MOBILITY

Shaping the mobility of tomorrow

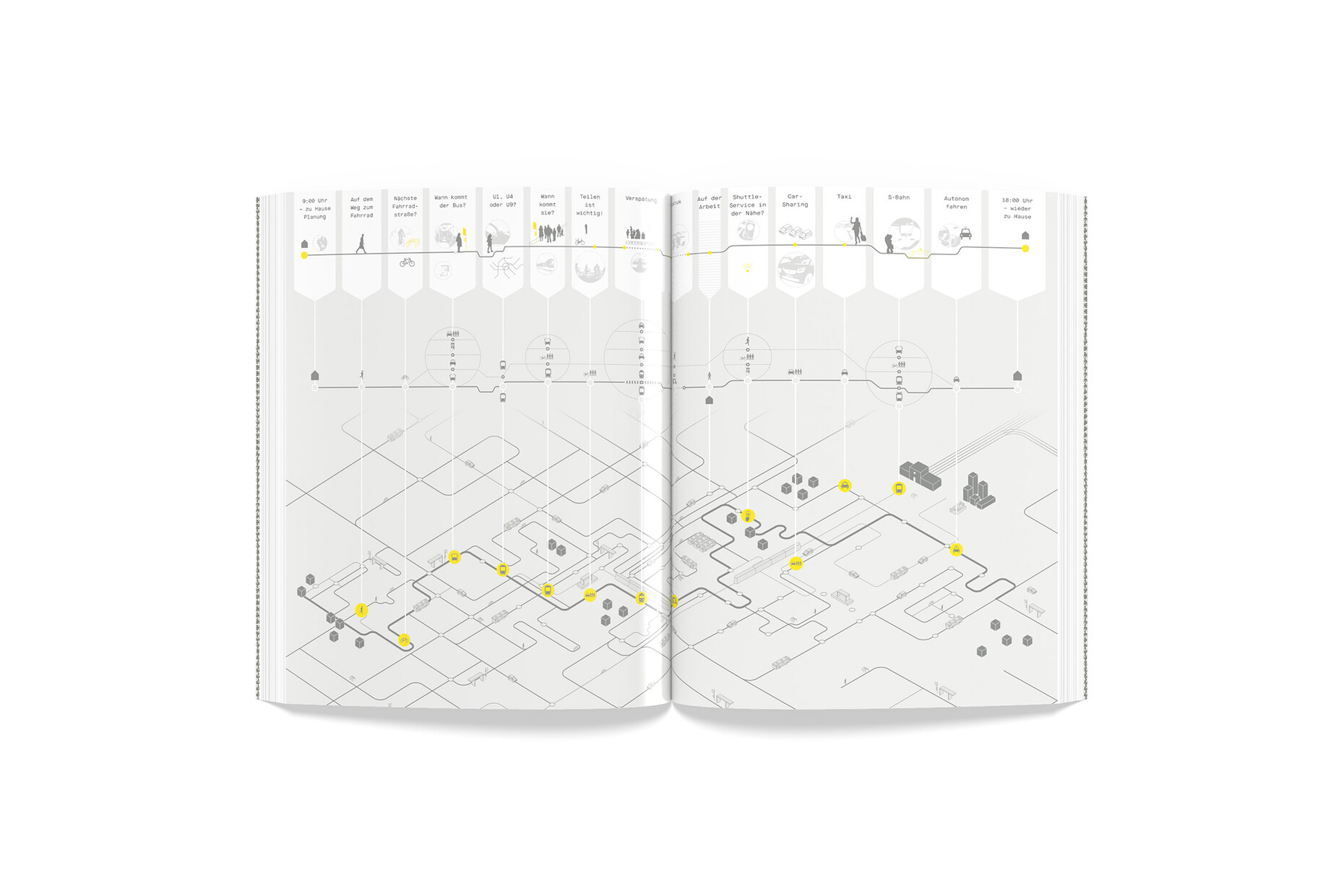

Peter Eckart, Professor of Product Design and Integrative Design and Dr. Kai Vöckler, Professor of Urban Design have collaborated to establish the Mobility Design research program at the Offenbach University of Art and Design. This involves developing concepts in which design approaches are placed in an overall interdisciplinary context with fields such as transportation planning, mobility research in the social sciences, cognitive psychology, architecture, and computer science – with the intention being to promote forward-looking and sustainable projects in the mobility sector. Since 2014, this has included numerous research projects that among other things address the design of a new, networked and multimodal form of mobility.

