Gay Architects – Gay Architecture?

Take, for example, Fritz Schumacher and Gustav Oelsner, the leading lights in shaping the cityscapes of Hamburg and Altona as we know them. What the two had in common was their predilection not only for brickwork, but also for men. Schumacher helped Oelsner to elude pursuit by the Nazi regime, in part because of his Jewish roots. Another such icon is Helmut Hentrich, the mastermind behind Düsseldorf’s “Dreischeibenhochhaus”, one of the most important examples of postwar modernism. Hentrich escaped from the homophobic atmosphere of the Adenauer era at his self-designed castle in the more liberal atmosphere of Holland. In the international context, the attitude to the subject is less buttoned up. For many years now, Philip Johnston’s homosexuality has been mentioned in practically all the biographies, so in this volume there is only a note about it in the foreword. Here, for example, special chapters are devoted to the secret of the architect Paul Rudolph, the stories about the “hunt for gay college lecturers” and Charles Moore, “the architect in Playboy”.

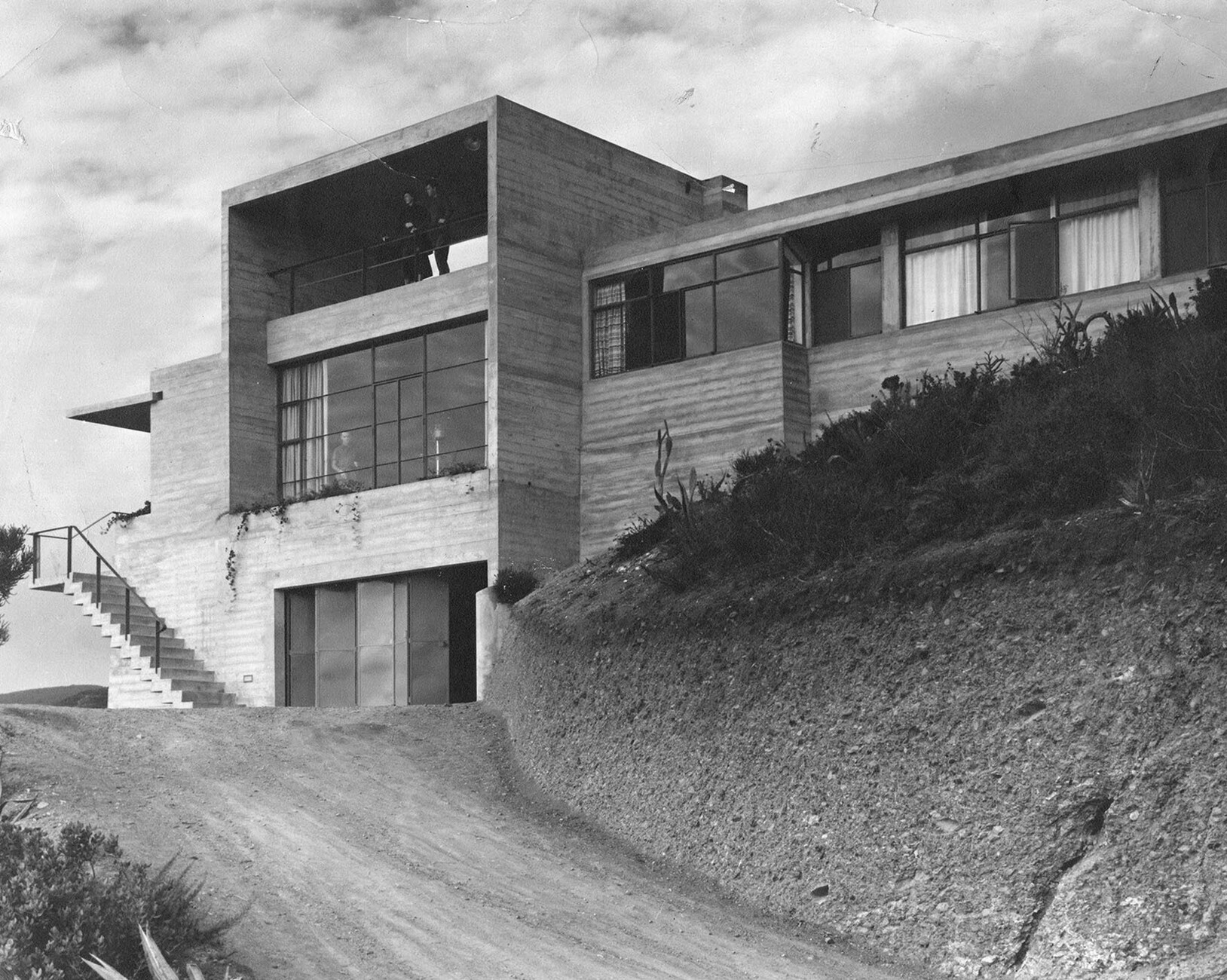

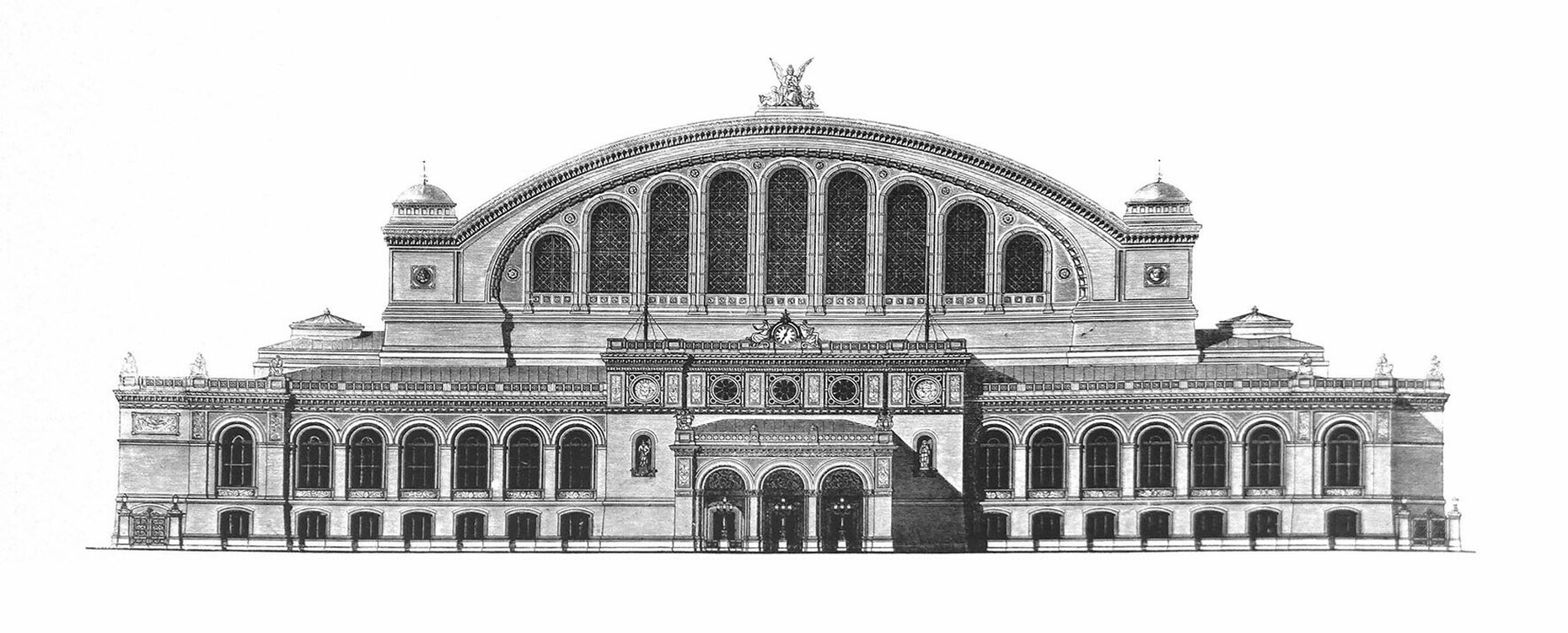

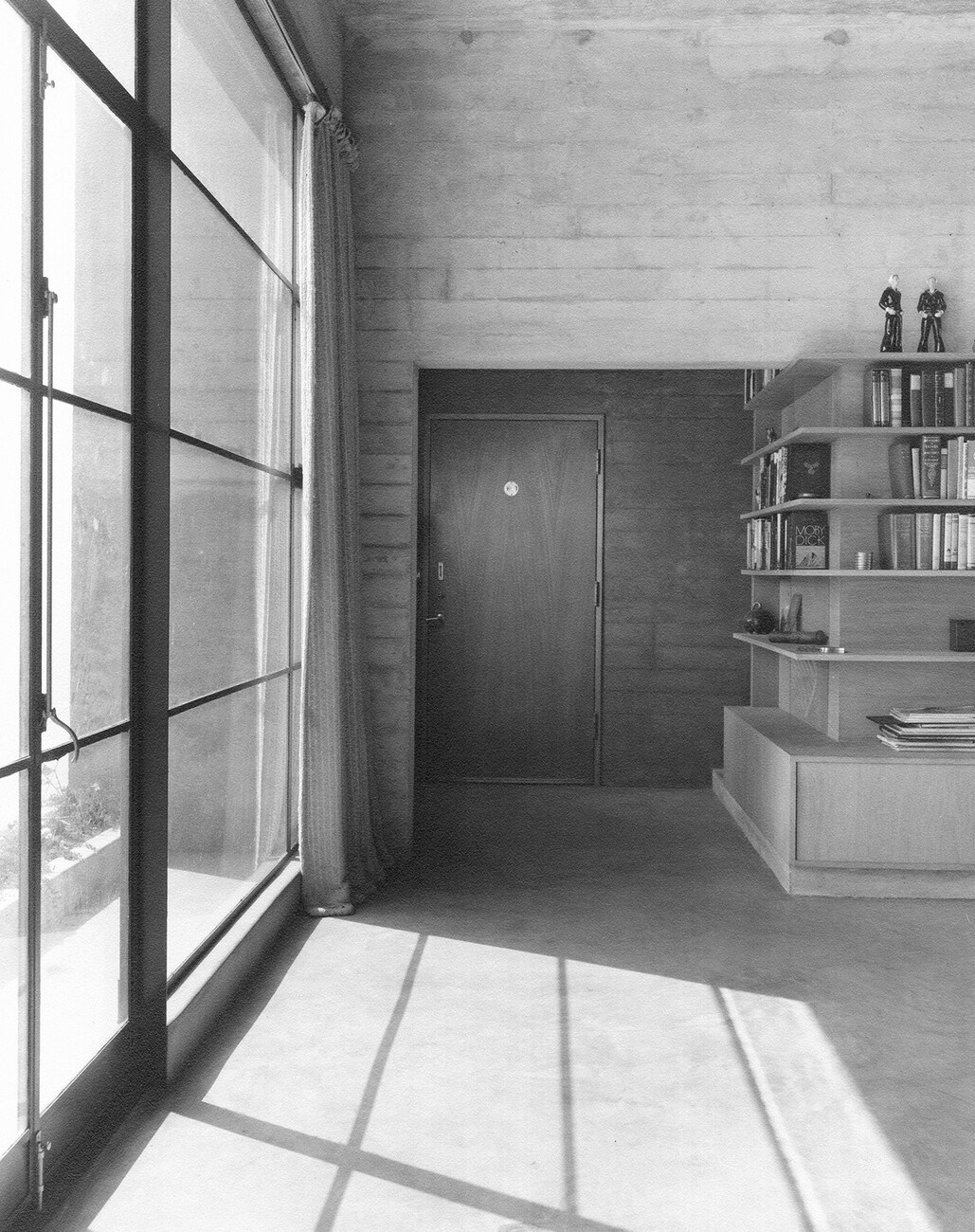

However, is architects’ sexual orientation really relevant when talking about their architectural vocabulary, does such a thing as gay architecture actually exist? The authors have also attempted to address these questions. It is striking that many of