Inside Out

Florian Heilmeyer: Your book is bursting with energy and inspiration, filled to the brim with your incredibly diverse projects between design, architecture, interior design, art, graphics, and landscaping. Is there a category that really describes what you do?

Petra Blaisse: I don't really like the word "design". I think we do applied work or site-specific interventions. I see us as creators of objects and environments that fulfil specific requests or needs, that respond to the place and the situation. Therefore, we use the media you've mentioned.

The path to your way of working was rather unusual and full of happy coincidences. You started studying art in London and Groningen, but never finished. Have you ever regretted that?

Petra Blaisse: Not really. I like being challenged by the unknown and learning from practice in the "real world".

Instead of continuing your studies, you started working on your own as a freelancer. Did these early loose collaborations already pave your way into how you would later organize your own office?

Petra Blaisse: Yes. I was mostly assisting with photo and video shoots for fashion and other commercial purposes. It certainly helped me to develop my skills in creating environments, using light, colour, materials, objects, and composition as tools. You can manipulate these tools to influence the meaning of the object or person in front of you. As an autodidact I have always been aware of the need to collaborate in order to fulfil my tasks, visions, or goals – whatever they may be – to the standards I have set for myself.

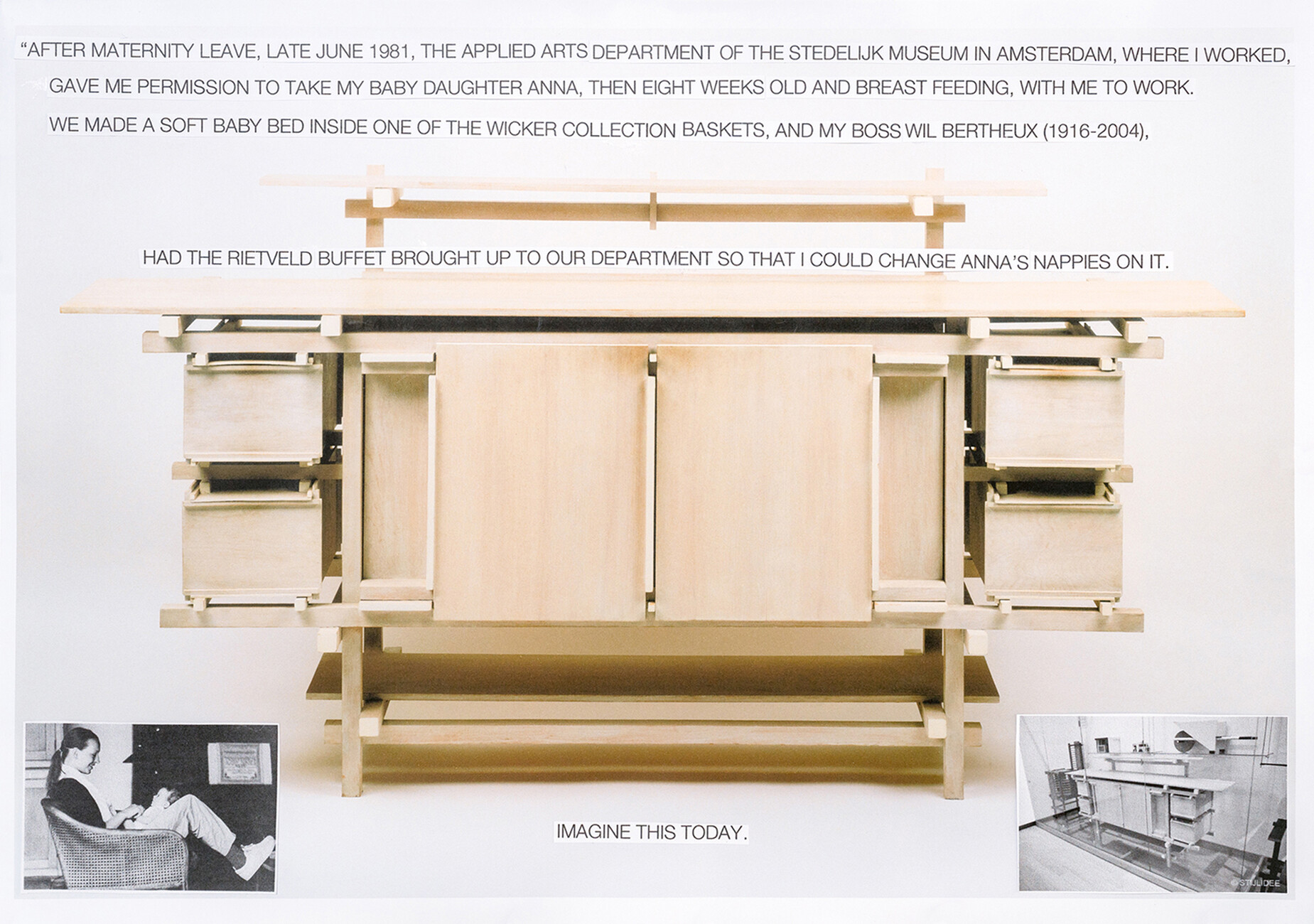

In 1979 you had the fortunate opportunity to work at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, where you stayed for seven years. Were those formative years for you and your later practice?

Petra Blaisse: Definitely. At the Stedelijk I not only did secretarial and archiving work, which was the official part of my job. I also helped the curators with the preparation and installation of all the exhibitions. I learnt a lot, for example to pay attention to all the details of an exhibition. Details such as the short descriptive texts that accompany the exhibited works. Everything matters: font, size, color, the positioning of these texts on the walls and how they were attached to wall or floor – are they printed on paper or cardboard, or directly put on the surfaces? I remember this as a fantastic job, thinking about installations in vitrines, cabinets or exhibition rooms, the