Unorthodox architecture

"Unorthodox" is the name of a mini-series on Netflix about a young woman named Esty who breaks free from her ultra-Orthodox religious community plus forced marriage. She secretly escapes from her cramped flat in New York and travels to her lesbian mother, who has lived in Berlin for a long time. You don't really need to have seen the series, the story is told in three sentences. But the way the film uses architecture to stage Berlin (once again) as a place of freedom is very remarkable. While Williamsburg in New York is shot almost exclusively in interior views, with small, mostly curtained windows, Berlin is one bright, wide-open ray of sunshine: arrival at Tegel airport, lots of glass and sky, then in a taxi through Tiergarten, lots of greenery and even more sky, and already Esty is standing at Winterfeldtplatz, first looking at the piece of paper with her mother's address, then looking up in disbelief. The house in front of her is ... is ... obviously quite different from anything she knows: wonderfully playful and ornate, it stretches towards the sky like a tulip blossom – each balcony like a twisted leaf, the whole house as if frozen in growth just before flowering. What has been chosen here as an architectural symbol of an elated, liberated life is the "Wohnhaus am Winterfeldtplatz", designed by Hinrich Baller with his second wife Doris, built until 1999. Together with Scharoun's Philharmonie and the Strandbad Wannsee, it plays the main architectural role in the mini-series as an overall image of an elated, liberated city and society.

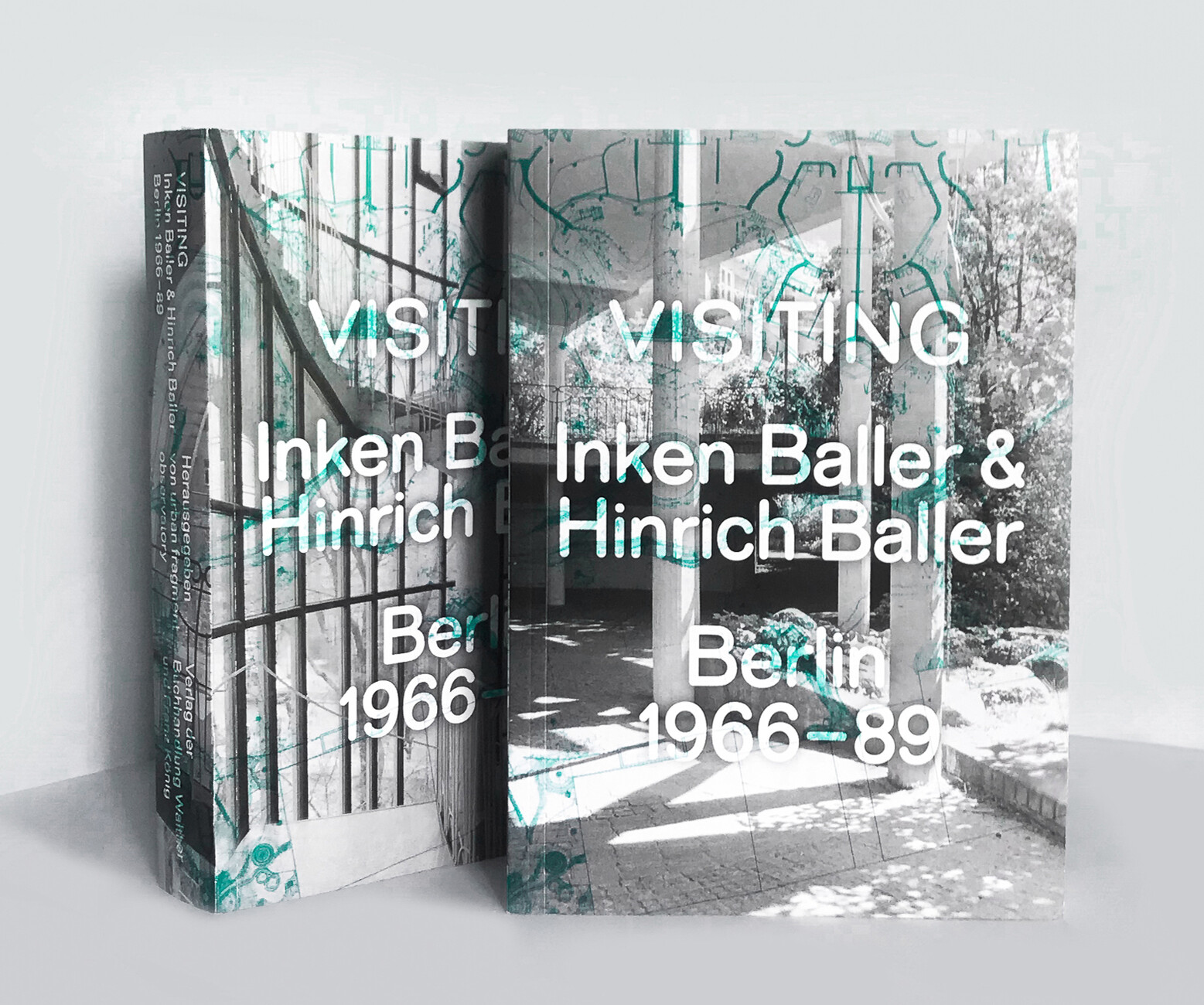

"Unorthodox" would certainly also be a good choice if one were looking for just one word to describe the Ballers' architecture. "The Ballers" means a total of three architects, because before Hinrich Baller married Doris Piroth in 1995, with whom he still designs together, he had worked with his first wife Inken Baller for almost 25 years. A book is dedicated to this first working relationship, which has now been published almost simultaneously with the Netflix series: "Visiting. Inken Baller & Hinrich Baller 1966-1989".

