Obituary

On the death of Florence Knoll Bassett

On January 25 of this year Florence Knoll Bassett passed away in Miami. Since then, a large number of obituaries have been published describing her life. Even those media which normally only write about design and interior design in their “style” sections have penned articles in her memory. In this Bauhaus anniversary year, a jubilee that will be particularly celebrated in Germany and that offers many opportunities for well-meant self-adulation on the subject of the politics of aesthetics, Knoll offers a different, albeit related point of reference within the recent history of design and architecture. And she distilled everything that Modernism came up with in terms of furniture design in the first third of the 20th century into the kind of mass-produced furniture with an international appeal that became the basis of what has now become omnipresent mid-century Modernism. Florence Knoll worked as a designer, often in collaboration with other people.

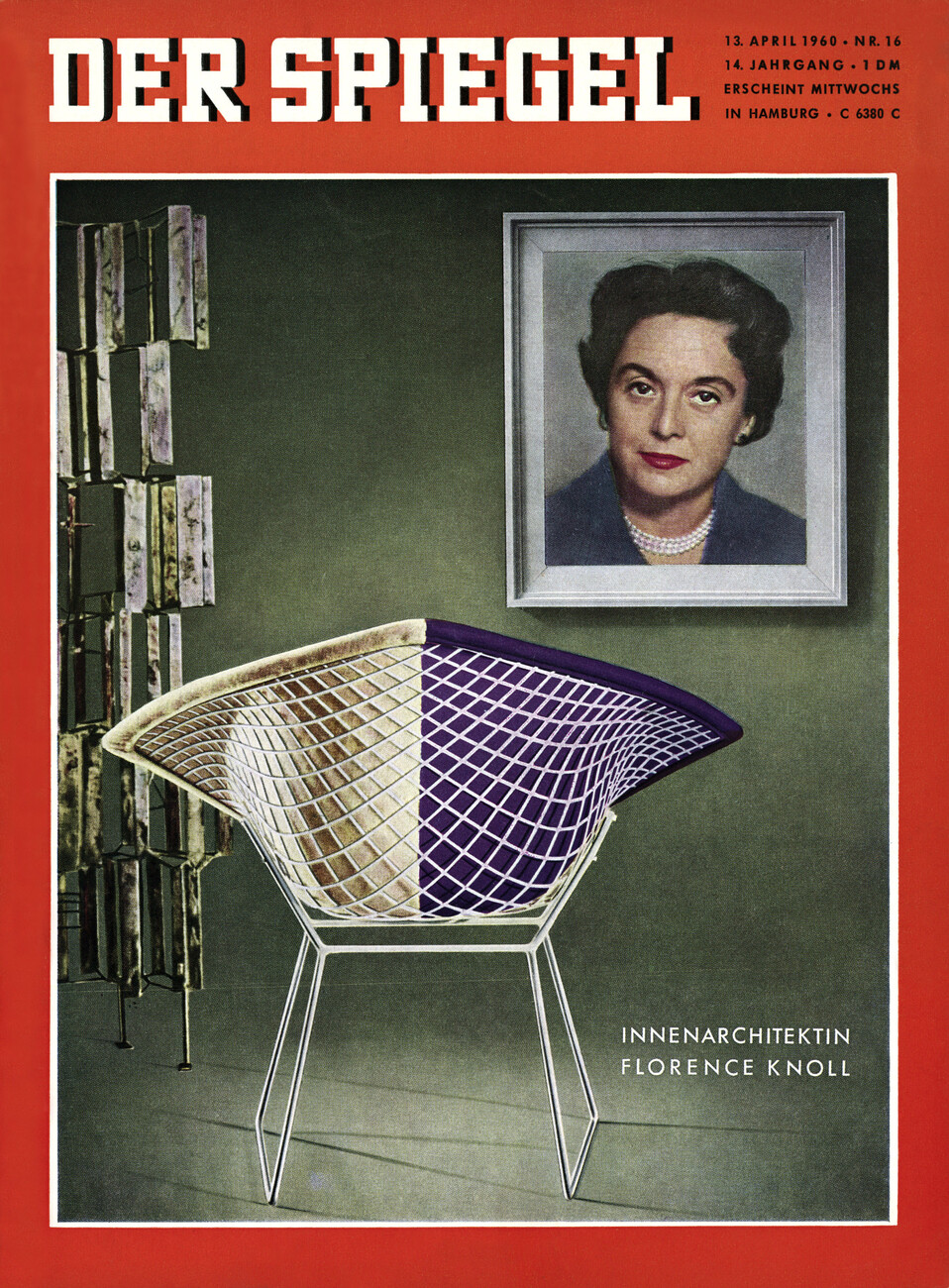

A clear understanding of the fundamentals of economic viability informed her approach to her work. She designed furniture herself whenever she did not see any possibility to use existing solutions. She established an international network of creatives consisting of her peers from student days and their teachers and involved them in product design for Knoll International. She was right there on top for only a comparatively short period of time. She became famous throughout the world, far beyond the scope of specialist circles. In 1960, when she was in the process of selling her company, “Der Spiegel” devoted a cover story to her. And although she retired in 1965 she remained a paramount example and point of reference of a businesswoman, an interior decorator and a designer. She repeatedly inspired new generations with her professional way of looking at design, which went far beyond attributions concerning what constitutes the masculine or feminine in design. Reflecting on Knoll’s life and work is more important than ever before because it highlights the kind of areas that offer people a chance to experiment with creativity, something that is often called for in theory, but all too often fails in practice.

