Transforming Patterns

Anna Moldenhauer: What exactly is the Hightech Agenda Bavaria?

Prof. Markus Frenzl: It’s a technology offensive and a funding initiative with which Bavaria is investing approx. 5.5 billion euros in technology, AI, university innovations, and transformation. The Munich University of Applied Sciences Faculty of Design submitted four applications for research professorships and all of them were approved, which really surprised us. This helps us a lot with regard to advancing design teaching in the context of transformation topics and, above all, expanding design research!

As part of your research professorship you will research the socio-cultural aspects of transformation and innovation processes as well as design as cultural production. What do you actually mean by this?

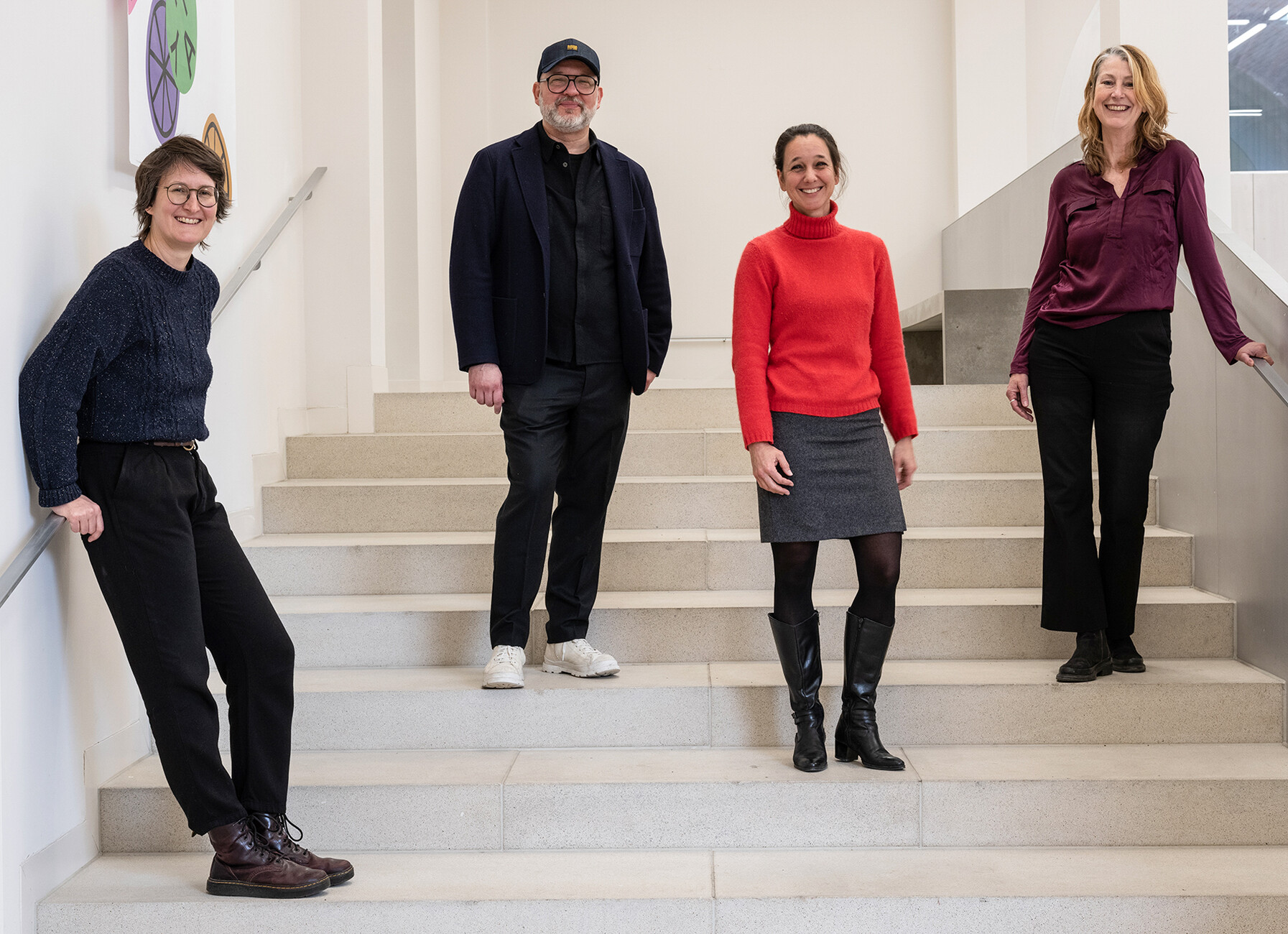

Prof. Markus Frenzl: Thanks to additional funding for design research from the Bavarian state parliament, in the context of my Hightech Agenda professorship I will now be able to establish an institute for applied design research. My focus is on design cultures and innovation cultures. I will be joined by my colleague Professor Eileen Mandir, who was appointed to the newly created professorship for Systemic Design as part of the Hightech Agenda. She studied Technical Cybernetics and has worked in the field of mobility research. As someone who first worked in other areas, she brings a completely new perspective to the field. Two research assistants, Katrin Laville and Dr Silke Konsorski-Lang, will also be part of the core team.

At our institute, the main focus as regards transformation issues will be on the role that design plays in the development of new cultural patterns. Wilhelm Vossenkuhl once said that “cultures are ways of making a world”. This is fascinating, as by ‘cultures’ we naturally mean a more comprehensive cultural change through design and not highbrow culture because specifically in Germany we do not tend to treat design as part of ’culture’.

True, unfortunately it's often seen as “style”, which doesn't even begin to do justice to the diversity of the subject of design.

Prof. Markus Frenzl: In Germany, funding and support for design is always the responsibility of ministries of economic affairs, which is not the case in many other countries. I believe that many members of the public as well as politicians are hardly aware of design’s function fostering culture and identity. This value gets ignored if the only interest is in potential financial gain. Unfortunately, one of the great missed opportunities in Germany was the failure