"I want to see architecture that isn't boring"

Florian Heilmeyer: Madame Buczkowska, you were born in Sopot, a small town on the Polish Baltic coast close to Gdansk. Do you remember when and why you started to want to become an architect?

Iwona Buczkowska: Yes. When I was at high school, I received a gift from a family friend living in London. It was a magnificent book, very large and well illustrated; “Art treasures of the world” it was called. It was a type of book that simply didn’t exist in socialist Poland, plus to see works from the West was very rare. A few images particularly caught my attention: The chapel in Vence decorated by Henri Matisse, Notre-Dame-du-Haut in Ronchamp by Le Corbusier, and the Fallingwater House by Frank Lloyd Wright. The book allowed be to discover the abundance of various civilizations around the world in painting, sculpture, architecture. I wanted to participate in that trove of diverse creations.

Was there an architectural tradition in your family?

Iwona Buczkowska: No, not at all. First, I wanted to study Arts. But my parents considered it very difficult to survive as an artist. They advised me to study Architecture at the Polytechnic in Gdansk, where I started in 1972. After that the plan was to continue my studies at the Beaux Arts. This is what I would have done if I had not received my scholarship for France.

Was it hard to persuade your family that you would study Architecture?

Iwona Buczkowska: No. It was not unusual for women in Poland to study Architecture. There were many women studying it. The difficulty was college admission. You had to pass a difficult exam and there were five candidates for one place. There were 50 students in my class, although only seven were men. Then barely two women managed to set up their own practices...

In 1973, in your second year of studying, you seized the opportunity of a scholarship for the École Spéciale d’Architecture in Paris. What made you want to leave?

Iwona Buczkowska: Despite some periods when the stores were empty, I was happy in Poland. Unlike many other socialist countries, membership in the Party was not obligatory, the universities were independent, and you could travel, although organizing travel was difficult. During high school I had already worked as an au pair in Oxford. But at the same time, I was fascinated with different cultures. I dreamed of traveling through the world, my bedside book was Rudofsky’s “Architecture without Architects”. So when I got the chance to leave, I left. My curiosity, my interest in art, it was kind of a challenge. And Paris was a legendary city, the perfect choice for fulfilling a young person’s dream.

You went to Paris and landed straight in the class of Renée Gailhoustet, a French architect well-known for her groundbreaking social housing projects in Paris’ banlieues. What did you learn from her?

Iwona Buczkowska: Renée Gailhoustet passed on to me her thirstfor researching unusual solutions, that you need to take a risk with your designs, and perseverance in developing projects and defending them.

What other influences were important during your studies?