Knoll was born Florence Marguerite Schust on May 24, 1917 in Saginaw, Michigan, a town then known for timber. At the time, the American Midwest spawned significant innovations in the car and furniture industries. This applies not just to the products, but also to the manufacturing and marketing strategies. The Schusts were a well-off family. Her grandfather, who operated a wholesale bakery, emigrated with his family from Switzerland to the United States. Florence’s father ran the company. He died when she was five years old. She lost her mother when she was 12 after which she was sent to boarding school, choosing one in Bloomfield Hills, northwest Detroit. Her art teacher there, Rachel de Wolfe, introduced her to architecture and design, and to the planning side to the profession. Then, at the age of 15, she was allowed to try her hand designing a two-story residential building – including all the necessary details and the interiors. This was when her decision to become an architect first took root. Finnish architect Eliel Saarinen and his wife Loja were leading figures on the creative scene in Bloomfield Hills, inspired by the Arts-and-Crafts movement and active in a critical discussion of the Art Deco trends of the day. Saarinen had designed both Schust’s school and the entire Cranbrook Educational Community campus, endowed by newspaper magnate and philanthropist George Gough Booth. Both these men welcomed Schust into their families.

The Cranbrook Academy of Arts was established in 1932. Eliel Saarinen was the founding president of the institution. While he was in charge of Architecture and Urban Planning at the college, Loja Saarinen headed the Weaving and Textile Design departments. At 17, Schust was busy immersing herself in the atmosphere at Cranbrook which soon developed into one of the most important schools of design and architecture. Eliel’s son Eero Saarinen, who was a few years older than Knoll, familiarized her with the history of architecture in illustrated letters he wrote. Later students at the academy included sculptor Harry Bertoia and designer Charles Eames. In 1984, writing about an exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum, the New York Times said that “like no other institution” Cranbrook had the right to see itself as a synonym for contemporary American design. At the beginning of the 1930s, Schust embarked on extended trips to Europe with the Saarinens. During a summer vacation in Finland Alvar Aalto advised her to go and study at the Architectural Association in London. She spent three years there but returned to the States in 1939 without completing her studies because of the war.