to understanding the social relevance of design. After all, with our design history, the Bauhaus and the Ulm College of Design (HfG Ulm) – the two most important design schools of the 20th century – we should actually be a nation that has a tremendous understanding of design as a discipline that informs culture. Instead, design is more of a cultural topic in France, Italy, and Scandinavia. There's a more comprehensive understanding of design there, and people there are proud of their designers and their design history. In Germany, few people today actually realize that HfG Ulm was intended to constitute a new democratic beginning after the end of World War II, that its objective was to use design to contribute to democracy and a new society. Democracy is currently under threat again, but is someone today about to set up a design school for that reason? Hardly very likely.

A few years ago, I spent a research semester addressing the topic of “The Public Reception of Design” and came to the conclusion that 1980s design and the critique of functionalism had a very strong influence on the perception of design in Germany, and that these ideas still have an effect. In this context, I had a long conversation with architect and designer Volker Albus, one of the most important protagonists of neues deutsches Design (New German Design). It gave me a much better understanding of how important subjectivity was to designers in the 1980s as a means of counteracting functionalism. They wanted to represent the world as they experienced it and relied on deliberately different, provocative, and sometimes strident designs and thus reinject subjectivity and emotionality into design. However, I don’t think the public really took note of the critique of functionalism that subjective design entailed, and instead the designs were often merely perceived as bizarre or provocative. Instead of recognizing design’s relevance to society, it is still often misunderstood today as a gimmick, a means of aestheticization or driving sales. And the media reinforces this view, as rarely does it reflect on design in cultural terms. Interestingly, other elements of popular culture such as music are often discussed in the arts pages. In the case of design, however, this either doesn't happen at all or only with a very distanced, often derisory spin. I find that very sad.

The discipline is sometimes reduced to superficial product design for a wealthy clientele– even though every object we live with is a product of design. How do you wish to use the institute to communicate the great importance design has our society?