Alexander Russ: In your research at the Offenbach University of Art and Design on the topic of "Environmentally Friendly Mobility Offerings," the focus is on the role of design and the opportunities it offers. What can design contribute in this regard?

Kai Vöckler: Creating mobility services is an interdisciplinary topic. There are regulatory issues, organizational tasks, and transportation planning. But what is often forgotten in the whole complex is design – in other words, what designers and architects can contribute to mobility options. That is why we have defined the task of mobility design as functioning as an intermediary between a mobility system and the needs of the people that use it – say by providing users with information and aids to orientation or by increasing their sense of safety and well-being. These are primarily design tasks.

Peter Eckart: When it comes to mobility, for many years people in Germany only talked about vehicles and the accompanying infrastructure. However, as you have mentioned we are concerned with environmentally-friendly mobility options such as public transport systems. These services are now very diverse and range from subways, trains, buses and bicycles to various sharing models. All of this has to be understood by users and put into an overall context – and in the end it is design that provides access to these complex systems. One example would be the New York subway’s guidance system that we feature in our book "Mobility Design", and which has now been extended into the urban environment by linking it with pedestrian and cycle traffic flows.

A similar approach is taken by the "regiomove" project that you, Peter Eckart have developed with your office Unit-Design in collaboration with Netzwerkarchitekten. Can you tell us more about it?

Peter Eckart: No matter how large or small they are, public transportation companies in Germany typically operate very autonomously. That means they have their own logo, their own timetable, and are self-contained systems. This can make for considerable confusion when moving back and forth between the individual transport companies. Commissioned by the City of Karlsruhe, the "regiomove" project is intended to show that it is possible to link these autonomous systems, whereby the integration of rural areas plays a particularly important role. The goal is to combine digital and analog information while creating an iconic image that is representative of a unified and coordinated mobility system.

What exactly does it look like?