the buildings presented appear to be characterized by the aspect of concealment, in exactly the same way that their authors had to conceal their own true selves and could not publicly reveal their leanings. The buildings they constructed for themselves or their clients were erected in remote locations under extremely challenging circumstances in terms of access, orientation and visual privacy. The resulting floorplans gave the impression of being ideal for masking their occupants’ intimate circumstances. For example, Raymond McGrath designed the kind of rooms in which the beds could be slid into niches in order to hide shared bedrooms. William Alexander created an enfilade of bedrooms for a “ménage à trois”. Another clever touch is the layout of Paul Rudolph’s New York penthouse which allowed for vistas across glass washbasins and the bottoms of pools out into the more private rooms. Although visitors did not get a clear picture of the actual layout, they did receive the impression that there was another hidden dimension to things – not only to the apartment, but also to its owner’s life. Arthur Erikson and his life partner Franciso Kripacz, who led a dissipated existence, also exerted an influence on or even went as far as shaping the architecture of and interior design for the houses of North America’s high society. Erikson’s signature style even echoes, to a certain extent, the queer Gothic style of a Horace Walpole in the 18th century. Opulent scenarios or consistent minimalism, sometimes even a soft spot for lavish ornamentation or a focus on only the best materials resulted in vivid and exciting expressivity on the part of their authors. It was almost as if they were sublimating the fact that they had to suppress so much of their private lives.

As commendable as the two authors’ impressive search for clues undoubtedly is, unfortunately the book reaches its conclusion at the end of the 20th century, without even looking ahead or mentioning contemporary developments. A follow-up volume would be a good idea, a work that continues the fascinating story of queer architects and their oeuvre. Even though the authors do make an effort, the work is as dominated by men as the history of architecture. At any rate, there is a portrait of Germany’s first female architect. Emilie Winkelmann was a woman who lived her life as a lesbian. She studied at TH Hannover, where, in those days, she was refused a degree. Nevertheless, she did establish her own offices in Berlin. She was responsible for a large number of noteworthy edifices in the Reformstil, a style that was popular at the time, and she was accepted as a member of BDA, the Association of German Architects, in 1928. Another great protagonist graced with a mention in this volume is Hildegard Schirmacher. It was only at the end of a successful career as an architect and a home life as a married father that she came out as transgender and started living openly as a woman.