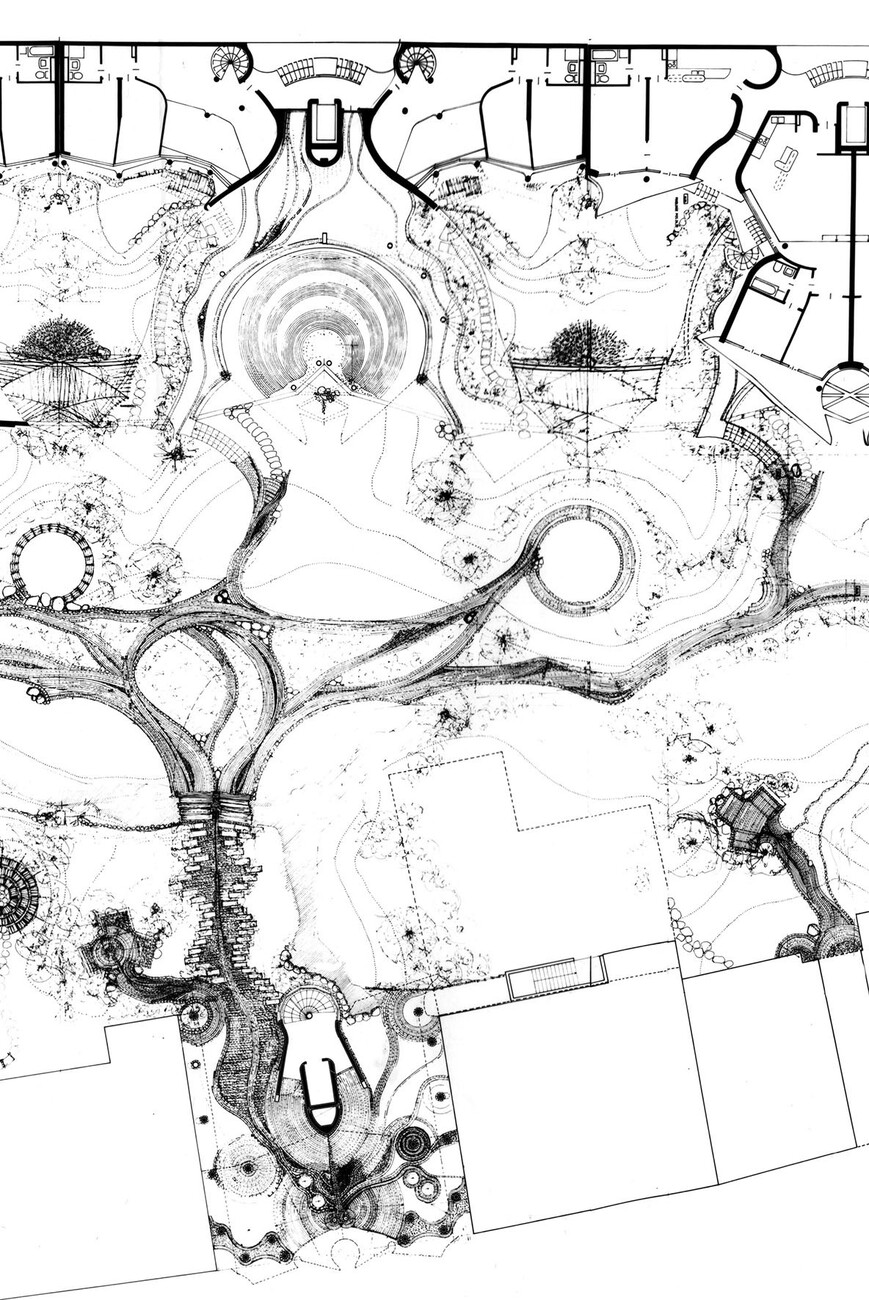

When a film and a book discover something almost simultaneously, it has meaning. Here, it is above all the strange silence that reigned around the Baller buildings all these years. Of course, the buildings were well known in West Berlin. They were, after all, almost everywhere and they always had a striking verve: the "Baller-Bauten" on Fränkelufer in Kreuzberg, for example, right next to the Admiralsbrücke on the Landwehrkanal, with which Inken and Hinrich closed the war-ravaged building block on the one hand, but at the same time turned it into an inner-city and publicly accessible oasis with wide-open entrance facilities and an intensively landscaped, huge inner courtyard. Or the "Baller-Haus" on Potsdamer Strasse, a corner building whose first two storeys are set back behind freestanding round columns, creating a kind of commercial colonnade, but which, because of the bent columns and the curved concrete roof above it, looks more like a small forest than a standard colonnade. Or the apartment buildings on Lietzenburger Strasse in Charlottenburg, not far from Kurfürstendamm, where the prefabricated concrete elements of the balconies are broadly curved like lily pads. Here, too, there is a grove of columns in front of the first two floors, but the first floor is left completely open as a city balcony in the middle - a sweeping spiral staircase leads up from the pavement here. The book shows that the Ballers, with their office community, were very stylistically confident in their very own way of developing residential buildings right from the start.

But little was written about them, and the Ballers did not find much resonance in discourse either before or after 1989. Not only were their buildings scattered all over the city - Inken and Hinrich had already built a good 60 houses together – but they were also particularly striking in the way they refused to stand neatly in a row next to all the angular tenement buildings. The Baller buildings literally danced out of line, took up the straight lines of their neighbours and formed cheerful curves out of them, because now one didn't have to take everything so seriously. In addition to the curves and the ornamented, pastel-coloured balcony railings of this architecture, there was also a double transparency of their houses, because the twists and turns of the buildings are not an end in themselves: through them, the living spaces with often astonishingly large windows turn towards the daylight and at the same time remain protected from the view from outside. In addition, however, there is the very liberal permeability of these houses, which formulate fluid boundaries between inside and outside, between private and public space. For example, many of their buildings offer covered zones or attractive entrances to green courtyards that are also open to curious passers-by. In the case of the Baller buildings on Fränkelufer, this open-heartedness has meanwhile led to the inviting passages to the green courtyard almost always being blocked by metal gates because the residents complained about all too many people using the bushes to pee and dump rubbish. However, this does not change the fact that it is still a good idea to formulate urban architecture in a fundamentally open way – it can still be blocked off.

Houses to live in