influence of the scale and type of objects, their positioning in space, sequence, routing, light condition. The effect of a door opening or window on the composition. My training there was endless, also because of my general interest in modern art, my curiosity about every aspect of it, including storage and hanging systems, restoration works, packaging, transport handling. Plus: All these years, I could freely enter and walk through each space while it was closed to the public, seeing many installations in their pre-state. I remember seeing a compact group of small and medium-size Giacometti sculptures standing close together on a horse blanket; large paintings by Schnabel leaning against the walls with daylight caressing their dark blue velvet patches from a roof window; piles of framed photographs waiting to be selected. Seeing the painting collection in their racks in the cellar’s half-dark, the effect of dust settling on the furniture collection pieces before cleaning, the loss of the glass collection’s glamour when tightly stored in the cabinets…

Another important coincidence was your meeting with Rem Koolhaas in the 1980s – important, I would say, for both of you. This gave you the opportunity to set up your own practice, with your first commissions from Koolhaas' Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA) for the interior design of the Dance Theatre in The Hague, the Villa dall'Ava and exhibitions in Rotterdam, Paris, Barcelona and Basel. It was the beginning of an intense, very productive and successful collaboration that continues to this day. How important would you say this meeting with Rem Koolhaas was for you and your career?

Petra Blaisse: Well, you said it perfectly. I can't speak for Koolhaas, but I would agree that it was important for both of us. But to be clear, I was one of a number of 'satellites' working with Rem and the small OMA team at the time, because there was always an interest in involving people with different talents and professions other than architecture. Writers, sociologists, scientists, and philosophers were invited to comment on a project in the making, and photographers, designers, musicians, inventors, model makers, artists were added to a project team to influence, invent, construct, install, film, exhibit, organise.

In his fabulous contribution to your book, which is basically the transcript of a talk he gave about your office, Koolhaas mentions that "learning" is a key to understanding how Inside Outside works. Do you agree?