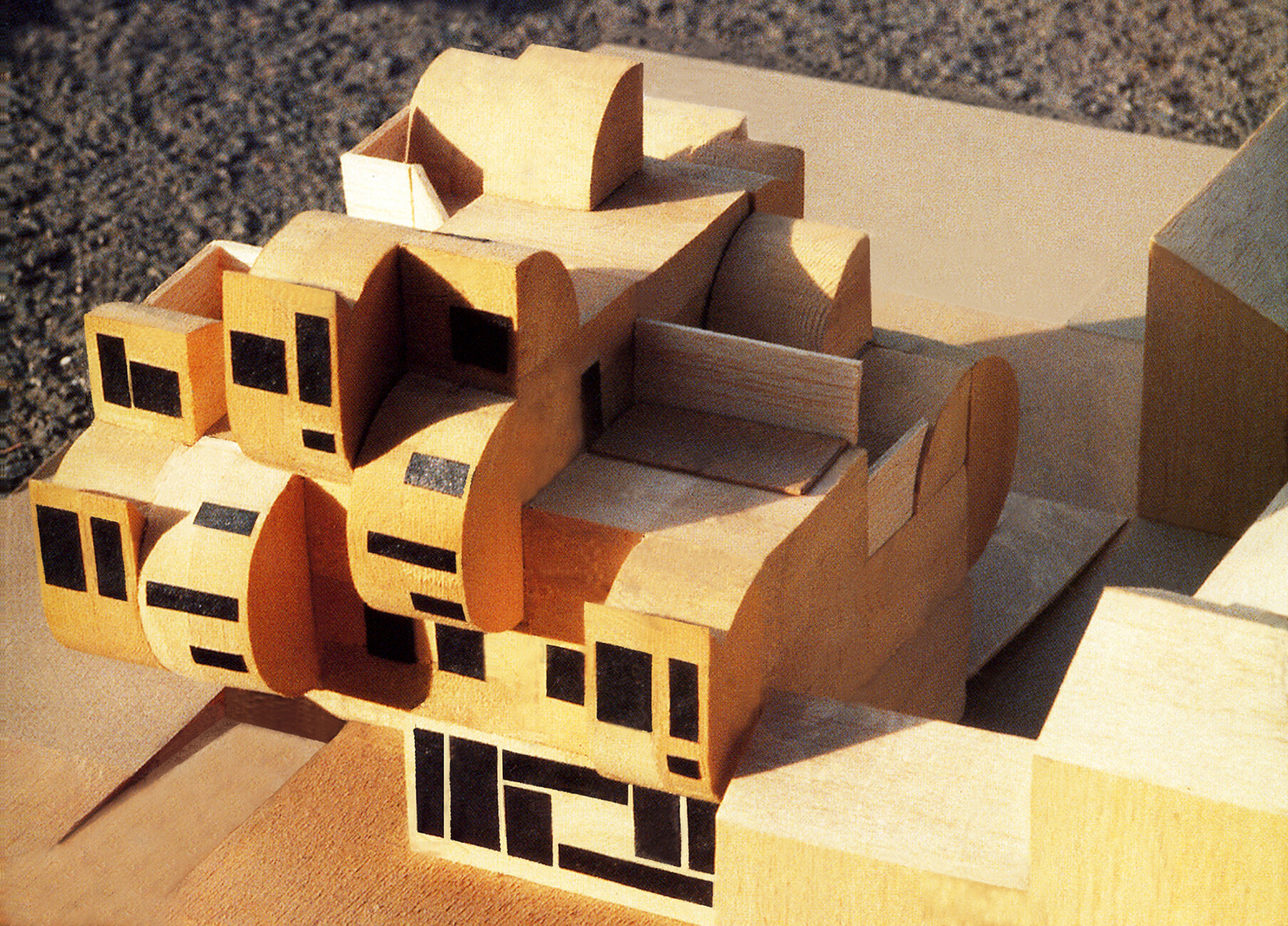

Iwona Buczkowska: As soon as I arrived in Paris, my class went to visit a construction site in Ivry. It turned out to be Les Étoiles d’Ivry, a social housing project designed by Jean Renaudie. It was a shock to me. I was very impressed by the freedom of the architect’s vocabulary, by the expressive force of the buildings, which avoided any of the orthogonality in which I still believed at the time, at least for housing. So I started to discover the freedom of architectural expression in the horizontal planes of the jagged geometries of Renaudie and Gailhoustet. Also I discovered the freedom of expression in the vertical oblique planes of Claude Parent and the importance of load-bearing systems in the space frames by Yona Friedman and in the tensegrity structures by David Emmerich. It seemed there were infinite possibilities. I tried to find my own path through the use of oblique constructive frames or supporting arches in connection with free floor plans.

