You can barely open the newspaper without finding a feature on occasion of the 80th birthday of a philosopher, writer, actor, composer, film maker, art historian, and occasionally a designer. Are there commonalities among those born in 1932? The fact that the designers we are going to consider here have each created an extensive and consistent body of work cannot be attributed to their age alone.

1932 stands for continuous action, evaluation and the development of ideas once encountered. Products and the procedures that bore them were conceived to last throughout the years. Designers often followed the same approach across decades. This tenacity is not always easy to deal with for those around them. The lives and works of the designers born in 1932 seem to be dedicated to the “slow boring of hard boards”, “it takes passion and perspective,” as sociologist Max Weber expected of the politician’s profession back in 1919.

External circumstances

For those who tend to arrange historical events chronologically, 1932 was dominated by the greatest normality. In fact, it was in this year that the global economic crisis reached its climax in Germany. And in 1932, for the very first time, democracy’s enemies – the Nazi party, but also the Communist party – received more votes and seats in parliament than all of the democratic parties combined. A side note: The Bauhaus was also forced to leave Dessau in 1932. The most prominent educational institution for experimental design in Germany was closed down due to pressure from the political right and thus retreated to Berlin. All those born in this year of great transition in Germany would have lived their childhood and early youth during the Nazi reign and by the end of the War could have found themselves anywhere but not necessarily at home.

Enzo Mari recounts that as the family’s oldest son in Milan he was forced to put bread on the table. Graduating school was out of the question. But he was able to enroll at the Brera Academy of Fine Arts. However, whether it was painting, sculpture, or scenery, Mari always asked too many questions and always received the wrong answers. For Ingo Maurer, born on the island of Mainau to a Lake Constance fisherman, studying was certainly not a realistic option. He took on a bread-and-butter job and became a typographer, “you learn a lot about sight and perception there,” recalls Maurer. The loss of a parent, migration, escape: All of these things seemed to have been predestined for the generation of 1932. This was also the case for Rolf Heide, who first moved to the Danzig area with his family but later fled back to Kiel. Hans (Nick) Roericht was also forced to leave his Silesian birthplace. The house belonging to the parents of Finnish designer Eero Aarnio was hit by a Russian bomb. While at the boarding school attended by Dieter Rams, outdoor paramilitary games were more important than learning foreign languages, for example. All of this is far removed from today’s concept of childhood.

But they weren’t happy with the way the adults went about reconstructing their world. The old political, social and not least aesthetic order lived on in a new guise. So from the mid-1950s onwards a new generation began to stake their own claim. “There is always a leap from the Bauhaus into the 1960s. What lies in between is denied,” says Rolf Heide of the aesthetic ideals of those born in the same year. But who are the protagonists of the 1932 designers?

Room capsules

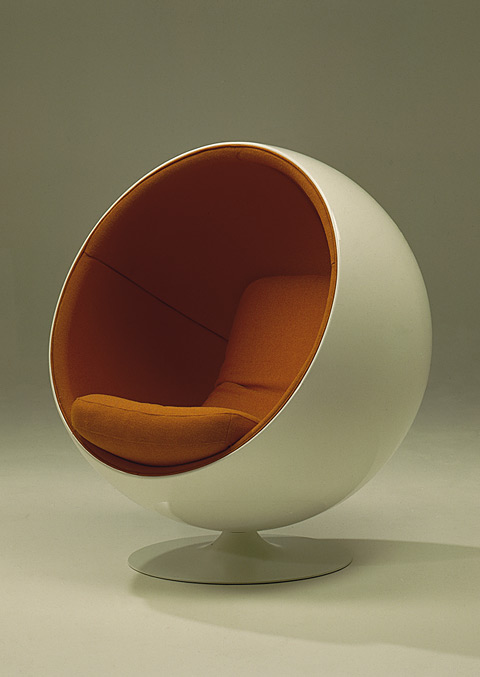

In 1962, Eero Aarnio opened his first office for industrial and interior design, specializing in furniture made from synthetic materials. His creations are classified as visionary “space design”, he makes room capsules, which also come with the option of integrated telephones or stereo speakers. These psychedelic places of retreat are surrounded by a protective shell, like the “Ball Chair”, presented in 1966, or the transparent “Bubble Chair”, released in 1968. With “Pastilli” (1968) and “Tomato” (1971), he created items of furniture that upon first glance cannot be assigned to either the indoor or outdoor space. Tillmann Prüfer wrote about Aarnio in the German weekly “Die Zeit”: The designer “honored the naïve view of progress” and “had the special talent of formulating astonishment.” A statement that can be applied to almost the entire generation of designers born in 1932.