Petra Blaisse: Yes. Life is a constant learning process, a never-ending schooling. At OMA it was not a very relaxed way of working, very different from being a civil servant at the Stedelijk! I had to learn how to work, think and create under stress, feeling – and sometimes suffering – the constant competition with other creative minds. So you learn how to go through situations without feeling personally addressed, to be open to other people's strong convictions and directions, but at the same time to trust your own thoughts and instincts. For me, as a control freak and therefore afraid of making mistakes or losing control, it was important to learn to use these contradictory and "threatening" energies in a constructive way. A sense of humour, improvisation, interest in the 'other' and diplomatic interaction are important tools that I have come to appreciate more and more in the practice of my profession.

Were there other acquaintances or happy coincidences of equal importance?

Petra Blaisse: Many of them. My mother, a potter and painter, passed on her eye for art and composition in all forms and her love of the outdoors; my father, his ambition and perseverance. My first husband Tom, a historian, inspired my love of photography, poetry and jazz music; my boss at the Stedelijk Museum, architect Wil Bertheux, taught me the importance of scale and space and how to appreciate and recognise good design; Lily ter Kuile, ceramist and gardener, was an important teacher in the field of natural gardening; Hans Werlemann, photographer, influenced my understanding of how to go about a creative process; by testing and trying until it is right; by asking questions and working together. Dutch artist friends like Fred Bosschaert and Berend Strik made me appreciate ugliness and tastelessness as essential ingredients of beauty; girlfriends old and new remain inspirations and examples through their talent to combine work and private life with acrobatic talent, courage, curiosity, never-ending energy and loyalty; and then, most importantly, our children hold up healthy mirrors with their need for unconditional love, while challenging us with their confrontations and quests... often triggering the need for thorough inner reflection.

You currently work with a small team of eleven people in the office and three partners, namely yourself, Jana Crepon and Aura Luz Melis. How do you divide the work between the three of you?

Petra Blaisse: Jana is a landscape architect and Aura is an architect. They are passionate colleagues who have worked with me for many years. They became partners in 2016 and will soon be equal partners. We each have our own projects, yet we manage the studio and acquire commissions together. My role is to be always involved in the conceptual phases, the creative aspects and the financial and diplomatic side of our work. My role is also to take the work of our studio out into the world, hence the book.