While she was still in London she came into contact with Marcel Breuer who organized an internship for her in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in the office he ran there jointly with Walter Gropius. In 1941, Schust finally completed the studies she had commenced in Cranbrook and continued in London, graduating from the Armour Institute of Technology in Chicago in 1941, taught by Mies van der Rohe. She later emphasized what a great influence the latter had been on her design work: He had, she said, helped her to clarify her vision. From Chicago she moved to New York, working for various firms of architects, where she was always the only woman. She was consulted about interior design projects and in this context she met a young German who had been living in New York since 1938. He was the eldest son of Herrenberg-based upholstered furniture manufacturer Walter Knoll and had established his own furniture collection. He now needed a designer for various interior-related assignments. The Hans Knoll label became Hans Knoll Associates which soon mutated into Knoll International, one of the major furniture companies. A key figure in this process was Florence Schust. The two fell in love and married in 1946. Florence Knoll established a system that was key to the company’s fame and growth: the Knoll Planning Unit, abbreviated to P.U. With its small team of designers she was as a result nevertheless able to accept large planning assignments. Although limited in size, the P.U.’s offices served to familiarize customers with the team’s approach to planning. And the unit impressed clients with the efficiency and coherence of the concepts it developed.

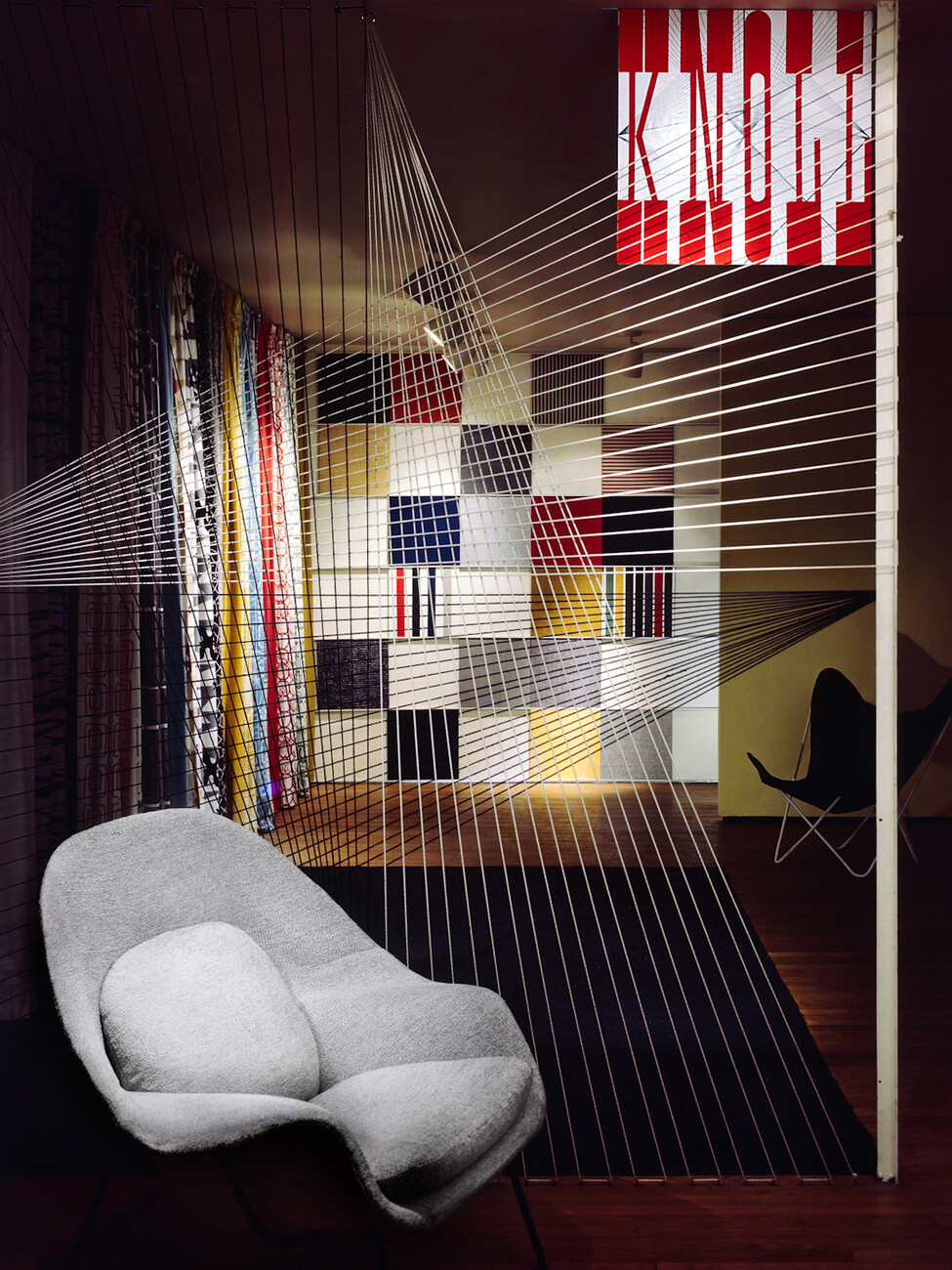

