YOUNG TALENTS

Designing as a Method

Elisabeth Bohnet: Your places of education have strongly influenced your work. What is your educational background?

Johanna Seelemann: I started studying interior design at Burg Giebichenstein and then switched to industrial design. Towards the end of my studies, I went on an exchange to Iceland, packed with lots of skills. I always knew that I wanted to work in a contextual and systemic direction, but I didn't know how to apply my capabilities. Iceland really helped me to orientate myself. I understood the system of raw materials there. I liked it so much, the team of tutors was stimulation and the dynamics of the degree programme were very different, so I changed universities and stayed there until I graduated in 2016. I then moved to the Netherlands and completed my Master's degree in Contextual Design in Eindhoven in 2019. Ever since my studies, I enjoyed collaborating with colleagues and worked for example at Formafantasma's studio. Today I run my own design studio but still work in many collaborations.

How does the study programme differ in Germany, Iceland and the Netherlands?

Johanna Seelemann: During our studies in Germany, we learnt the basics with a strong focus on industry, which certainly stems from the fact that we have a well-developed infrastructure. The entire design philosophy and the understanding of what design is differs greatly from the Netherlands and Iceland. In the Netherlands, it is anchored in the definition that design is a tool for debating and researching, for engaging with society and thinking about where it should go. In Iceland, on the other hand, there is hardly any industry that can be designed for. That's why the dominant way of thinking in design there is to deal with local materials, with the local context. But it's also very much about the zeitgeist and experimenting with new technologies. There is an open attitude, a great willingness to experiment. The teaching in Iceland was characterised by the training in Eindhoven. The culture there has grown much longer for these types of design research, critical design, social design and contextual design.

Did you previously have a connection to Holland or the northern European countries?

Johanna Seelemann: No. I went there on a recommendation without expecting anything and was then completely taken by surprise in a good way. In Germany, there are many structures that have grown over a very long time and are very mature. As soon as you start looking for material in Iceland, you just have to go or know someone who knows someone. There is not much mature craftsmanship in that sense, but perhaps a company that casts aluminium and relatively much in the field of wool processing. After that, there's not much more. So you build your own tools. For me, it was very helpful to come into this context and experience a lack of infrastructure that I was used to before. That automatically led me to certain methods.

How do you approach a new project?

Johanna Seelemann: I usually start with theoretical research or a certain idea that drives me. After that, it depends on the narrative material. For my final project in Eindhoven, "Terra Incognita", I focussed on the German automotive industry. It started with a curiosity about this branch of industry with the car as Germany's most important export product. In the history of automotive design, people started styling cars in the 1920s and 30s. Inspired by fashion stylists, manufacturers copied strategies in order to sell new models. Before that, design was primarily functional. I was absolutely fascinated by the theme of aesthetic innovation and evolution. The core material for aesthetic design, industrial clay, is still used today to mould prototypes by hand. This brought me to the subject of adaptability or the possibility of transformation, and to the idea: what if there were objects that could simply be adapted to any style, that could always be reshaped? Certain thoughts are developing that I am carrying forward into the next project.

For your "Oasis" project (2023), you made terracotta containers to water urban trees that are embedded in the ground. Can you explain the idea and the technology behind it?

Johanna Seelemann: The MAKK Museum in Cologne invited me develop a project on the occasion of the exhibition "Between the Trees". While I already encountered the subject of timber production in previous projects, trees in the city take a special role, they are not part of the forest or timber production context. Research into the stress factors of urban trees revealed that clean water is the key factor for their health. This made it clear to me that I wanted to focus on irrigation. The "Oasis" objects are based on a historical watering technique that has been around for thousands of years and was used in ancient Greece, for example. Clay pots are buried and filled next to the trees, which gradually release the water to the tree. In this way, the water neither evaporates nor seeps away and is thus available to the tree. So the idea is old: I have taken the archetype and transferred it formally into a contemporary, technical language. The shapes look like fuel tanks and thus also tell of the urban competition between trees and cars. We made the clay pots in a small ceramics studio and will be exhibiting them at the Milan Furniture Fair. In the "Micrographia – Redesign for Biodiversity" exhibition, we will be showing two versions: Low-fired, it serves as an irrigation system and high-fired, as a simple vase. This is where duality comes into play: design intended for the plant, but also useful for people. And although it can be used practically, in the end it's also about the gesture.We currently have a small handmade collection.But I would like to scale up the project and make it marketable with an industrial partner.