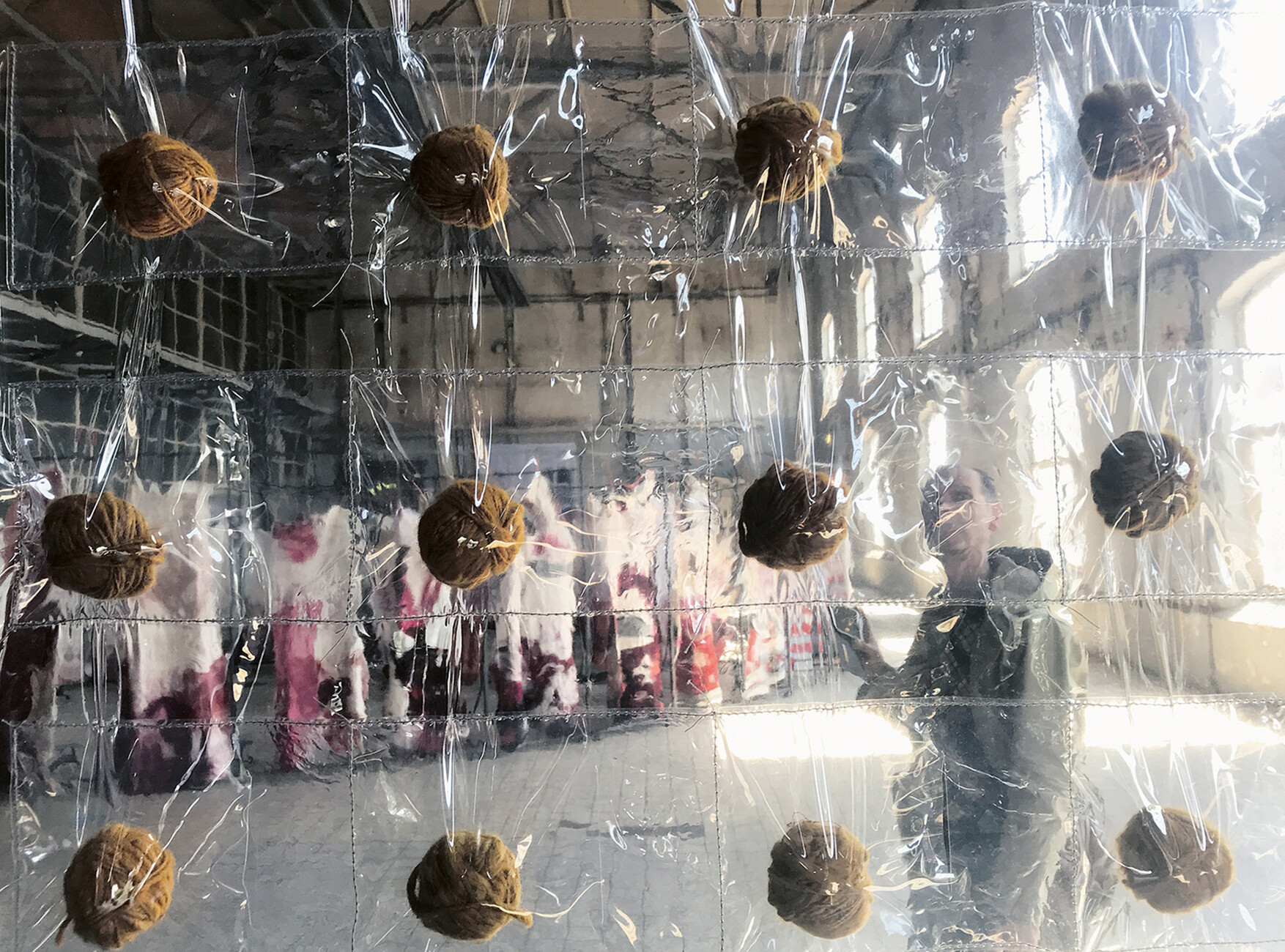

You seem to have always been interested in different textile techniques from all eras. Is there a particular technique or craft that you are currently working on?

