MICROLIVING

The final days

Even without seeing it, you can easily picture what the Nakagin Capsule Tower is like: You need only imagine two stacks of big, white washing machines piled up on top of a shared two-story podium of offices to the height of a tower. More precisely, they are pretty enormous washing machines: Each one measures 2.3 by 3.8 by 2.1 meters, and they rise up directly next to the Tokyo Expressway, the elevated urban highway, to heights of 11 and 13 stories. Needless to say, these are not washing machines at all, but rather residential capsules, and the two towers from 1972 are among the major works of Japanese Metabolism, an architectural movement that flourished in the 1960s and ’70s and aimed to create modules that could be assembled to create homes, houses, city districts and ultimately entire cities for future living. The modular construction would make it possible to repair or replace each unit individually, meaning people would no longer have to live in outdated apartments and could instead continually renew their home modules in line with the latest standard – the very epitome of an update. This would mean that buildings, like cities, could not only grow continually, but could at the same time be constantly renewed like plants – that was the idea behind Metabolism. One of the main representatives of this movement was Japanese architect Kisho Kurokawa (1934-2007), who came up with the design for the Nakagin Capsule Tower.

Anyone not content with merely imagining these two capsule towers and wanting to actually visit them will have to hurry. Their demolition is apparently imminent. The owner, Japanese investment company CTB CK, has made preparations to buy out the 40-odd remaining capsule owners and the last 20 permanent residents of the tower moved out of their capsules in April 2021. This will now enable the CTB to demolish the structure, which is not heritage-listed. It’s worth pointing out that the Ginza district where the tower is stands is among the most expensive locations in the city – and in Tokyo that is quite something. The Imperial Palace is just a stone’s throw away. When the Nakagin Capsule Tower was built in 1972, it was the only high-rise along the highway, as is clearly evident in photographs taken during construction. In the meantime, it has been tightly enclosed by equally tall, but by comparison banal office and housing blocks. The plot may well be very valuable, and it will be even more valuable when it’s empty and can be developed to maximum effect. The capsule tower is quite simply in the way.

What’s more, after years of neglect it is now decidedly run down. The steel structure is rusting, the plumbing is leaky, the load-bearing structure contains asbestos and, since one of the large round windows fell out, a safety net has been hanging around both towers. While around 80 capsules were still in use until recently as offices, hobby spaces or second homes, around 40 capsules have been unoccupied for many years, and in fact weeds are actually sprouting in some of them. If the building were to be saved, all the capsules would have to be dismantled, the core structure thoroughly redeveloped, and ultimately all fully renovated capsules assembled anew. The cost of a renovation faithful to the original is estimated at 75 million euros.

The owner has been contending for a good 20 years now that the tower is not economically feasible. The fact that the building is still standing at all can be attributed, on the one hand, to the complexity of its ownership structure, and on the other to the global economic crisis post-2008: All 140 capsules were sold one by one to private individuals, while the load-bearing structure and the plot belong to the owners. The CTB has therefore had to seek majority control of the building by buying up capsules, while at the same time attempting to gain a majority consensus among the remaining private owners for the demolition and sale of the plot. In 2007, it was able to garner the necessary 80-percent majority for the first time, but the onset of the global economic crisis thwarted realization of the plans. It seems economic crises can be good for something!

Now has come the second and what is most likely to be the final attempt. In November 2020, the CTB again bagged the 80-percent majority of the votes it needed. In the intervening years, an owners’ initiative led by the enterprising Tatsuyuki Maeda, who owns 15 capsules himself, had tried in vain to find an investor who would buy the building and invest in its renovation. Maeda says there were various meetings, but ultimately they were unable to find a business or private individual willing or able to put up the money. At the end of the day the costs were too staggering. The Japanese government was likewise uninterested; Maeda says there is little enthusiasm for post-war Modernism in Japan. And have you ever tried to raise 75 million euros via crowdfunding?

The paradox of the current situation is that from Day One Kurokawa envisaged replacement of the residential capsules. “If you replace the capsules every 25 years or so, then the building could undoubtedly last for 200 years,” he wrote. Each capsule is attached to the core structure by just four bolts. The size of the standardized capsules is based on the dimensions of four tatami mats like those found in traditional Japanese tea pavilions. Larger modules could also be attached to the connection points, hence a young couple getting to know each other could attach one larger capsule in place of two individual ones, and perhaps later, who knows, an even larger family capsule. Yet this never actually happened. The capsules that hang on the structure today have been there since 1972. The building never actually started to “metabolize” as envisaged by its inventor.

The ideas of placing the building under heritage protection have thus far led primarily to highly complex technical discussions: In what state should one preserve a building when the fundamental idea behind it is constant change? Opinions differ on this and so the building is still not listed, and an application to become a UNESCO World Heritage Site, be it intangible or material or somewhere in between, has likewise failed to find a backer. And these applications first and foremost require funding.

One thing is certain: The value of the Nakagin Capsule Tower should also be measured on the fact that it is one of the few Metabolist projects that actually saw the light of day. Any doubt about the contemporary value of such a building likewise seems unfounded: The few inhabitable capsules have been hugely popular right to the end, both with long-term usage and, of course, as short-term holiday lets for a really special Tokyo experience – in a washing machine! The English-language tours that “Showcase Tokyo” offered of the tower and some of the apartments until very recently tended to be booked out, while the captivating book “Nakagin Capsule Style”, published in late 2020, features 20 happy residents in their very individually furnished, generally chock-full capsules. At a time when there is much talk about “tiny houses”, a capsule tower like this, with contemporary fixtures and fittings, could actually slot very neatly into our society, regardless of the fact that doubtless nobody is envisaging megastructures for entire capsule cities any longer. Even the planned settlements on the Moon and Mars now no longer seem quite as tech-savvy and progress-obsessed as in the 1970s.

