Fresh patina

One could take the small room for a planning error. Or, as they would say in the Ruhr region: Kokolores! – in other words, nonsense. The space in question is the small antechamber of the new reception building designed by Max Dudler for Eisenbahnmuseum Bochum. The empty room is extremely narrow – both in terms of depth and width. Sixteen-meter-high walls amplify a feeling of constriction, something only undermined by the fact that the room does not have a ceiling and instead opens up to the view of the sky above. That said, it’s not just the unconventional proportions which make the room special: the moss covering the benches next to the exposed concrete walls and growing slowly upwards has a quite astonishing effect. The velvety green imbues the austere architectural space with a big portion of nonchalance – which may well be just the ticket in a down-to-earth environment like a railway museum.

The railway museum in Bochum’s Dahlhausen district is one of the biggest in Germany and an important part of the “Industrial Heritage Trail”. In the former train depot, and it boast over 46,000 square meters, more than 120 historical railway vehicles of all kinds have been put on display. The museum train leaves for the Ruhr valley at regular intervals. Hitherto, the museum was housed exclusively in historical railway buildings, such as a roundhouse with a turntable and a water tower. What was missing was an adequate reception space for the visitors – a building for exhibitions, events, the museum shop and supply facilities.

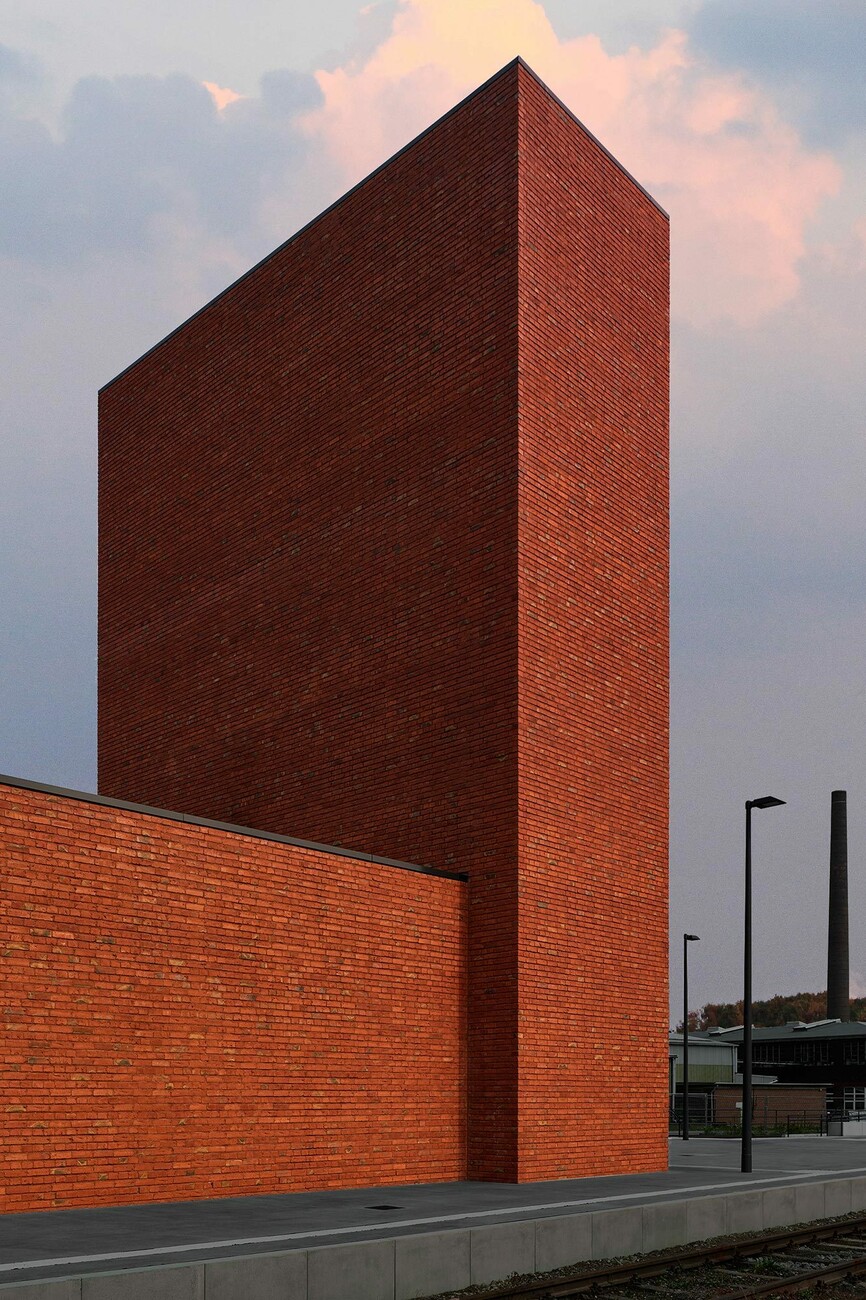

Dudler’s design now complements the older structures. The brick building harmoniously meld with the ensemble of architectures belonging to the former rail yard. The new design truly breathes the architecture of railroad buildings. A striking tower marks the entrance and makes the museum visible from afar. At the same time the building’s volumes reference the typologies of railway construction – from the train station with a clock tower to switch towers and engine sheds to water towers used to fill the thirsty steam locomotives. The fine irregularity of the red brick façade created by the slight variations in color in the hand-fired bricks is captivating to look at.

Viewers enter the new museum building through said antechamber and are greeted at first by the reception area and museum shop. The elongated exhibition space stretches out behind these. Broad window areas provide views of the track system. A small lecture and workshop hall is connected to the exhibition space. The interior rooms are well-nigh desaturated in terms of color: The interplay of the grey exposed concrete, the grey screed, the black metal installation shafts on the ceiling and the oak wood of the furniture makes for a simple, almost severe elegance. Clean and precise details further emphasize the sophisticated look. The new building is functional and impactful architecture through and through – in fitting with its use and well suited to the location. Well, not entirely functional. Which brings us back to the small antechamber.

Max Dudler architects had won the competition tendered by the City of Bochum with a design that while already including the same cubature nevertheless envisaged further uses for it: The roof surface was to offer space for a terrace and the tower was to be used as a viewing platform. It would certainly have been a plus for visitors to be able to get an overview of the expansive compound of the railway museum. Yet the limited budget foiled the execution of this idea. What remains is only the tower as a landmark: and the empty space inside it, which should have housed the staircase to the platform. Now the growing moss cover is lending it the same type of patina that rust gives the old steam locomotives exhibited in the museum. Both have a certain romantic sense of the obsolete. Which makes the tower with its particular interior the most multi-facetted addition to the museum: It combines transience and robust constancy.