Column

Social gas station in the mice bunker

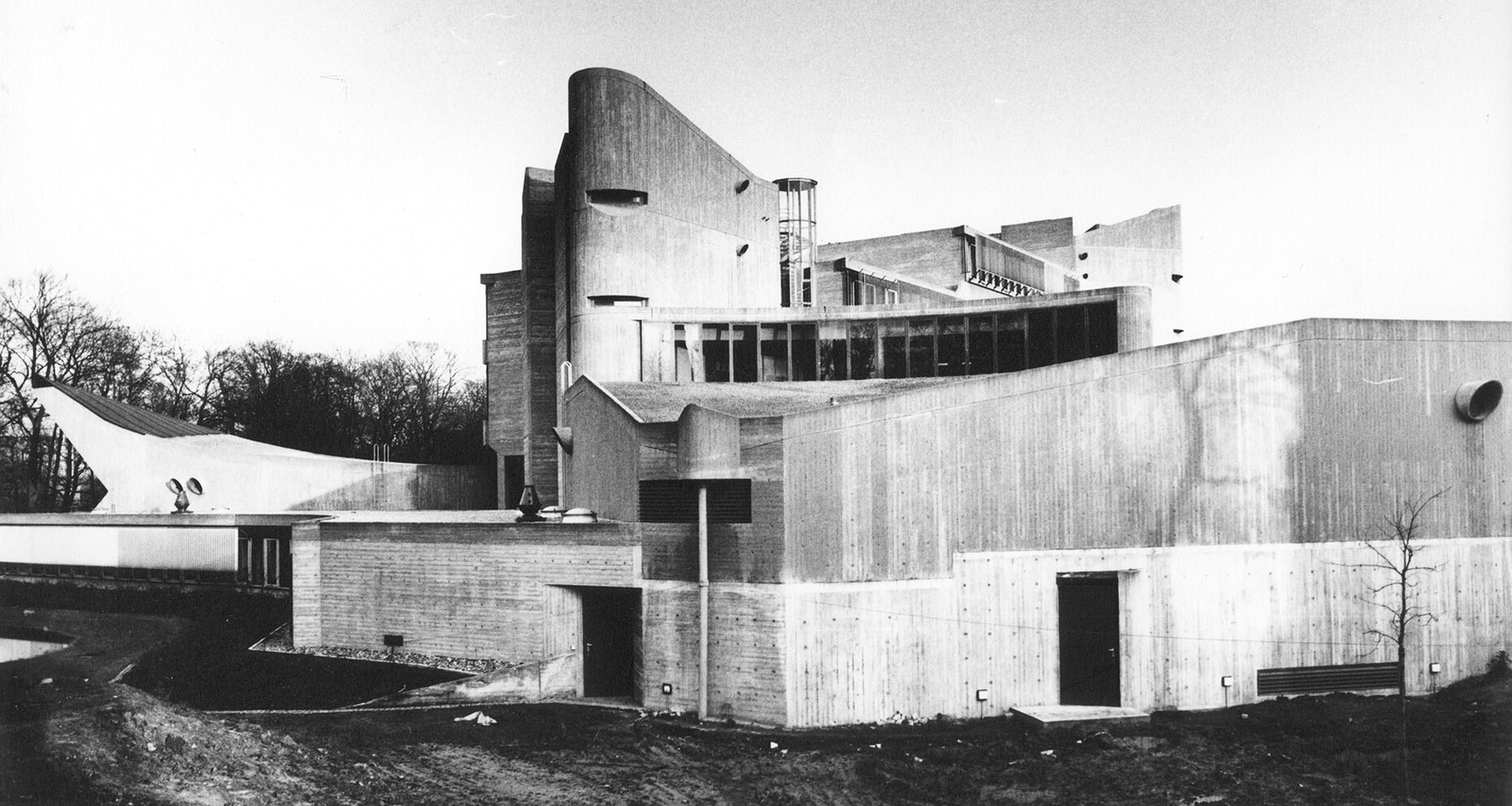

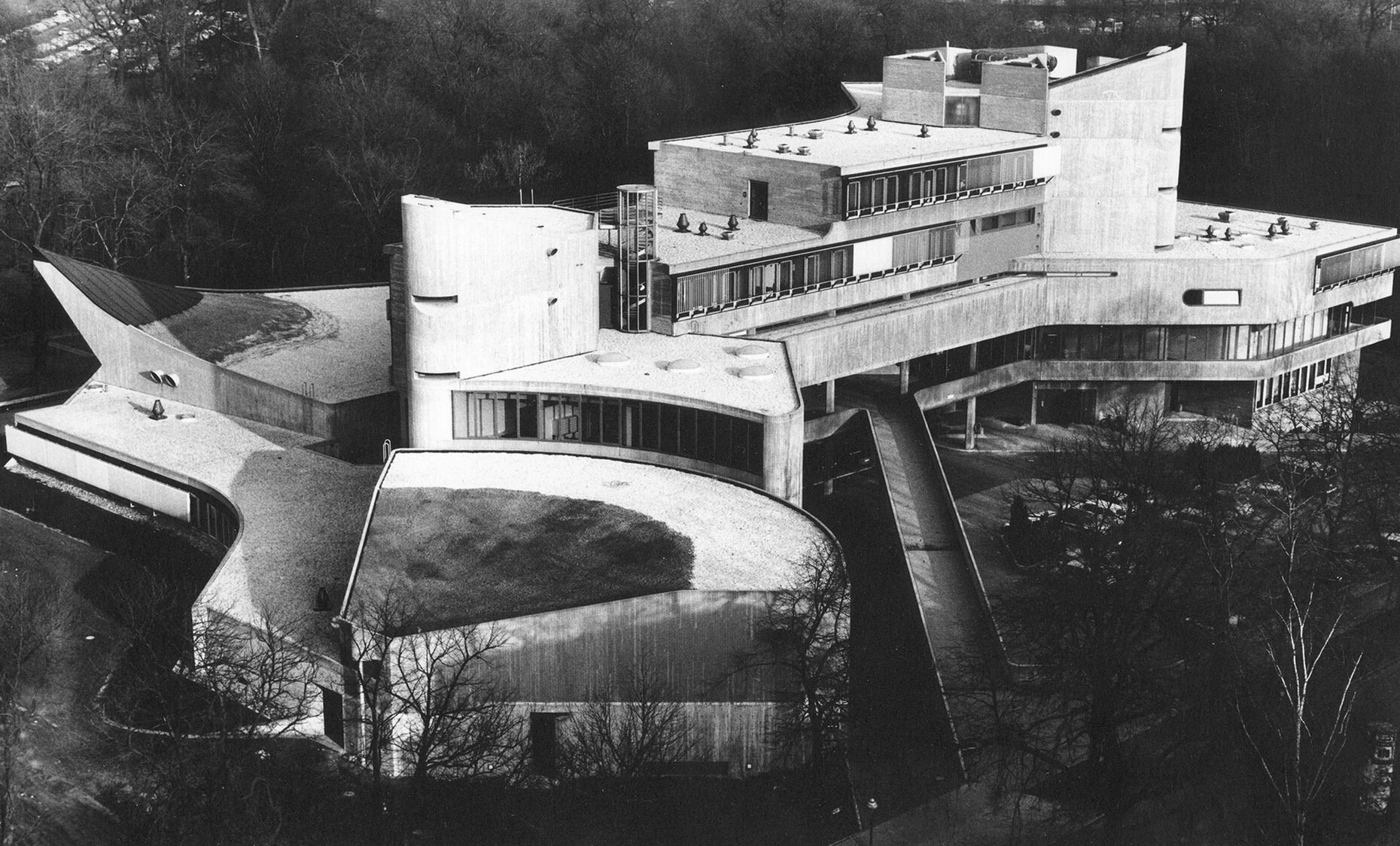

