YOUNG TALENTS

Overcoming boundaries

Can Palermo, Sicily’s capital and the fifth biggest city in Italy, closer to Africa than the Alps and a far cry from the centers of Italian industry, be a good place for designers? It is at any rate the place to which Francesca Gattello and Zeno Franchini chose to relocate in 2016, the city on the very periphery of Europe. Under the name Studio Marginal, they not only run design projects that involve participation, artisanal skills, and research but also teach young designers. “Almost every day someone asks us why we moved to Palermo,” says Zeno Franchini in our video interview. The typical notion is that people only move here if they have relations living here or have been sent by the government or work as a teacher or police officer. Sicilians simply can’t imagine that anyone should actually choose to move here for work – on the contrary, many of them leave Sicily and move further north. But it was precisely the difficult economic and social situation that attracted Studio Marginal: “We wanted to engage with the topic of migration,” explains Franchini. “Not, however in a condescending manner but rather to create a place where it’s possible to exchange ideas with other people.” And as Palermo is often the first port of call for many migrants it seemed to the designers, who both originally hail from Verona, to be just right for their purposes. After stints of working in a number of European countries they had not experienced a sense of belonging or of wanting to work in any of them long term, adds Francesca Gattello.

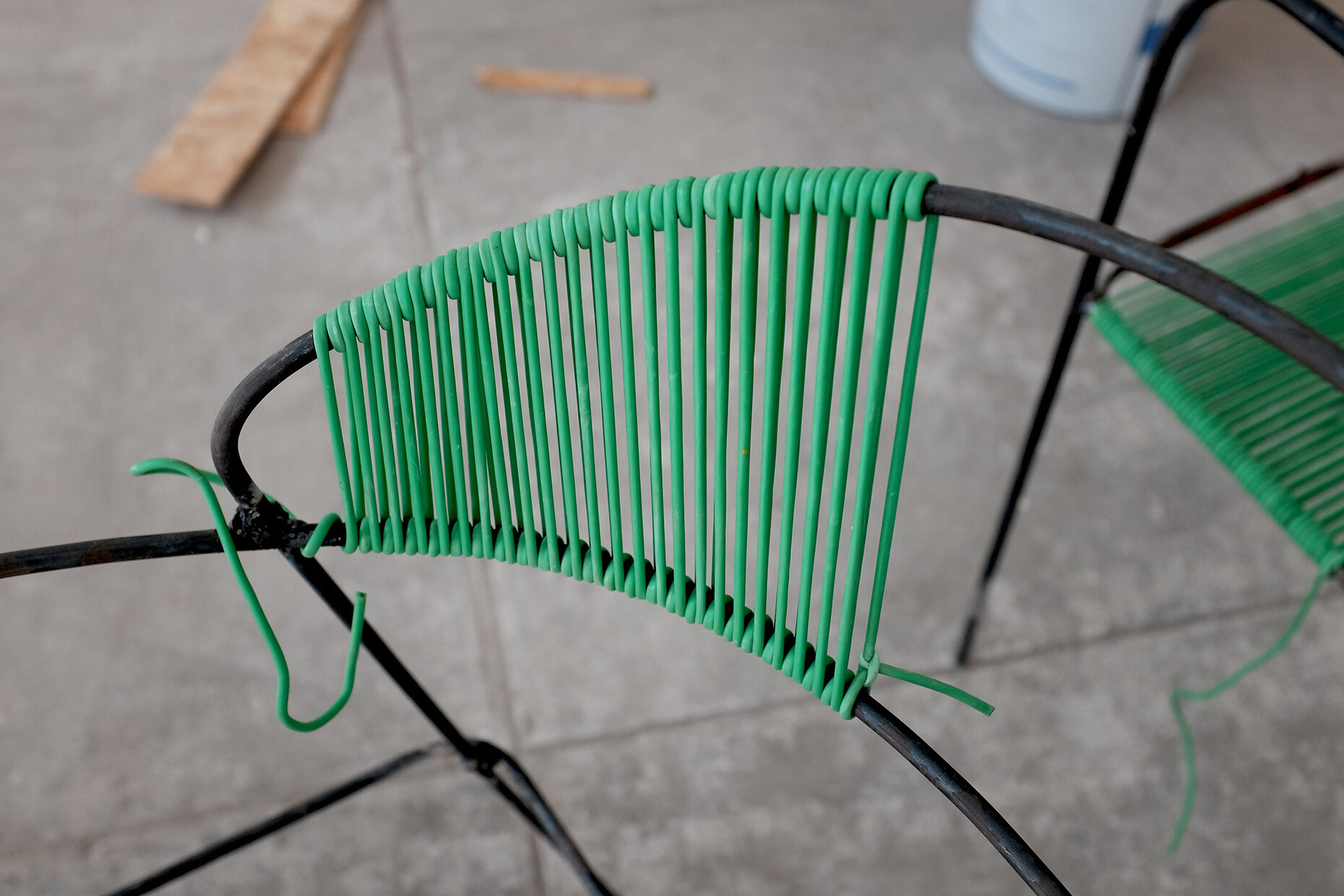

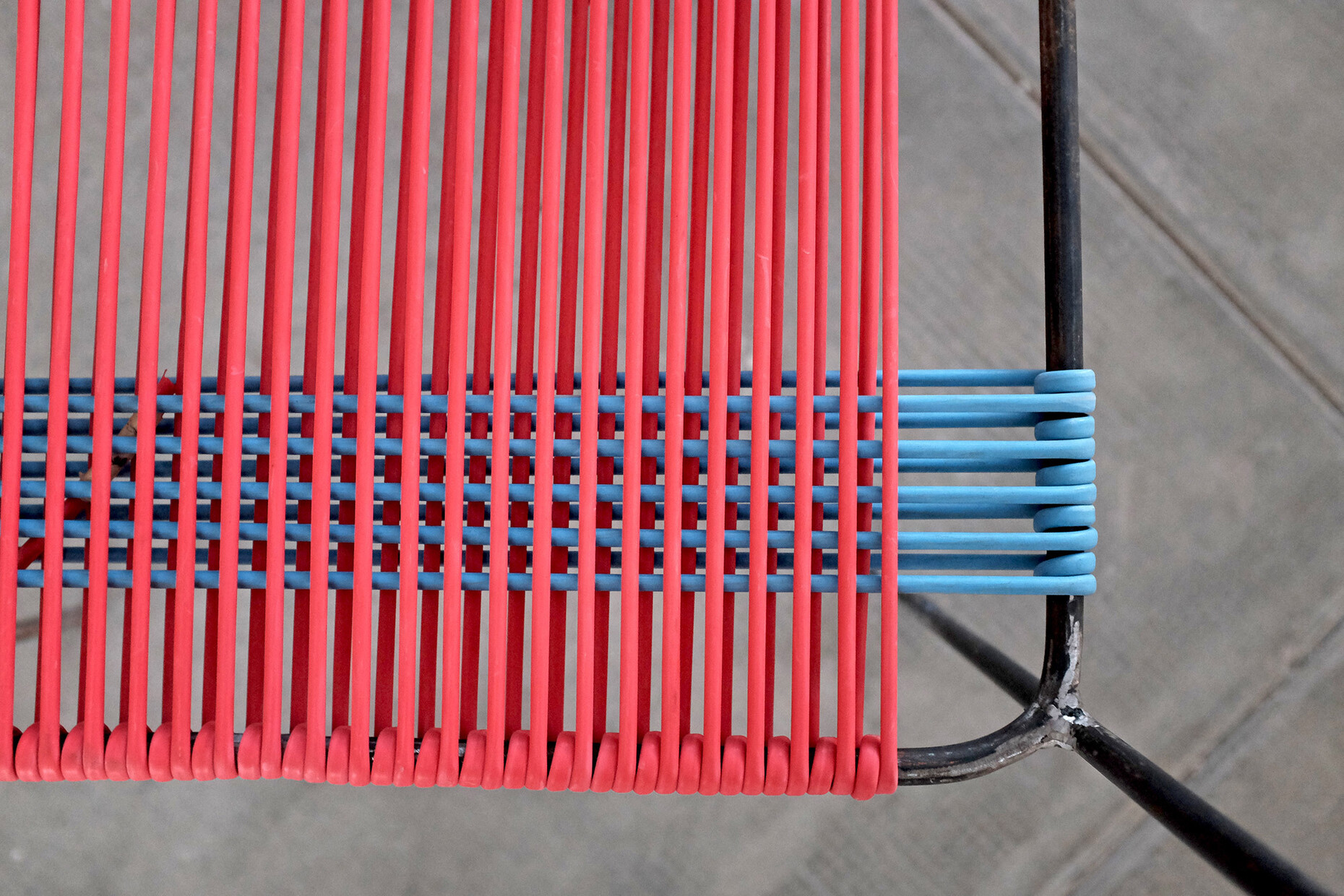

Francesca Gattello and Zeno Franchini got to know each other while studying for their Bachelor degrees at Italy’s most famous design university Milan’s Politecnico. After graduation, Francini moved on to the Eindhoven Design Academy to study Social Design while Gattello stayed in Milan to do her Master’s. They set up Marginal Studio 2015 in Eindhoven. They were are somewhat critical of the curriculum at the Politecnico where they feel students are given a false impression of what it’s like to be a designer and nobody questions the fact that clients will come from industry. “I somehow felt I’d been duped,” says Francesca. And in Eindhoven