NEW WORK

Between disciplines

Alexander Russ: You are Professor of Integrated Product Design at the TUM School of Engineering and Design. What does that mean?

Dr. Katja Thoring: I am a product designer myself, but my chair is part of the Department of Architecture at the Technical University of Munich. That's why my teaching is strongly embedded in an architectural context and moves between architecture, interior design and product design. This entails a very interdisciplinary way of working. Product design often acts as a kind of interface.

What can product design contribute here?

Dr. Katja Thoring: I am heavily involved in human-centred design. This includes, for example, conducting interviews with the future users of a building before starting on the architectural design. In my opinion, starting from people's needs is not yet so widespread in architecture. However, students are very interested in this. That's why I think it's important for future architects to understand furniture design and typography in order to meet these needs in a holistic way. I previously taught at the Anhalt University of Applied Sciences in Dessau. The design education there is strongly oriented towards the Bauhaus, in whose immediate neighbourhood the university is located, and ultimately the basic idea of this school is more relevant than ever: that different disciplines enrich each other.

Do you also exchange ideas with experts from disciplines other than architecture?

Dr. Katja Thoring: There are various integrative research centres at TUM that help the different disciplines to network. Together with my colleague Prof. Annette Diefenthaler, I am currently in the process of setting up the Munich Design Institute at the Garching Research Centre within this framework. This is a research institute that deals with design topics, but is in dialogue with other disciplines such as robotics, medicine or computer science and players from industry.

Can you give some specific examples?

Dr. Katja Thoring: There are various interdisciplinary projects in teaching. For example, we carried out a lead user analysis together with Prof Dr Henkel from the Dr Theo Schöller Endowed Chair of Technology and Innovation Management and the manufacturer Steelcase . To this end, the students conducted around 100 interviews with potential users in order to identify people who are of interest to Steelcase as a target group. The focus was on topics such as inclusion in the office and neurodiversity. We wanted to find out what framework conditions users need in order to be able to work well. In a current BMBF-funded research project, we are collaborating with a data science company. Together, we are trying to develop interactive decision-making spaces for SMEs. Specifically, we are creating a combination of a physical space, an interactive table as hardware and data-driven software. Different disciplines are therefore coming together here: Interior design, product design, interaction design and computer science.

Your seminar ‘Product Seeks Manufacturer’ deals with the question of what students need to learn in order to gain a foothold in industry. Do you also work together with other disciplines?

Dr. Katja Thoring: Yes, we cooperate with students from the fields of architecture, mechanical engineering, human factors engineering, mechatronics, business informatics and robotics, among others. We organise the whole thing in groups so that there is as much exchange as possible. Each group is assigned a manufacturer whose portfolio is analysed. This allows the students to find out what the brand's design philosophy is, how the company manufactures its products and whether there is perhaps a gap in the market. A specific object is then designed and manufactured on this basis. Thanks to the TUM MakerSpace and its workshops, we have the opportunity to realise this professionally. The result is a market-ready product that could actually go into series production. In principle, it works just like an author designer would do.

One focus of your research work is on the topic of ‘creative workspaces’, i.e. the design of workspaces that are intended to promote creative work. Can you tell us more about this?

Dr. Katja Thoring: We have two so-called ‘creative space labs’ at our department. One is dedicated to teaching and the other to research. The basis is a modular wall system that comes from exhibition stand construction. We can use it to build different scenarios and test the product designs very specifically in the interplay of space and object. In research, we often work with cameras and sensors that record what is happening in the room. We observe people and measure their heart rate, for example. This allows us to analyse how people interact with the product in question.

How does it work?