The new is often not so new, or to put it provocatively: is it still possible to design something new?

Johanna Seelemann: The more research I do, the more I believe that a lot of things have already been done. There is definitely a lot of knowledge that we can draw on. At the moment, design is more about the relationships to materials and forms of production or to certain standardisation rules that we have created for ourselves. For example, we produce scrap materials that are actually unnecessary if you think about a different aesthetic perception, such as light-coloured areas in the wood or knotholes. This also has to do with the expectations we have of quality. I can see this clearly in a project I am currently working on in the Ore Mountains with the woodturning co-operative in Seiffen. We were there with a collective of designers and talked to numerous craftspeople. The co-operative is struggling with a lack of young talent. In the next ten years, fifty per cent of the artisans will retire without a successor. In addition, a paradox became apparent: they try to make every product look exactly the same – even though the items are handmade and hand-painted. They want to reproduce an industry standard with their craftsmanship. We asked ourselves the question: What actually characterises a handmade product? What is the uniqueness of the craft itself?

Which material surprised you the most?

Johanna Seelemann: There were definitely a few surprises at the beginning of my exploration of clay, and what is possible with such a simple material: how capable clay can become in combination with other materials such as straw or dung, sometimes even waterproof; and that this simple material can be used again and again when dissolved with water; it is also a material that is used in completely different ways across all cultures worldwide. We took part in workshops at the European Clay Building Centre in Wangelin. I learnt a lot in this test territory, from earth building to earth art and rammed earth. The whole site is full of test walls and test houses – super fascinating.

You say that people have aesthetic expectations of a material and, above all, of sustainable design. What do these expectations look like?

Johanna Seelemann: A few years ago, a kind of eco style association dominated in relation to sustainable design, which is currently changing dramatically. Anyways, I recently spoke to Henriette Waal, who co-founded the LUMA studio. They put up a rammed earth wall in the south of France and mixed in lime, which turned the clay grey and made it look like concrete. The clay builders were very disappointed because they thought it no longer looked as natural as it actually is. I do believe that the perception of clay is still in an eco-corner; a round, soft, primal aesthetic is expected. Of course, there are also counter-examples such as Martin Rauch, who produces earthen wall elements in Austria and uses the material in a different way.

The aesthetic expectation and the assumed truth are often not confirmed if one looks at things for longer. You have focussed on fire in domestic use.

Johanna Seelemann: For the Vienna Design Week, I was brought together with a local manufacturer, a stove builder, in the "Passionswege" format. That was extremely interesting because I was confronted with all my prejudices about stoves in terms of sustainability and burning wood. The Low-tech Magazine was one of the things that was relevant to me when I started looking at the topic of fire. I learnt that fire was historically used very differently to how we perceive it today. Today, domestic fires are mostly used decoratively to create a cosy atmosphere. But historically, the one fire in the household was used for all sorts of things, from cooking and heating to drying laundry and conserving food. They also cared about how to maintain a fire effectively. There were also different techniques for wood sources. Around a hundred years ago, probably forty per cent of the forests in Europe were coppice woods. The branches of fast-growing trees were harvested, not the entire tree felled, which in turn could grow new shoots more quickly. Of course, it is questionable whether this would even be possible on the scale we need today. But it still shows a different method of dealing with the raw material. These insights actually led to changing my perspective. And again: old knowledge! What did we actually know before and what have we forgotten? As we have reached a certain level of comfort, we are no longer dependent on certain knowledge, but this also means that a lot of valuable knowledge gets lost. The object that the stove builder and I then made was a stove in which we tried to change the way it works. Entire logs can be pushed into it, and the heat is regulated by how far the wood is pushed in – and you can cook on it.

You worked with glass in 2018 and again in 2023. What is the idea behind "Vitrum"?

Johanna Seelemann: We wanted to explore recycled glass and were particularly interested in the expressive power of glass. The project revolves around the questions: When do we become attached to products? Is it perhaps the uniqueness of an object? How can you produce objects in series that are still unique pieces? We wanted to use air inclusions to produce unique pieces. It was exciting to work with the glassblower, for him it was of course very unusual to provoke uncontrolled air inclusions in an object. The opposite is normally the standard. We allowed a lot of air – and produced quite successful objects.

What are you currently working on?

