Respect for the beast

Eight years were needed by the television journalist and documentary filmmaker Hauke Wendler to realise his film about a special type of chair, a personal project. Perhaps this is also due to the subject matter, the white stackable plastic chair, that beast among seating furniture that is rarely beautiful, but practical, cheap and therefore in demand all over the world. Up to this point, Wendler has made films as a co-author with his colleague Carsten Rau about political circumstances and conditions in Germany, mostly dealing with flight and migration. Now, Hauke Wendler has switched from the political field to a cinematic educational journey around the world. In the 90-minute film "Monobloc", the white plastic chair is the protagonist, a piece of furniture with no design ambitions. "Monobloc" premiered at film festivals in 2021 and was released in cinemas at the end of January 2022. In the meantime, it has grown into a multimedia project, accompanied by a six-part NDR podcast in which Wendler talks about his international shoot and delves into aspects of the film. In addition, there is an illustrated book with over 190 pages, which will be published by Hatje Cantz at the end of February, the English version will follow in July 2022. Hauke Wendler seems equally repelled and fascinated by white plastic chairs. They exist all over the world, they are also present in places and non-places, they do not pay any particular attention to contexts. Can preconceived opinions, conditions and circumstances be presented and discussed using the example of a single, globally present object? A chair as a vehicle of enlightenment? That could be a motive for making a film about a chair.