For Florence, new furniture was always a product of necessity. And it was almost in passing that, when she started mass producing “Barcelona Chair”, a chair designed by her former teacher Mies van der Rohe and dating from 1929, she launched the field of retro design. To this end she modified the pre-War hand-made version. Nevertheless, the manufacturing process remained complex. She once mentioned that at the time, in 1948, she simply needed such an item of furniture for the fit-out of larger rooms. It became one element of the globally popular Knoll style. Later, Knoll International acquired the production rights from Italian manufacturer Gavina and floated a re-edition of Breuer’s 1920s furniture designs. With Swiss born photographer and typographer Herbert Matter she came up with brand and advertising concepts and from 1946 through 1966 he acted as a consultant to the company. For Florence Knoll showrooms were not only places where you sold things, but spaces where you could highlight the collections. They were locations for creating distinction through product presentations – that thus differed, for example, in New York from those in Chicago, San Francisco or Los Angeles. With her furniture and textiles, her colors, her spatial and fabric concepts she created that cool, open-plan, homely office style which we now gaze at in wonder as “Mid Century Modern” in series such as “Mad Men”. We have now crammed the real offices and the apartments (to which her sofas and tables have long since migrated) with computers and all kinds of junk of the sort which we deem essential but which are irreconcilable with the clarity of a Florence Knoll. And thanks to family connections Knoll International rapidly established a presence in post-War Germany, more quickly than other innovative American furniture brands.