Diversity and unity

If there were such a thing as a global superstar of German design, it would be Dieter Rams. He started out at Braun in 1955 as an architect and interior designer and some years later became widely known for his work there as head designer, a role he held from 1961 through 1995. The Braun designers showed the world how to consolidate diversity and unity. Dieter Rams provided theoretical summaries of all of his knowledge of the design process, which culminated in the statement: “Good design is as little design as possible.” His vision of a world “tidied up” by designers was not always a popular one, but has now assumed utopian aspects. When Rams had already been in retirement for some time, Apple and its Head Designer Jonathan Ive declared the earlier designs produced by Braun under Rams as prototypes for good design, as role models. He also worked for Vitsoe as a freelancer, creating furniture systems, which have since been adapted to meet today’s requirements. He also spent time teaching at the University of Fine Arts in Hamburg. Almost a personality cult: His former studio at the University is soon to be installed in Hamburg’s Museum of Arts and Crafts as a “period room”.

Outlook

Rolf Heide completed a carpenter’s apprenticeship in “medieval rigor”, before his teachers at the Muthesius Academy in Kiel, Eduard Levsen, showed him a whole new world of possibilities in design. Like Rams’ teacher Hans Soeder at the Art Academy in Wiesbaden, Levsen sought to draw upon the experiences of 1920s Modernism. There was a keen focus on terms such as “necessity” in their teachings. The designer is driven by the need to turn things around, to act pragmatically making the best out of what is available, and trying out new forms and constellations in the process. From 1959 Heide worked for a number of German consumer magazines in Hamburg, such as “Brigitte”, then “Schöner Wohnen” and “Architecture & Wohnen”. He positioned interior design objects as constitutive parts of everyday life. As manufacturers began to transform into brands, Heide aided companies such as Bulthaup, Duravit, Gaggenau and Interlübke to position their values and products on the market. And if Heide thought something was missing from the market, he simply designed it himself; such as luminaires for Anta or the highly popular stackable bed, which was originally conceived for “Brigitte’s” working female readers. Heide’s earlier pieces could be disassembled, making them easy to ship to customers. He created a complete collection for “Wohnbedarf”, as well as a series of furniture systems for Interlübke, e.g., the “SL-Wand” system and the vertically oriented “Travo” system.

The object’s little secret

In 1958, just a young member of the “Stylistics” department at Daimler Benz at the time, Richard Sapper handed his superiors a bundle of his own drawings and concepts. The boss was bowled over by the quality of his work but said: “Of course we will never actually make cars like that.” Sapper realized straight away how little scope there was for him and his work in a “huge corporation”. He gave up his secure job there to go to Milan. Sapper worked for Gio Ponti and joined forces with Marco Zanuso’s partner to design telephones, TVs and innovative plastic furniture. Sapper’s designs always have some little secret, which they then reveal as soon as you use them: like the “Tizio” table lamp (1972), which poises itself in perfect balance. The same goes for the “Static” table clock (1959), which leans toward the user and looks as though it will fall at any second, the “TS 502” radio (1964), the Alessi espresso machine “9090” (1978) and the IBM computer designed by Sapper. The designer has been advising IBM and the successor firm Lenovo since 1980, as an external head designer with a consultative status, as it were. Speaking of his many years of teaching in Stuttgart he once explained: “There are two things that play a role in design education: The example set by the teacher and the quality of the student community, which is for its part influenced by the teacher’s example.” And Richard Sapper’s products are still coming onto the market. Those who are looking for a system that allows them to view several displays alongside one another will surely come across the “Sapper Multiple Monitor Beams” (Knoll, 2011), which can be used to combine screens to create large “work altar”.

Bulbs can do anything

Ingo Maurer set out from Lake Constance into the great wide world. As a typographer he travelled to the United States, which even today remains the designer’s second home, though Munich is his chosen residence. A naked Edison light bulb that was hanging from the ceiling provided the inspiration for his second career as a “lamp maker”, as he termed his calling, or a “light poet”, as others described him. Maurer once defined the light bulb as such: “It has an insanely beautiful shape, it is strong, you can burn your finger on it, it is breakable – it unites technology and poetry.” Maurer has been designing lighting since 1966 and has long since ceased to place a shade over them to cover them up. He gives the light bulb itself wings; it disappears, and is sometimes even surrounded by exploding porcelain. Maurer conceives lighting to present the room, explores new technologies such as LED and OLED, without revoking his loyalty to the light bulb in the process. Together with his team, he designs lighting series and individual pieces, works on large projects, such as the lighting concept for Munich’s new subway stations. And is one of the few designers born in 1932 who is not afraid of a bit of kitsch at times, when he revels in glittery materials but then he reveals a more technically elaborate luminaire up his sleeve.