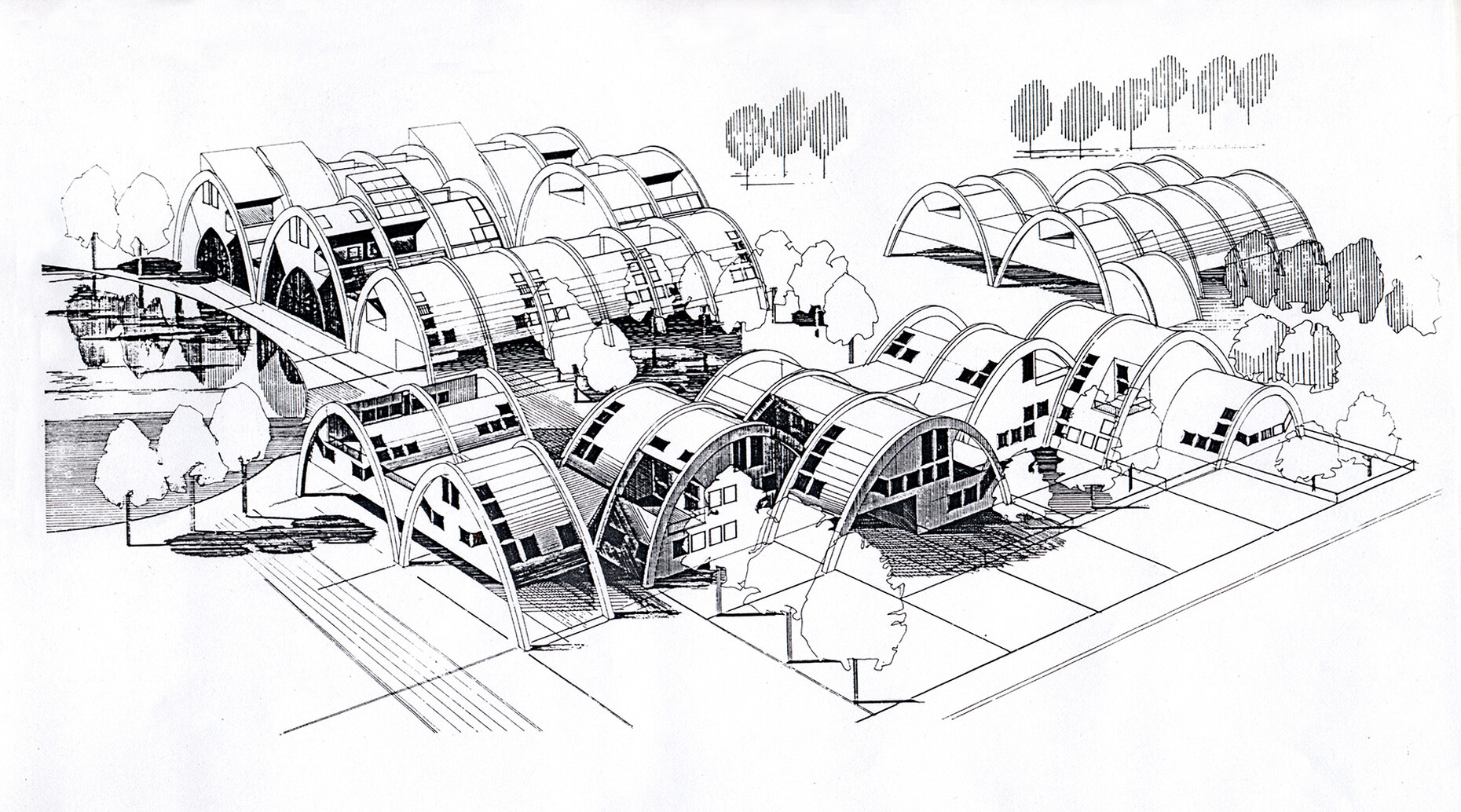

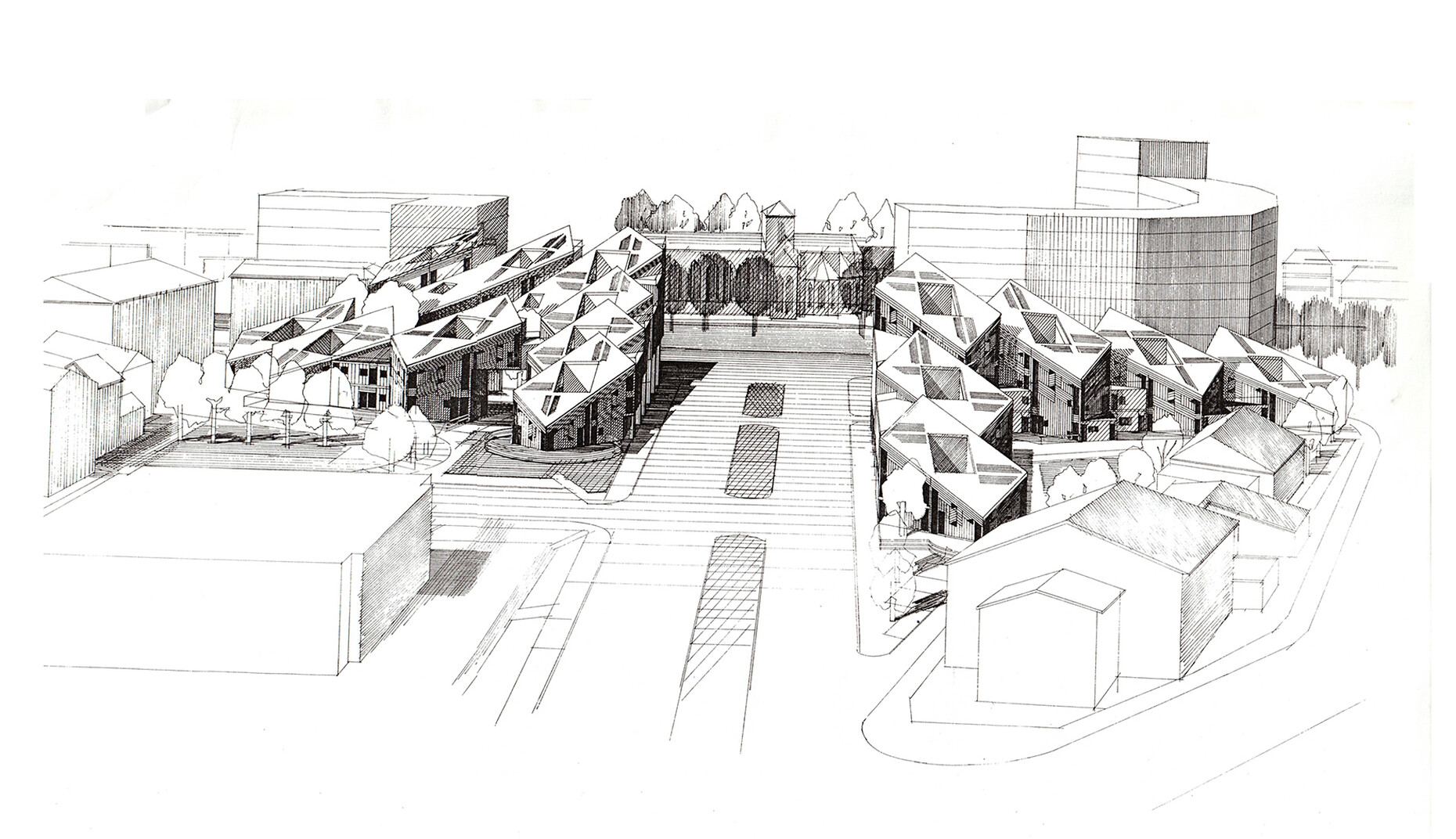

Immediately after graduation in 1978 you started on your own project, a social housing project in Le Blanc-Mesnil, also a suburb of Grand Paris. How did that happen?