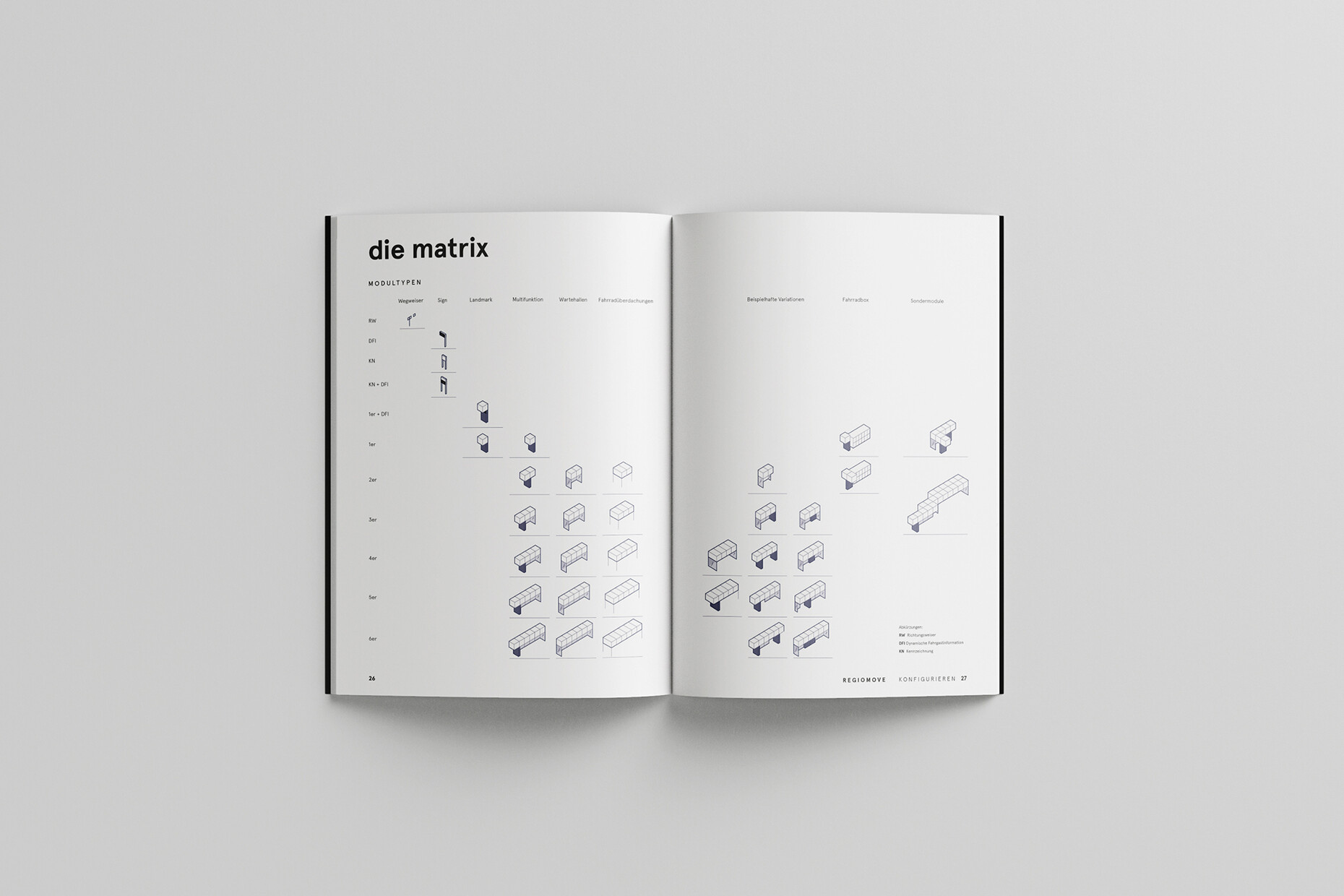

Peter Eckart: There is a so-called "regiomove app" that not only brings together classical forms of local transportation, but also alternative "sharing" products. In addition, there are the "regiomove ports" that we have designed. These are stops that fulfill various functions by not only providing information, but also among other things offer bicycle lockers or repair stations. On top of that they serve as landmarks that give the system a face and can be found in cities such as Baden-Baden, Rastatt, and Karlsruhe or in small communities, too, for that matter.

Kai Vöckler: The digital links make it easier to use and combine different mobility services – all via a single platform! This could lead to the development of a mobility system that works the same way everywhere in Germany – regardless of whether I happen to be in Berlin, Munich or the countryside. In this respect, "regiomove" is a pioneering project.

