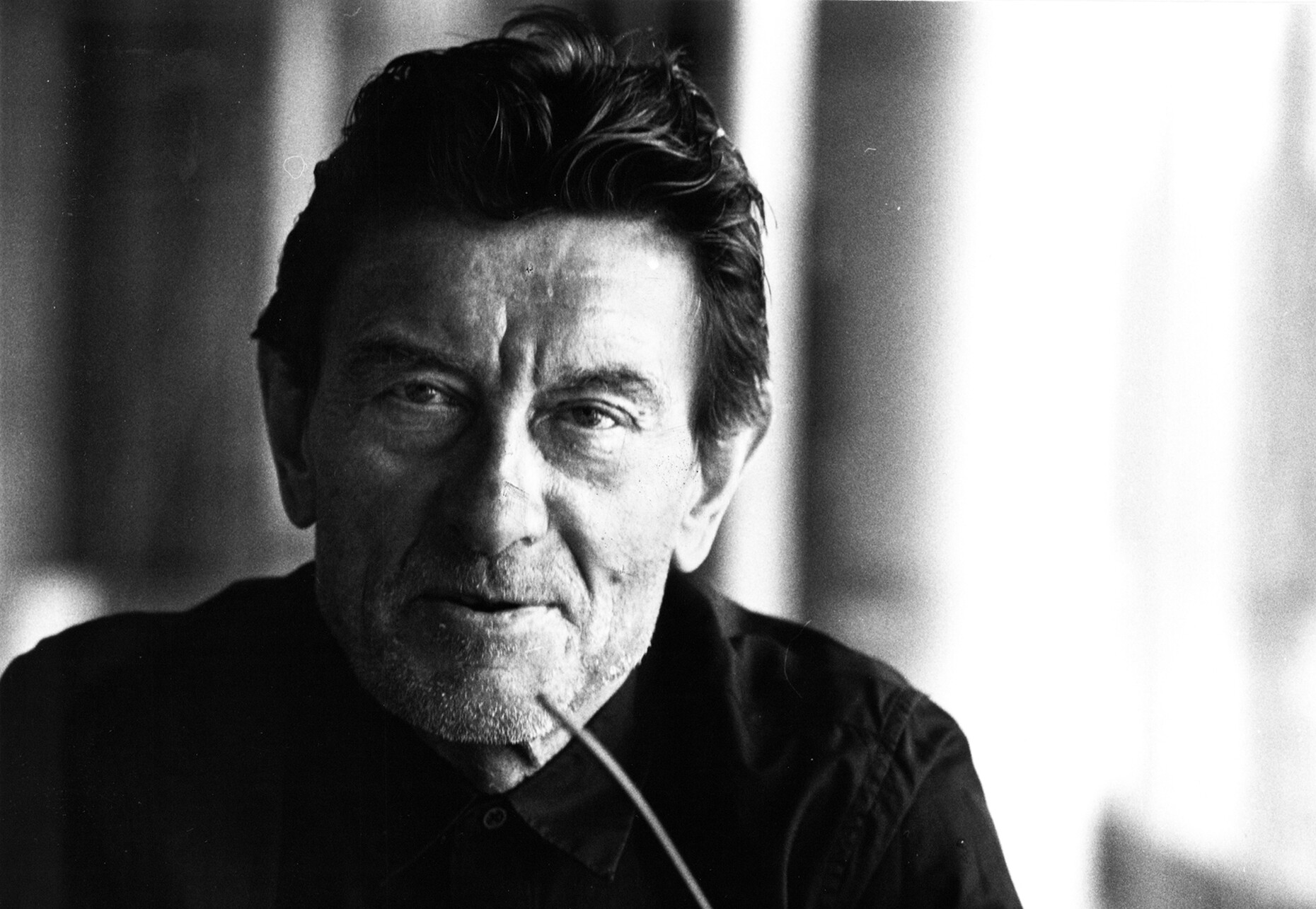

OBITUARY

Reaching for the skies right up till the end

Jahn’s career was near picture perfect. Born in 1940 in Zirndorf outside Nuremberg, he studied Architecture at TH München, graduating in 1965. He then headed for Chicago to do postgrad work at the Illinois Institute of Technology; among others because of the great old Mies van der Rohe, whom Jahn got to know there shortly before the famous master architect died. In Jahn’s early work there are many echoes of van der Rohe’s extremely pared back architectural idiom, that “Classical Modernism”, clear and reduced to the essentials. Helmut Jahn got a job in the large architectural practice of Charles Murphy in Chicago, where from the very beginning of his career he participated in large projects, court houses, libraries, sports and congress halls, office complexes, banks. That was the scale he felt most at home with and was likewise the scale on which he liked building throughout his life.