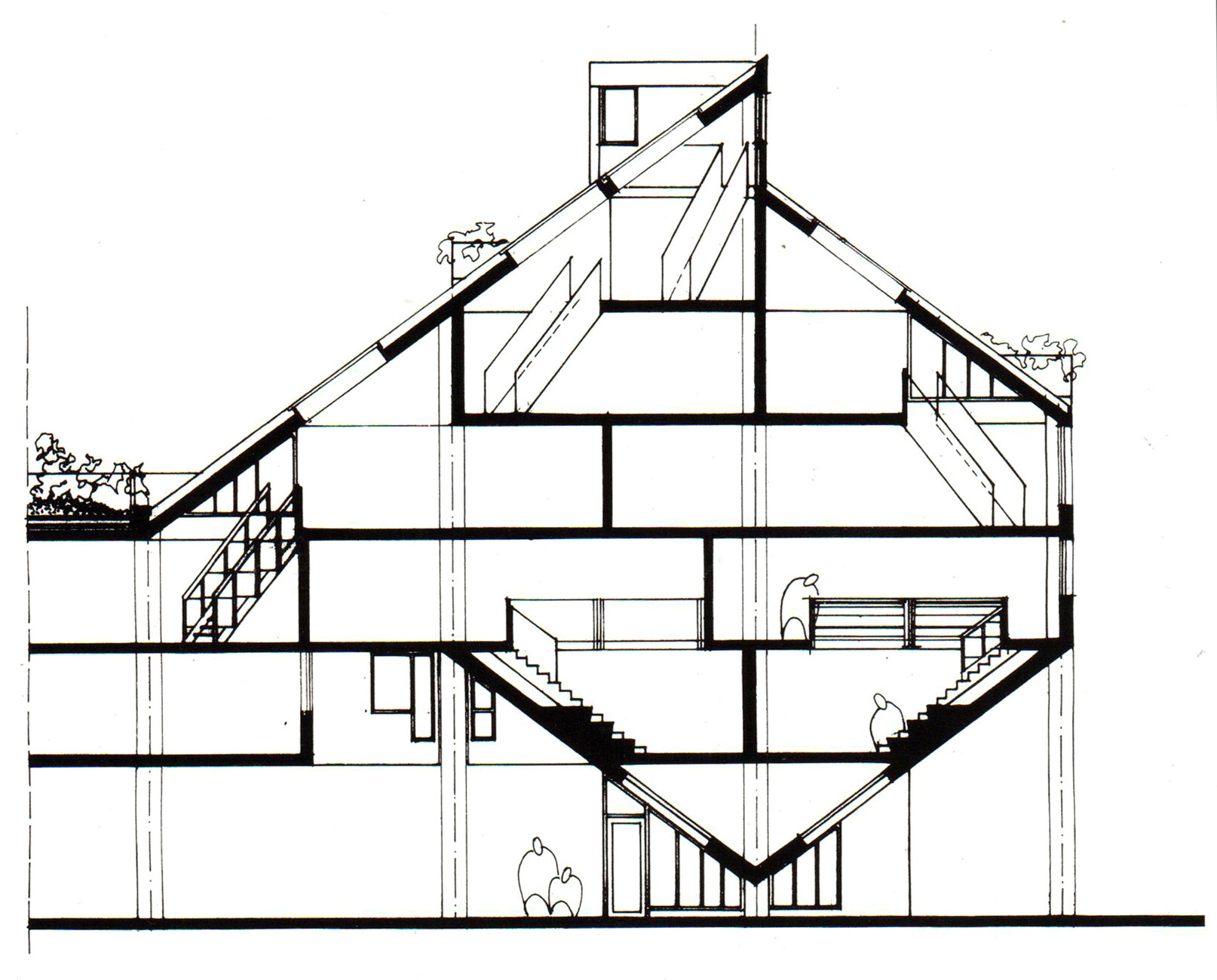

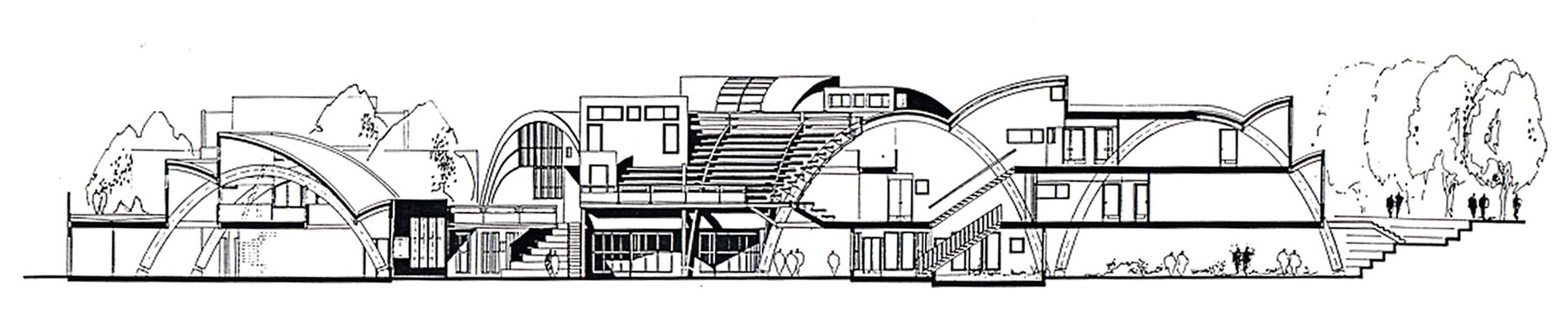

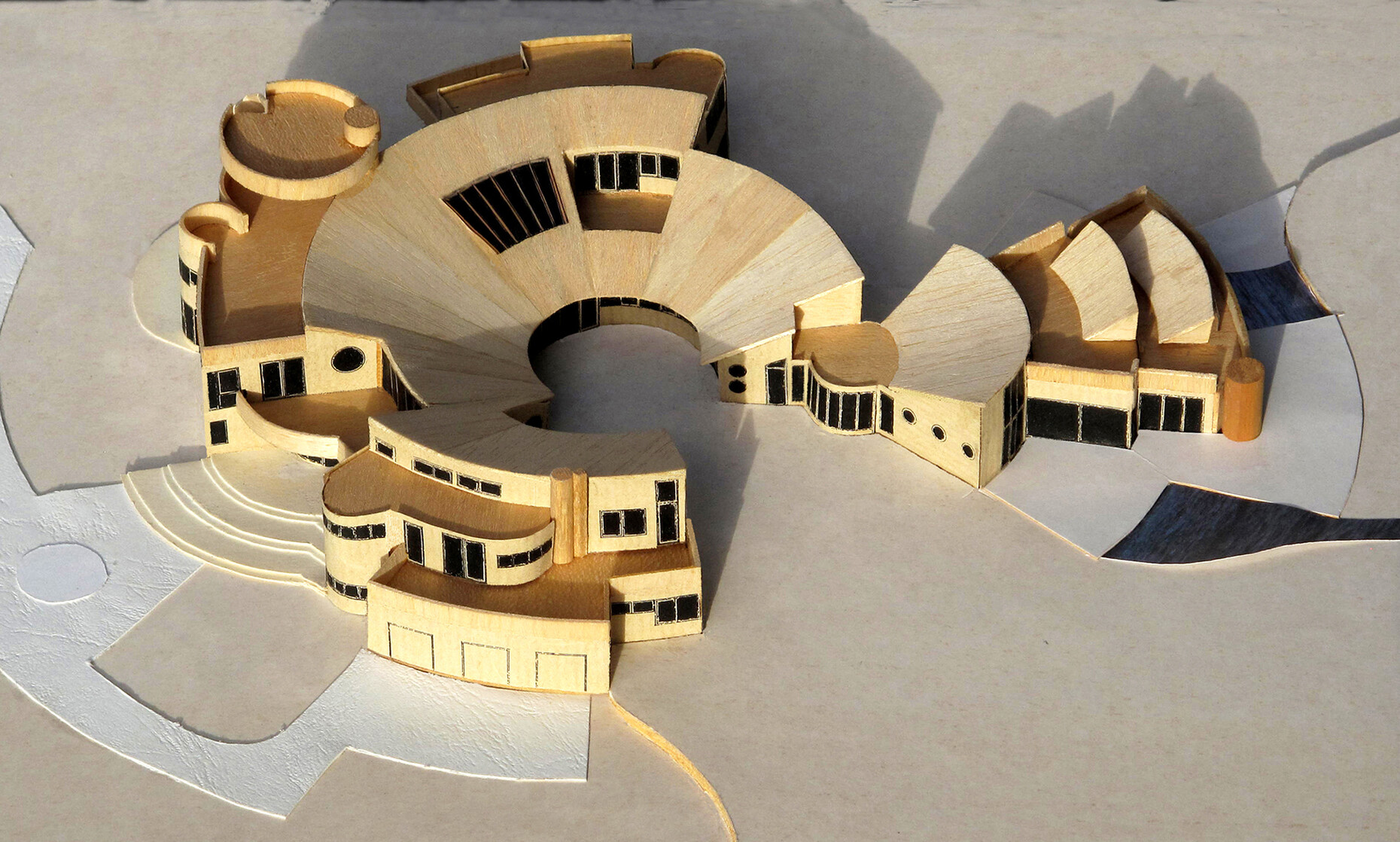

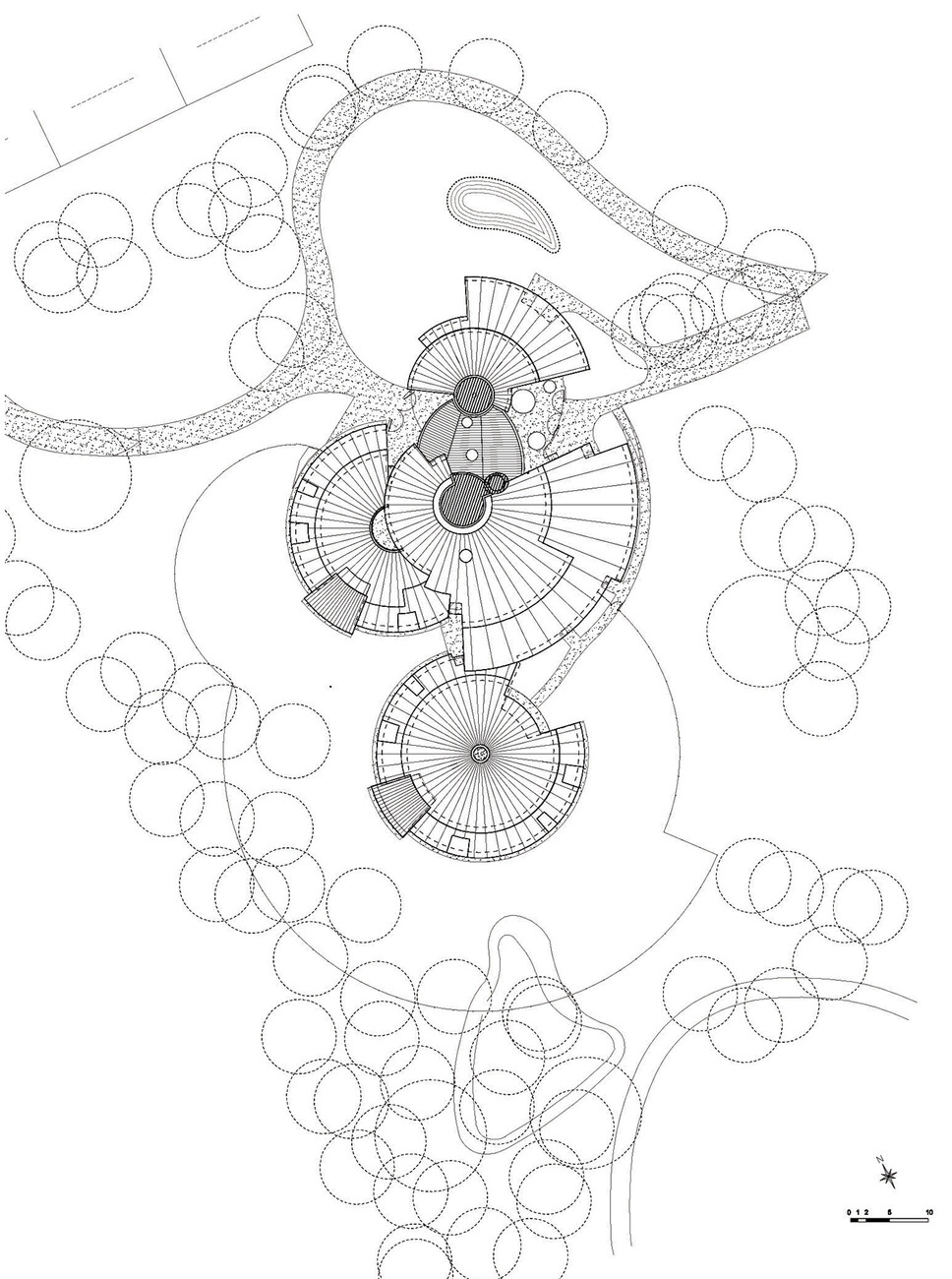

Iwona Buczkowska: I was very lucky. My graduation project was a housing complex across the street from the Basilica of Saint-Denis. I took inspiration from the basilica’s Gothic arches and flying buttresses, and structured my proposal around some vertical, concentric arches with apartments and offices plugged into the upper floors and snaking pedestrian passages at the ground level. For the final evaluation, Gailhoustet invited a deputy director of the social housing developer for that region, Jean-Pierre Lefebvre. He offered me a small project, to design 20 housing units on a site of abandoned orchards next to the train tracks in Le Blanc-Mesnil. In the wake of my first designs, the project grew to a dimension of 225 housing units.

You were still very young and unexperienced. Were you nervous about the commission?

Iwona Buczkowska: Yes and no. It happened step by step. I accepted the offer to study 20 housing units. And my worries were not as strong as my awareness that this was an unprecedented situation which would never be repeated. It was an extraordinary adventure, completely unforeseen and exceptional, that life offered me.