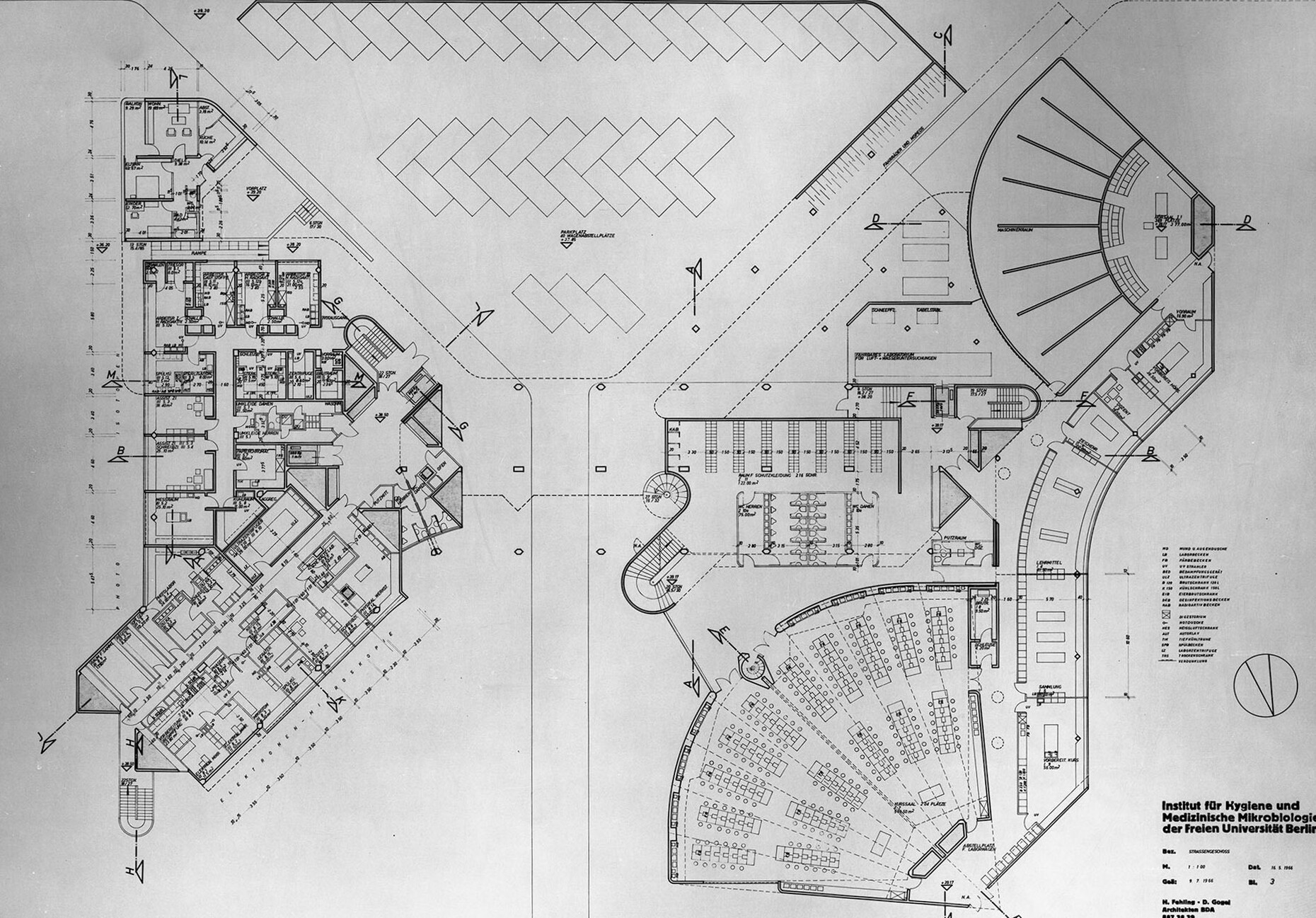

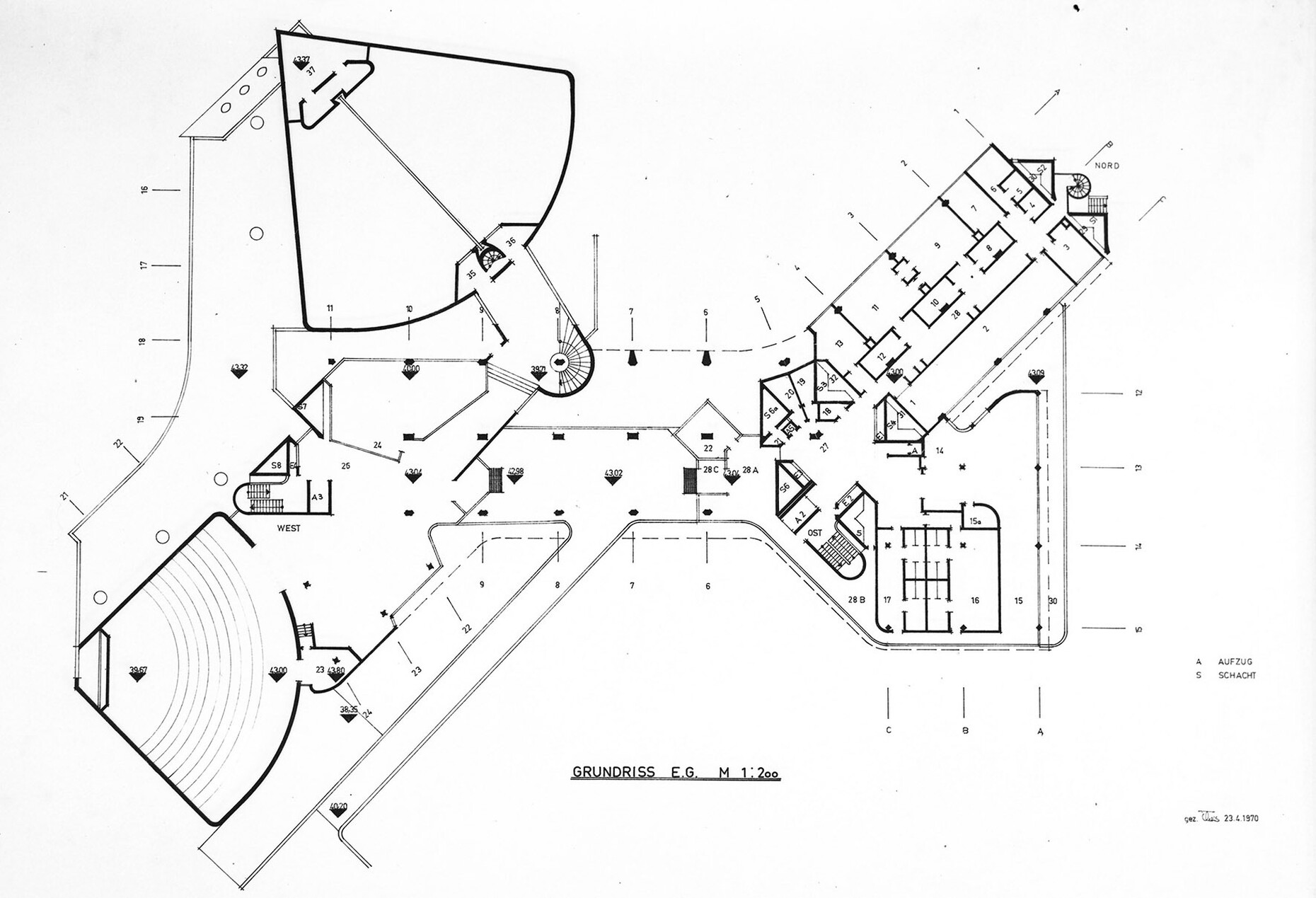

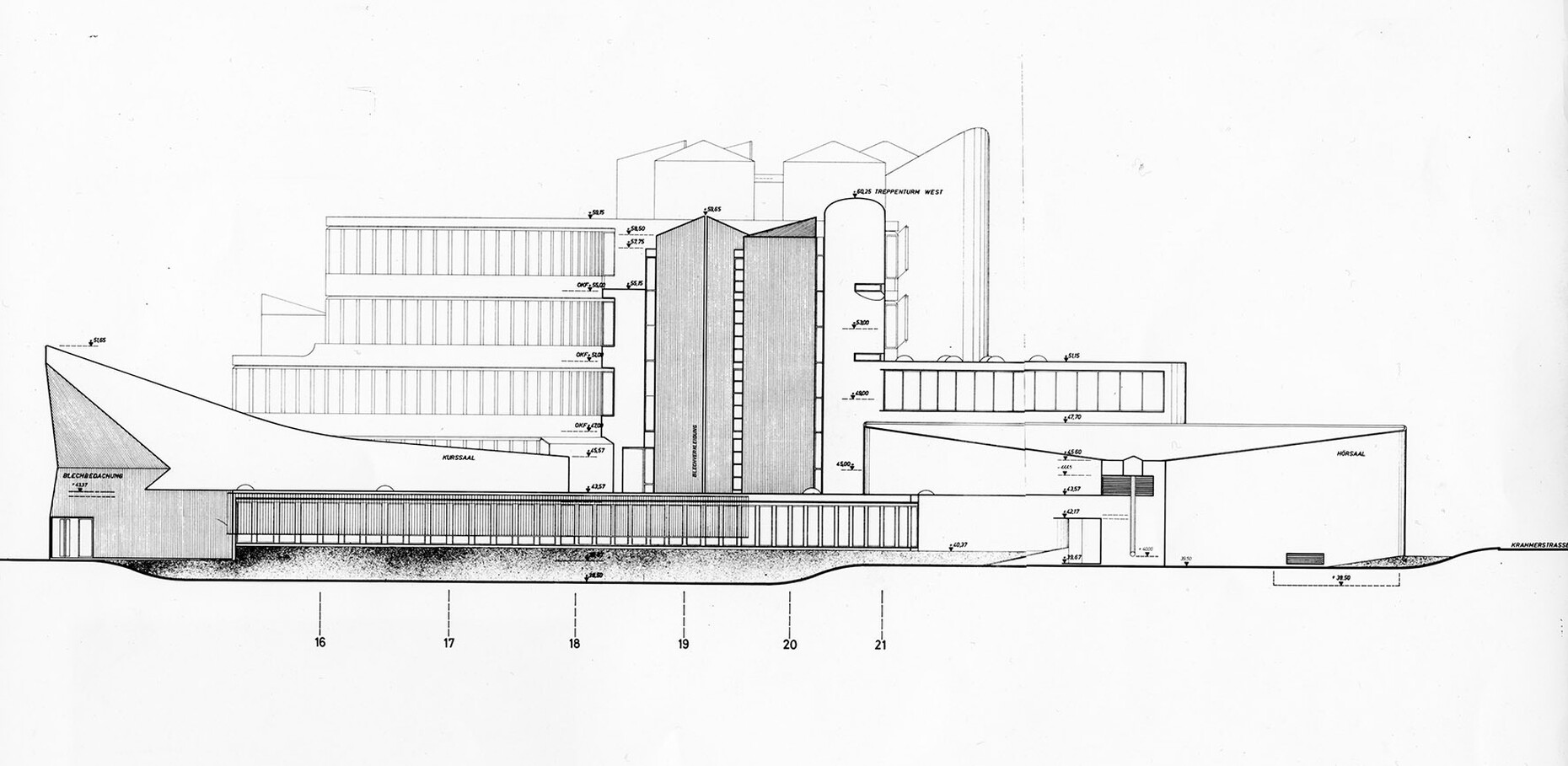

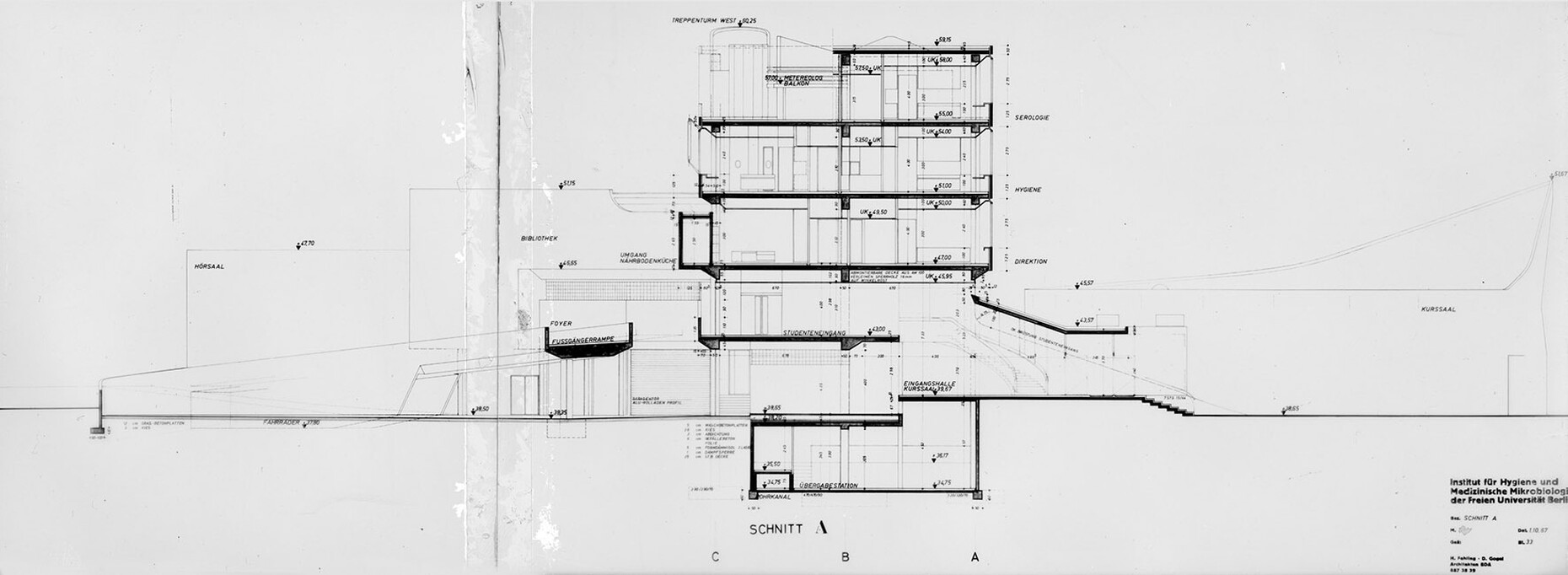

