What really happened in America?

Were they really equal “partners in design”, Alfred Barr Jr. and Philip Johnson? At the end of the 1920s Barr had long before found his solid place, his mission in life, as founding director of New York’s Museum of Modern Art. At that time Johnson was dabbling in philosophy who took his cue from Nietzsche, and it was only in 1940 that this erratic soul would begin his degree in architecture. But perhaps it was precisely this unequal, tense pairing that preconditioned the duo for that influential role as “pioneers of the Bauhaus in the USA”, which is not only determinedly claimed in the exhibition at the Bielefeld Kunsthalle, but at times even illustrated in picturesque form. For example with black and white photos alongside the relevant objects. Thus the chess table that belonged to Bauhaus member Heinz Nösselt (1924) is accompanied by a photo document from 1945: “Alfred Barr at the Julien Levy Gallery playing in a chess tournament”, which Marcel Duchamp turned into a genuine happening by reading aloud the relevant moves of the game.

A double “checkmate”, undoubtedly. Yet the correlation with the Bauhaus is not substantiated merely by the scene in the photo. Indeed there is no trace of Johnson. He was also nowhere to be seen when Barr visited the Inexpensive Articles of Good Design exhibition at Newark Museum in 1928, which visualized the merging of architecture with fine and applied arts, as propagated by the Bauhaus, in exemplary fashion. Barr used this as a model and it proved to be a huge influence on the MoMA initially with “Modern Architecture” (1932) and “Machine Art” (1934). He gave his museum the task of “fostering an understanding of that which it believes to be the most lively work produced in our time.” He was assisted in this by Philip Johnson – who was head of the Architecture department.

The touchstone for this collaboration is the joint tour of Europe the pair took at the beginning of the “roaring twenties”. In 1927, Barr and Johnson went on the hunt for outstanding architects, not least for their exhibition on building in the modern era. They settled upon Walter Gropius and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, among others. The museum exhibition with the latest works and designs by these two Bauhaus directors was accompanied by Johnson’s epochal book “The International Style”. In connection with rather more theoretical considerations, the two “partners” sought new forms of presentation. After all, Barr at least had a firm aim in mind on the grand tour – the task of fundamentally determining a museum as new.

Illustrating the experiences and events of the fact-finding trip was evidently difficult for the Bielefeld curators. Formulaic wall texts are interspersed with souvenir photos showing views of now legendary exhibition projects around 1930. Presented as a definitive element here is the shared walk through the newly set-up “cabinet of abstracts” in the Provincial Museum in Hanover. Accompanying the photo of this recently restored art space by El Lissitzky, a text appears on the wall in Bielefeld: Johnson’s premise that a modern museum “must give as much importance to installation as to the exhibition itself”.

It was on such hypotheses that MoMA’s “Modern architecture: International Exhibition” was based. Even in the advertising brochure for potential sponsors, Johnson heralds a new type of architecture exhibition, with steel tube furniture and “photography racks” made of glass and metal, and with them the models and large-format photos produced specially for the museum, applied without frames directly to the presentation walls, taking up the whole surface. Preferably designed by Mies van der Rohe himself. In the end though, the result was conventional platforms with antimacassars. And Johnson had to have had these produced and built himself. Not a big difference, but a crucial one nonetheless. However – and this is the crux of this design-historical exhibition – this is not really perceptible in historic photos.

The exhibition, now taken over by the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, attempts to make a virtue of this lack – with the “discovery” of the private residences of Barr and Johnson. Living next door to one another in the same apartment block, the pair had their apartments furnished in a modern style, a three-dimensional Bauhaus manifesto. With his meagre budget, however, the best that family man Barr could hope for was affordable replicas. This was the time when the pioneers not celebrated in Bielefeld – such as Hans Knoll – were just beginning to gather avant-garde designs in order to build up industrial production of these unique pieces. Meanwhile, bachelor Johnson could draw on unlimited resources. He had Bauhaus originals shipped to the USA and brought the director himself over to be his interior architect: “Mies thought so hard about the arrangement of the chairs in a room, in the way that other architects would think about the effect of buildings on a site.”

