Spotlight on Women Architects – Lina Bo Bardi

For a long time the architecture of Brazilian post-war modernism, like so many other periods of architectural history, was, in retrospect, a purely male affair – firmly associated with names such as the superstar Oscar Niemeyer, Brasilia designer Lúcio Costa, ingenious concrete constructor Affonso Reidy, hardcore structuralist João Vilanova Artigas and landscape architect Roberto Burle Marx. The fact that this quintet of men actually needed to make room for a woman was only recognised in the course of the 2000s: The Italian-born Brazilian Lina Bo Bardi (1914-1992) provided Tropical Modernism with some of its most impressive buildings, for example her Casa do Vidro (The Glass House, 1952), the SESC Pompéia neighbourhood centre (1977-1986) and, above all, with her MASP, the Museu de Arte de São Paulo (1968).

Achillina “Lina” Bo Bardi was born as Achillina Bo in Rome on 5 December 1914, just after the First World War had begun in Europe. Her upper middle-class parents made it possible for her – as one of very few women – to study architecture in Rome between 1934 and 1940. She completed her studies at a time when another all-destructive war was just beginning in Europe; the second time in little more than two decades. Bo is described as a very self-confident, self-sufficient woman who placed great value on her independence. She founded her own office in Milan in 1940 together with fellow student Carlo Pagani – in all likelihood because without him it would have been even more difficult for her as an architect. However, the work situation during the World War was bad anyway, which is why Pagani and Bo had to eke out a living with trade fair stands and shop furnishings. At the same time, Bo worked as one of Giò Ponti's many unpaid assistants, and she also wrote and illustrated for fashion and architecture magazines. Shortly after the end of the war in 1945, Bo travelled all over Italy taking photographs to document the destruction for Ponti's famous architecture magazine Domus. The suffering of the people she met and the unimaginable extent of the destruction strengthened her conviction that architecture must always serve the common good. She no longer saw a future in Europe, and instead found a soulmate in the art collector Pietro Maria Bardi. She had no desire to actually get married, but with Bardi she came to an arrangement that was to last a lifetime for both of them. As part of this arrangement Bo wasn't required to give up her surname, but placed both surnames equally behind her nickname: Lina Bo Bardi. Together they emigrated to Brazil in 1946.

The two got to know Brazil as a young, aspiring and socialist state that offered them the distance from destroyed Europe they longed for. Together, the Bo Bardis first organised three large, successful exhibitions of European art. Pietro had travelled regularly to South America since 1933 and had good contacts with artists, politicians and architects. Then he met the media mogul Assis Chateaubriand. With him, he developed the idea of an important new museum for modern and classical art in São Paulo, the MASP (Museu de Arte de São Paulo). Chateaubriand was responsible for the finances and the necessary contacts, Pietro was in charge of putting a collection together and Lina was in charge of converting a plain office floor into a museum. This was to be the home of the new museum for the first few years, before funding came together for the spectacular new building that Lina Bo Bardi developed for the MASP from 1957 onwards: Located directly on the Avenida Paulista, one of the city's main arteries, she suspended a rectangular, almost completely glazed structure from two enormous reinforced concrete beams that rise like bridges above the building, allowing it to hover a good ten metres above the ground. This created a public square underneath, covered by the museum, where all kinds of events could take place. To further emphasise the dramatic nature of the gesture, Bo Bardi had the two concrete beams painted a bold red. When the museum was ceremoniously opened in 1968, it was a sensation – and it certainly still is today. Pietro Bardi remained director of the MASP until 1996, three years before his death.

In its drastically modern language, however, this design is an exception in Lina Bo Bardi's work. In the many other houses and furniture she designed, she preferred to look for connections with local building and craft traditions instead of pure, radical modernism. As early as 1951 she accepted Brazilian citizenship with complete conviction – she was finished with Europe. And as late as 1991 she said in an interview that “I don't remember Italy, and it doesn't interest me in the slightest.” With the empathy and curiosity of the immigrant, she now explored her new homeland and always incorporated traditional motifs and local materials into her modern designs. An outstanding example of this is the Casa de Vidro, the Glass House, which she set up as a new home for herself and her husband as early as 1952 on a steeply sloping and densely wooded plot of land in São Paulo. She responded to the steep topography with a radical, single-storey house slab, which she set horizontally into the slope. From the street the house thus appears to be a simple pavilion, but downhill it stands on eleven narrow, increasingly higher stilts between the almost equally narrow trees. Bo Bardi also placed an open courtyard in the centre of the house, through which the dense underlying vegetation could grow. And it was not only the native flora that permeated the European-influenced modernism of the house in this design: Bo Bardi had the craftsmen insert coloured pebbles and ceramic shards into the concrete walls to break up the concrete's harshness.