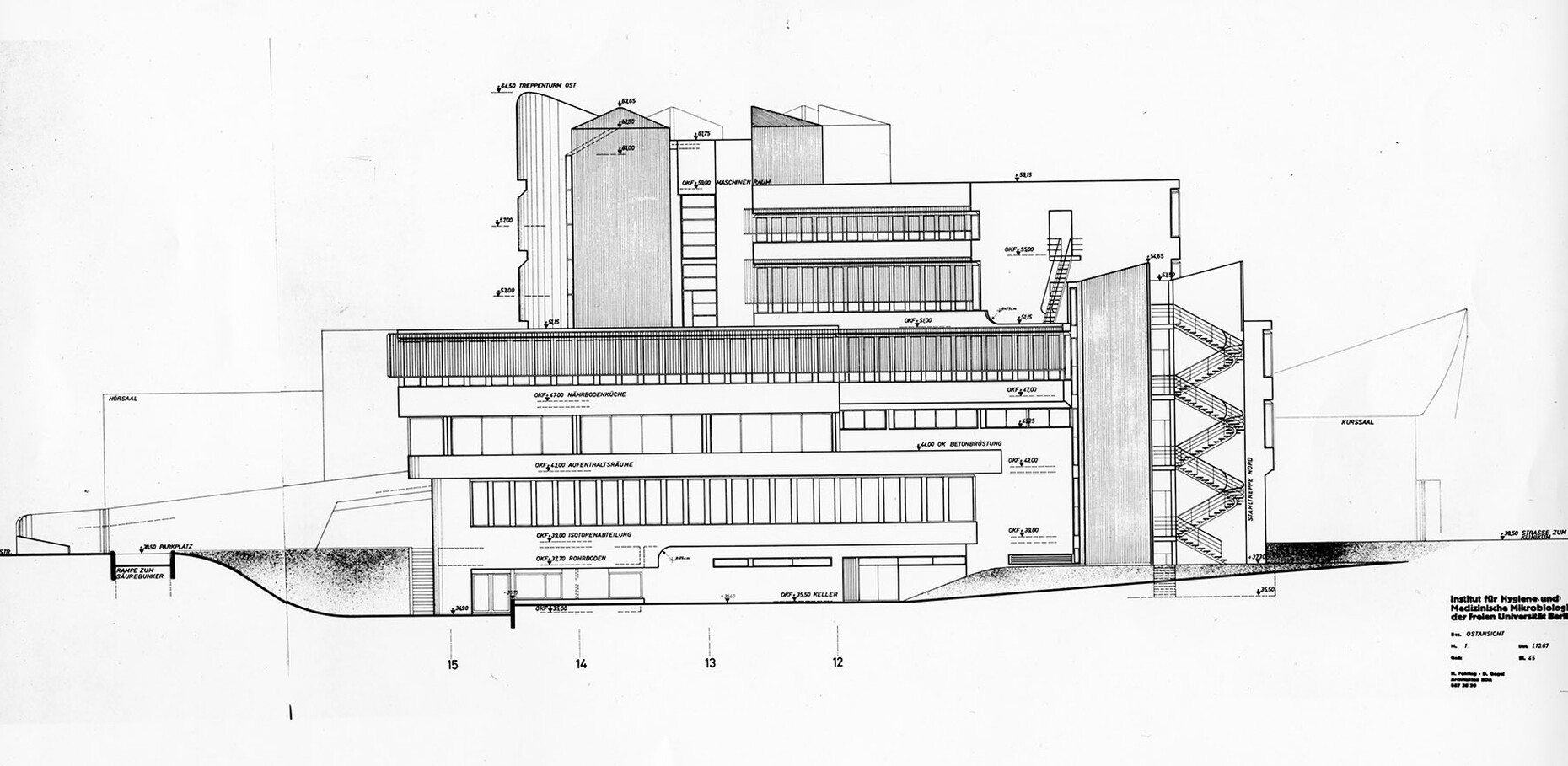

The research institute for experimental medicine at the Berlin Charité teaching hospital, fondly referred to as the mice bunker, and the Institute for Hygiene and Microbiology, located opposite on Krahmerstrasse, are presumably the most prominent sections of the Benjamin Franklin campus in Berlin’s Lichterfelde district. Not far from the Teltow canal, the "mice bunker" was, albeit with interruptions, from the mid-1960s until 1980 the Central Animal Lab at Berlin’s Free University designed and realized by Magdalena and Gerd Hänska as well as Kurt Schmersow, whereas the Brutalist structure opposite was masterminded and executed between 1966 and 1974 by Hermann Fehling and Daniel Gogel.