So it was high time to put all these projects in a row - and the book "Visiting" impresses overall with the unagitated way in which it approaches this project. 26 buildings are sorted in chronological order and each is introduced with a site plan and a concise, factual description. This is followed by photos and plans in which the reader wanders through the buildings. In the photos, the historical level mixes with the present-day level, as the editorial collective ufoufo – four young Berlin architecture graduates – visited all these buildings and photographed them inside and out in their present-day condition. This is wonderful because it shows the exteriors in their robust overgrowth and the interiors as used, inhabited, living spaces. In this way, it becomes clear without too many words how wonderfully the Ballers have created unorthodox living space that is absolutely fit for the life of its inhabitants to spread out in it. This is all the more impressive because most of the buildings were realised under the strict specifications of West Berlin's social housing programmes – housing programmes whose dutiful application at the same time gave rise to monotonous housing estates such as the Märkisches Viertel, the Thermometersiedlung or Gropiusstadt.

In addition, "Visiting" includes a few transcripts of conversations with the residents of some of the houses, as well as an interview with Inken and Hinrich Baller at the beginning. They talk not only about the conditions under which the buildings were built and the strict requirements of social housing in West Berlin, but also about the precise and loving composition that lies behind the playful, overgrown appearance of this architecture. Hinrich Baller: "When I come out of the narrow stairwell through the door into the flat, everything is directed outwards, becomes larger. One is constantly confronted with enlargement. The windows are the very biggest thing and outside comes the landscape, the trees. This breath, that is very decisive. Also how the doors are placed, the views, that creates a dramaturgy ... we always made the balconies as big as possible." And unlike the usual post-war flats, in which a clear hierarchy from the living room to the parents' room to the children's room is set in concrete, an equivalence of rooms was important to the Ballers: "We always tried to ensure that this required parents' bedroom could be accommodated in as many rooms as possible in our flats ... that the rooms are relatively equal in value and that there are possibilities for connection, thus giving us flowing rooms." This is what lies behind the flowing lightness of these buildings, and it is not for nothing that one is reminded of the organic architecture of a Hans Scharoun or the expressionism of a Hugo Häring – just two of the influences that have been melted and forged into a new, unusual whole at the Ballers.

It is a pity that this consortium of Inken and Hinrich Baller did not survive the divorce in 1995. It is also a pity that their work has remained on the small scale of housing construction and that, despite their participation in competitions, they have never been entrusted with a larger task. Especially after leafing through this book closely, one would be very curious to see what an entire city district would look like. Speculatively speaking, what would have happened to Berlin if the Ballers had designed Potsdamer Platz, the Spreebogen or at least the Chancellery? Maybe they would have made the conditions there dance the way they did in the social housing buildings in West Berlin between 1966 and 1989.

urban fragment observatory (ed.)

Visiting: Inken Baller & Hinrich Baller. Berlin 1966-89

Publishing house of the bookshop Walther König

Berlin 2022

544 pages

39,80 Euro