How about the other parties involved. Did they easily accept a young Polish woman as architect for a project that size?

Iwona Buczkowska: It was difficult sometimes. I remember sitting at the table for a first meeting with all stakeholders. After about 20 minutes, I asked why we didn’t start with the meeting. They told me they were still waiting for the architect to arrive.

You also proposed timber as the main material for the housing complex. Wasn’t that a highly unusual choice back then?

Iwona Buczkowska: It was extraordinary to build social housing in wood. In France at that time, wood was something associated only with mountain chalets. But mine was a very deliberate choice based on an in-depth analysis of the site in Le Blanc-Mesnil, where timber existed as a common building material – it was just carefully hidden in the attics. Then the scale of my buildings clearly needed lighter, finer structures than concrete could offer. A concrete post for my structure would have been 30 by 30 centimeters instead of 14 by 14 centimeters the same structure in timber. I was deeply convinced that we needed to explore materials other than those used out of habit. Of course, there is a risk of making mistakes. But wood with its richness of possible processings and the warmth of the material was the perfect choice for the objectives of this project.

How did you convince everyone else of wood?

Iwona Buczkowska: To convince the city, we needed to demonstrate that timer housing could indeed easily be built on urban and industrial sites. For the generation that experienced World War II, wood was the symbol of cities of refugees, of slums and other poor provisional structures. We organized a visit to a small wooden housing project by Jaap Bakema which had just been completed outside Rotterdam. Then there was a vote in the municipal council: The older elected officials voted against, the young people in favor of the idea. The mayor considered that he was building for the younger generation, so wood was accepted. It was still necessary to build a prototype of five housing units and to organize an “open day” so that the local inhabitants could visit the interiors and accept them.