Dr. Katja Thoring: When designing spaces and products, there is always a basic hypothesis as to what they trigger in users. With the Creative Space Labs, we can test whether these hypotheses are correct. As part of Munich Creative Business Week 2024, for example, we conducted an open office experiment with 30 participants in three room scenarios. The first scenario was intended to have an activating effect, which is why we furnished the room with yellow walls and furniture that is used standing up. The second scenario focussed on relaxation. Therefore, sofas and a rather bluish colour spectrum were offered. The third room scenario, on the other hand, was kept very sober in grey and white tones. This ‘neutral’ room served as a reference room for comparison with the other two rooms. We invited the participants to work in the respective scenarios and measured the whole thing while they did so. We then analysed the data anonymously with the help of artificial intelligence.

How exactly do you use artificial intelligence?

Dr. Katja Thoring: There are various AI models, some of which are available as open source. We then adapt these models to certain parameters. For example, there is an AI model that can be used to record the specific movements of a person in a room. Other AI models analyse interaction with objects, for example how and how often a person uses an office chair or desk. Another model uses facial recognition to analyse how the room scenario affects the respective users, for example whether they are relaxed or concentrating on something.

Difficult question: What do you think the ideal workspace looks like?

Dr. Katja Thoring: It depends on how I want to use the space. For creative work, I need a completely different environment than if I want to concentrate on solving problems. When developing ideas, it's helpful if I can look out of the window in a relaxed sitting position and enter into a dialogue with my surroundings. Organic shapes and natural colours are also beneficial here. When it comes to problem solving, windows tend to interfere because any form of distraction has a detrimental effect on concentration. Therefore, such rooms must also have good sound insulation. The colours here should have a stimulating effect, which is why red and yellow tones are well suited. Ideally, the working environment should offer a utilisation concept that allows several scenarios to be implemented simultaneously.

According to the industry, office furniture should be as flexible and cosy as possible. Is this the future?

Dr. Katja Thoring: Flexibility is important, but it's not a panacea. Furniture that can do a bit of everything won't work in the end. In my opinion, the whole thing can be solved architecturally by designing different rooms that are optimally suited to a specific activity. This also applies to the furniture that is used in these rooms, which should be precisely tailored to the specific use. In my teaching, I am currently working on hyper-specific spaces. Our students have the task of designing an environment for a very specific activity. These are, for example, rooms in which programming takes place or which are used for debating. The underlying room volume is always the same. We experiment a lot with sensory properties, ranging from visual perception and acoustics to smell and taste.

In work environments, desk sharing is the exact opposite, because employees no longer have a fixed workplace. What do you think of this concept?

Dr. Katja Thoring: The concept goes hand in hand with a reduction in office space and an increase in working from home, which is why there are usually fewer workstations than employees. The whole thing must therefore be structured in such a way that there is no overcrowding. So first of all, you need an intelligent utilisation concept. But even if this is the case, it removes the possibility of personalising the workplace. From a creative point of view, the whole thing can have a stimulating effect, because I'm always forced to interact with new people. Nevertheless, I doubt that it helps employees to identify with their workplace. But that is also a new task for us designers, because we have to design objects that enable users to personalise their working environment to a certain extent.

On the other hand, there is the home office, where private and professional life are completely intertwined. Do you also deal with this topic?

