A connection to Mies

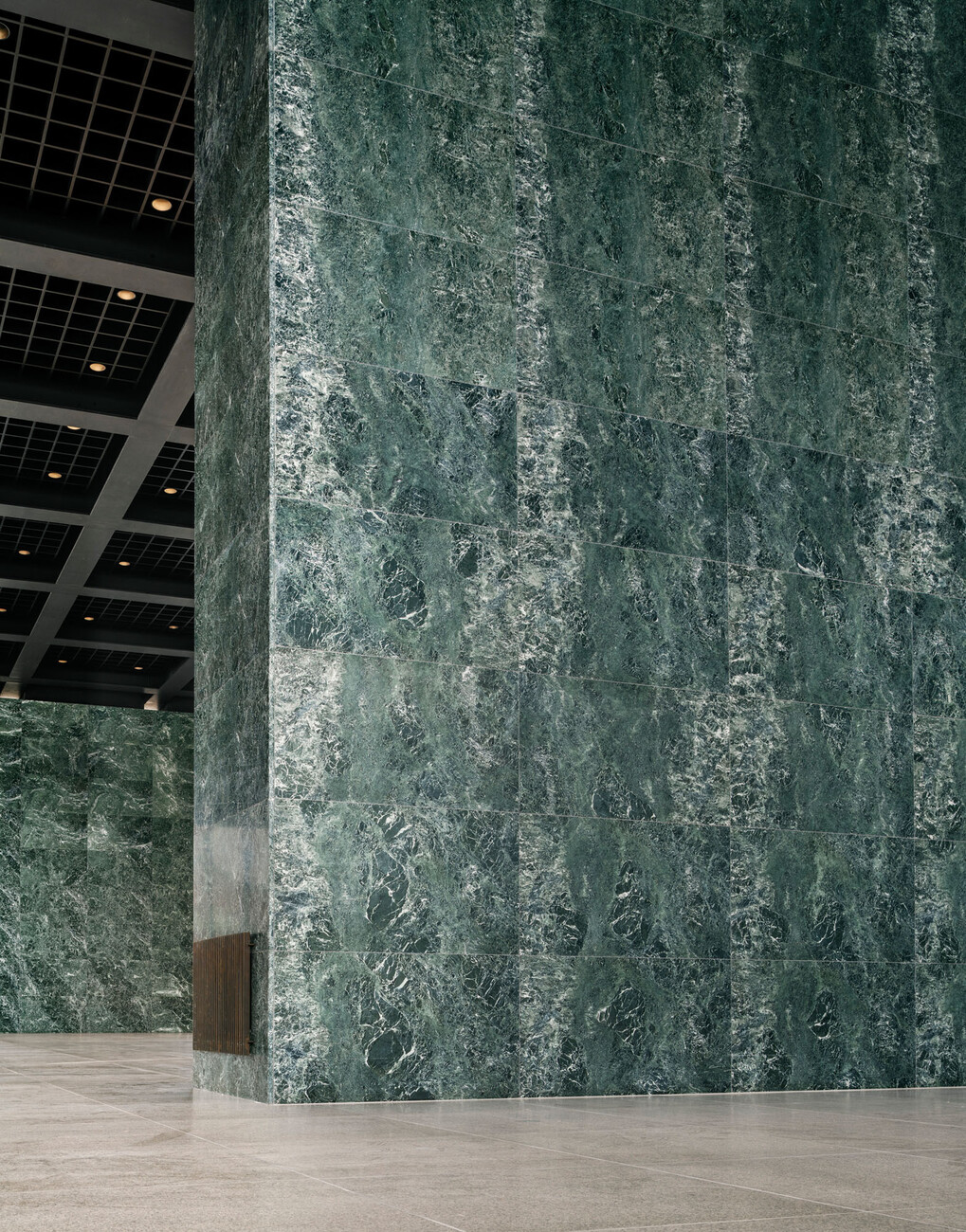

Mies van der Rohe’s Neue Nationalgalerie is a 20th century icon. Erected between 1963 and 1968 in Berlin, the museum is the architect’s only project in Europe completed after his emigration to the US. Correspondingly, David Chipperfield Architects approached the task of submitting the “temple of Modernism” to an extensive remodel 50 years after its construction with the appropriate respect. The job involved not only restoring and strengthening the existing structure, but also improving accessibility and the functionality of the cloakroom, café and museum shop. Furthermore, new technical solutions were added in terms of air conditioning, artificial lighting and security. Overall, around 35,000 original components were disassembled, including the natural stone slabs in the base segment as well as all parts of the interior.

Alexander Russ: What was the clients’ brief for the renovation?

David Chipperfield: The brief was not very detailed, but of course the task was very clear: the building needed to be repaired and restored, without big changes being made. That’s why the client was very anxious that anybody taking on the task would not challenge Mies.

Why did they choose your firm?

David Chipperfield: I think we were selected because of our experience of working on Neues Museum and the Museum Island in Berlin. We have a long-standing working relationship with the Berlin State Museums (Staatliche Museen zu Berlin) and the Federal Office for Building and Regional Planning (Bundesamt für Bauwesen und Raumordnung). A restoration project needs to reconcile contradictory requirements: the historians obviously want to protect the design; the technicians want to improve the performance. As an architect you don’t want to do this by seeing who is stronger. So, you try to find mediating solutions. Our long-standing experience of working on the Museum Island meant that the clients understood our method of leading, listening and mediating solutions, which comes from a good understanding of the complexity involved.