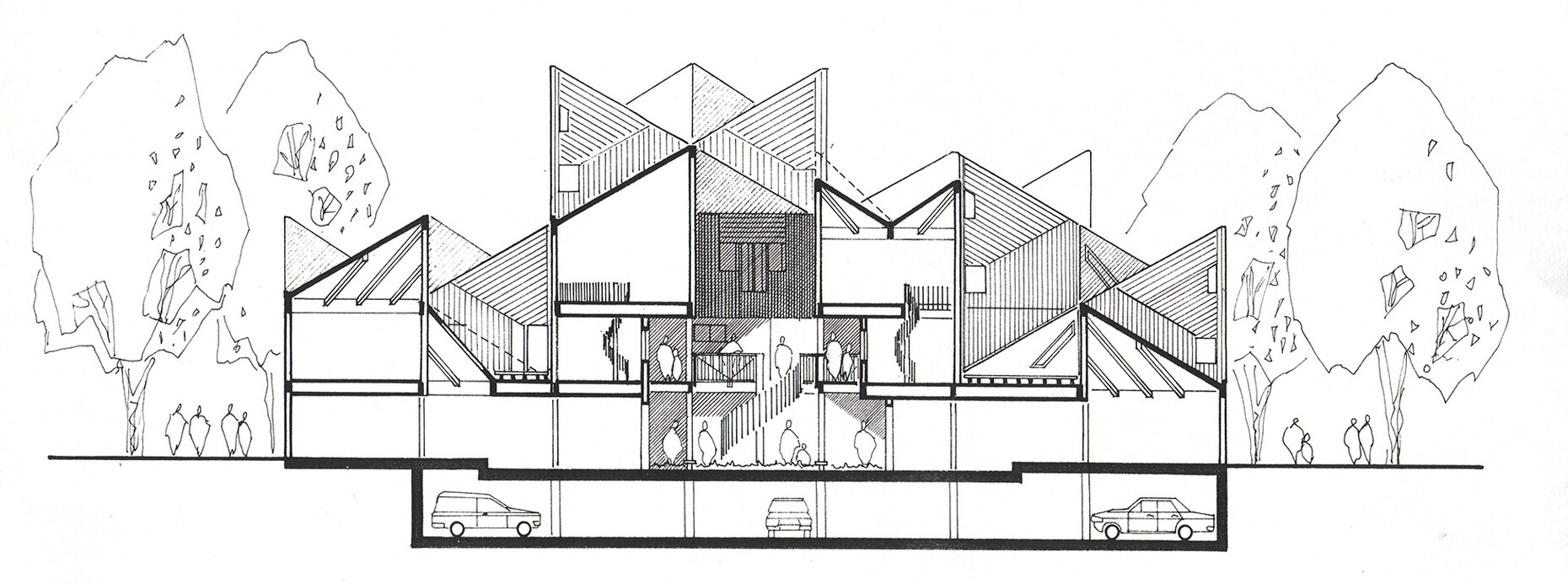

In the end, it took until 1996 – almost 20 years – to complete the project in Le Blanc-Mesnil. While it was still under construction, you won a competition for another social housing project with 96 housing units in Ivry-sur-Seine.

Iwona Buczkowska: Yes. It was a time when there was so much happening with innovative social housing projects in France, especially around Paris. I was lucky to win this competition because then I was able to pay the bills while working for 15 years on Le Blanc-Mesnil.

This project, the Cité Les Longs Sillons, was completed in 1986. It was therefore your first completed project and you moved into one of the apartments. Do you still live there?

Iwona Buczkowska: Yes.

Looking at your overall portfolio, Les Longs Sillons also stands out as one of only very few projects using concrete as its prime material. Why did you choose concrete for it?

Iwona Buczkowska: Out of necessity. In the 1980s, the fire safety regulations demanded to the building be made of concrete due to its height. Today we could have built it with timber by using CLT panels. Originally, we proposed to make the floors and columns of concrete, while the facades and the roofs would have been in wood. But the client rejected the idea. I was very young. Maybe I wasn’t persistent enough.