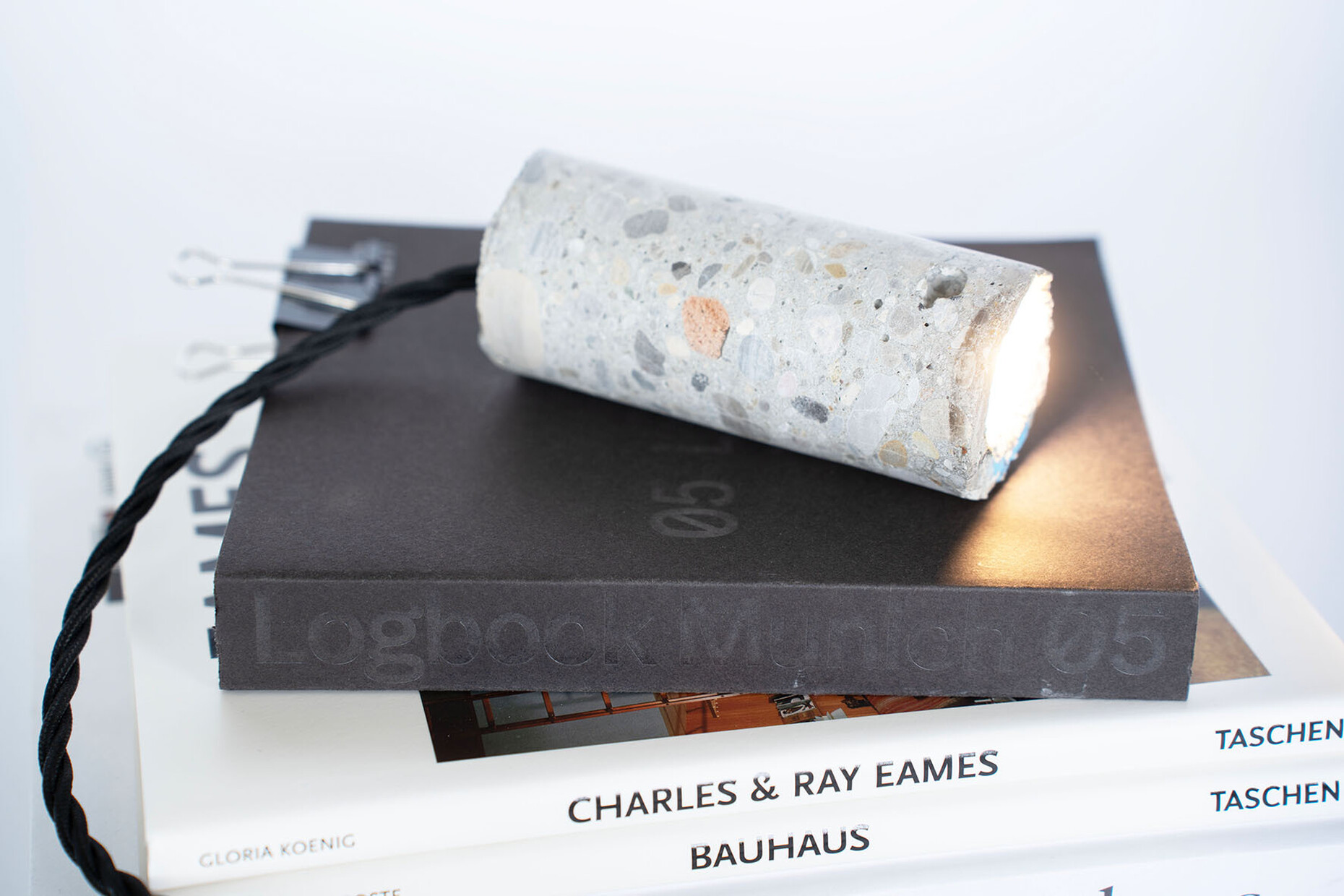

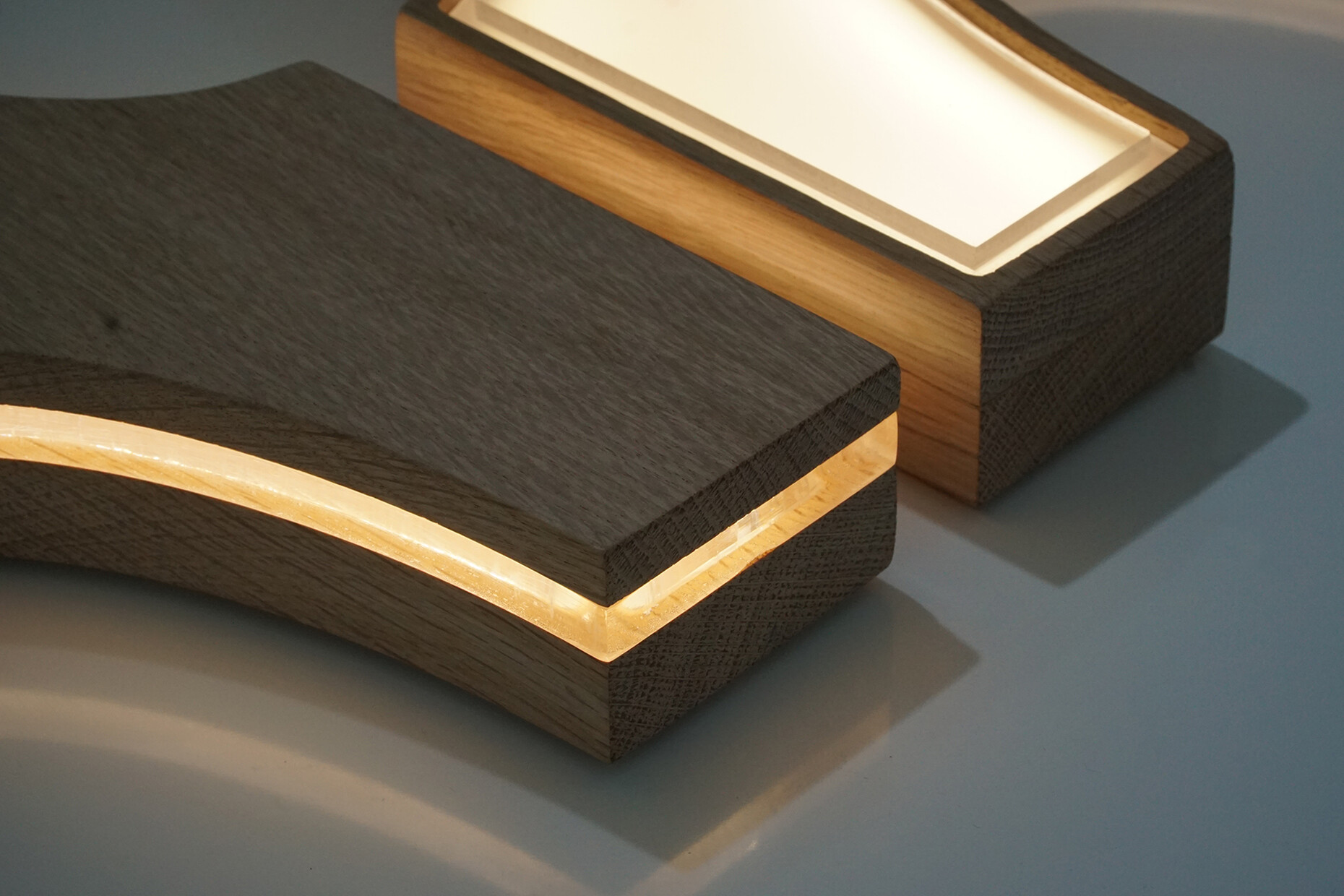

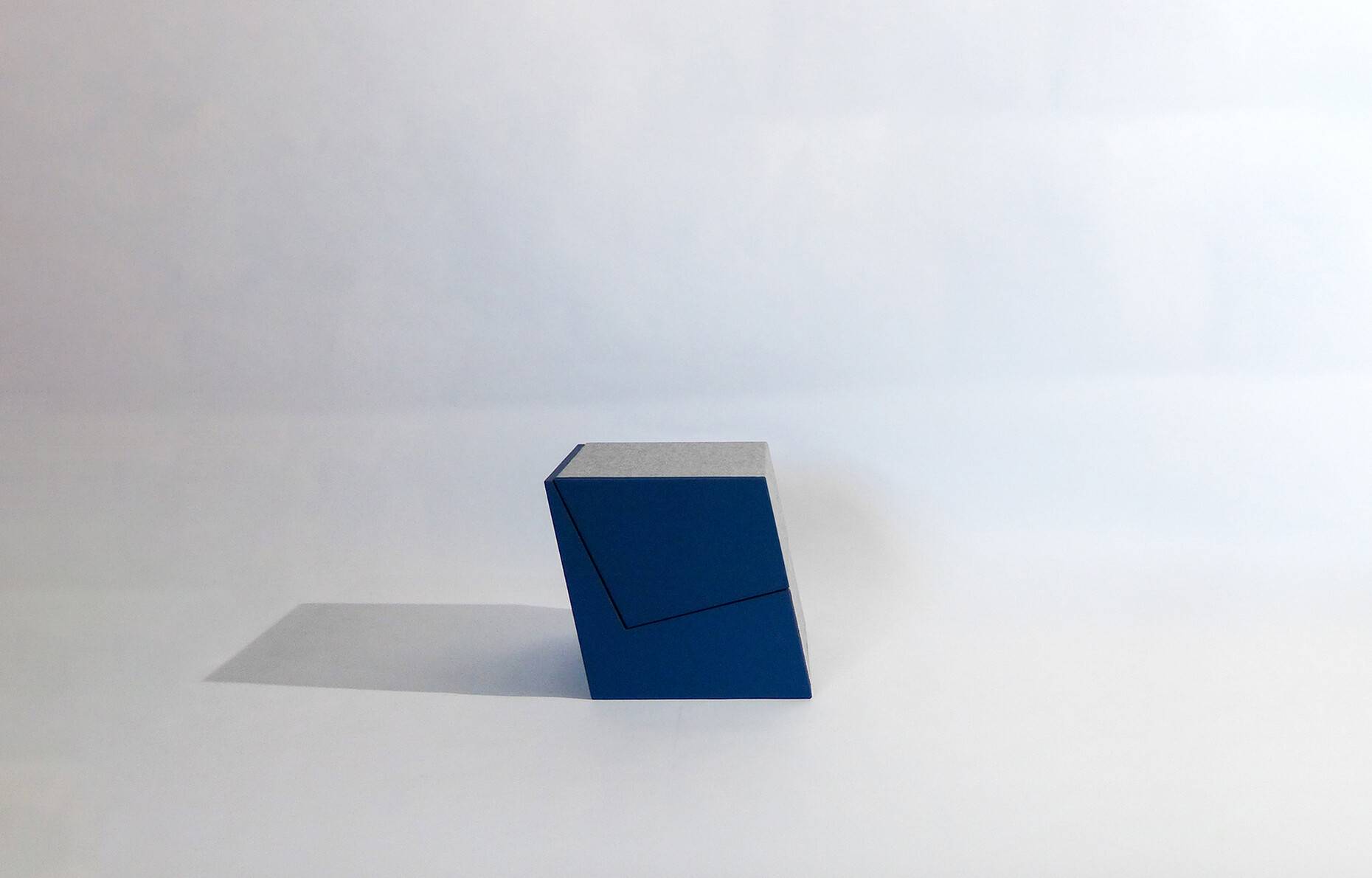

Dr. Katja Thoring: Yes, last year, for example, we carried out a study project on the topic of ‘Tiny Homeoffice’. Here, the students developed objects for working at home in the smallest of spaces. The results include, for example, stools, side tables and table legs that were developed according to the origami principle and can be folded flat. Another project is a light installation above the desk, which can be used to set different scenarios - from daylight, which has a revitalising effect, to indirect atmospheric lighting. A triangular stool-table combination has also been created, which can be placed in the corner of a room due to its geometry and therefore takes up little space.

Working environments are increasingly being planned as informal places that are to be used for communication and informal exchange. Does this make sense?

Dr. Katja Thoring: That's certainly a good strategy, but of course it can't replace everything that's lost by working from home. In my opinion, a major problem is the informal transfer of knowledge, i.e. how colleagues learn from each other in everyday exchanges. This concerns, for example, the familiarisation of new colleagues or the exchange of experience between younger and older colleagues. This doesn't happen over a latte macchiato at a fancy café counter, but during everyday work. This is certainly the main task for employers and office planners: How do I make working environments attractive so that people come back to the office to learn from each other?