It’s all about the project

Enzo Mari is thought of as “pensive” person; they say he’s a “provocateur”. In other words: His truths are even more uncomfortable than other designers. Trying to follow his thoughts is somewhat strenuous but is most definitely worth the effort. One central term for Mari is “project”, whereby designers, craftsmen and companies agree on an ethical goal but not by means of a declaration of intent or such but rather a common research process. In this way, Mari criticizes the inconsistency seen in many companies, which tend to withdraw from the project’s development entirely handing this over to the designer alone. For Mari, the most important over-arching project is dissuading people from their conditioning by the “market god”. In contrast to his complex theoretical reflections, his works appear rather direct and emotional. They include play elements for children, such as a zoo made of 16 wooden animals that fit together (Danese, 1957), as well as furniture like the collapsible, easy-to-transport “Box Chair” (Castelli, 1971), the elegant “Tonietta” chair (Zanotta 1980/85) and the porcelain service “Berlin” (KPM, 1995). Mari, who teaches in Italy, is also an honorary professor at Hamburg’s University of Fine Arts. His 1973 “critical design practice” was recently taken up by a group of young designers in the form of “Autoprogettazione 2.0” and subsequently presented as part of the “The Future of the Making” in Milan.

Online understanding

From 1955 onwards Hans (Nick) Roericht studied at the University of Design in Ulm, going on to teach there after his studies; in 1966/67 he also lectured at several universities in the US. In addition to this, he founded his own company in Ulm. In 1959 Roericht achieved something that most students only dream of: His final university project resulted in a coveted serial product. Even today, the stackable porcelain tableware for use in hotels “TC 100” caters to the needs of many a hotelier. Roericht later spent the years between 1973 and 2002 teaching at Berlin’s University of the Arts. The list of his students is not only long, it is impressive, too: Egon Chemaitis, Inge Sommer, Werner Aisslinger, Oliver Vogt, Herrmann August Weizenegger and Judith Seng to name but a few. As part of Otl Aicher’s “Entwicklungsgruppe 5”, Roericht worked on the corporate design for Lufthansa and the Olympics. And with his own website he demonstrated exactly what “going online” can mean. While the Nick Roericht Foundation, established by the artist himself, makes studies, teaching concepts, interviews, product posters, exemplary projects, work outcomes and feasibility studies, as well as his students’ university accessible for everyone: Everything that Hans (Nick) Roericht has collected can be viewed and read here. Some of his office furniture is still sold by Wilkhahn today. And even the porcelain series, now made in China, can be ordered for home delivery.

Perhaps we have overlooked it with all the birthday celebrations. Indeed, the designers of 1932 do exist, they are united by a humanist impetus and enrich our lives and thoughts with one new kind of design after the other.

Dieter Rams, photo © Dieter Rams

Dieter Rams, photo © Dieter Rams

”audio 300” by Dieter Rams for Braun, 1969, photo © Braun

”audio 300” by Dieter Rams for Braun, 1969, photo © Braun

”SK 4 Phonosuper” by Hans Gugelot and Dieter Rams for Braun, 1956, photo © Braun

”SK 4 Phonosuper” by Hans Gugelot and Dieter Rams for Braun, 1956, photo © Braun

”TP 1” Phono-Transistor with ”T41 Taschenempfänger“ (1962, top) and ”P1“ Batterieplattenspieler (1959, bottom) by Dieter Rams, photo © Braun

”TP 1” Phono-Transistor with ”T41 Taschenempfänger“ (1962, top) and ”P1“ Batterieplattenspieler (1959, bottom) by Dieter Rams, photo © Braun

“TG 60“ by Dieter Rams for Braun, 1965, photo © Braun

“TG 60“ by Dieter Rams for Braun, 1965, photo © Braun

“Studio 2“ by Dieter Rams for Braun, 1959, photo © Braun

“Studio 2“ by Dieter Rams for Braun, 1959, photo © Braun

Richard Sapper, photo © Alessi

Richard Sapper, photo © Alessi

“Tizio“ by Richard Sapper for Artemide, 1972, photo © Teo Jakob, Kunsthalle Bern

“Tizio“ by Richard Sapper for Artemide, 1972, photo © Teo Jakob, Kunsthalle Bern

“TS 522“ by Marco Zanuso and Richard Sapper for Brionvega, 1963, photo © Holger Ellgaard

“TS 522“ by Marco Zanuso and Richard Sapper for Brionvega, 1963, photo © Holger Ellgaard