That may sound, quite literally, “spacey”, but is unfortunately only presented very conventionally: All the furniture is arranged pedantically behind barriers in a row, from the Barcelona chair to the Donald Deskey table through to Marcel Breuer’s B22 etagere. Not a hint of the flair and sense of space of the Bauhaus homes. Here, Johnson was way ahead of his time with his museum “installations”. This exhibition architecture also proved to be so stable that the MoMA could travel, right across the USA, offering presentations in colleges or warehouses. The show “Useful Objects of American Design under 10 $” struck a chord with the public in 1939/40 – and thus became the defining exhibition for economical, functional design in everyday life. It was this that provided inspiration for the Walker Art Center Minneapolis after the Second World War with its “Everyday Art Gallery”, and in 1949 the Detroit Institute of Art with “An Exhibition for Modern Living”.

It was Johnson who kicked it all off, however, with the show “Objects: 1900 and Today”. This was about industrial design, which was now supposed to follow the principles of modern architecture: “machine-like simplicity, smooth surfaces, avoidance of ornamentation”. Inspired by the European tour, by a trend that had caught the attention of the American cultural tourist in 1930 at the Werkbund show in Paris. There, Johnson reported, “German industrial design was far ahead of the rest of the world. Programmatically logical, brilliantly installed, it rose like an island of integrity in a sea of modernistic arbitrariness.”

The formulation “modernistic arbitrariness” nevertheless reveals distance. Then comes the year 1933 when Johnson published his assessment of “Architecture in the Third Reich”. The text is downright misappropriated in Bielefeld. Neither is there any mention of Johnson’s sympathy for the Nazis. Instead, it states merely succinctly, with regard to exhibitions on design, “there was a long delay at the MoMA, because Johnson left the museum in December 1934 to pursue his radical political tendencies”. This occasional separation was hardly surprising, yet Director Barr saw himself confronted with phrases such as: “First Die Neue Sachlichkeit is over. Houses that look like hospitals and factories are taboo. ... Second, architecture will be monumental.”

It was not only towards these aesthetic maxims of the Nazis that Johnson showed himself to be open. When he was forced to advertise for financial support for his exhibition with Bauhaus architects, Johnson confronted his partner Barr with the question: “Mies’s fans are Jews, do we really want them here?”, as Franz Schulze reported in his Johnson biography – relativizing this antisemitism as the view of “an average American upper middle class snob”.

In fact, Johnson arrogantly flaunts elegance and exclusivity in photos. Indeed it is so striking that the question arises, or should arise, of how a dandy like this could be a “Bauhaus pioneer”. Perhaps for Johnson it was about design concepts, against which Hannes Meyer – champion of “Volksbedarf statt Luxusbedarf” (“The need of the people instead of the need of luxury”) – polemicized with the remark that previously in Dessau “unprecedented build-ups were given and from every tea glass a problematic-constructive entity was made”? Or were Barr and Johnson merely small fish following in the wake of a mighty economic flow, that Fordism, which stimulated mass consumption in order to overcome the global economic crisis - including through the “beautified” appearance of consumer goods. This “visual appeal” of a world of goods comprising test tubes, toasters, stainless steel sinks or cash registers is dazzling illuminated in Bielefeld according to the MoMA pattern of “machine art” – with spotlights and glittering glass cabinets. It no longer appears enlightening today, as the historic dimension remains blank: propellers and ball bearings were important articles in the Nazi armory arsenal. “Race scientists” used functionally designed calipers for their skull measurements. This knowledge about things is lost if they are exhibited in all too dignified a way decades later. This type of “installation” casts barely any more light on design and its history. Hence the visitor finds him- or herself at a complete loss standing before the Kunsthalle. The building is actually not – as announced – “the only European museum building by Philip Johnson”. In fact, the architect designed the clunky-brutalist building in 1966 as an archetype according to the monumental model of a German burial mound. The building itself denies – when you look more closely – what is claimed on the façade banner: that a “Bauhaus pioneer” was at work here.