Which state was the building in when you started the whole process?

David Chipperfield: Superficially it didn’t seem so bad. The building has three parts: the temple, which is the most visible and identifiable element, the plinth, which is the hard-working piece, and the garden, which is an oxygenating element in this triangle that allows the whole thing to work. This little ecology of three elements works together in a very clever way. The spaces in the plinth are fairly mundane in themselves but together with the temple on top and the garden on the side it all performs very well. Going back to your question, I would say that the temple – the most public element – was not in a bad condition except for the obvious problems with the glass panes cracking. The glass was failing because the window frames were failing. While they did not look so bad, the frames were rusting from condensation and there was no accommodation for the expansion or movement of the glass throughout the seasons. But on the whole the temple didn’t immediately appear to be in a bad state.

And the rest of the building?

David Chipperfield: The real surprise to us was the poor condition of the spaces and the structure in the plinth. They were not very well built. Every time we took something up, we found additional issues. For example, we took the stone floor up and we found that the concrete was in a bad condition. Then we took the surface of the concrete up and found that the rest of concrete was in a bad condition. It was quite shocking to see how poorly this building had been constructed in the 1960s. And then again not surprising, given the economy and the situation of West-Berlin at that time. And all of a sudden, we realised that this poem by Mies van der Rohe, which is dedicated to technology and modernity, was actually built by hand.

Your team travelled to the US to visit buildings designed by Mies van der Rohe and to do some research in the archives of the Museum of Modern Art.

David Chipperfield: The team went to North America and looked at the condition of Miesian buildings 50 years later – how they had been restored or not restored, and what lessons we could learn from that. There was a lot of documentation and we had the support of Miesian experts including his grandson. So, the records of the project were good and really helped to inform the discussions.

Dirk Lohan, Mies van der Rohe’s grandson, was also the Project Manager of the Nationalgalerie when it was built. What impact did he have on the renovation process?

David Chipperfield: He brought in a great deal of deep understanding of the process and of course a lot of anecdotal stories that were also quite important. He was a bridge between the first time and the second time the building was built. At some point, when we were dismantling the building, it looked like a building under construction. For him this was some sort of déjà vu, except that he remembered the building going in the other way. His impact was very important for the team and for our memory and our ethos. It was good to have someone who acted as a guide of sorts.

As I was preparing for this interview, a lecture from when I was a student came to my mind. Back then, the professor showed us the 43 plans for the Neue Nationalgalerie and explained them to us. I remember that I was quite impressed by the architectural vision but also by the way this vision was presented. How did those plans affect the renovation process?

David Chipperfield: We often recognise buildings of that period through photographs, but with Miesian buildings you also know them by the plan. In the case of Mies, the plan is something that must also be protected conceptually. If you are restoring a 19th century building you also want to keep the spaces, but for the most part it’s an experiential discussion. So, if you have to make some changes to the plan because you need an elevator or a bathroom, I am sure you could build that in. It’s not easy and we tried to avoid it at the Neues Museum, but there were moments when it was possible. But with a Mies building it is not just about the experiential. His plans are almost like a Mondrian painting – like a piece of art. So, we tried to respect the plan as much as possible.

The architecture of the Neue Nationalgalerie is a skin and bone architecture where there is nothing hidden. At the same time, you didn’t want to leave your fingerprints on the building. How did this work?

David Chipperfield: The task was not to turn a Mies van der Rohe building into a David Chipperfield Architects building. The task was to bring Mies’ building back. There’s only room for one architect in this building. This may sound quite modest but it’s not – it’s obvious. There was not the slightest discussion about this point. The only crisis we had in formal terms was the reoccupation of some of the spaces for the cloakroom and the shop. How do you bring spaces that were not designed by Mies into the public space and what identity should those spaces have? I suppose that is the moment where we could have left our fingerprints. But we tried to find a solution where we engaged the construction of the building so you can see the raw spaces into which they are inserted.

Was this the most complex task?

David Chipperfield: The most complex task in technical terms was the glazing of the temple. This was a mediation between two positions. One was intellectual, following the idea that ‘God is in the detail’ and keeping the window frame exactly as it was designed by Mies. But then on the other end of this discussion is a technician who is saying that this construction doesn’t work. For it to work according to today’s performance standards, the window frame would need to be three or four times bigger. So we had two seemingly unresolvable conditions: protecting Mies or improving the performance of the building. Improving the performance was also part of the brief, after all. But again, I have to say that this mediation process is something that we really enjoy. That discussion in itself is just a wonderful discussion to have. And the solution that we found incrementally for the mullion of the window frame stays very close to the Miesian idea while still improving the performance. A key decision was to reuse everything that was already in the building. It would have been very easy to take everything down and replace it. You can get the stone again, you can get the metal again, you can get everything again. So why keep it? We felt that it was important to work with those pieces. It was our connection to Mies – a connection to authenticity.

Looking at the result, do you think you succeeded?

David Chipperfield: If you ask where our fingerprints would be, I would say they are only visible on any mistakes we have made. Fortunately, I think all you can see is Mies.