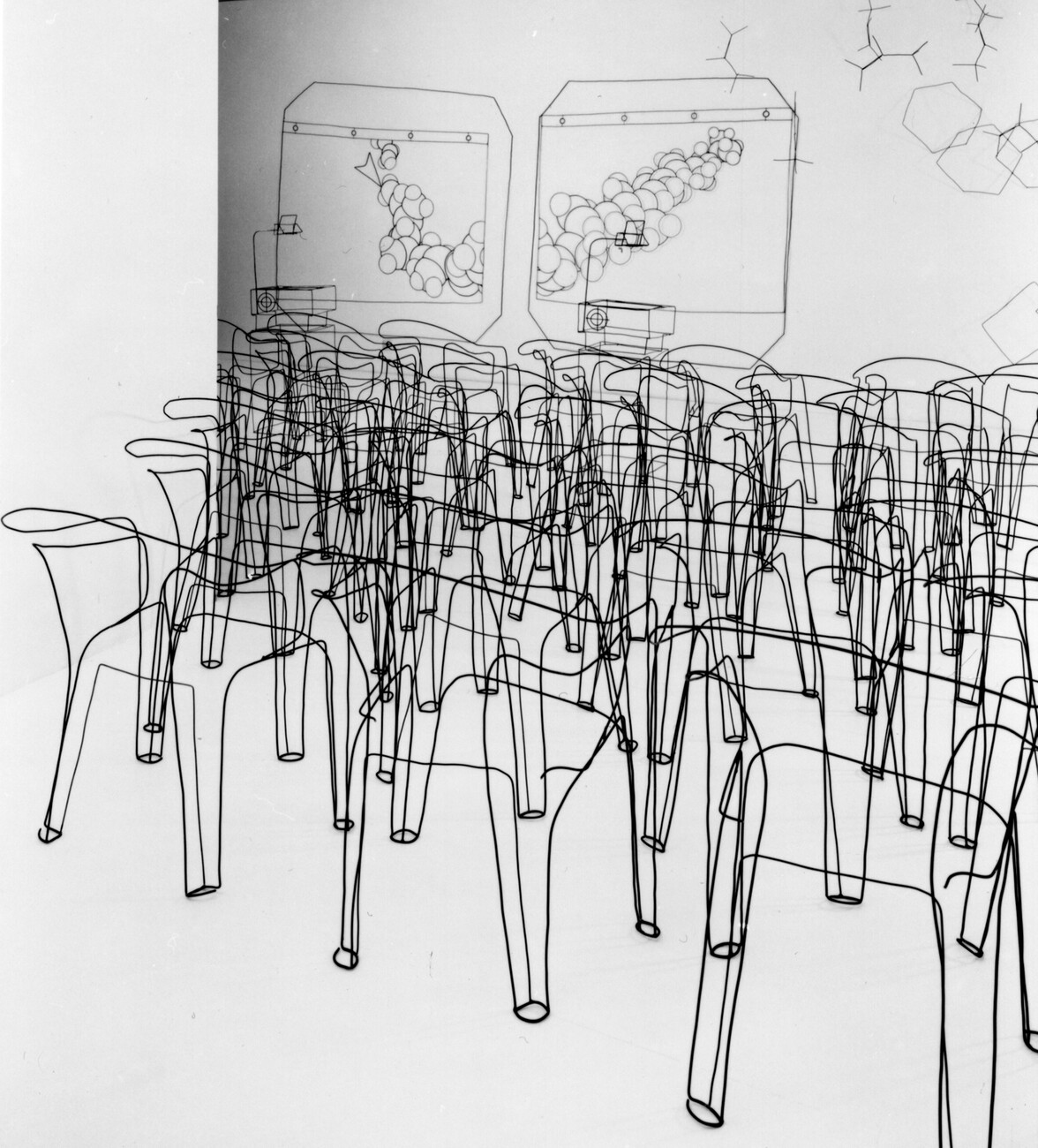

Hauke Wendler's 2016 project has barely begun when it already seems to be on the brink of failure. At first, no one wanted to promote his film, and several requests were rejected. But that's not all: with "Monobloc – A Chair for the World", the renowned Vitra Design Museum is dedicating an entire exhibition to this very type of chair. Could this draw attention away from his project, the director wonders? The small collection in the middle of the exhibition closes years before Hauke Wendler can complete his film. On the day the exhibition is dismantled, he shoots in Weil am Rhein. "Making chairs from a single piece of material," curator Heng Zhi tells him, "has fascinated designers for a long time." From one material and from one piece, one might add. Because experiments with different plastics initially led to furniture that was assembled from several small pieces or was simply smaller, as plastics technology initially struggled to master large forms. In the case of the "K 1340" children's chair by Marco Zanuso and Richard Sapper from 1964, as in the example of the "Universale" stacking chair by Joe Colombo (1965), the legs are manufactured separately and attached, an intermediate step on the way to the Monobloc. Kartell has brought both of them onto the market. Henry Massonnet's hyperbolically shaped "Tam-Tam" stool from 1968 also belongs to this series. Until the 1980s, the piece was sold 14 million times.

If all this were a topic for the documentary filmmaker, Jens Thiel would have to be mentioned now at the latest. He sat on the podium as an expert at the opening talk. The Augsburger Allgemeine's report on the Vitra exhibition says: "Whoever says Monobloc must also say Jens Thiel." He is the "supreme saviour and explorer" of this plastic chair. Hauke Wendler does not name him, except in the credits. Because a key document of Wendler's film is a film clip that comes from Thiel. Thiel had found out that Henry Massonnet was the first person in the early 1970s to succeed in producing robust plastic chairs from one piece in larger quantities. While Massonnet was still alive (he died in 2005), he visited him at his company STAMP in Nurieux, France, and got to see the small company museum under the roof, where the entrepreneur and inventor kept his most important pieces, such as the "Fauteuil 300", that central reference point in the history of monobloc design. Massonnet was not a designer, but created many of his furniture pieces himself. At times he worked together with Pierre Paulin. Massonnet had transformed his father's comb factory into an innovative plastics manufacturer, he collected art and was mayor of his community.

We learn nothing of all this in Hauke Wendler's film. For him, it would be enough if the seat, which is scorned in this country, were treated with a little more respect in future. His cinematic journey leads in episodes to the North Sea, to the efficient production facility of a northern Italian family dedicated to perfecting the Monobloc chair, to the Vitra Design Museum, to a designer in California who first built a plastic chair into single wheelchairs and distributed 1.2 million of them worldwide thanks to donations, on to India, where an entrepreneur plans the future of the plastic chair and explains that it made sitting affordable for the middle class in his country. Hauke Wendler also accompanies women waste collectors in Brazil, for whom a broken plastic chair is a particularly valuable find that brings in more than other objects and materials. Impressive are the pictures of men who sort broken plastic objects and cut them up with machetes to prepare them for recycling. Others wash the chopped-up secondary raw material so that it can be turned into granulate and then back into a plastic chair. It's about nuances, life plans, destinies that are condensed into a message: The white plastic chair is not quite as simple as expected!

For some it is: in Hamburg's Hafencity, the director stands on the loading ramp of a truck with a megaphone, an improvised film studio. There he motivates passers-by to express their opinions about plastic chairs and especially the "Monobloc". The results can be seen before the great journey begins. The negative comments are unanimous, their range is wide, which is possibly due to the fact that the audience is questioned on the way to and from the Elbphilharmonie. Those who comment feel that the chair is an imposition – aesthetically, practically, ecologically and also because it makes "no contribution to culture", as one particularly angry citizen puts it on record. One may even break a chair he brought along for the shoot. People speak here who can afford better. It is easy for them to detest the Monobloc, while everywhere else in the world it may not be revered, but at least it is needed.

Jens Thiel's approach is different. For him, the often anonymous white monobloc is the "best furniture in the world". This is also the title of a clever essay Thiel published in the magazine "Der Freund" in 2004, which clarifies the connections between technology, material and pricing. At that time, Thiel ran (until 2007) the English-language blog called functionalfate.org, which quickly became the most important international forum on the Monobloc chair and can still be found in web archives today. He sees himself as the originator of much of what happened around the Monobloc Chair in the media in the early 2000s. Thiel says of himself that he is someone who "makes big themes and then doesn't realise them." So he co-wrote the first business concept for Idealo and was active in the start-up scene before others had any idea what it even was. The artist Tina Roeder preceded his activities with her project "White Billion Chairs".