Under Murphy he steadily worked his way up through the ranks. Six years after joining, he was appointed “Director of Planning and Design”, then partner and from 1983 onwards the practice as called Murphy/Jahn. Murphy himself increasingly withdrew from daily business but out of loyalty to his erstwhile mentor Jahn for many years left the company name unchanged. Not until 2012 was it renamed – and has henceforth operated simply as JAHN. It was actually one of those famous American careers that would make the stuff of a movie: from rags to riches or rather as far as one can get rich in architecture. At any rate, Jahn became famous and emerged as one of the best-known German architects, realizing projects on four continents.

Needless to say, his architectural idiom changed over time. By the 1970s, there was increasingly less of Mies van der Rohe’s notion of “Less Is More” left over. Jahn was now far more interesting in building technology and engineering, and in ever more of his designs the technology and load-bearing structure themselves became undisguised themes. His breakthrough came with the “State of Illinois Center” in Chicago, which is now the “James R. Thompson Center” and which Jahn developed in 1979-1985. The semi-circular open and glazed atrium that runs the entire height of the building with its red metal staircases and glass elevator cars is not only a symbol of transparent American democracy, but Jahn thus also proved that he was fast becoming one of the key champions of the high-tech architecture of that era, alongside Richard Rogers and Norman Foster in Britain or Renzo Piano in Italy. As with the Centre Pompidou in Paris or the Lloyd’s Building in London, the technical fit-out of the building, the ventilation pipes, escalators and elevators were given a visible presence behind large glass walls in the transparent façade as if in glass display cases. These buildings gleamed and glittered in metal and glass. In a metaphorical sense they exuded the unconditional faith in high-grade technology being able to bring about a better built future. These are edifices attesting to an optimism in progress and a belated “Moon Age” where humans face no limits.

That said, Jahn developed his own style, by adding a sprinkling post-Modern elements and quotations from architectural history to his designs. In Frankfurt he placed a curious pyramid on the top of the Messeturm (1985-1990), as if what was at the time the highest building in Europe were merely a well-sharpened, albeit very large, pencil. Buildings such as One Liberty Place in Philadelphia, the City Spire Center in New York or the Bank of America Tower in Florida look as if they were slotted together from different building components to create one smooth, aerodynamic figure. Like his British colleagues Rogers and Forster, Jahn was likewise interested in boats and cars, and his yacht “Flash Gordon 6” among other things won the “Farr 40 North American Cup”. His architecture underscored these interests, presenting the forces involved and seeking to eschew anything superfluous to emulate the smooth, gleaming shape of an airplane, a powerboat or a limousine.

Jahn built and built. No one has ever counted how many altitude meters or square meters he totaled, but we can be sure the figures were huge. They ranged from Bangkok International Airport to the Charlesmagne Building for the EU Commission in Brussels to the Shanghai New International Exhibition Center. He was repeatedly invited to design buildings in Germany, too, when people hoped for a little glamor in the form of these gleaming glass-and-steel architecture: He designed the Airport Center and the Highlight Towers in Munich, the Post Tower in Bonn, and Terminal 2 for Cologne-Bonn Airport, not to mention the Bayer corporate HQ in Leverkusen, the Weser Tower in Bremen, and the Sony Center as well as the “Bahntower” on Potsdamer Platz for a reunified Berlin - and a lot more besides. However, like the names of the buildings, the designs are often very commercial, which left him open to criticism for being more a businessman than an architect, or quite simply to being a “corporate architect”. Jahn gladly stoked this criticism in interviews, for example when summarizing his opinion on good architecture: “The best thing is if it results in a good building that also earns good money.” In 2019, an interview with him was published in “Welt am Sonntag” in which he emphasized that architects are not artists but “problem-solvers” who need to heed costs and schedules. He was evidently not bothered by the fact he was not held in high esteem as an artistic architect which he after all was given his constant search for an optimal solution to a problem in technical and engineering terms.

To the very end, Jahn was an architect who never stood still and for whom the question of a “style” or a discernible “signature” was never of major importance. Architecture, he felt, needed not only to be beautiful but have a strong future, and this forever egged him on to greater things, to find new solutions – with an architectural company that in addition to its head office in Chicago has for many years also had branches in Berlin and Shanghai. The business boomed, construction of a 243-meter-high residential tower in Chicago started recently and in Rottweil in southern Germany together with Werner Sobek in 2018 he realized one of his most remarkable towers: A 246-meter-high structure there climbs upwards in a soft spiral, throning high above the landscape and inside which elevators are tested – that invention which made the construction of high-rises possible in the first place.

The incredibly slender and high needle is not just an architectural masterpiece but also an edifice that quite superbly fits someone whose name is associated with high-rises – someone who till the very end reached for the skies although he had long since got there.