according to Zeno students learn that they will work either for the state or for museums. It was these experiences that made them all the keener to adopt a different approach to design in their own work, to have a different function for society that is not connected with the customary capitalist system. Today, they collaborate with people from Palermo’s migrant community on projects for the public space, designing and making furnishings and furniture. In other projects the designers discover new shapes and applications for traditional artisanal techniques, such as wood inlay work. They bring together experienced local craftspeople and newcomers from Africa so as to remove cultural barriers. While discussing the right welding technique for a metal frame, prejudices are swiftly forgotten they suggest. “This creates beautiful moments of unanticipated openness,” says Franchini.

When asked to define their role as designers they say they are quite simply people who shape things and can create spaces. However, in practice things are more complicated than that: In order to secure budgets for their projects they have to apply to foundations and social organizations and such applications tend to be very time-consuming. They have even created a kind of NGO themselves so it allows them to officially employ the migrants. After all, as Gattello stresses, people must always be paid for their work. However, that does not leave much for them; indeed, they describe their own situation as precarious. Endowments and teaching appointments, for example at Syracuse University, merely help pay the basics. But their contact with the students also serves to add something to their own work as a studio. Franchini and Gattello see parallels between teaching and their work with the newly-arrived migrants, as both are about material culture. It is obvious that people from Africa can bring their experiences with certain materials or craft techniques to bear. “And we want to find out more about that,” says Franchini. "Find out what connections they have to the local, Sicilian traditions.” They also encourage the students to become engaged with their own material culture. “After all, the most important knowledge that you have as a designer is that about where you come from,” says Zeno Franchini.