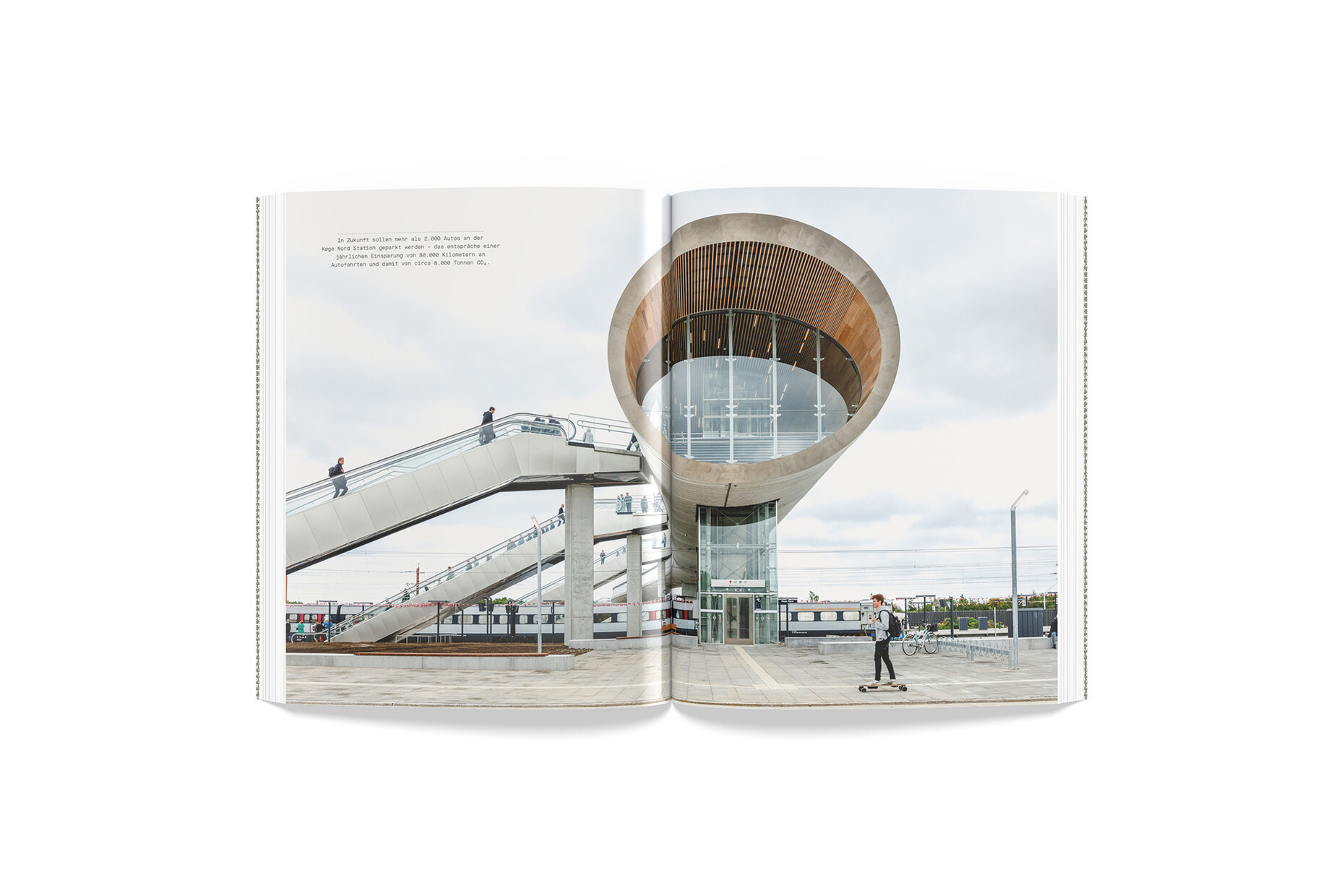

One research project in which you are involved, and which was initiated by the Federal Railway Authority, is the "Train Station of the Future". There you are again working on linking means of transport, but also on increasing the appeal of train stations so that they become places people enjoy spending time in.

Peter Eckart: In the past, Deutsche Bahn failed to recognize that train stations could be places where alternative mobility takes place. That's why many stations were sold. Only now is the company slowly realizing the potential these places have – especially in rural areas.

Kai Vöckler: The privatization of the railways also resulted in attempts to turn stations into shopping malls in the 1990s, such as the station in Leipzig. In the meantime, there is an awareness of what has been lost as a result. This is why the "Train Station of the Future" research project seeks to create a catalog of measures to convert all German railway stations into multimodal mobility platforms. It is therefore a question of grasping stations as places that function as hubs with which different means of transport can be linked together. Our role in the project is to facilitate the aforementioned user accessibility to these places and systems and to develop design specifications that ensure time spent in them is of a high quality and they are consequently well-received.

In France, railway stations are often built on the periphery of cities to serve as multimodal mobility platforms for a specific region. A contrasting example is a project like "Stuttgart 21", where a station located in the city center is being made fit for the future at great expense. How do you evaluate these two approaches?