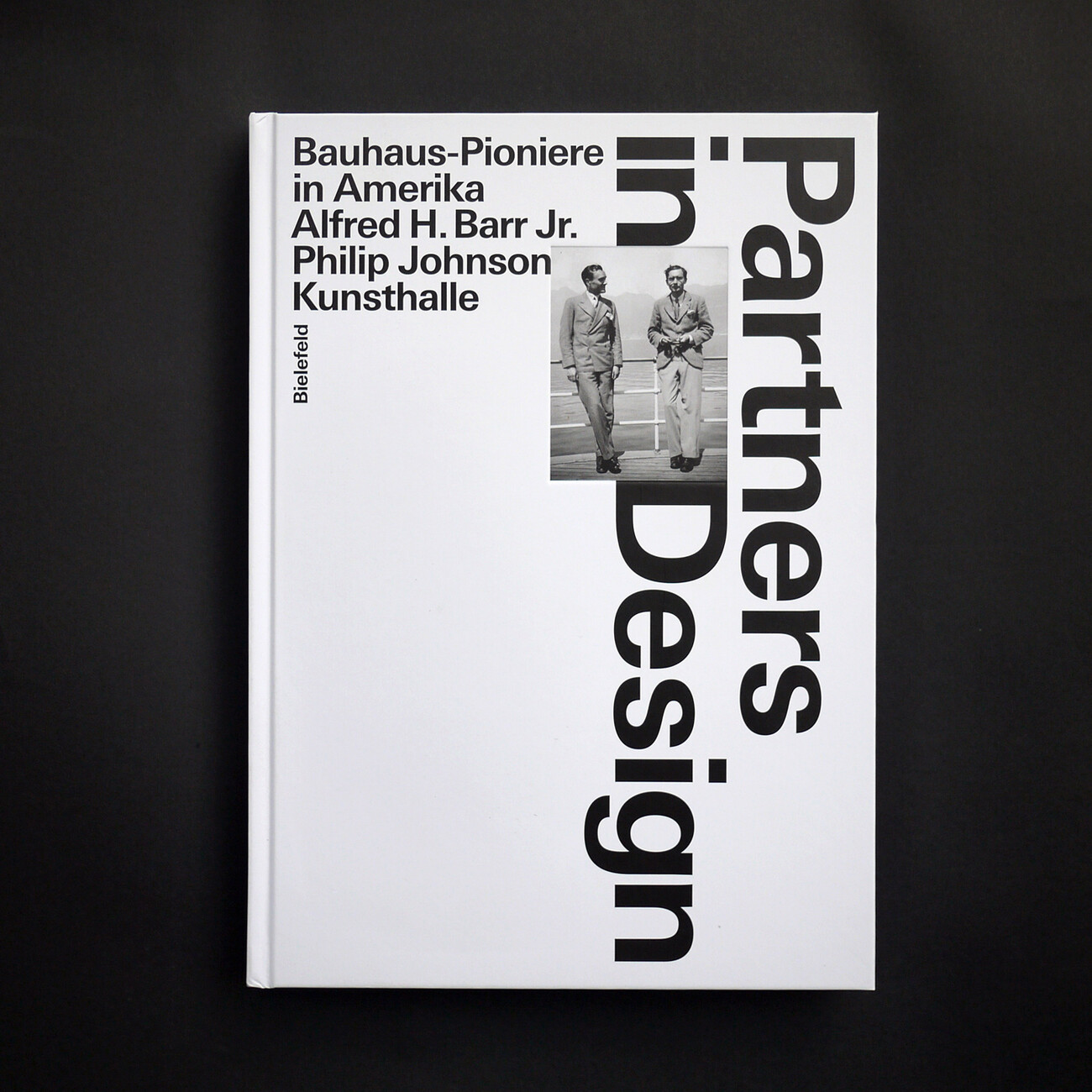

Partners in Design

Alfred H. Barr Jr. und Philip Johnson - Bauhaus-Pioniere in Amerika

Kunsthalle Bielefeld

thru July 23, 2017

Catalog:

Partners in Design

Alfred H. Barr Jr. und Philip Johnson. Bauhaus-Pioniere in Amerika

David A. Hanks/Friedrich Meschede (eds)

240 pp., Hardcover, german, 200 ills.

Arnoldsche Art Publishers, Stuttgart 2017

ISBN 978-3-89790-496-5

38 Euro