Prof. Markus Frenzl: The “cultural patterns” in the context of entrepreneurship, transformation, society, digitization and innovation are a core topic. What are existing cultural patterns? Where is there potential to transform them and how can new cultural patterns be created or initiated while taking history into account? Design is very much in the Modernist lineage, which sought fundamentally to brush what existed aside, redesign everything, and in the process develop society anew. Every design has a historical context. If people are merely confronted with a radical transformation without being shown how it links to something familiar, they will probably reject it – the history of Modernism has shown us this, too.

Self-restriction is considered a threat.

Prof. Markus Frenzl: Yes. And at this point specifically against the backdrop of globalisation and digitization it's important to make it clear that we can rely on much that has already proven its worth. You could also ask: “What is beautiful, tried-and-true, and worth preserving? Let's choose this cultural pattern and see how we can transform it and make it viable for the future!” This is the meta-level informing our work at the institute – exploring existing cultural patterns in order to develop them into new cultural patterns. As regards teaching, we want to bring together design, design futuring, design theory, and entrepreneurship. Applied design research is to be given a firm basis at MUAS in the form of the institute, but we also want to ensure that it gains greater relevance in Bavaria as a whole. As part of last year's munich creative business week (mcbw), for example, those of us at the Faculty of Design, together with the other Bavarian design faculties, proved how much design research is already taking place in Bavaria, even if this diversity has not yet been communicated as coming under the overarching umbrella of design research.

What's currently on offer?

Prof. Markus Frenzl: There are five distinct Bavarian design faculties with a wide range of focal areas and fields of specialization and research, and there are also several individual research institutes. Normally, within a federal state, design schools tend to compete with one another. The networking of Bavarian design faculties was therefore an enormously important step for us, which gives us more self-confidence and clout, particularly if one considers the large, combined number of students and lecturers. It was also interesting to be able to internally compare what research means at other colleges and faculties. A distinction is generally made between research for design, research on design, research through design, and research by design. As a faculty at a university of applied sciences, our focus is primarily on research through design. With this in mind, and on behalf of dci, we’ve consciously chosen the term “applied design research”. We also recently renamed our MUAS Master's program, of which I am the program director, to emphasize our focus on applied design research.

Design research doesn't mean the devising academic theories that are far removed from practice. We're also interested in showing that design is a cultural driver of transformation issues, and that it can be meaningful. It's also important to communicate this to the business world, and in this context, there's a quote from design theorist, lecturer and designer Gui Bonsiepe from 1994 that I particularly like: “While the work of the scholar is aimed at cognitive innovation and the work of the engineer at operational innovation, the work of the designer is centered on socio-cultural innovation. Design integrates the strange and alienating aspects of technology into an everyday social situation by means of the social institution known as the corporation.” Socio-cultural innovation – I think that's great! It's about innovation in culture, the corporate world, and society. And that's what's really at the heart of design work.

People are the focus of design.

Prof. Markus Frenzl: The benefits to society of design research are still not sufficiently recognized, and our profession often has to justify its existence. Are you even real academics? Are you real engineers? And my answer is no, we are real designers! We have our own way of doing research, and it's not worse or better, it's simply different. That's the way it is in every discipline. Applied design research is primarily research through design. In our design discipline, knowledge is generated through the process of research, experimentation, and prototyping. This can involve many more iterations, constantly abandoning things and starting again. This is not the case in other disciplines, where the concept of research is more focused on exploring irrefutable findings. Claudia Mareis, Professor of Design and the History of Knowledge in the Dept. of Cultural History and Theory at Humboldt Universität zu Berlin, describes design as an independent knowledge culture, as an epistemic practice in its own right. In other words, the very act of designing and making something tangible generates knowledge that each time move the discipline a further step forward.

What's the objective of the new institute?