Referring to architecture and the history of building as “queer” in this context is something that is as overdue as it is culturally enriching. The book presents the lives and work of a large number of well-known icons of architecture in a way that is not only well-grounded in its subject matter but also a pleasure to read. It thus makes a considerable impact on the research into queer perspectives in architecture and the history of construction in the German-speaking countries. It is to be hoped that it will be followed by many more, likewise in the form of scholarly works. Congratulations to both the authors and the publishers Gerwin Zohlen who had the gumption to publish this volume at their specialist publishing house.

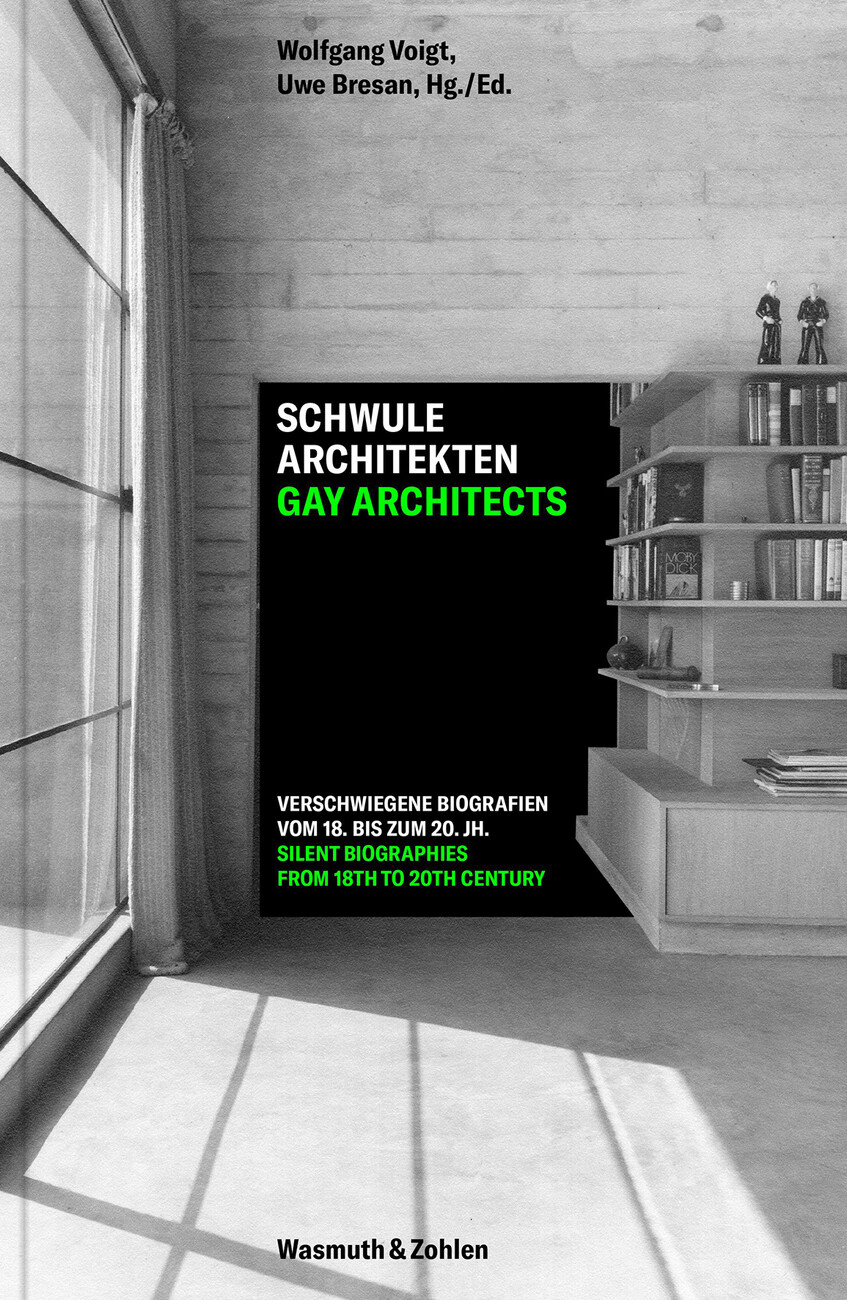

Schwule Architekten – Gay Architects

Verschwiegene Biografien vom 18. bis zum 20. Jahrhundert – Silent Biographies from 18th to 20th Century

Autors: Wolfgang Voigt, Uwe Bresan

Wasmuth & Zohlen Verlag

Language: German/ English

ISBN: 978 3 8030 2378 0

39,80 Euros