”9090” by Richard Sapper for Alessi, 1978, photo © Aldo Ballo, Alessi

”9090” by Richard Sapper for Alessi, 1978, photo © Aldo Ballo, Alessi

”9091“ by Richard Sapper for Alessi, 1984, photo © Aldo Ballo, Alessi

”9091“ by Richard Sapper for Alessi, 1984, photo © Aldo Ballo, Alessi

Enzo Mari, photo © Zanotta

Enzo Mari, photo © Zanotta

“Aran“ by Enzo Mari for Alessi, 1960, photo © Alessi

“Aran“ by Enzo Mari for Alessi, 1960, photo © Alessi

”Museo” by Enzo Mari for Zanotta, 1991, photo © Zanotta

”Museo” by Enzo Mari for Zanotta, 1991, photo © Zanotta

“Tonietta“ by Enzo Mari for Zanotta, 1980/85, photo © Zanotta

“Tonietta“ by Enzo Mari for Zanotta, 1980/85, photo © Zanotta

“Ulm“ by Enzo Mari for Zanotta, 1996/98, photo © Zanotta

“Ulm“ by Enzo Mari for Zanotta, 1996/98, photo © Zanotta

Hans (Nick) Roericht, photo © Wolfgang Siol, archive Hans (Nick) Roericht

Hans (Nick) Roericht, photo © Wolfgang Siol, archive Hans (Nick) Roericht

“TC100“ by Hans (Nick) Roericht, 1959, photo © Wolfgang Siol, archive Hans (Nick) Roericht

“TC100“ by Hans (Nick) Roericht, 1959, photo © Wolfgang Siol, archive Hans (Nick) Roericht

Eero Aarnio, photo © Adelta

Eero Aarnio, photo © Adelta

”Ball Chair” by Eero Aarnio, 1963/66, photo © Adelta

”Ball Chair” by Eero Aarnio, 1963/66, photo © Adelta

”Bubble Chair” by Eero Aarnio, 1966, photo © Adelta

”Bubble Chair” by Eero Aarnio, 1966, photo © Adelta

”Tomato Chair” by Eero Aarnio, 1971, photo © Adelta

”Tomato Chair” by Eero Aarnio, 1971, photo © Adelta

”Pastil Chair” by Eero Aarnio, 1967, photo © Adelta

”Pastil Chair” by Eero Aarnio, 1967, photo © Adelta

Rolf Heide, photo © Philip Glaser

Rolf Heide, photo © Philip Glaser

”EM Stapelliege” by Rolf Heide, photo from 1966, photo © Wohnbedarf

”EM Stapelliege” by Rolf Heide, photo from 1966, photo © Wohnbedarf

Two exemplars of the ”EM Stapelliege”, photo © Müller Möbelwerkstätten

Two exemplars of the ”EM Stapelliege”, photo © Müller Möbelwerkstätten

“S 07“ by Rolf Heide and Peter Krähling for Interlübke, 2012, photo © Interlübke

“S 07“ by Rolf Heide and Peter Krähling for Interlübke, 2012, photo © Interlübke

”Travo” by Rolf Heide for Interlübke, 1998, photo © Interlübke

”Travo” by Rolf Heide for Interlübke, 1998, photo © Interlübke

”Tuba” by Rolf Heide for Anta, 2000, photo © Anta

”Tuba” by Rolf Heide for Anta, 2000, photo © Anta

Ingo Maurer, photo © Albrecht Bangert

Ingo Maurer, photo © Albrecht Bangert

”Bulb” by Ingo Maurer, 1966, photo © Ingo Maurer

”Bulb” by Ingo Maurer, 1966, photo © Ingo Maurer

“Birdie“ by Ingo Maurer, 2002, photo © Tom Vack

“Birdie“ by Ingo Maurer, 2002, photo © Tom Vack

“LED Bench“ by Ingo Maurer, 2002, photo © Tom Vack

“LED Bench“ by Ingo Maurer, 2002, photo © Tom Vack

“Lacrime del Pescatore“ by Ingo Maurer, 2009, photo © Tom Vack

“Lacrime del Pescatore“ by Ingo Maurer, 2009, photo © Tom Vack

“LED Wallpaper“ by Ingo Maurer, presented in 2007 for the first time, photo © Tom Vack

“LED Wallpaper“ by Ingo Maurer, presented in 2007 for the first time, photo © Tom Vack

“Stitz 2“ by Hans (Nick) Roericht at Wilkhahn, 1991, photo © Wilkhahn

“Stitz 2“ by Hans (Nick) Roericht at Wilkhahn, 1991, photo © Wilkhahn