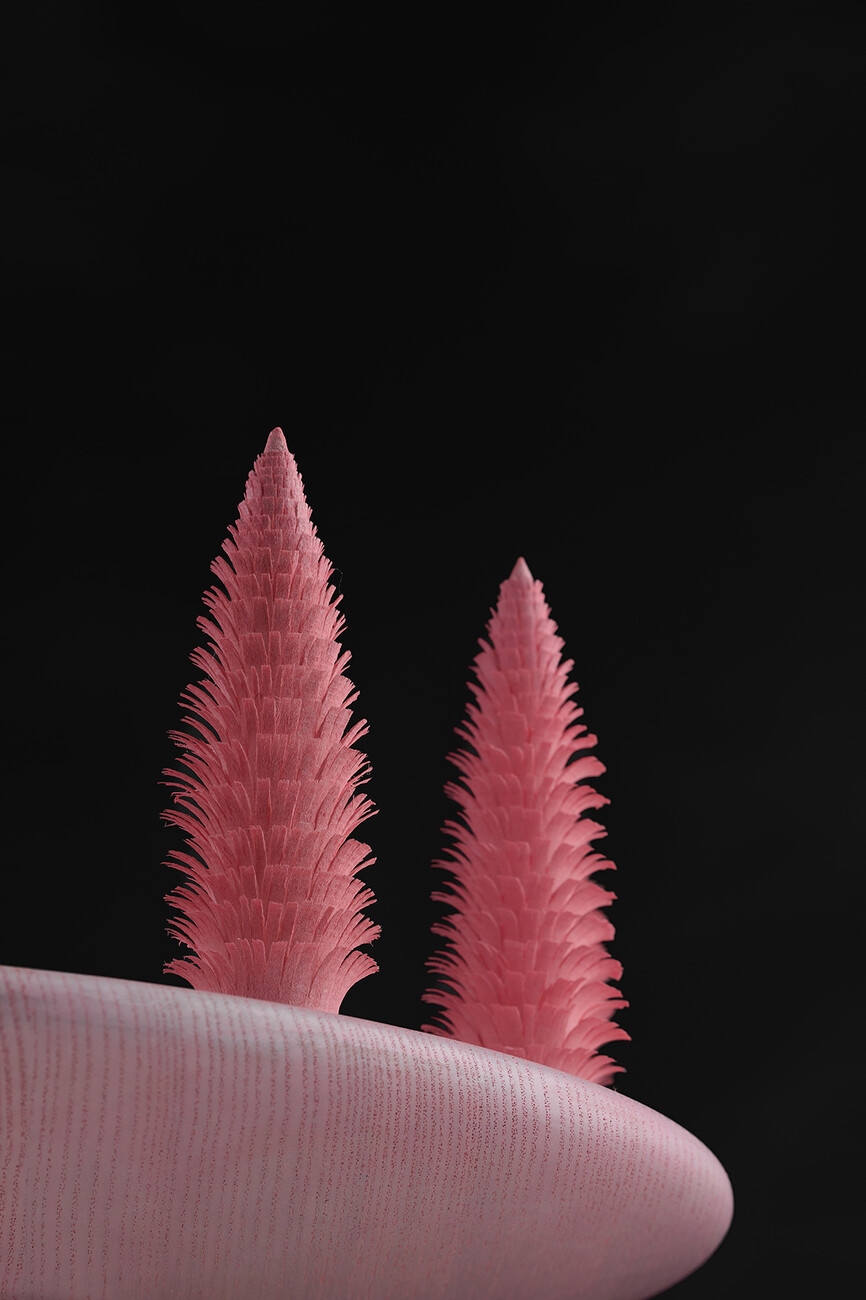

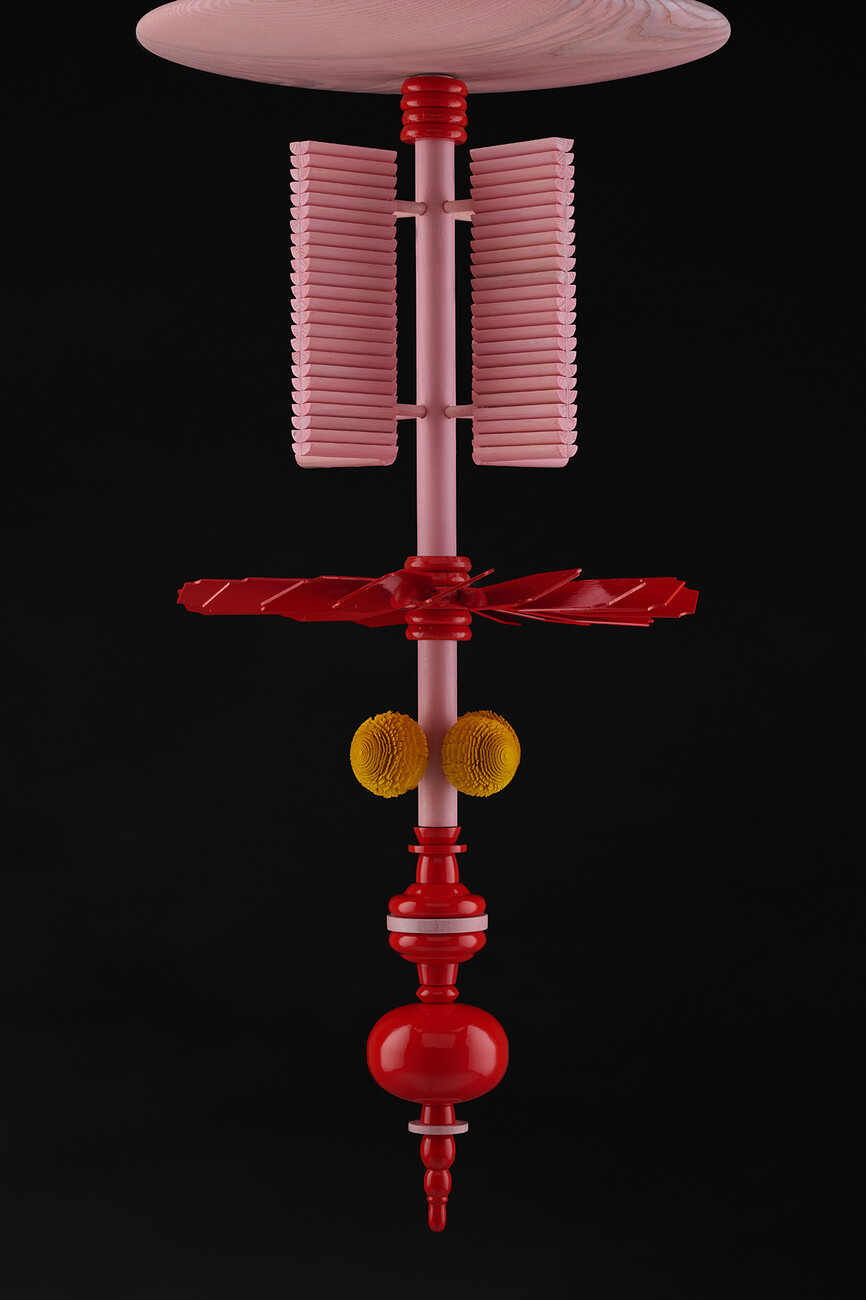

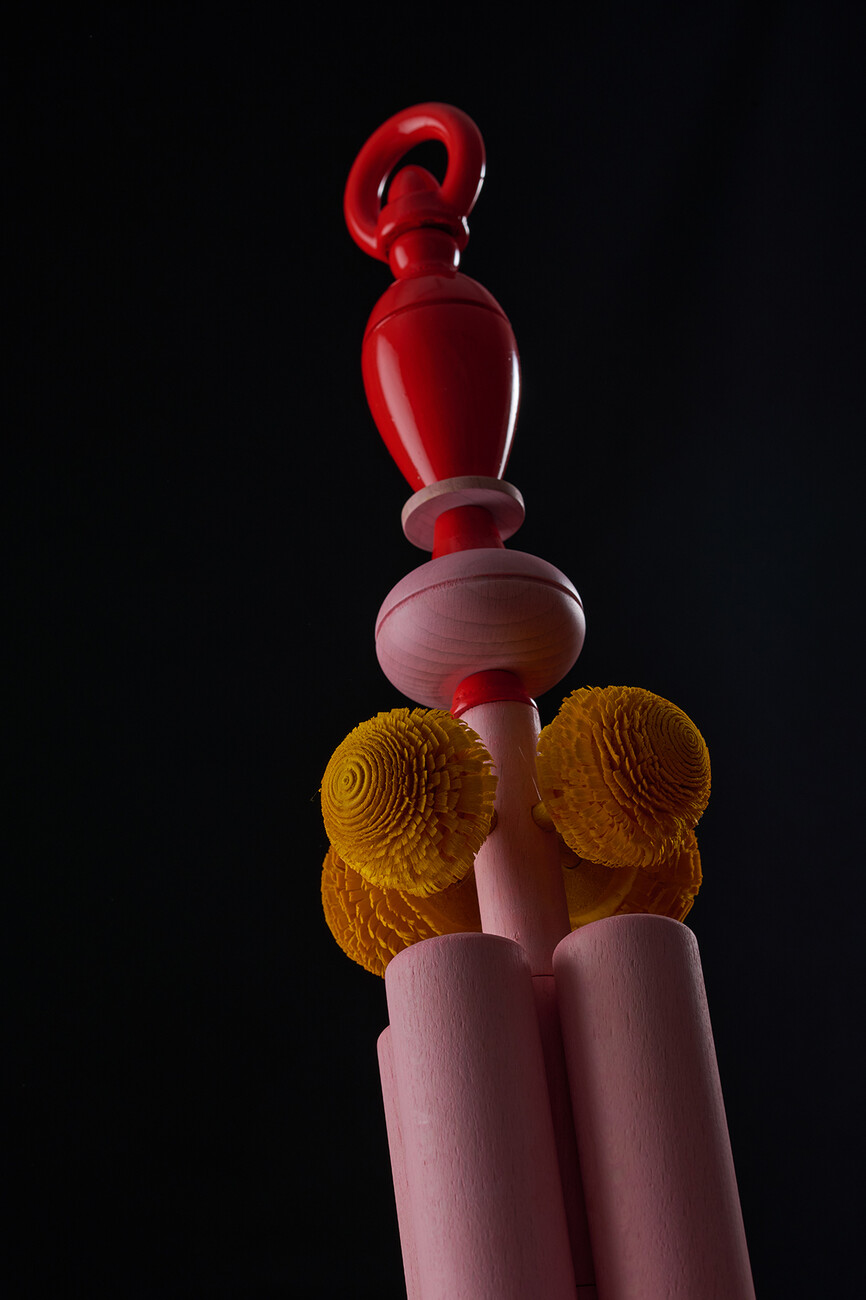

Johanna Seelemann: We are currently developing an object that will soon be shown in the "Wood Land" exhibition curated by Alice Stori Liechtenstein at Schloss Hollenegg for Design. The project with the woodturning co-operative gave rise to the idea of making a "Leuchterspinne" ("chandelier spider") together. Due to the history of mining, the Erzgebirge had a special relationship with light. In the 18th century, these chandelier spiders were created in an attempt to reproduce chandeliers or chandeliers with the means available, using wood. This gave rise to a separate object category that hardly exists today. Only a few people still produce them, and then in a simplified form, often for the Christmas context. Originally, the pendant lights were very complex; they were made for weddings, for example, or for special events. The design language was partly naïve, partly crazy, but really beautiful and very fascinating. We wanted to transfer the shapes into non-Christmas object typologies in order to reach a different market than the classic market for traditional wooden objects from the Erzgebirge. That's why we made a lamp that is very playful and looks more like a space station, but is still reminiscent of this Leuchterspinne. It's about translating traditional technology into new object typologies.

