It takes place every two years; and this year's edition of BAU in Munich more than deserves the title "World's Leading Trade Fair for Architecture, Materials, Systems". It is not just that the complex of the Münchner Messe was completely booked out and in order to create more exhibition space the organizers dispensed with the lounges. For the numbers of visitors also rose by ten percent over last year's event. And that interest is very much in line with the forecast recently released by the ifo-Institute, which predicts an upturn in the construction sector in coming years.

Without a doubt, energy efficiency, solar-driven architecture and sustainability were the key topics of the fair. Everywhere you looked you encountered the words "green" and "sustainable", although it was difficult to distinguish amidst the trade-fair turmoil which manufacturers of building products were merely exploiting the huge "sustainability" trend as a marketing instrument and which firms are truly pursuing serious intentions in the guise of environmentally sound products. It ought meanwhile to be clear to everybody that endeavoring to preserve nature and the environment for subsequent generations is a given and a must. And yet - there is a lack of transparency in the world of sustainability. What makes a product sustainable? And in what regard? If its production uses little energy or recycled materials are employed? Or if the supplier does not have to transport things half way around the globe? Certification systems can certainly provide some help. That said, some certificates need to be revised or are simply not known to the consumer. The result: given the raft of certificates floating about you sometimes wish for a certificate for certificates so as not to lose sight of things.

The new European building products directive may prove to be the driving force behind the development of sustainable architecture. The legislation decrees that "the building, its building materials and parts must be recyclable after demolition", and: "Environmentally-friendly resources and secondary building materials must be used for the building." Currently the diversity of materials on a building site is confusing. While the auto industry, for example, has signed a recycling commitment which effectively halved the number of materials used in today's cars nothing of the like has happened in the construction industry, and yet roughly fifty million tons of building rubble is churned out every year, and only five percent at most is recycled. As for the construction industry, there is no real recycling of the materials used in the production process.

So-called "green buildings" should not only be energy-efficient but also make life healthier and more comfortable for their occupants. For example, the Fraunhofer Institute presented a mineral compound of modified zeolite at the BAU that reduces formaldehyde emission by forty percent. It bears remembering here that estimates show over 85 percent of all wooden industrial materials use adhesives containing formaldehyde. Formaldehyde pollutes the air and is even classified as causing cancer by the World Health Organization. Mapei, the world's largest producer of chemicals for the construction industry, has developed low-emission, certified adhesives and sealing agents for wall and floor coverings. Indeed, floor-covering maker Armstrong stands out for its holistic approach, which ranges from its head office in Lancaster realized as a "green building" through to product brochures printed using organic dyes. Armstrong's vinyl floorings can be recycled in full and its linoleum production plant in Delmenhorst has received ecological certification. Floorings made of bamboo are a possible alternative. Bamboo is the world's fastest growing plant, and takes just four years to develop an extensive wood structure. Manufacturers Bambeau or Moso offer parquet flooring made of bamboo and Moso uses adhesives with low formaldehyde emissions.

Similarly windows and facades, and by extension the entire building shell exert a tremendous influence on the indoor air quality, daylight incidence and natural ventilation. This is why sustainable building is such an important task for window and facade builders. Often such products are promoted with slogans such as "save energy" or "gain energy", in order to emphasize the outstanding technical properties of the respective facade systems.

Schüco in particular claims to be one of the giants of eco-friendly systems and relies on "green technologies". At the BAU, Schüco paraded its three energy categories. In the "E3" or highest energy category there are products for buildings that generate more energy than they use and then make available the direct current to power various other systems in the building. Such products quite rightly get top marks as regards use. But architects and building operators still do not get enough information about how the products are made let alone their disposal.

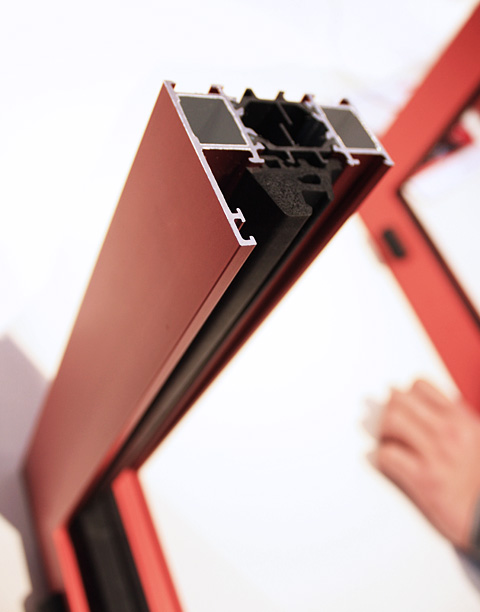

Wicona also proudly proclaims that it develops its systems "according to ecological criteria". "Wicline evo", which only recently hit the market, achieves its high insulating qualities among other things thanks to an enhanced corner connection technology and a special insulating section in the glazing rebate. In the form of "Coolstream", Colt, a supplier of technical equipment for buildings, presents a natural cooling system based on an adiabatic energy transfer using direct evaporation. Air is cooled by the evaporation of water, and the energy needed for evaporation is gained via a solar module.