Hauke Wendler labels his Monobloc project "the best-selling chair in the world", and the publisher and film distributor add the superlative "of all times". A claim to absoluteness that comes to nothing. For the Monobloc is not a single chair with a circulation worth billions, but a type, a standard with an infinite number of variants, produced all over the world. At the same time, it is subject to permanent development and increased effectiveness. Jens Thiel once compared it to the white T-shirt. "It is the crown of efficiency of an industrial society," he wrote, "which has made our lives easy and harmless." Efficiency and price are the criteria, as Mateo Kries from the Vitra Design Museum makes clear in the film, with which this type of chair sets itself apart from all its competitors. It seems to have an unassailable advantage over others.

Talking of figures: by 1930 alone, Thonet No. 14, the bentwood chair that ushered in the era of designed industrial products in 1859 and found worldwide distribution as a coffee house chair, had sold 50 million copies. Since then, millions more have been made, and it is still manufactured today in Frankenberg, Hesse, as Thonet 214. And there is also data for the "Louis Ghost", a monobloc made of transparent polycarbonate designed by Philippe Starck for Kartell in 2002: In the twenty years since production began, the furniture, which is reminiscent of late Baroque models from the era of Louis XV, has been sold 20 million times. Unlike the mostly nameless monoblocs, this chair plays in the league of exclusive branded goods, which does not exclude mass production. Today, an example costs between 260 and 300 euros. What is interesting about the "Monobloc" is how it could become a kind of unbranded brand that does not want to stand for distinction, distinctiveness and prestige, but for usability in scenarios that are not further defined. In this respect – which the film and accompanying media unfortunately do not address – it is a stake in the flesh of a conventional understanding of design.

Admittedly, the filmmaker admires the colours of the innovative models that designers have come up with in the Vitra Design Museum. But their ideas interest him as little as the lines of development of the plastic chair. Nor does he pay any attention to the progressive lightening of seating furniture through new materials, starting with the dismountable Thonet chair made of bentwood and the French sheet metal chair of the 1920s, which are evolutionary precursors. It goes without saying that the film documentary "Monobloc" does not want to be and cannot be a history of design, but the fact that it largely ignores origins and developments makes the entire project questionable. Especially when facts are distorted by omission.

One of the most important stories Hauke Wendler tells is the connection between three people. There is the pastor Francis Mugwanya, who contracted polio at an early age and was not given a wheelchair until he was 12. His aid organisation "Father's Heart Mobility Ministry" provides wheelchairs to the needy. So far, he has been able to help tens of thousands to more mobility and a better life. Annet Nnabulime is one of them. The former shopkeeper, whose legs have been paralysed for years, lives at Lake Victoria. The young grandmother was dependent on permanent support from her family until she received a wheelchair from Mugwanya. The US Christian aid organisation "Free Wheelchair Mission" sent her a "Gen_1" and she is delighted with the freedom of movement she now has again. It was designed by engineer Don Schoendorfer, who over 20 years ago designed a wheelchair that should not cost more than 30 dollars. He bought the components at the local shopping centre. For the seat, the designer chose a "monobloc" chair with shortened legs, which already excited the monobloc community at functionalfate.org. In the meantime, however, the aid organisation's website states that the original model is "now retired". And one also learns there: the successor models "Gen_2" and "Gen_3" with a blue metal frame and without a Monobloc insert, which are lighter or foldable, were made in 2009 and 2013, i.e. before filming began. In the film they are shown without textual mention, in his book they are shown in one illustration.

How did Jens Thiel write in the 2004 essay? "The white of the monobloc invites us to use it as a projection surface for our own interpretations of the world, taking different directions depending on our preconceived intentions." Hauke Wendler has good intentions with his project. On his educational journey, we can look over his shoulder, perhaps become a little wiser. But the beast among the seating furniture is not so easy to get a grip on.

Addition: An earlier version stated that "just" Tina Roeder had dealt with the Monobloc chair before Jens Thiel. It can be mentioned that in addition, the artist Sibylle Hofter showed her exhibition "Aurora" (with accompanying book "Model: Aurora – 500 Million Plastic Chairs") in the Munich City Museum in 1997. Her 99-minute film about Monobloc chairs, which Hellmuth Costard helped to shoot and edit, appeared in the ZDF series "Das kleine Fernsehspiel".

Tip: On 19 February 2022 at 7 pm, "Aurora" will be shown at Berlin's Café Manstein (Mansteinstraße 4, Berlin-Schöneberg, Phone: 030 – 544 649 86). Attendance is possible according to current corona rules. Approximately 20 people can attend, early registration is recommended. If necessary, an alternative date will be organised.

Monobloc

Hatje Cantz Publishing House

Text(s) by Hauke Wendler, design by Rutger Fuchs

German

February 2022, 192 pages, 120 ill.

ISBN 978-3-7757-5187-2

22 Euro