These motifs run through Bo Bardi's large, diverse body of work as an architect. In the tradition of European modernism, she sought connections between the interior and exterior, fluid transitions with large windows and designs that mediated between the building and the green space around it. The houses she designed are surrounded by gardens, verandas, terraces and courtyards, and the structure of the different layers of space, which are connected with sliding elements and large windows, is sometimes reminiscent of the complex spatial constructions of Japanese architecture. In terms of materials, Bo Bardi repeatedly used unprocessed tree trunks that she found in the immediate surroundings, as well as clay, traditional roof tiles, pebbles and ceramic tiles. Sometimes she came very close to folkloric, Afro-Brazilian architecture, which she studied on trips to northern Brazil. But Bo Bardi always managed to avoid becoming nostalgic or romanticising in her projects. The oversized windows, the seemingly frameless glass panes and the fine iron handrails are always a reassurance that her work is decidedly contemporary architecture.

Yet from today's perspective, another aspect of Bo Bardi's work seems all the more important: While most of her architect colleagues always strove for new buildings, Bo Bardi devoted herself early on to the preservation and conversion of existing building culture. In 1958, for example, she had to find a suitable location for a new museum for modern and Indian art in Salvador do Bahia. She decided on a centuries-old building complex that had been rebuilt several times and had a wonderful view of the Bay of All Saints. With minimal intervention, she had this complex converted into the Museu de Arte Moderna da Bahia (MAM). She gutted the existing structure, removing everything unnecessary, and made new connections. In the centre she placed a sculptural spiral staircase that looks as if it has been pieced together from raw boards hewn by local craftsmen. The Dutch architect Aldo van Eyck was still ecstatic about it in 1995: “This staircase is an event! It does something to people, everyone looks noble here. It does not dictate the path, but stimulates and guides with elegance. This is not a staircase, but a miracle!”