Prof. Markus Frenzl: To summarize our mission statement: “The design cultures institute for applied design research (dci) sees design as an identity and culture-forming practice with its own culture of knowledge and research. Through design, it researches cultures of perception, knowledge, action, innovation, as well as corporate culture. It identifies familiar cultural patterns, adapts them, and advances them in order to make them culturally compatible and to provide impulses for social, ecological, technological, and entrepreneurial futures."

Our methodological fields lie in culture and design studies, cultural anthropology, and design futuring. Our formats are primarily participative formats, interventions, and speculative projects, but we also use education and transfer formats such as symposia, workshops, exhibitions, and experiments. It's also about creatively dealing with the conflicting goals of the different logics of the systems that give rise to culture, namely politics, law, business, democracy, scholarship, and civil society. This may also stimulate entrepreneurship. The following are the general subject areas we've defined for the dci so far: Urbanity and Mobility, Digitalism and Digital Cultures, Crafts Skills and Craft Cultures, Health and Wellbeing, and finally, Transformation and Participation.

Each one is a very large subject area.

Prof. Markus Frenzl: These are indeed huge subject areas, and you could set up a separate institute for each of them in order to specialize. Our aim at the dci, however, is to identify cultural patterns in different fields and to benefit from different content-related perspectives in order to advance them. This is the specific expertise we have at our institute, in the faculty and at the university as a whole. Thanks to our network, we're also able to realize joint projects, for example in cooperation with the Strascheg Center for Entrepreneurship (SCE), the internationally renowned entrepreneurship center here at MUAS. We supervise dissertations in the field of digital ethics or on the topic of car-free neighborhoods. For HM:UniverCity, the MUAS’s innovation network, which is very active in the field of co-creation, participation and urbanity topics, we've contributed to research supporting the topic of urbanity and participation for the New European Bauhaus project “Creating NEBourhoods Together”. Current research proposals include topics such as “AI in X-ray diagnostics” and “Participation in the context of democracy”.

Are there other research topics as well?

Prof. Markus Frenzl: In terms of content, I think it would be an exciting challenge to explore new cultural patterns for the furniture industry. Many manufacturers are now looking at sustainability, circular products, and recyclable materials, but the standard business model is still mostly based on producing larger quantities and offering ever more products. The environmental problems associated with this are still simply being transferred to the next generation. Many years ago, BMW developed the principle of “not selling cars, but mobility” instead. And of course, BMW still sells cars, but they've formulated a view of the future that shifts the focus from their products to an overall perspective and asks the question of what is actually at stake concerning their use. Along these lines, furniture manufacturers would have to say: “We don't sell chairs, we sell home living, and the culture that goes with it.” This gives rise to some interesting research questions: What could ‘sufficiency’ really mean for manufacturers in this context? What could new cultural patterns for furniture companies look like under this premise? How could companies continue to be profitable?

Another particularly exciting topic for me is researching the potential of Bavarian artisanal cultures that still exist. I think it’s wrong that in Germany we don't support traditional artisanal skills if they are no longer economically viable. In Japan, for example, this knowledge is protected as a “national treasure” and outstanding Artisans receive funding as "living national treasures" in order to keep centuries-old artisanal cultures, material and processing expertise alive for future generations.

It's valued as part of the culture.

Prof. Markus Frenzl: Exactly. When an artisanal skill disappears in this country, it always means that we lose knowledge and may have to start all over again at a later date. A good example is the durable concrete used in ancient Rome 2,000 years ago, which compacted when exposed to moisture, whereas the steel rebar in modern concrete rusts when exposed to moisture. The knowledge about this material existed long ago but was then lost, and as a result scientists first had to rediscover the idea that burnt lime and pozzolana give ancient concrete this property. Who decided a few hundred years ago that this knowledge was no longer needed?