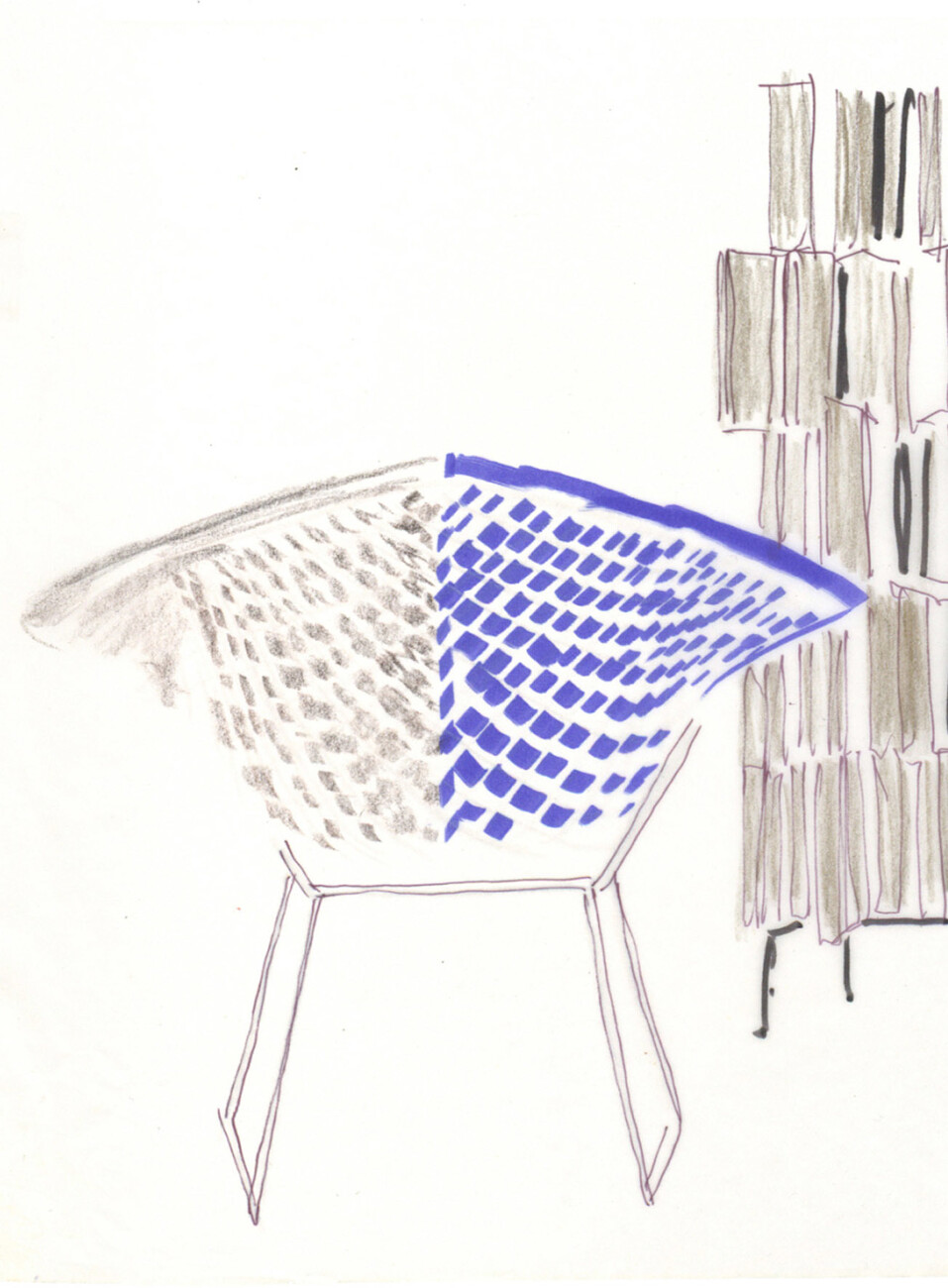

Hans G. Knoll died in a motoring accident in Cuba in 1955. An abrupt end to a love affair and a business relationship. Florence Knoll, who had anyway had the final say about questions of planning for a long time, took over the management of the company. It was her contacts that made new ideas possible. And as people in Germany recognized, this furniture from the United States was different from its competitors. West German textbooks such as Hatje’s “Neue Möbel” series have made it clear just how narrow-minded the luxury of the post-War West Germany actually was, even when it emphasized clear lines. Knoll set the tone and is still up-to-the-minute today. Herbert Bertoia, the sculptor and an acquaintance from her Cranbrook days, made Florence Knoll into the kind of furniture designer who devised iconic wire armchairs. Her office sideboards had fabric-covered fronts long before anybody else thought about acoustically effective furniture. With Knoll, marble found its way into the office and the apartment. But not as the customary heavy, sedate material but floating, almost airborne on the one-legged “Pedestal” table created by Eero Saarinen, whom she had known since her youth. When he, too, died unexpectedly in 1961, she stepped into the contract to provide the interior architecture for the CBS high-rise in New York that Saarinen had designed.

Once the job was complete, in 1965 and five years after she had sold the company, she retired from it. By this time her name was Florence Knoll Bassett, after banker Herbert Hood Bassett, whom she married in 1958. In 2000 she bequeathed her orderly archive to the Smithonian Institute: It contains drawings, photos and letters documenting her long, intensive life, as well as her short and equally intensive fight to combat huge billboards along the highways in Miami. The only time she dabbled in politics, as she put it. One can criticize the new paths taken in design in the 1950s and 1960s as an agenda for a liberal, affluent und mainly white international upper class, whose optimism was hardly shaken by the crises of that time. However, Florence nevertheless came up with exemplary, inventive designs that stood out for their pragmatism, she forged a network of artists and designers on whom she relied, and she opted for a clarity that enabled her to change the world and exploit opportunities without repeating herself. Florence Knoll Bassett will inspire us for many years to come.