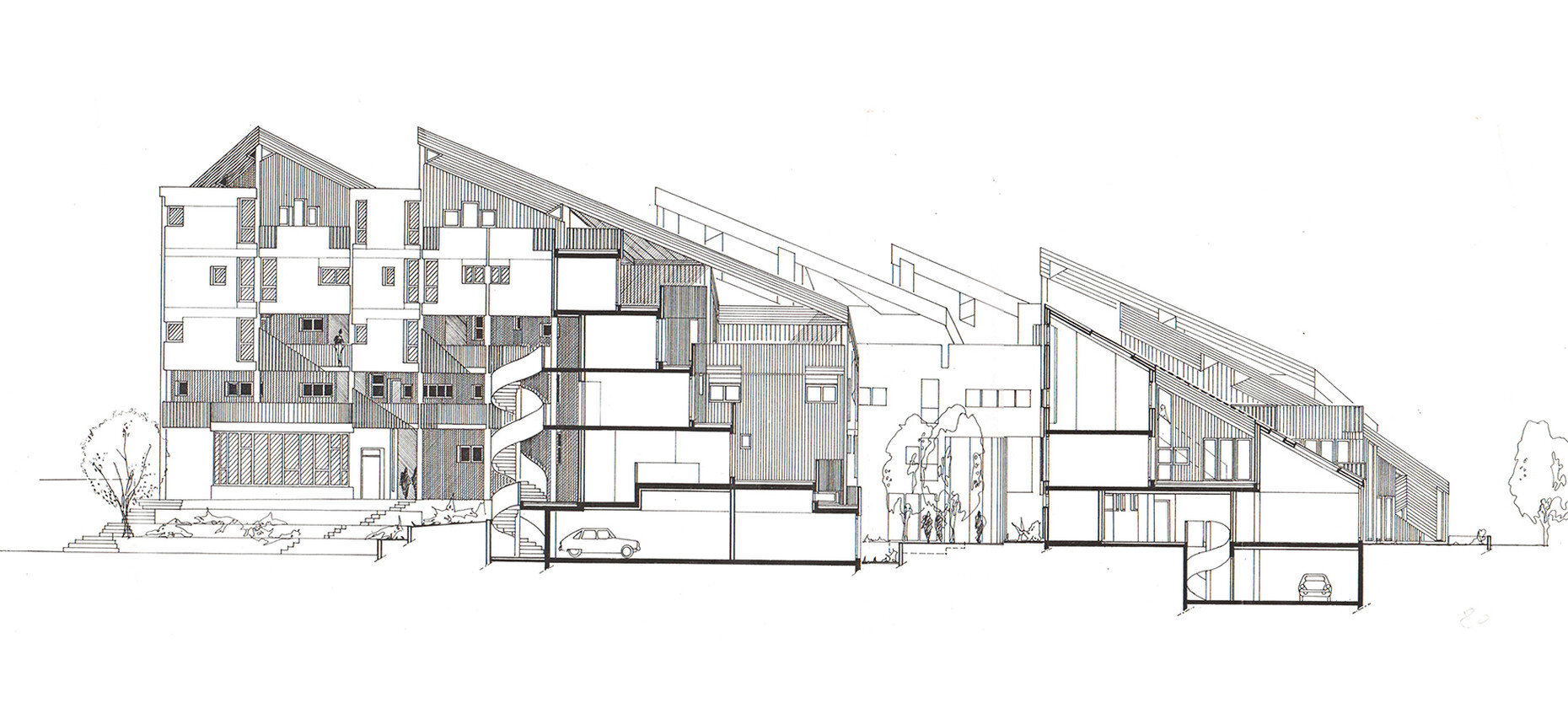

Looking at the many social housing projects in your portfolio, I would be interested in what you see as common features. It looks to me that you are repeatedly using elements like arches and blunt angles, and your preferred materials obviously are wood and fair-faced concrete. What are your main interests in your architecture, what do you try to achieve?

Iwona Buczkowska: All my projects abandon orthogonality, the parallelism of ceiling and floor. Delimited by oblique sections and arches, my projects aim for conviviality and exchange, for light coming from all directions - including overhead. My toolbox includes large cut-outs or panoramic volumes, areas with multiple facades and perspectives, open spaces and floor plans. The neighborhoods I design are always pedestrianized, abundantly planted, and they offer numerous perspectives, passageways, squares and piazzas, gardens and terraces. Wood is often present. In the case of collective housing, the objective is to offer apartments which combine the advantages of collective living with those of individual houses. With offices, it is a question of projecting the circulation areas as large open and well-lit meeting places. In the case of buildings for children, it is about adapting the spaces to their size. For schools, the intention is to design spaces which, through their layout, will facilitate new pedagogies, encourage adolescents to be independent, to exchange and to reflect, and to facilitate learning about democracy.

For me, architecture is not about fashions, not about haircuts. It is about deep reflection on the spaces we believe in and about a living environment we want to create, where humans are at the center of interest. My architecture is about sculpting these places, opening them up to the outside via facades with multiple directions, making their volumes as varied as possible to determine sub-spaces. The objective is to always implement the larges space possible for the future users to conquer. My projects escape repetition and standardization, their spatial and aesthetic expressions are always different, because the context of each of our projects is never the same. Both are the sources of my inspiration. Spaces that breathe, that visually break down distances, perhaps shake up our habits, spaces that inspire us and try to make our cities more friendly and human. According to Bruno Zevi, Architecture is not only an art, it is first and foremost the setting, the stage where our life takes place. I want to create an architecture where you never get bored.

You have concerned yourselfwith social housing for almost 50 years now. What’s your opinion on the current social housing in France or Europe? What has changed down through the years?

Iwona Buczkowska: After May 1968, we all dreamed of living differently. In France there were project owners, politicians, urban planners, architects who all wanted to develop a different vision of collective housing, dissociated from the productivist logic of developers. It was a challenge to the often oppressive image of social housing, which has produced so many urban misfortunes. It was a very interesting period; there were a lot of currents, debates, and interaction. This period ended around the 2000s. Since then I have not built any social housing. All my projects, with the exception of Blanc Mesnil, were competitions that I won. But after 2000, the selection criteria no longer focused on the architectural quality of the proposals. Project budgets are increasingly restricted and research is mainly concerned with thermal problems only.

So what are you currently working on?

Iwona Buczkowska: Just recently I completed the Atelier Gold in Beaumont. I spend a lot of time defending my projects, not only those threatened by demolition like Le Blanc-Mesnil and the Collège Pièrre Semard in Bobigny, two of my most important projects I believe. Due to a lack of maintenance, both are in a poor state, but they can easily be renovated. But also other projects of mine are currently undergoing poorly designed makeovers that are not faithful to my work. The Toit Rouges, the “Red Roofs”, a scheme of 81 social housing units in Saint Dizier, had to be renovated and the local authorities proposed removing the double height spaces and inserting plasterboard horizontal boxes instead. Sometimes I feel that people are so stuck in their preoccupations about what social housing looks like that they can no longer think outside the box.