Specifically with regard to sustainability, there are material and processing skills that we shouldn't lose, even if their value is not yet clear to us. For example, can elements from the traditional production of fences be transferred to a new context, for instance for the sustainable cladding of walls? Could skills from glass painting perhaps play a role in liquid crystal and solar technology, or in the digital world? We don't yet know what skills from yesterday we will end up needing tomorrow. Ultimately, this is also Modernity’s dilemma: In a discipline that invents and shapes the future, we nonetheless find it difficult to establish a link to the past. Since digitization, however, design has also taken on the new role of preserving the culture of material objects. We want to transfer existing cultural patterns into new areas where they can be of benefit. Because this transfer is a particular strength designers have.

What else are you currently involved in?

Prof. Markus Frenzl: With participation, co-creation and future skills with regard to the context of mobility, i.e. what skills need to be promoted among people so that they are willing to change their mobility behavior, and what formats should be developed for this? There was a recent project in Munich as part of the MCube cluster on the topic of car-free neighborhoods, where alternative uses for parking spaces were tested on a few streets for several weeks. This project led to heated discussions locally: Many people were skeptical whether the campaigns were really temporary and felt that politicians were instead trying to impose something on them. In response to the term “real laboratory”, which is a common term in the research context, residents replied that they didn't want to be treated like lab rats. This shows us that experimentation, a natural tool for the design industry, is not always welcome in society and that our culture is not intrinsically open to experimentation. And this is especially true when it comes to mobility or cars. The temporary introduction of the 9-Euro ticket offering nationwide rail travel, by contrast, was a welcome experiment as well as an exception.

You can't think a transformation process through to the end in advance; you have to try it out by experiment. We therefore need to communicate the value of experimentation to society in a new way. In projects, this also includes the communications: For each project, you need to discuss with those involved what individual terms can be found for the desired approach that have positive connotations. After all, a real-world laboratory ideally involves a joint experiment about the future; it's all about participation and co-creation. This only works if everyone takes part as equals.

What do you have planned for the future?

Prof. Markus Frenzl: The research opportunities within the framework of the HTA research professorships are initially provided for five years, but of course we're thinking more long-term with the design cultures institute (dci). Our aim is to give the institute a solid footing and ensure that project findings do not fizzle out at the university level. The dci is about cultural patterns for major transformation issues. Design is the ideal interface for this as a transfer and intermediary discipline in society that offers participatory formats, symposia, documentation and book publications.

Change creates opportunities. As a society, we learnt during the pandemic that our understanding of how things work can disappear overnight and that we need to find a new approach. We learned that change is needed, and that it's urgent. Perhaps this realization will help design work and design research. Our task is to show that this transformation affects everyone and to ensure that it doesn't just take place “from the top down”, but that every person in society contributes to it with the decisions they make.

You've been teaching for many years as a professor of design and media theory, as Vice Dean of the Faculty of Design at the MUAS and as head of the Master's program. How do you reflect students' questions at the institute?

Prof. Markus Frenzl: The students immediately understand what “applied design research” means for the Master's program and that this conveys the focus of the program more clearly. That it involves applications-oriented research rather than research which has little practical relevance and is not contextualized in everyday phenomena. And that it can also involve social movements ranging, for example, from the appropriation of public space to new forms of mobility. It doesn't always have to be about the design of a particular object. Many of the students have high aspirations for their work when it comes to social and sustainability-related aspects. Transformation, changing the status quo, participation and equality are also core design themes for younger generations.

Also concerning a search for meaning?

Prof. Markus Frenzl: Yes, even if in my opinion it's essential to look at history, because the search for meaning didn't just start today. Many movements, such as the quest for greater sustainability and equality, have their roots in previous generations. Of course, the new generation has a desire to do everything differently and not to just build on what happened before, but it's helpful to know what has already happened and what can be built on, as this increases the chances of an idea being socially acceptable. We can't answer a general research question such as “How do we save the world?”, but we can improve a small part of that which exists, which then contributes to a larger change. Many MA theses currently revolve around socially relevant issues, aspects of transformation, new uses, and changes in behavior, and deal with the visuality of gender identities or aspects of identity in the digital world. I think it's great that budding designers are tackling these issues and not just saying “I want to design a cool new type of light".