Peter Eckart: There are good reasons for placing stations on the periphery – especially if you want to design mobility in such a way that there will hardly be any air traffic within Europe in the future. In other words, these stations will become places where it is possible to travel long distances comfortably. And that is something that can be implemented more easily and quickly on the periphery than in the city center. However, in terms of local and regional mobility, which are so important, investments must continue to be made in attractive downtown connections and in supra-regional mobility offerings.

Researchers at the University of Art and Design in Offenbach are also examining various modes of transport that can be considered for environmentally friendly mobility. Cable cars also play a role. Can you tell us more about this?

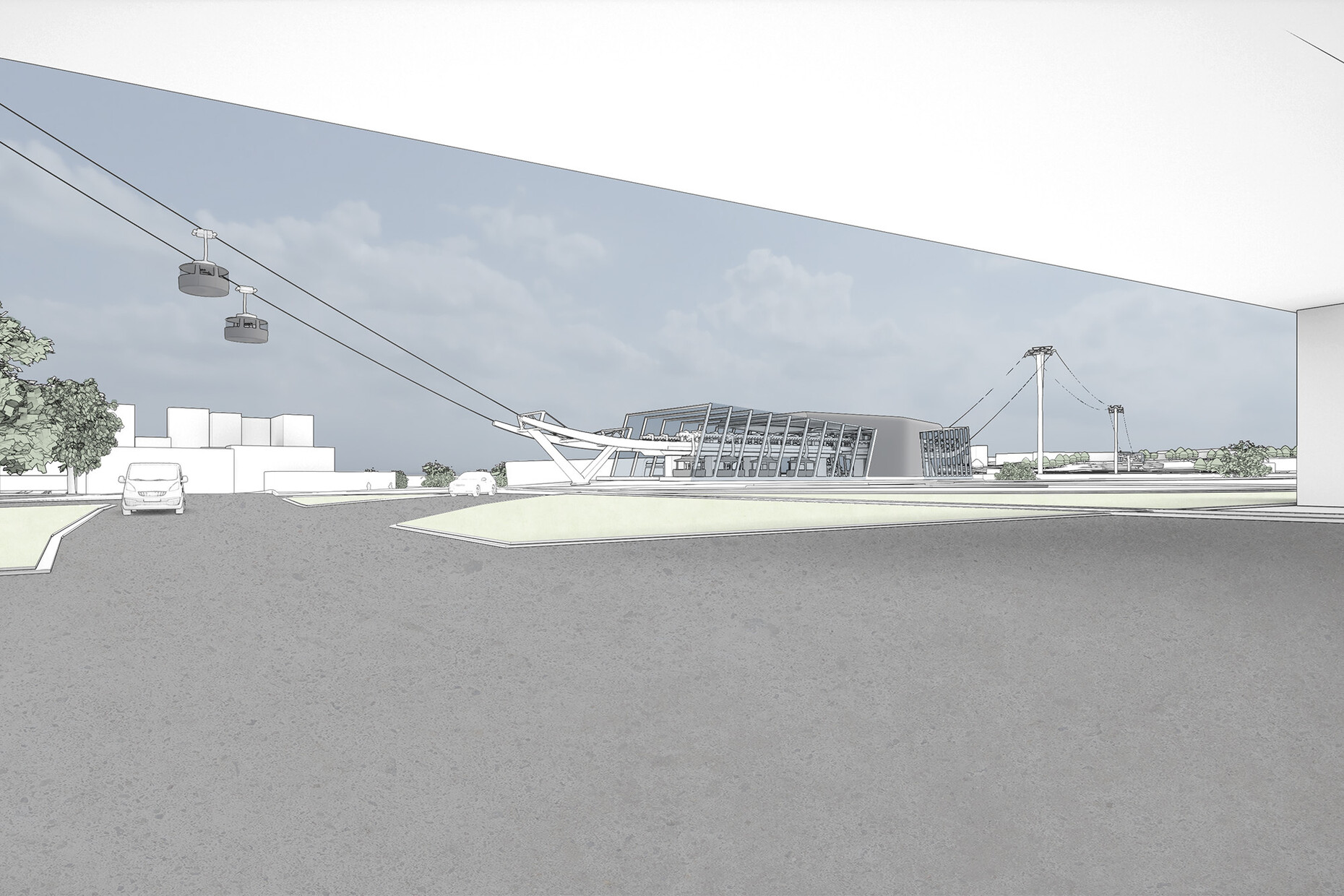

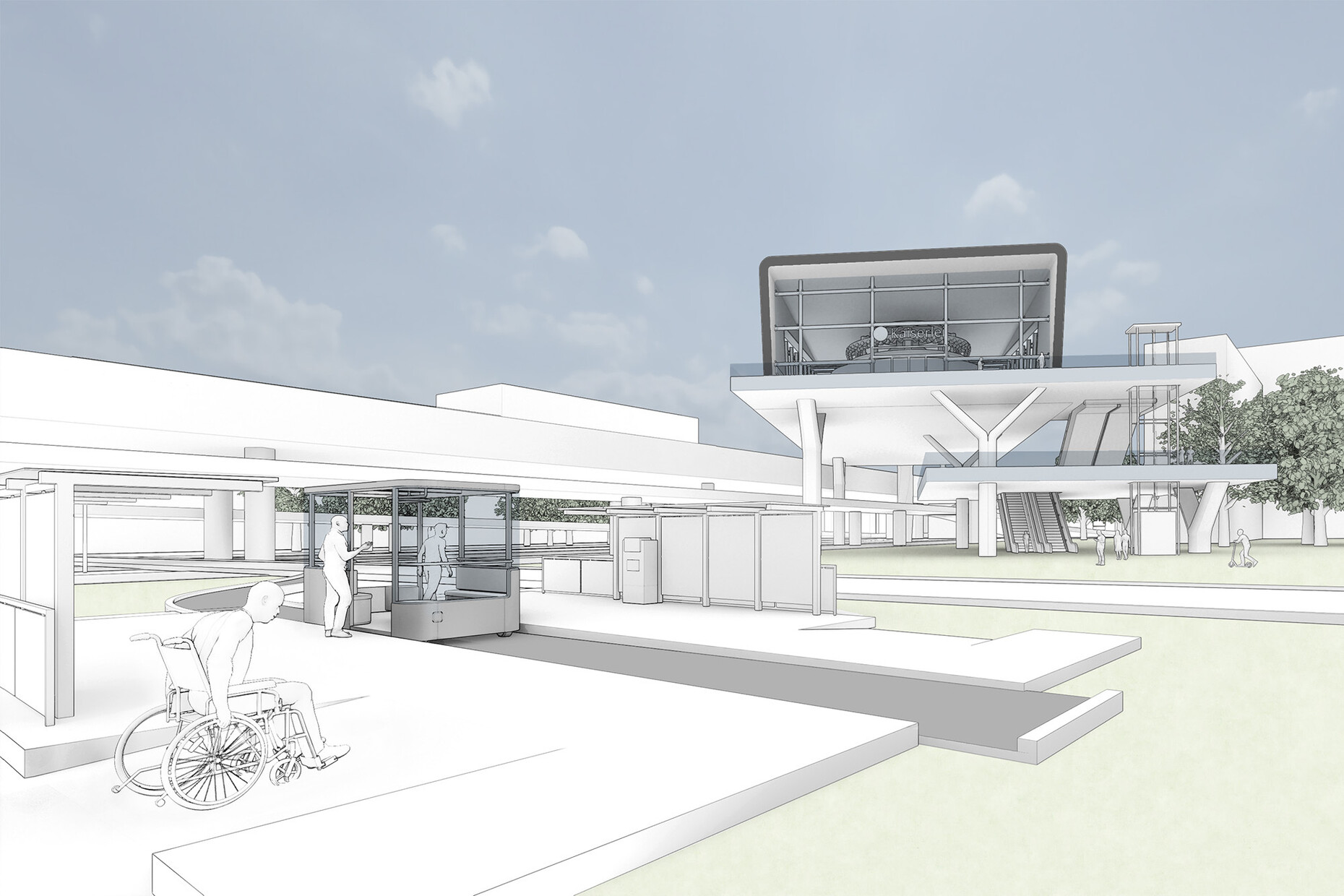

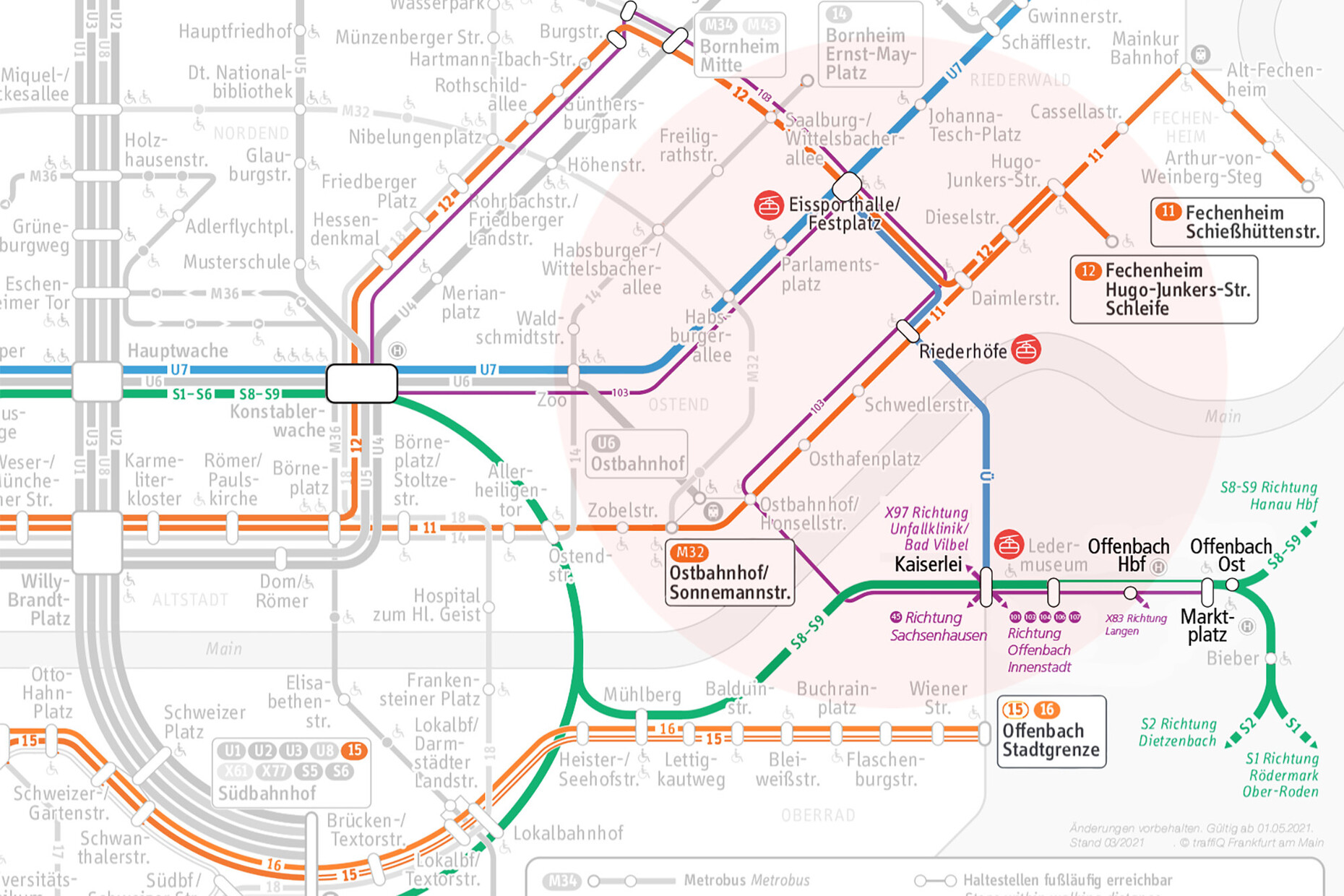

Peter Eckart: To this end we collaborated with Professor Follmann at Darmstadt University of Applied Sciences. He is both a civil engineer and a transport planner and among other things, is exploring the extent to which cable cars can be integrated into a public transport network. That said, here, too, it is apparent that so far there have been mainly functional approaches. That’s why we worked with our students on the task of designing a cable car connection