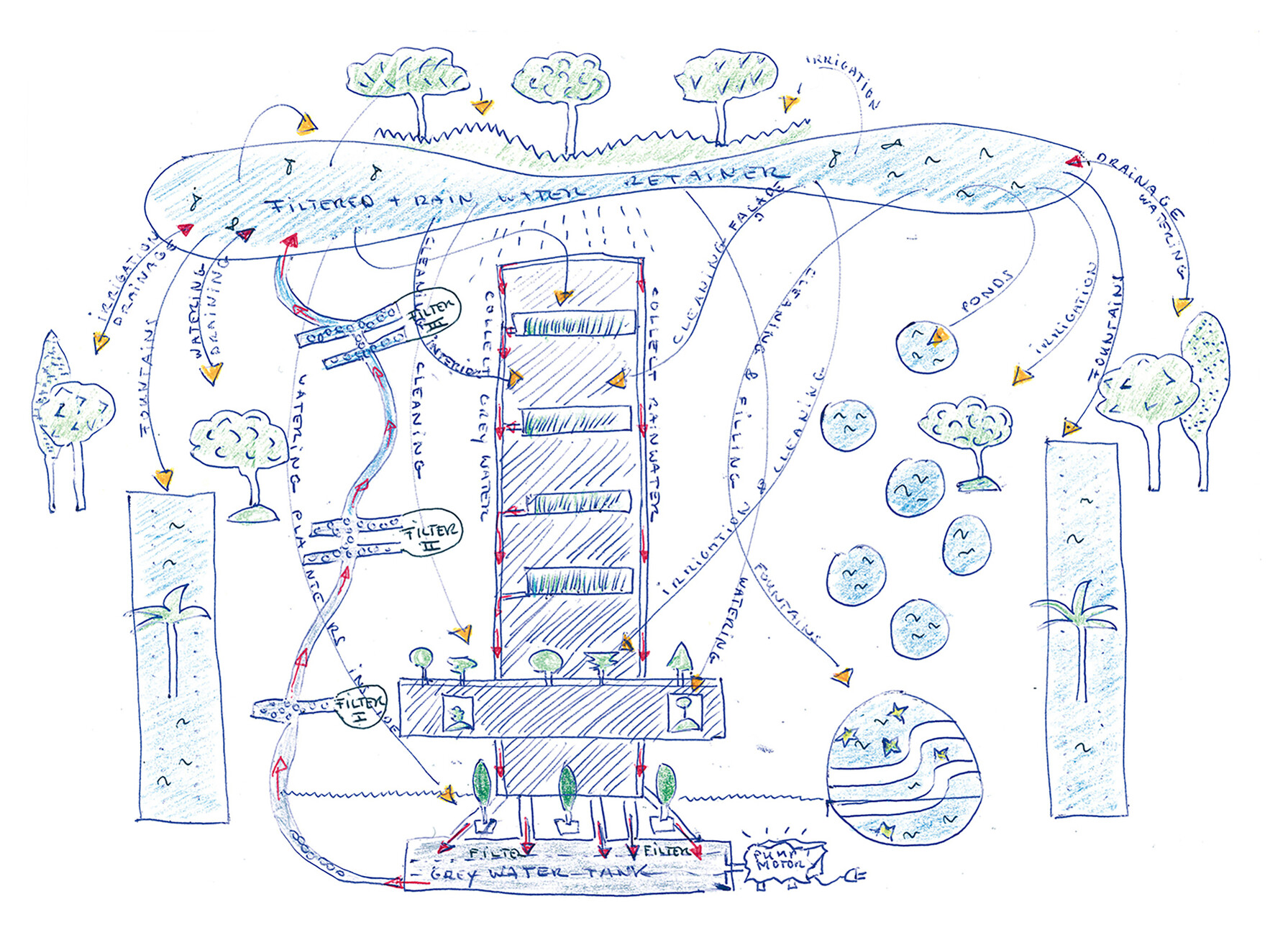

Petra Blaisse: In collaboration with the Textile Museum in Tilburg, the Netherlands, we are currently exploring the possibility of developing a textile base – knitted, braided, or woven – on which nature, such as mosses, spores, seeds, fungi, can settle. This could be on a temporary canvas, such as a scaffolding net, but the aim is of course to create a substrate that absorbs moisture, nutrients, and green life, but does not decay, and at the same time can make all the elegant movements of a curtain – expanding, contracting, and billowing in the wind!

In addition, we will be revisiting our old goal of developing large-scale exterior and interior curtains with integrated solar cells, so that the shading and acoustic qualities of our curtains in front of the large glass surfaces of the public buildings we work with can fulfil the additional role of energy provider.

On your website you say that Inside Outside "works internationally on projects of increasing technical sophistication, ambition and scale". Could you elaborate on this increasing technical sophistication?