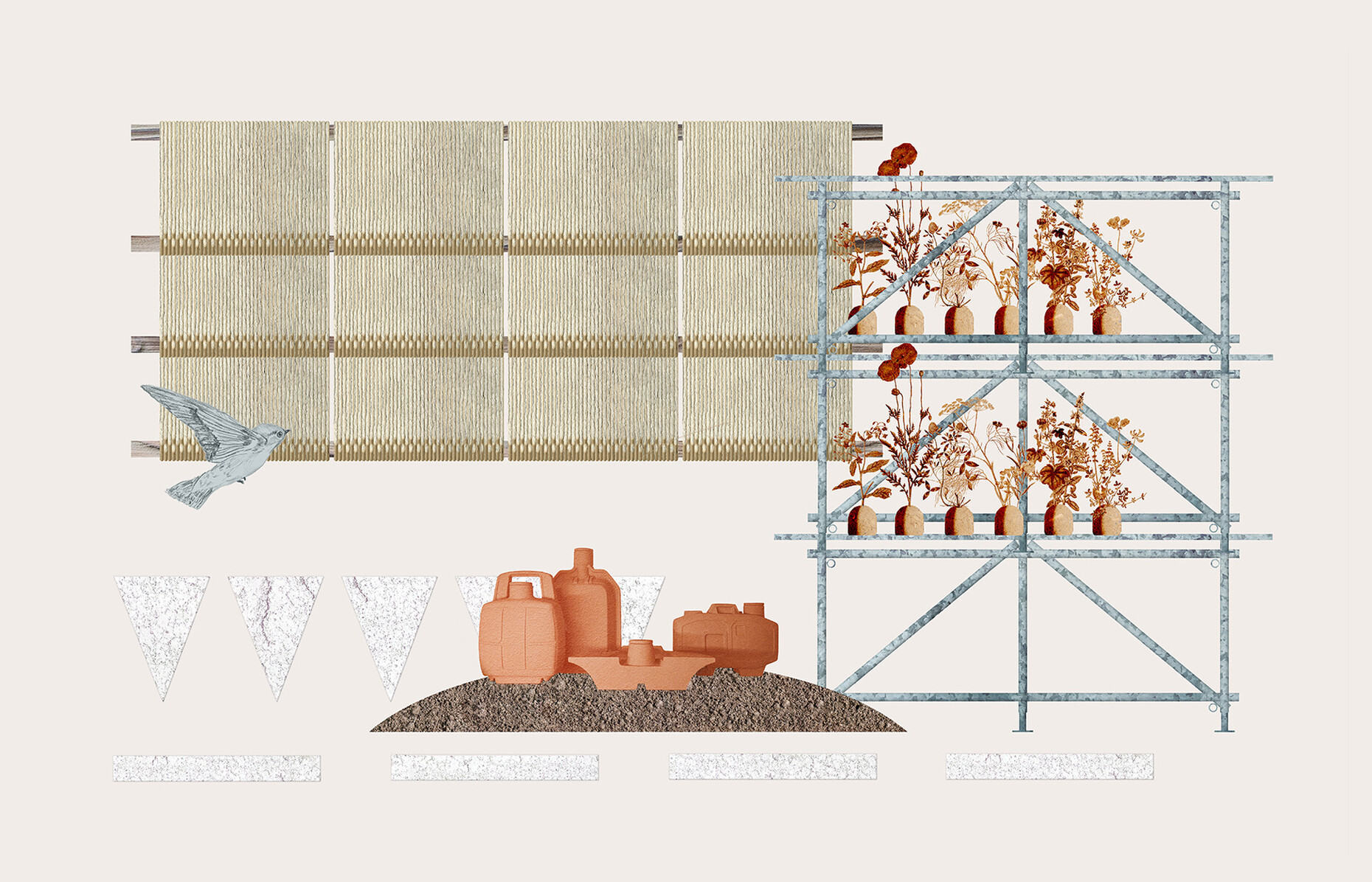

Johanna Seelemann: Milan is also just around the corner: I mentioned the "Micrographia" exhibition project, the title of which is based on Robert Hooke's book from 1665 and which I am developing with the support of architecture firm Park Associati. He was the first to depict enlarged cells of plants, but also insects, such as the frontal view of a fly, extremely enlarged. The idea in Milan is to continue my Habitat concept: How can we design urban spaces or create products in such a way that they can also be used by other living creatures? We are showing three projects: One is "Oasis", as a water reservoir and as a vase. Then there is a façade element that we are 3D printing together with Ricehouse and Arch3D using newly developed a geopolymer. This façade element is like a normal curtain-type, back-cooled façade, but insects and birds can also move in. We are also working with Primat, a company from Lombardy that specialises in historical plasters, to produce a seed bomb in the form of a panettone with local clay and indigenous seeds from the Milan area. The exhibition returns to the question: How do we design our cities? And are cities only designed with people in mind, or in what way can we take other forms of life into account and provide them with living space? Cities are currently gaining in importance in terms of biodiversity. There are still many areas to be discovered and developed together with industry.

Micrographia – Redesign for Biodiversity @ Milan Design Week

Park Associati Hub

Via Benvenuto Garofalo 31

20133 Milan

16 – 21 April 2024: 12 pm – 7 pm

Opening: 16 April: 7 pm – 10 pm

Wood Land

Schloss Hollenegg for Design

Hollenegg 1

8530 Bad Schwanberg, Austria

4 – 31 May 2024