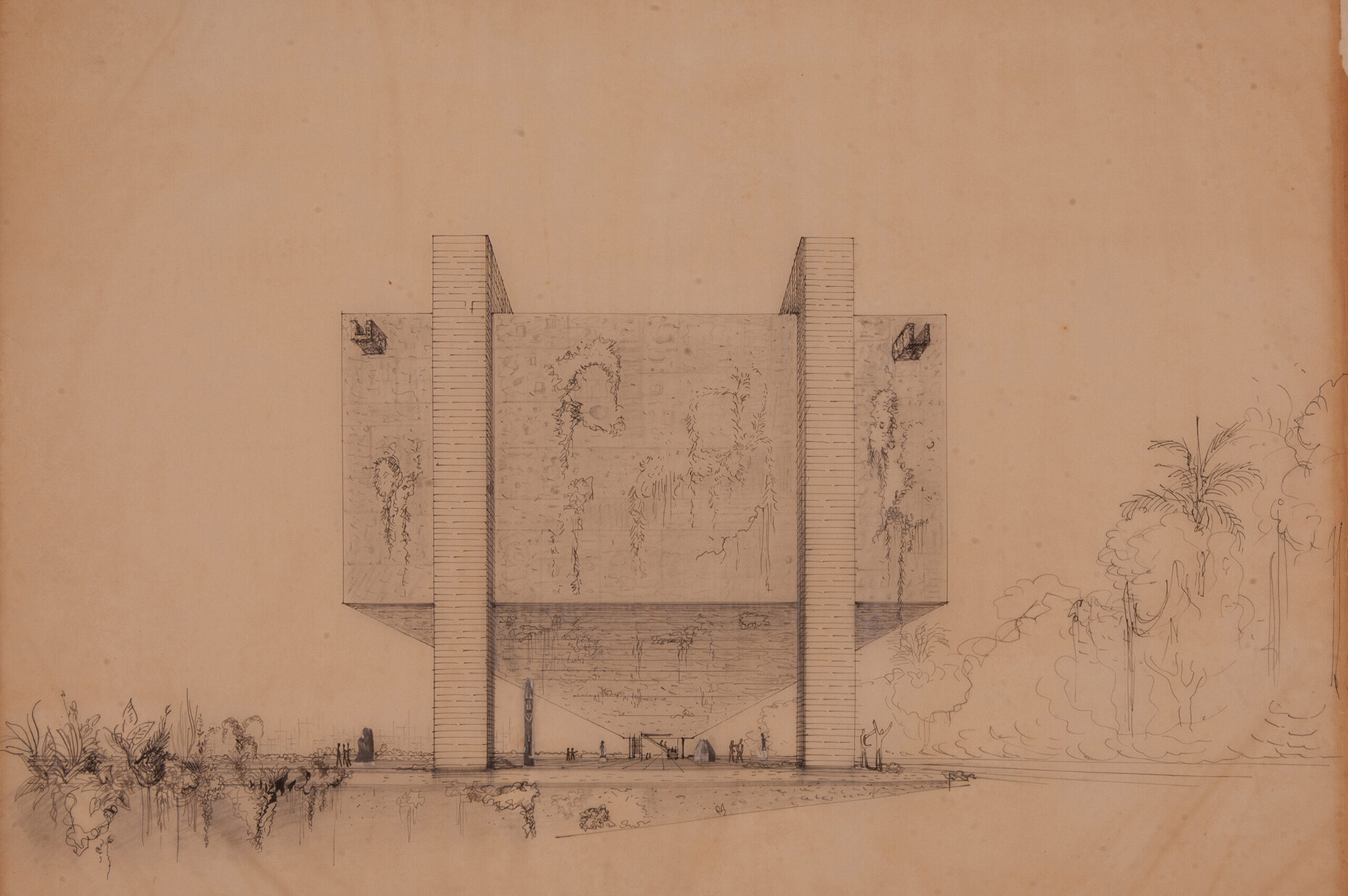

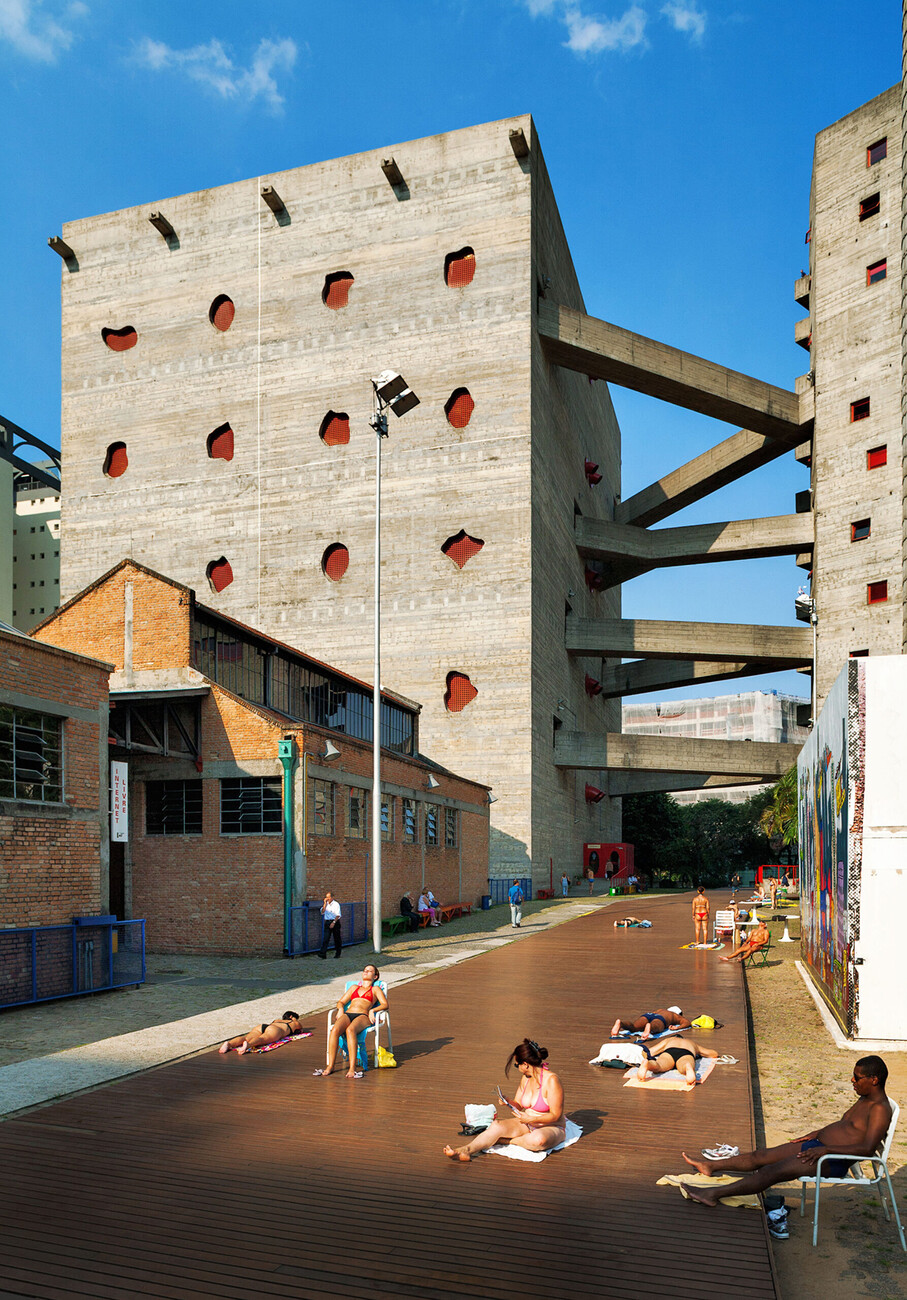

The military coup in Brazil in 1964 initially put an abrupt end to Bo Bardi's work on public commissions. As in Italy, she had also expressed herself politically in Brazil. Three major projects of hers thus remained unbuilt, while she worked mainly on exhibitions, film and theatre projects. Her husband remained director at MASP and Bo Bardi was commissioned in 1977 to demolish the enormous old SESC Pompéia factory in a poor district of São Paulo and build a modern sports and leisure centre in its place. She never considered demolishing the building, however, but instead investigated how this relic could also be preserved with little intervention and transformed into a symbol of change. Next to the enormous chimney, she placed two mighty new buildings with exposed concrete façades: a twelve-storey tower and a roughly ten-storey cuboid with completely irregular window openings that can be closed from the inside with rough sliding, bright red wooden elements. She extended distinctive concrete bridges between the two buildings, on which users of the stacked sports fields and swimming pool can visibly walk back and forth. She filled the remaining halls of the old factory with a spatially distinctively and generous new structure of brick and concrete, into which she inserted all conceivable forms of event halls, stages, meeting places, assembly rooms and a district library. Bo Bardi even designed the poster for the centre's opening in 1986 herself: Flowers now sprouting from an old chimney. From a symbol of industrial labour, she created a building for festive, social togetherness using great imagination and few resources.

Lina Bo Bardi died on 20 March 1992 in her Glass House in São Paulo. Why her projects were not counted among the canon of modern Brazilian architecture for so long remains a mystery. Perhaps her architecture was not “pure” enough for this, because she always developed her ideas of a modernity that improved all areas of life, using local objects and in direct exchange with the people on site. In doing so she placed social, political and cultural commitment above “pure doctrine”. As late as 2010, when her work was to be shown at the Venice Architecture Biennale as part of the main exhibition, the Brazilian photographer Nelson Kon was sent to photograph her buildings – many of which had never been documented before.

Tip:

Lina Bo Bardi – The poetry of concrete

Tchoban Foundation. Museum for Architectural Drawing

Christinenstraße 18a

10119 Berlin

Opening of the exhibition on 31 May 2024 at 19:00

Exhibition duration: 1 June – 22 September 2024

Opening hours:

Mon to Fri 2 – 7 pm

Sat to Sun 1 – 5 pm