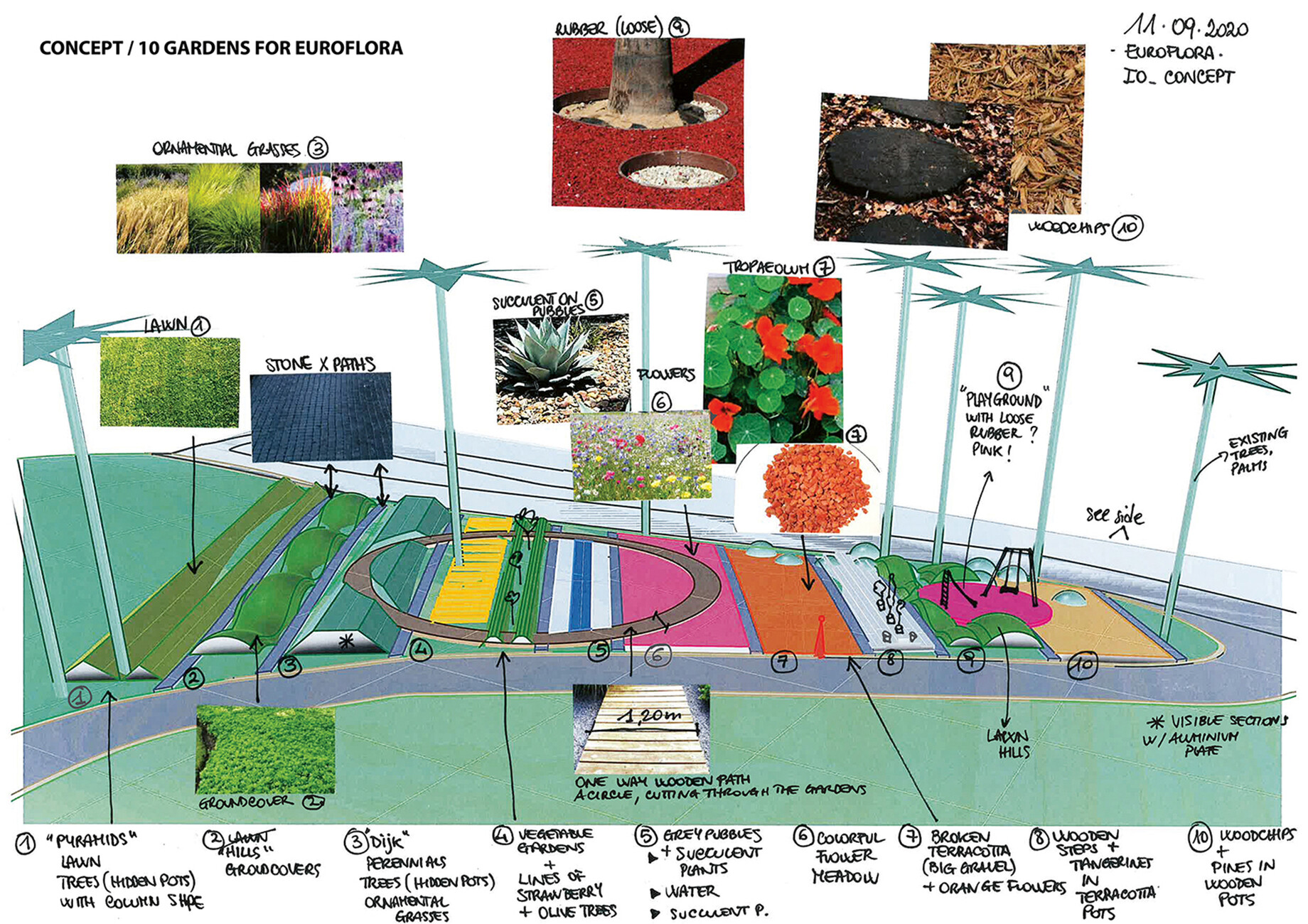

Petra Blaisse: We still see ourselves as a creative studio of curious minds with a hands-on mentality and a lot of idealism – in the sense of wanting to bring beauty to the world, to contribute to its health, liveliness and yes, even happiness. All of this must be combined with functionality and intelligent technical solutions, otherwise we would become "too soft". It is therefore important to have the right knowledge and understanding of the issues and situations at hand. However, the creative side remains the main objective and we spend a lot of time trying to find the right balance between beauty, originality and function.

How many projects are you currently working on? And do you have a favourite one?

Petra Blaisse: We're working on about twenty projects, all at different stages. Favourites depend on your point of view. Some projects are fun because of their relative simplicity - which is deceptive – or the short timeframe. Others are fascinating because of their complexity and the time they take. Some are rewarding because they have a social or environmental purpose. Some are exciting because we can connect with professionals or scientists outside our own field to gain collective knowledge on a topic.