The CTB is refusing to comment on its plans. Tatsuyuki Maeda has ceased to believe the tower can be saved, since the costs of renovation are simply too high and the price of the plot too tempting. Nevertheless, he is aiming to rescue some of the original capsules, renovate them and put them on show. The final 30 capsules still in use are set to be removed in the summer. Maeda aims to launch a crowdfunding initiative for the renovation of a few capsules, since he no longer sees state funding as an option. So right now, it really does seem that Tokyo will very soon boast one less Metabolic masterpiece. The Nagakin Capsule Tower, sadly, has seemingly been put out to dry.

Book recommendations:

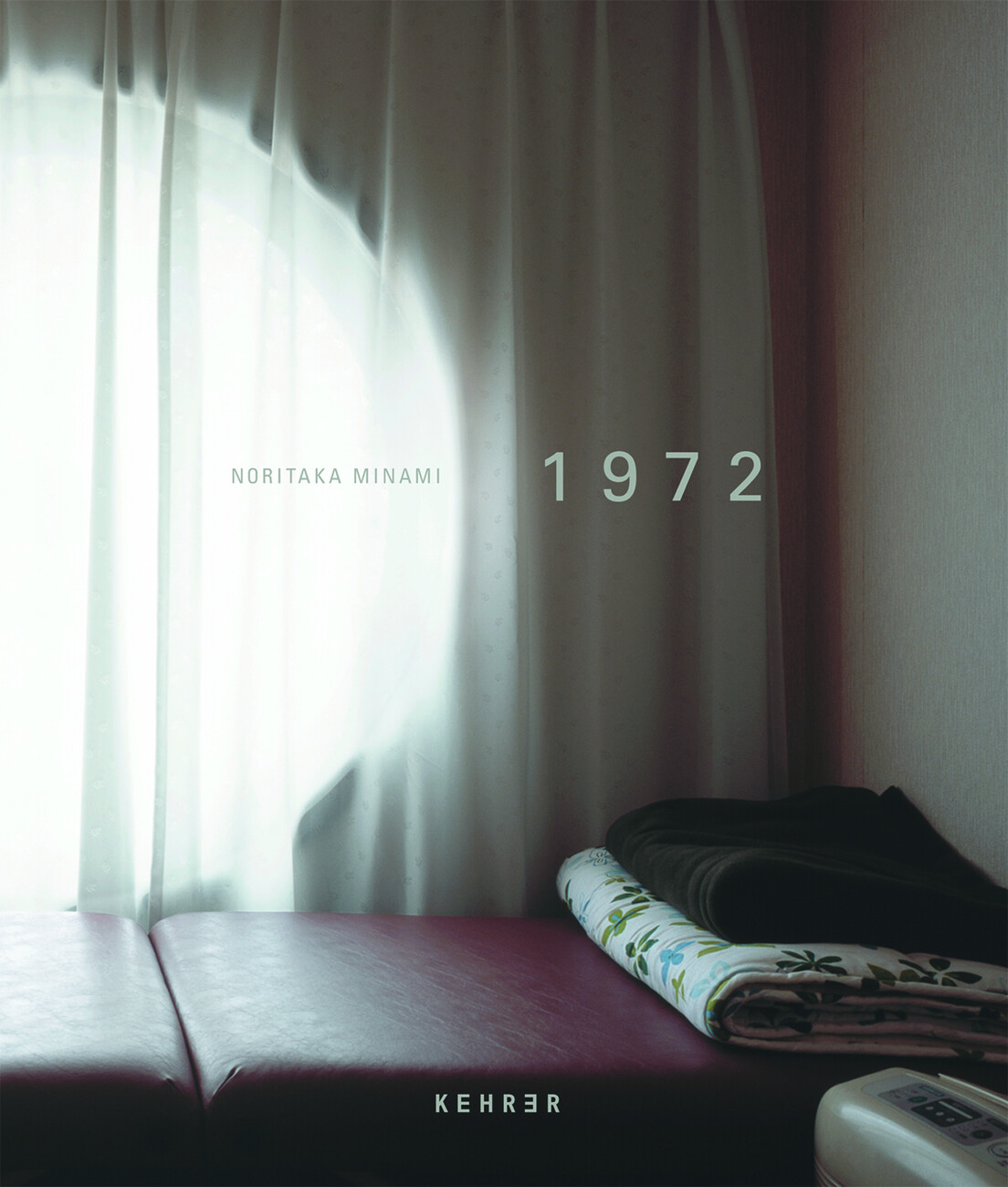

1972 – Nakagin Capsule Tower

Noritaka Minami

Texte von: Noritaka Minami, Julian Rose, Ken Yoshida

100 pages

54 colour and 1 b/w illustrations

Language: English

Publisher: Kehrer

ISBN 978-3-86828-548-2

34,90 Euro

Nakagin capsule Tower Style

Kisho Kurokawa

132 pages

Language: Japanese

Soshisha

ISBN: 978-4794224880

23,25 Euro