between Offenbach and Frankfurt/Main. In doing so, we wanted to show how design can be used to portray future mobility scenarios. We also wanted to create images that were as close to reality as possible, which would trigger a political debate on the implementation of a cable car in the Frankfurt and Offenbach local transport network – and this is now actually taking place.

Why a cable car in particular?

Peter Eckart: Cable cars can overcome obstacles in urban spaces relatively easily because they simply pass overhead. What’s more, compared to other means of transport the construction effort required to build them is comparatively low. In addition, the respective stations help enhance the value and attractiveness of neighborhoods.

You are also researching the topic of bicycle mobility at the Offenbach University of Art and Design. What requirements must the bicycle of the future fulfil?

Peter Eckart: That is a very interesting question. A quick answer is: The bicycle of the future is not a leisure product, but an important component of our mobility. There is a statement about this by Steve Jobs, who as regards the future of Apple once said that the bicycle converts energy perfectly into movement like no other means of transport. That is why it is so important for the mobility transition, especially in the area of local mobility. As far as the design itself is concerned the bicycle of the future will be influenced above all by the mobility needs in the city and in the countryside. Additionally, you will have the options offered by e-mobility which will allow people to cover distances more easily. There will also be vehicle assistance systems that, say, ensure greater safety when using the bicycle.

Kai Vöckler: At the same time, one of the great advantages of the bicycle is that like the automobile, it holds the promise of free and individual mobility. It also makes for a suitable status symbol. And if the appropriate infrastructure is available in the form of safe and comfortable cycle paths, then bikes will also be used as a means of transport. This is proven by experiences in Copenhagen and Portland, where the use of bicycles increased significantly after the appropriate infrastructure was created.

One specific project is the "Convercycle Bike" that one of your students, David Maurer, developed as part of a term project. The bike is now in production. What is the concept behind it?

Peter Eckart: This is a very good example of the development I just described. The design is a kind of hybrid between a cargo bike and a normal bike. You can choose between a compact mode and a cargo mode, whereby the "Convercycle Bike" can be used like a conventional bicycle in the former. In cargo mode, a 40 × 60 centimeter cargo area is available. This allows the bike to be perfectly adapted to the respective mobility needs.

Why has the successful design of mobility played such a minor role in society so far?

Peter Eckart: In the past, mobility was socially expressed in the design of train stations, whereas now the theme is mainly found in car design. However, you do still find instances of environmentally friendly mobility services being appreciated, such as in the Netherlands. This then also results in successful design. One example is the central station in Amsterdam, redesigned by Benthem Crouwel Architects, Merk X and Tak Architecten and which we also present in our book.

Kai Vöckler: Transport planners and transport operators usually view mobility as a purely functional problem. This often leads to design playing at best a secondary role in this context. However, let me give you a positive example that disproves this: Given its curved shape the "Bicycle Snake Bridge" in Copenhagen designed by Dissing+Weitling, is anything but efficient. However, it offers users a great mobility experience because they can get to know the city in a new way. At the same time, the bridge has become an icon that stands for environmentally friendly mobility. This creates a corresponding acceptance among users, which is needed to design sustainable mobility that is fit for the future.

Book tip:

Mobility Design – Volume 1: Practice

Kai Vöckler & Peter Eckart

Softcover, 304 pages, in English

Jovis, 2021

ISBN: 978-3-86859-646-5

42 Euro