In the end, the separate solutions the various manufacturers offer will need to be combined with one another. This is where the architect, planner and developer come onto the scene. Students from Rosenheim University demonstrated what the house of the future could look like. Their solar house came second in the Solar-Decathlon in Madrid, and was presented to a larger audience of experts at BAU for the first time. The solar house offers a haven from the seemingly unsolvable challenges facing us, an agreeable place in the mass of seemingly never-ending options on offer such a building trade fair. Fifty students spent two and a half years experimenting and building their modular house. The modules are 92-percent prefabricated, which means the house can be assembled in eight days. As for the materials used: seventy percent are renewable resources, while facade and solar shades are made of recycled sheet aluminum. The house produces four times as much electricity as it uses. Should the house go into mass production, 74 square meters would cost EUR 320,000. The list with all the items of good news is, in fact, much longer - and you can read up on it in the newly presented book "Solararchitektur 4 - Die deutschen Beiträge zum Solar Decathlon Europe 2010" / Solar Architecture 4 - The German Contributions to Solar Decathlon Europe 2010.

A plethora of new products that are seen as sustainable is all very well and good; but combining them intelligently is something else. It is only in a complete house that you will know whether the final item is really more than the sum of its parts. There is certainly no shortage of the latter, and they were shown in large numbers at the trade fair. But there is a definite need for feasible solutions that combine them. The construction industry faces a Herculean task - which it will not have mastered until all the sustainable solutions are intelligently combined in a house offering its occupants a pleasant, eco-friendly environment.

www.bau-muenchen.com

„coolstream“ by Colt

„coolstream“ by Colt

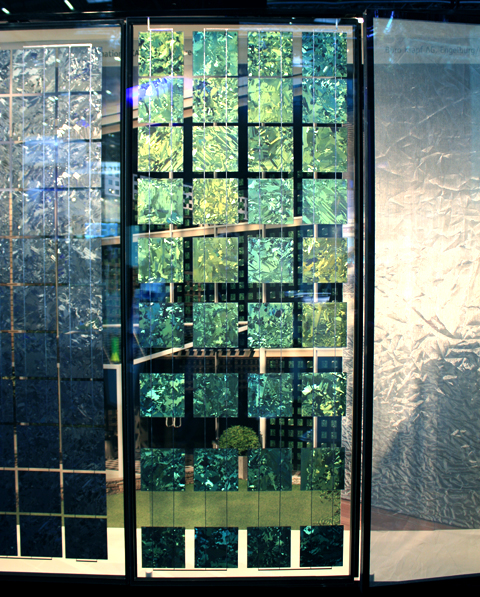

At Glas Marte

At Glas Marte

At Lamberts

At Lamberts

At Sedak

At Sedak

Installation at Trespa

Installation at Trespa

Dyckerhoff Weiss

Dyckerhoff Weiss

Kleinen Türenmanufaktur (KTM)

Kleinen Türenmanufaktur (KTM)

At Schüco

At Schüco

Insulating glazing at Okalux

Insulating glazing at Okalux

The solar home of Rosenheim

The solar home of Rosenheim

The solar home of Rosenheim

The solar home of Rosenheim

Wicona, High insulation window, all photos: Stylepark

Wicona, High insulation window, all photos: Stylepark

Akotherm

Akotherm

At Pilkington

At Pilkington

At Schott

At Schott

At Astec

At Astec

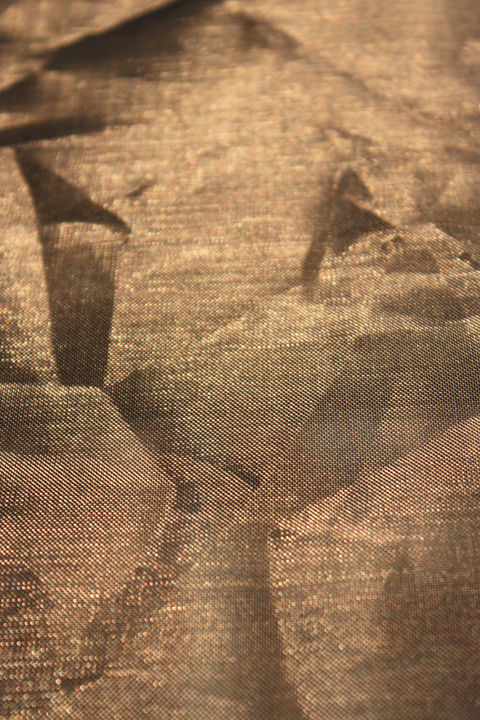

Wire mesh with bamboo at GKD

Wire mesh with bamboo at GKD

Bamboo Flooring by Moso

Bamboo Flooring by Moso

Transflooring Tour by Vorwerk Teppiche

Transflooring Tour by Vorwerk Teppiche

At Okalux

At Okalux

Synthetc material fabric between glass panes, "Okatech Vision" by Okalux

Synthetc material fabric between glass panes, "Okatech Vision" by Okalux

Okasolar by Okalux

Okasolar by Okalux

The solar home of Rosenheim

The solar home of Rosenheim