers on the opposite path seem to keep meeting you from different directions. Unlike in other department stores, says Ellen Van Loon, these staircases in the four quadrants are not only intended to be technical installations for the most efficient customer transport. In KaDeWe, the moment when the customer changes from horizontal to diagonal movement through the department stores' is to be celebrated.

So the three escalators that will follow should also offer such festive moments. Next, the second quadrant will be tackled, that is the north-eastern corner of the building. In its centre will be a staircase called "The Twist", inside which a large air space will be created like in a tornado. This will be followed by "The Cascade" and "The Technical" in quadrants three and four. Van Loon does not know when these works will be completed. The KaDeWe press spokeswoman speaks optimistically of two more years, then the new KaDeWe should be completely finished.

But until then, there will probably have to be some negotiations with all those involved. On the day of the opening of "The Spiral", Ellen Van Loon stood at the foot of these beautiful new escalators, disillusioned, and had to realise that the space she had actually wanted to keep free around the escalator was already densely populated by luxury brands and their products. And we were able to learn: Basically, KaDeWe functions like a jungle. Because as soon as a little free space is created in one place with machetes and axes, it grows over again – except that no creepers grow here, but instead a dense undergrowth of perfume bottles from Chanel, Dior and Nina Ricci. The labyrinthine interior has all the charm of a wild adventure. And who knows how many ambitious architectures have been lost in this jungle?