Both are threatened with demolition. They no longer meet today’s energy consumption standards and can no longer be used adequately in terms of their original spatial programming. We have a group initiated by art historian Felix Torkar and architect Gunnar Klack to thank for the fact that both are now heritage-listed edifices. On Jan. 20, 2021, Berlin’s Senate Administration for Culture and Europe issued the relevant press release. Even beforehand, both buildings were part of the “SOS Brutalism” exhibition that references structures erected in this style and that in part are or were acutely threatened with demolition. However, the fact that in Germany at present heritage listings are not worth more than the paper they are written on was recently proved, among others, by the Free Hanseatic City of Hamburg, where the “City Hof” high-rise ensemble built to plans by architect Rudolf Klophaus in 1958 was scandalously torn down despite having been entered in the Hamburg Heritage List. In other words, the entry of both the above Berlin buildings need not mean they have been saved once and for all.

When it comes to preserving buildings, and this includes those that may at present have fallen out of stylistic favor, there is more involved than merely playing with numbers as regards calculating efficiency. It should initially be clear that when considering the energetic attributes of a building one always needs to include the so-called “grey energy”, meaning the energy inputs that already went into the building in the form of manufacturing the materials used and embedding them in the structure. Not to mention that demolition is always also the destruction of cultural assets: Anyone opting for demolition also destroys such assets.

In other words, the focus is on preserving cultural achievements. Both buildings stand for the time when they were made, and attest to how people thought back then, see the world, and because architecture is always also a reflection of that though, that expression of a view of the world and people. Even if today a building may not appeal to us visually or no longer squares up to its original purposes, this says very little about the actual value of the building in question. Removing a section of the cultural timeline of a society also hardly seems far-sighted in the context of the debates on the issue of reconstruction that still continue to flicker up now and again. We do not know what our grandchildren and great-grandchildren will think about this building which was initiated and realized by our grandchildren and parents. What if they reconstruct what once was a mice bunker for a lot of money? Using what may then be as good as a non-affordable construction material, namely concrete, for which a citizen’s association then hopes to raise at least half the cash from donations, and yet at the end far more tax money is required than expected?

In an open letter, Berlin-based gallerist Johann König and architect Arno Brandlhuber, who also works in the city, breathed new life into the discussion around both buildings on the Benjamin Franklin campus. König runs his gallery in another Brutalist building that is a favorite in the cultural world: the former Catholic Church of St. Agnes, which architect Werner Düttmann designed in 1964-7 in the city’s Kreuzberg district. In 2015, Arno Brandlhuber and his team, for their part, converted the building after it ceased to be used for religious purposes and had stood vacant for a long time into a decisively sober structure.

Together the two now suggest taking over and re-using both the "mice bunker" and the Institute for Hygiene and Microbiology. Be it by leasehold or by purchase and subsequent use for the common weal. Both have in mind something that is nothing less than a new cultural center in Berlin. Studios and exhibition spaces for artists can arise directly adjacent to workspaces for creatives. Annual programs will then present the results of the work and familiarize civic society with the findings. Overarching guidelines will be created to set out the programmatic use of the buildings themselves.

In the process, Brandlhuber and König take their cue from Berlin of the golden post-Unification period, when vacancies resulting from financial difficulties were used by creatives of all kinds and contributed decisively to the appeal of the city. The initiators believe in general the Franklin campus is such a vacant space and the two buildings are in particular. Here, history could again be “presented in a critical vein” here and a contribution made to shaping the future, König and Brandlhuber suggest.

It is a charming proposal. Here, one of those real labs could arise that in recent years many actors have called for, of late the BDA Association of German Architects. The constellation of actors is exciting, and great is the potential. For example, the Charité could become the ideal patron of a thinktank financed by grants and donations as part of the post-pandemic period, where thinking, research, planning and realization would cut across the disciplines, where art, culture and science come to together and in ever-new groupings could be a point of contact for all citizens. A “social gas station” in southwest Berlin, where irrespective of their socio-economic background people can meet and really interact, where in the best of cases there is serious thinking on the future and in all events neither energy devoted to construction or built culture get destroyed.